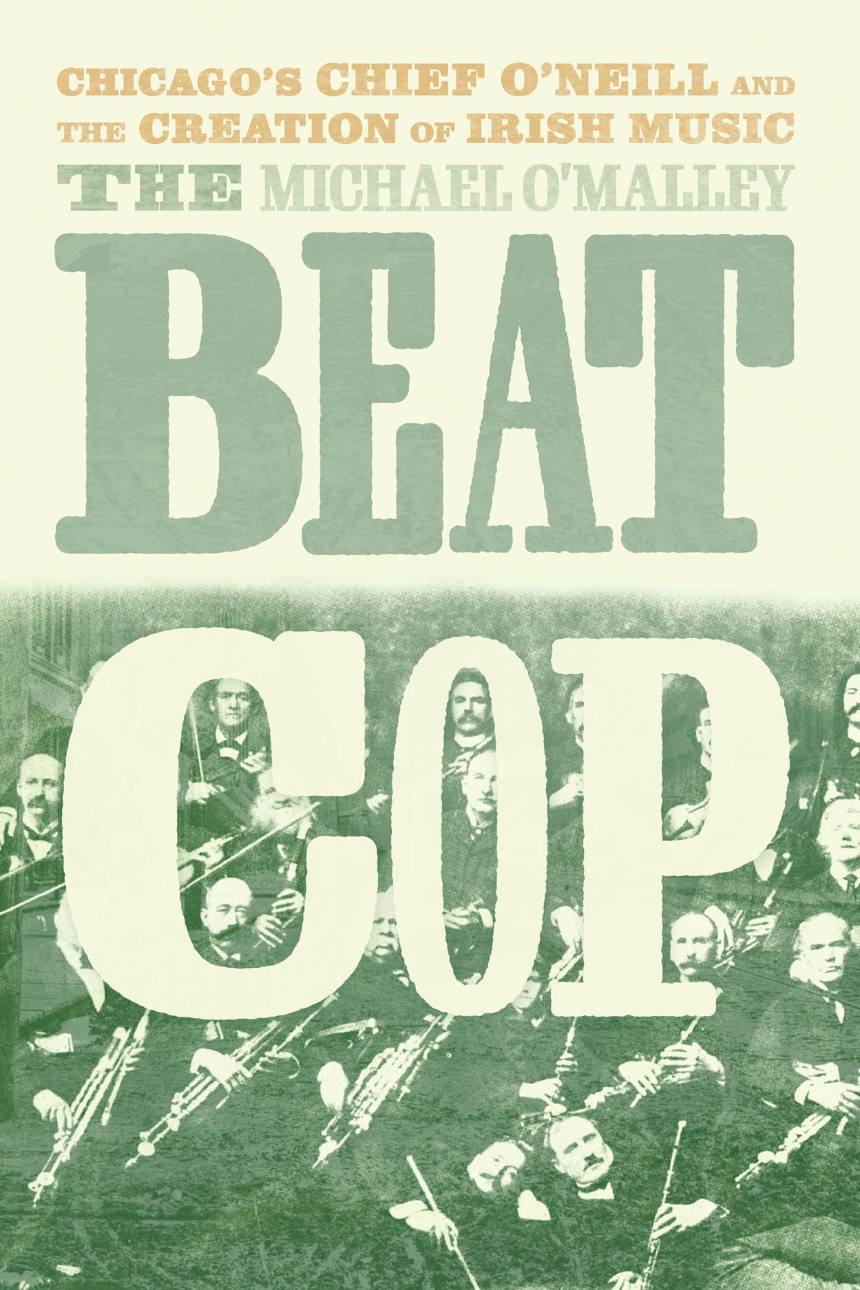

The Beat Cop

Chicago’s Chief O’Neill and the Creation of Irish Music

The remarkable story of how modern Irish music was shaped and spread through the brash efforts of a Chicago police chief.

Irish music as we know it today was invented not just in the cobbled lanes of Dublin or the green fields of County Kerry, but also in the burgeoning metropolis of early-twentieth-century Chicago. The genre’s history combines a long folk tradition with the curatorial quirks of a single person: Francis O’Neill, a larger-than-life Chicago police chief and an Irish immigrant with a fervent interest in his home country’s music.

Michael O’Malley’s The Beat Cop tells the story of this singular figure, from his birth in Ireland in 1865 to his rough-and-tumble early life in the United States. By 1901, O’Neill had worked his way up to become Chicago’s chief of police, where he developed new methods of tracking criminals and recording their identities. At the same time, he also obsessively tracked and recorded the music he heard from local Irish immigrants, enforcing a strict view of what he felt was and wasn’t authentic. Chief O’Neill’s police work and his musical work were flip sides of the same coin, and O’Malley delves deep into how this brash immigrant harnessed his connections and policing skills to become the foremost shaper of how Americans see, and hear, the music of Ireland.

