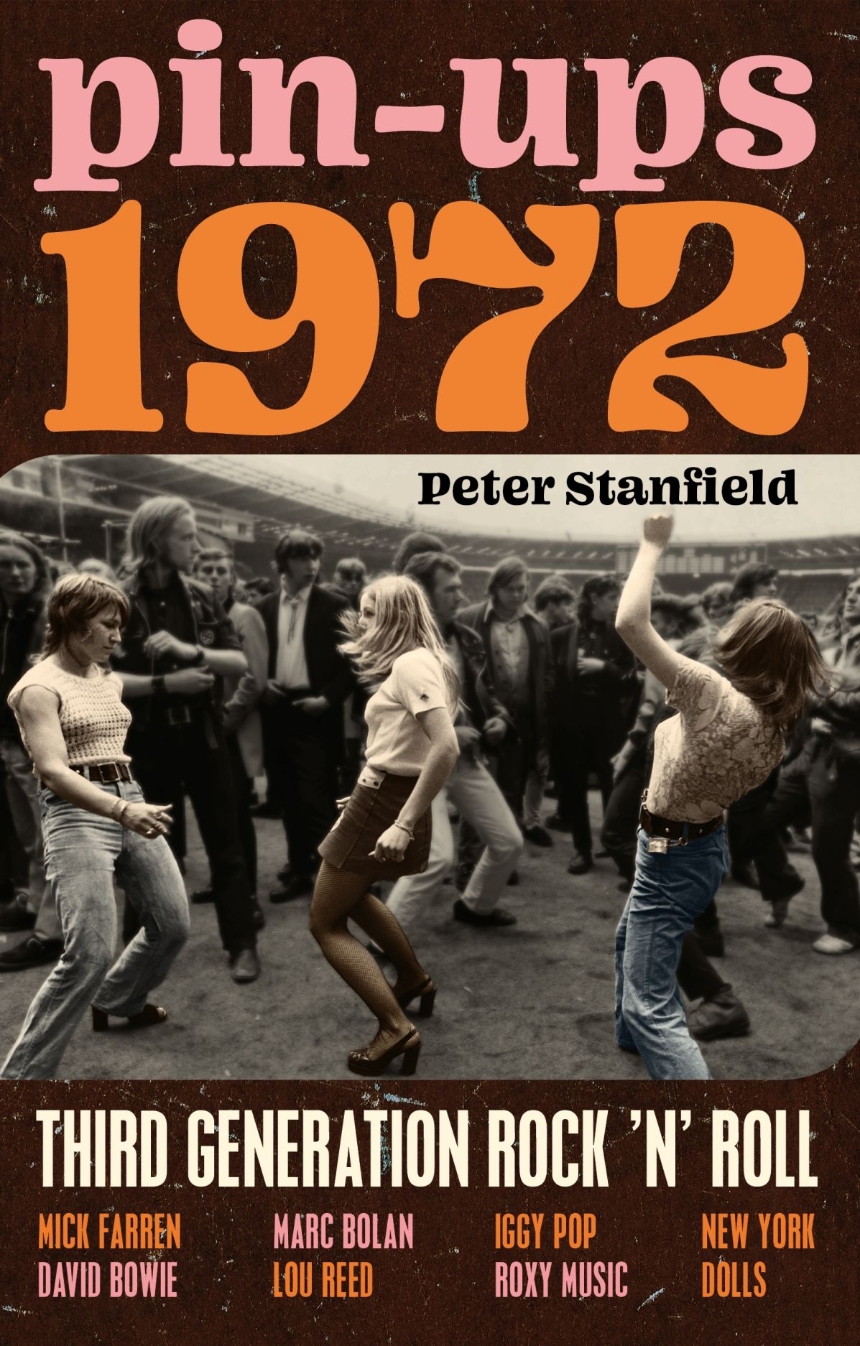

A sleazy, neon- and grease-stuffed chronicle of London’s rock scene during the pivotal year of 1972—from Marc Bolan to the New York Dolls.

Elvis, Eddie, Chuck, Gene, Buddy, and Little Richard were the original rockers. Dylan, the Beatles, the Stones, and the Who formed rock’s second coming. As the 1960s turned into the 1970s, the crucial question was who would lead rock ’n’ roll’s third generation?

Pin-Ups 1972 tracks the London music scene during this pivotal year, all Soho sleaze, neon, grease, and leather. It begins with the dissolution of the underground and the chart success of Marc Bolan. T. Rextasy formed the backdrop to Lou Reed and Iggy Pop’s British exile and their collaborations with David Bowie. This was the year Bowie became a star and redefined the teenage wasteland. In his wake followed Roxy Music and the New York Dolls, future-tense rock ’n’ roll revivalists. Bowie, Bolan, Iggy, Lou, Roxy, and the Dolls—pin-ups for a new generation.

