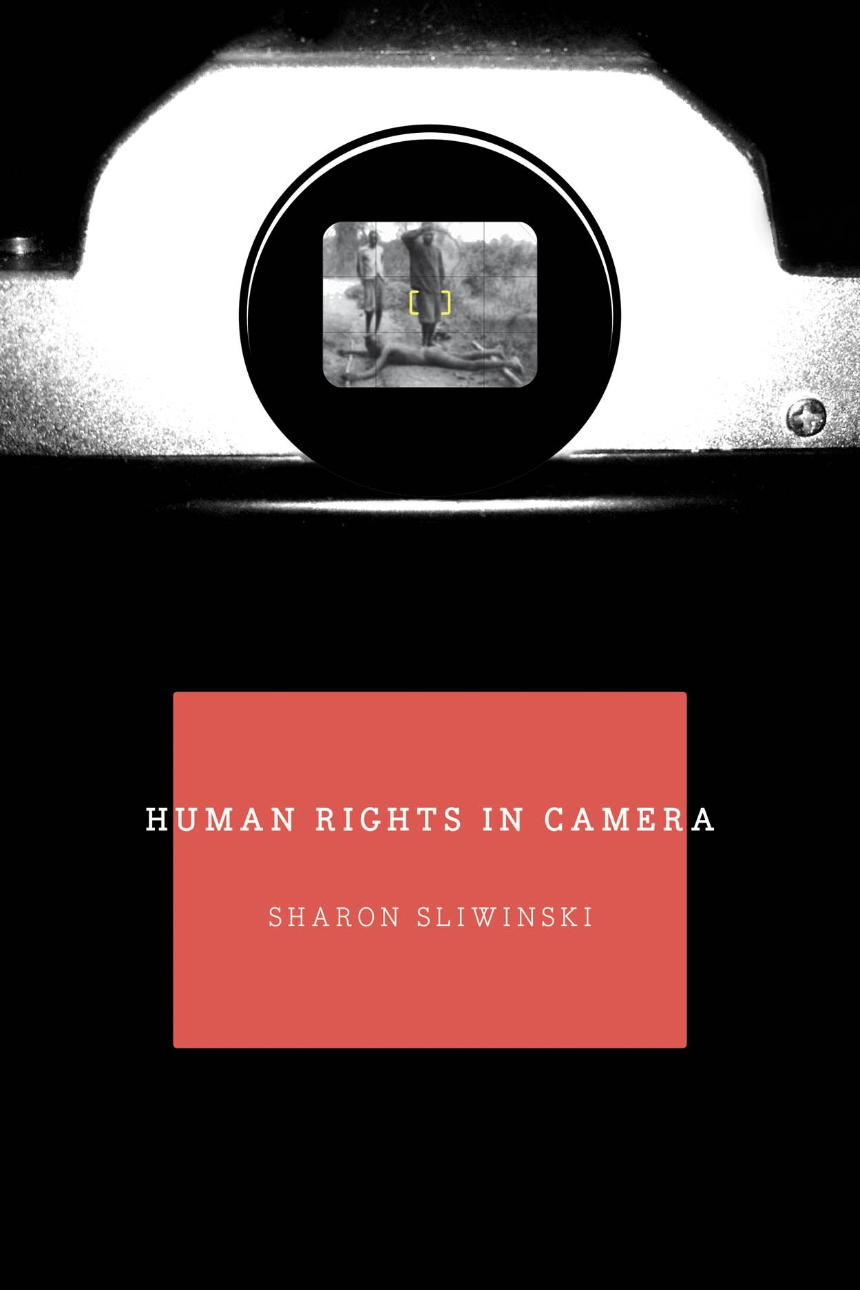

Human Rights In Camera

From the fundamental rights proclaimed in the American and French declarations of independence to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Hannah Arendt’s furious critiques, the definition of what it means to be human has been hotly debated. But the history of human rights—and their abuses—is also a richly illustrated one. Following this picture trail, Human Rights In Camera takes an innovative approach by examining the visual images that have accompanied human rights struggles and the passionate responses people have had to them.

Sharon Sliwinski considers a series of historical events, including the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and the Holocaust, to illustrate that universal human rights have come to be imagined through aesthetic experience. The circulation of images of distant events, she argues, forms a virtual community between spectators and generates a sense of shared humanity. Joining a growing body of scholarship about the cultural forces at work in the construction of human rights, Human Rights In Camera is a novel take on this potent political ideal.

Reviews

Table of Contents

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations Foreword by Lynn Hunt

List of Illustrations Foreword by Lynn Hunt

Introduction

ONE The Spectator of Human Rights

Textual versus pictorial evidence. Following the picture trail opens a view of the spectator of human rights whose task is to judge. Hannah Arendt’s return to Kant on the distinction between moral and aesthetic judgments. Adolph Eichmann exposes the frailty of judgment. Critiques of the spectator. Lyotard’s emphasis on dissensus in the sensus communis. The scene of human rights as a scene of aesthetic conflict.

Textual versus pictorial evidence. Following the picture trail opens a view of the spectator of human rights whose task is to judge. Hannah Arendt’s return to Kant on the distinction between moral and aesthetic judgments. Adolph Eichmann exposes the frailty of judgment. Critiques of the spectator. Lyotard’s emphasis on dissensus in the sensus communis. The scene of human rights as a scene of aesthetic conflict.

TWO Humanity from the Ruins: 1755

November 1, 1755: a beautiful and clear day . . . The Lisbon earthquake as the first international mass media event. “Truthful” versus “fantastical” representations. The sublime quaking of a worldview and the emergence of a notion of a common humanity. The quake frames later responses to atrocity. The Disasters of War. Goya’s judgment: “They do not want to.” Print pedagogy for the spectator of human rights.

THREE The Kodak on the Congo: 1904

The first use of “crimes against humanity.” King Leopold’s atrocities in the Congo Free State. Early humanitarian responses. The intervention of the photograph. The phantasmagoric appeals of the Congo Reform Association. Dreaming of human rights. The first international human rights movement ends with a whimper.

FOUR Rolleiflex Witness: 1945

Before there was the idea of the Holocaust, there were the pictures. Photographic evidence becomes the standard for claims of atrocity. Lee Miller’s reports for Vogue. The Dachau Death Train: images bear the mark of this horror. Testimony visualis, or, communication without understanding. Dignity and the “abstract nakedness” of being nothing but human. The “philosophically absurd” claims of the Universal Declaration. The time of our singing: political hymns of belonging.

FIVE Genocide, Again: 1992

Genocide as “an exercise in community building.” Lemkin’s linguistic invention and the legislation of international law. Yet neither visibility nor legibility could prevent the reoccurrence of this phenomenon. Yugoslavia: the first televised genocide. The barometer rises in Rwanda. A catalogue of breakdowns. Toward an ethics of failure.

Coda

Acknowledgment Notes Index