Reviews

Table of Contents

1 Tralibane Bridge: Childhood and Memory

2 Out on the Ocean: O’Neill’s Life at Sea, in Port, and in the Sierra

3 Rolling on the Ryegrass: A Year on the Missouri Prairie

4 The New Policeman: O’Neill’s Rise through the Ranks

5 Rakish Paddy: The Chicago Irish and Their World

6 Chief O’Neill’s Favorite: The Chief in Office

7 King of the Pipers: O’Neill’s Work in Retirement

Epilogue Happy to Meet, Sorry to Part: The Legacy

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Excerpt

In rare quiet moments at Harrison Street O’Neill liked to work out a few tunes on the flute. O’Neill was “music mad,” obsessed with Irish dance music. He had heard it growing up in Ireland, at rural dances; or late at night through stone walls when parties continued after his parents sent him to bed. In Chicago he heard tunes all the time: tunes with no name or many names; tunes that sounded hauntingly familiar; tunes that mixed parts of other tunes, all circulating among the more than 300,000 Irish immigrants who worked, went to church, sinned, and got arrested so their friends could cajole O’Neill into letting them go. The disorder bothered him. He picked up the flute and started to play a phrase. “Captain,” someone called, “phone call for you out front.” He set his flute down on the table, among the opium pipes, and walked away to take the call.

While he was away at the phone a policeman, or perhaps an alderman or a lawyer or a magistrate or a reporter— some Harrison Street “regular”— walked by and stole some pipes off the table. Opium pipes had lately become a fashionable exotic decoration among the city’s elite, a “crazy fad.” “Always after a raid we can look for calls from the women who want pipes to decorate the parlor,” a police captain told the reporter: “Wives and daughters of millionaires have frequently been here begging for pipes.” The thief had promised to get one for a wealthy Michigan Avenue woman: he would do her a favor, and she would surely do one for him. A keyless wooden flute or a tin whistle could look a lot like an opium pipe to a man in a hurry, and when O’Neill returned several pipes and his flute had vanished. The next day the flute magically reappeared, with no explanation.

The story, printed in the Chicago Inter Ocean, has so much of Chicago to it that it might even be true. Th e people doing “favors” for “friends,” the sordid vice district, but also the upper- class women’s enthusiasm for the exotic artifacts of vice. No matter how much shuddering public distaste people expressed, vice districts went on, generating revenue for the elected alderman who used the revenue to persuade voters or generate extra cash for police and the law.

Calls for reform never ceased, but Chicago reformers often ended up behaving no better than the people they aimed to reform. The journalist Lincoln Steffens praised the Municipal Voters League, a group of reformers trying to “clean up” the city in O’Neill’s day, including a young lawyer named Hoyt King. In his zeal, King later hired private detectives to “get something” on O’Neill, telling his agents to spare no effort: “there’s unlimited money behind it.” A letter to O’Neill warned him that King “would not hesitate to have you assassinated if he could down you by no other means.” King represented the reform party, the vendors of high-minded rhetoric. No wonder Captain O’Neill turned his mind to the music of his youth.

Francis O’Neill, from Tralibane near Bantry, in County Cork, left Ireland in 1865 at seventeen years old. He spent four years as an itinerant sailor, circling the globe; he was shipwrecked on a barren Pacific island and nearly starved; he herded sheep in the Sierra Nevada foothills, sleeping under the stars for five months. He taught school for a year in rural Missouri and spent a summer working ships on the Great Lakes. Settled in Chicago by 1871, he labored in meatpacking houses, lumber mills, and freight yards. When he found his advancement blocked, he joined the police. A thief shot him in his first month on duty, but he survived and through talent, hard work, patronage connections, and favors from friends he rose to general superintendent of the Chicago police, the “Chief,” by 1901. He worked during the Haymarket bombing and the Columbian Exposition; during the Pullman strike he slept at the station house for weeks and daily confronted rioting crowds. The anarchist Emma Goldman praised his courtesy and intelligence. He navigated saloons and backroom politics; he got into a street brawl with a notoriously thuggish alderman that put him on the front pages; and he pulled bodies from the wreckage of the Iroquois theater fire, which killed 600 people. Late in his police career, and in a very comfortable retirement, he published a series of books on Irish music. These books made him a hero in Ireland; he preserved a heritage that might otherwise have vanished, and a memorial statue now stands near his birthplace. A Chief O’Neill’s pub graces Chicago, and for decades Irish immigrant flute player Kevin Henry played an annual concert in the doorway of O’Neill’s tomb, to honor “the man that saved our heritage.”

This story tells about adventure, intrigue, and momentous events, but also about colonialism and what it does to people. Born an Irish colonial subject of Queen Victoria, O’Neill learned in the “National Schools” to see himself as a “happy English child.” The smart, bookish boy fled that colonial status for the sea and later escaped it altogether when he took the oath of citizenship to the US in 1873.

But then a different kind of colonization took place, colonization by industrial life and the multitude of new ideas and technologies it offered. O’Neill patrolled Chicago as an agent of the state, part of the apparatus that organized and administered the city. He allied himself with the city’s business class, not the Irishmen and women on strike. From his office in city hall he then used techniques of the modern police force to map and colonize Irish music.

The two things— police work and music collection— might seem at first to have nothing in common. In uniform he battled with criminals and broke up crowds of strikers; as a music collector he met ordinary people in homes, theaters, and on the streets and memorized their folk music. But as he rose in police ranks he also tracked suspects and sorted their identities; he photographed them, measured them, and filed cross-referenced records. As chief of police in a city of 2 million people he testified at hearings, managed personnel, oversaw budgets, and wrangled statistics into annual reports. As a music collector he tracked down fugitive tunes and assessed their identity, compared them to thousands of other tunes, established their backstories, sorted the impostor from the genuine, and then formally organized them by type. His police work and his musical work were flip sides of the same coin, part of new ways of thinking about community, part of the administrative and management techniques of modern industrial society.