Elvis, Eddie, Chuck, Gene, Buddy, and Little Richard were the original rockers. Dylan, the Beatles, the Stones, and the Who formed rock’s second coming. As the 1960s turned into the 1970s, the crucial question was who would lead rock ’n’ roll’s third generation?

Pin-Ups 1972 tracks the London music scene during this pivotal year, all Soho sleaze, neon, grease, and leather. It begins with the dissolution of the underground and the chart success of Marc Bolan. T. Rextasy formed the backdrop to Lou Reed and Iggy Pop’s British exile and their collaborations with David Bowie. This was the year Bowie became a star and redefined the teenage wasteland. In his wake followed Roxy Music and the New York Dolls, future-tense rock ’n’ roll revivalists. Bowie, Bolan, Iggy, Lou, Roxy, and the Dolls—pin-ups for a new generation.

Reviews

Excerpt

INTRODUCTION: FIRST IS FIRST, SECOND IS BEST AND THE THIRD GENERATION IS NOWHERE

That’s how fast pop is: the anarchists of one year are the boring old farts of the next.—Nik Cohn, Pop from the Beginning (1969)

This is a book about the rock acts that became the pin-ups of 1972, that year’s anarchists. To tell their stories, Pin-Ups 1972 pivots around a commonplace catchphrase in early 1970s pop criticism: ‘third-generation rock ’n’ roll’. The term was introduced to London’s rock cognoscenti by Alice Cooper on a promotional visit to England in 1971; he said his band and The Stooges were third-generation rock’s best representatives. It was likely he intended it to be no more than a pithy aphorism to differentiate his and Iggy’s band from the competition, to signal that they were the next in line, but the idea behind the phrase found a receptive audience among those who wrote for Britain’s Underground press. They ran with the concept, putting it into wider circulation, and turned it into a refrain that became a summary definition for rock’s current predicament, namely: if The Beatles followed Elvis, and they were now sundered, who was their heir apparent? The need to find an answer was motivated by the fear that the scene was fast burning out, smothered by conformity to the demands of the marketplace. The heat once generated by rock’s seditious intent was turning to cold ash. Who then might fan the dying embers and put some fire back into rock ’n’ roll? For rock journalists, aesthetes and muckrakers alike, their role was to act as the accelerant for the conflagration they ardently hoped was to follow.

The first-generation were the original rockers: Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran. The second-generation were those who were directly and immediately inspired by these innovators: The Beatles, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Who. But where it was easy to see the break between first and second iterations, the end of the second cycle and the start of the third was less obvious.

It was widely accepted that things had fallen apart when Elvis joined the army, Little Richard got religion, Chuck went to jail and Buddy and Eddie were killed. Following the wake, the vanguard of the resurrection shuffle was never in doubt. The contention in 1970–72 was over whether or not the succeeding generation had now reached its end point. All who cared about such things could agree that something had changed with the break-up of The Beatles, with Altamont, the Tate–LaBianca murders and the deaths of Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Brian Jones and Jim Morrison between 1969 and 1971. Whatever its end-of-days symbolism, the difficulty with this particular cut-off point was where it left those rockers, such as the Rolling Stones and The Who, who were still active and creatively valid, never mind figures such as Bowie and Bolan, who had roots deep into the second-generation, even as they themselves were seen as defining actors in the third.

As the 1960s rolled into the ’70s and Dylan, Lennon and Jagger edged into their thirties, the truism that rock was about the now, the new and the immediate, that it was fundamentally teenage in orientation, needed to be reassessed. How was the discrepancy between the ideal and the reality, between youth and maturity to be managed? Some ignored the question, their taste confirmed by displays of virtuosity and grandiose concepts measured against the fickle values of the teen pop consumer. Others, greaser revivalists, smothered the question under a shroud of nostalgia for the prelapsarian 1950s. A third camp dealt with it by redefining the canon to better classify just what rock was so that its latest iteration could be named and fêted. Pin-Ups 1972 is about this last group.

***

Iconoclasm would play a key role in helping to define the generational shift. Nik Cohn’s earlier and somewhat unique pursuit of the contrary in pop criticism was a model of sorts: few others at the time, or since, have proselytized with such passion and conviction for an outlier while showing an equal measure of disdain for the masters of the idiom, P. J. Proby and Bob Dylan respectively in his case. With the new cohort of rock writers– Ian MacDonald, Charles Shaar Murray, Duncan Fallowell, Roy Hollingworth and Nick Kent among them – the cultivation of a discriminating sensitivity, in which an amplification of cultish preferences underlay critical evaluations, becamethe norm. Dylan, The Beatles, the Stones and The Who stopped being the markers against whom all might be judged. They were, for the most part, beyond contention, with the gods so to speak. In their earthly place, the process of canonizing the Velvet Underground and The Stooges, who occupied the hinterland between the second and third generations, took hold.

Running in parallel with a critic’s show of discerning taste was an archivist’s pursuit of the arcane pleasures found in the juvenile delirium of punk bands from the first psychedelic era, the high-school drama of girl groups, and the delinquent rhythms of rockabilly. Such forms represented paradise lost, but as guides they might yet point to the Promised Land. In becoming a pretender’s champion, the critic linked them to such predecessors and explained how they held true to rock ’n’ roll’s core values as embodied in Shadows of Knight, The Ronettes, Charlie Feathers. Through showing a connoisseur’s appreciation for the finer points of rock’s chequered history, critics set out their bona fides when it came to revealing the new challengers, as with Hollingworth and the New York Dolls, Richard Williams and Roxy Music, Fallowell and Krautrock, and MacDonald, Murray and Simon Frith, in a rather more congested field, with Bowie. In near splendid isolation, Kent chose to occupy the teenage wasteland with Iggy and the Stooges.

Rock’s three generations are partitioned and examined in Nik Cohn’s and Guy Peellaert’s illustrated volume from 1973, Rock Dreams, which begins with the idea of rock and roll as a ‘secret society, an enclosed teen fantasy’ and as an obsession. The authors track the cycles of rock, how visions of it changed, became more complex and diversified, ‘and the ways in which they remained always the same . . . Its ever-changing, never-changing rituals.’ In a key image, Elvis sits at the centre of a table. In front of him is a last supper of cokes and burgers, and surrounding him are his twelve disciples (of a decidedly British bias) – Vince Taylor, Tommy Steele, P. J. Proby, Billy Fury, Tommy Sands, Rick Nelson, Tom Jones, Eddie Cochran, Terry Dene, Ritchie Valens, Fabian and Cliff Richard. Like Jesus, Elvis is a figure big enough to contain multitudes. In other images, he is a street punk loitering outside a poolhall, a devout Christian and a married man. Those who followed his lead are mono-dimensional versions of one or other of these aspects. In a British pub surrounded by rockers with greasy quiffs and leather jackets, Gene Vincent threatens a police detective with a flick knife; homely Eddie Cochran hangs out at the ice cream parlour waiting for the right girl to drift by and save him from his summertime blues; and the Everly Brothers make out with their girlfriends, wives to be, at the drive-in.

The first generation of rockers are followed in Cohn’s tale by Dylan and the British Invasion, an era that lasted until around 1968 when rock, he writes, got complicated. It could no longer be ‘contained in a single direction, one overall fantasy, and it broke apart into different factions and schools . . .From now on, all was chaos; sometimes hopeless and sometimes splendid confusion.’ What was left was a mess, populated by serious musicians, poets and bogeymen. Some looked to the future, others to the past; some mixed things up with Country and Western, others with Jazz, or the pseudo-Classical and mock-Oriental. The effect was that rock had ‘grown self-important, predictable, flat’. The kinship between performer and audience had vanished. Solemnity, jadedness and exhaustion followed. Decadent rot had set in, and the moment of rock had passed:

it will be David Bowie (linked with Lou Reed in Peellaert’s illustration) who best helped define the fallout after the legacy of the second-generation had been squandered.

That’s how fast pop is: the anarchists of one year are the boring old farts of the next.—Nik Cohn, Pop from the Beginning (1969)

This is a book about the rock acts that became the pin-ups of 1972, that year’s anarchists. To tell their stories, Pin-Ups 1972 pivots around a commonplace catchphrase in early 1970s pop criticism: ‘third-generation rock ’n’ roll’. The term was introduced to London’s rock cognoscenti by Alice Cooper on a promotional visit to England in 1971; he said his band and The Stooges were third-generation rock’s best representatives. It was likely he intended it to be no more than a pithy aphorism to differentiate his and Iggy’s band from the competition, to signal that they were the next in line, but the idea behind the phrase found a receptive audience among those who wrote for Britain’s Underground press. They ran with the concept, putting it into wider circulation, and turned it into a refrain that became a summary definition for rock’s current predicament, namely: if The Beatles followed Elvis, and they were now sundered, who was their heir apparent? The need to find an answer was motivated by the fear that the scene was fast burning out, smothered by conformity to the demands of the marketplace. The heat once generated by rock’s seditious intent was turning to cold ash. Who then might fan the dying embers and put some fire back into rock ’n’ roll? For rock journalists, aesthetes and muckrakers alike, their role was to act as the accelerant for the conflagration they ardently hoped was to follow.

The first-generation were the original rockers: Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran. The second-generation were those who were directly and immediately inspired by these innovators: The Beatles, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Who. But where it was easy to see the break between first and second iterations, the end of the second cycle and the start of the third was less obvious.

It was widely accepted that things had fallen apart when Elvis joined the army, Little Richard got religion, Chuck went to jail and Buddy and Eddie were killed. Following the wake, the vanguard of the resurrection shuffle was never in doubt. The contention in 1970–72 was over whether or not the succeeding generation had now reached its end point. All who cared about such things could agree that something had changed with the break-up of The Beatles, with Altamont, the Tate–LaBianca murders and the deaths of Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Brian Jones and Jim Morrison between 1969 and 1971. Whatever its end-of-days symbolism, the difficulty with this particular cut-off point was where it left those rockers, such as the Rolling Stones and The Who, who were still active and creatively valid, never mind figures such as Bowie and Bolan, who had roots deep into the second-generation, even as they themselves were seen as defining actors in the third.

As the 1960s rolled into the ’70s and Dylan, Lennon and Jagger edged into their thirties, the truism that rock was about the now, the new and the immediate, that it was fundamentally teenage in orientation, needed to be reassessed. How was the discrepancy between the ideal and the reality, between youth and maturity to be managed? Some ignored the question, their taste confirmed by displays of virtuosity and grandiose concepts measured against the fickle values of the teen pop consumer. Others, greaser revivalists, smothered the question under a shroud of nostalgia for the prelapsarian 1950s. A third camp dealt with it by redefining the canon to better classify just what rock was so that its latest iteration could be named and fêted. Pin-Ups 1972 is about this last group.

***

Iconoclasm would play a key role in helping to define the generational shift. Nik Cohn’s earlier and somewhat unique pursuit of the contrary in pop criticism was a model of sorts: few others at the time, or since, have proselytized with such passion and conviction for an outlier while showing an equal measure of disdain for the masters of the idiom, P. J. Proby and Bob Dylan respectively in his case. With the new cohort of rock writers– Ian MacDonald, Charles Shaar Murray, Duncan Fallowell, Roy Hollingworth and Nick Kent among them – the cultivation of a discriminating sensitivity, in which an amplification of cultish preferences underlay critical evaluations, becamethe norm. Dylan, The Beatles, the Stones and The Who stopped being the markers against whom all might be judged. They were, for the most part, beyond contention, with the gods so to speak. In their earthly place, the process of canonizing the Velvet Underground and The Stooges, who occupied the hinterland between the second and third generations, took hold.

Running in parallel with a critic’s show of discerning taste was an archivist’s pursuit of the arcane pleasures found in the juvenile delirium of punk bands from the first psychedelic era, the high-school drama of girl groups, and the delinquent rhythms of rockabilly. Such forms represented paradise lost, but as guides they might yet point to the Promised Land. In becoming a pretender’s champion, the critic linked them to such predecessors and explained how they held true to rock ’n’ roll’s core values as embodied in Shadows of Knight, The Ronettes, Charlie Feathers. Through showing a connoisseur’s appreciation for the finer points of rock’s chequered history, critics set out their bona fides when it came to revealing the new challengers, as with Hollingworth and the New York Dolls, Richard Williams and Roxy Music, Fallowell and Krautrock, and MacDonald, Murray and Simon Frith, in a rather more congested field, with Bowie. In near splendid isolation, Kent chose to occupy the teenage wasteland with Iggy and the Stooges.

Rock’s three generations are partitioned and examined in Nik Cohn’s and Guy Peellaert’s illustrated volume from 1973, Rock Dreams, which begins with the idea of rock and roll as a ‘secret society, an enclosed teen fantasy’ and as an obsession. The authors track the cycles of rock, how visions of it changed, became more complex and diversified, ‘and the ways in which they remained always the same . . . Its ever-changing, never-changing rituals.’ In a key image, Elvis sits at the centre of a table. In front of him is a last supper of cokes and burgers, and surrounding him are his twelve disciples (of a decidedly British bias) – Vince Taylor, Tommy Steele, P. J. Proby, Billy Fury, Tommy Sands, Rick Nelson, Tom Jones, Eddie Cochran, Terry Dene, Ritchie Valens, Fabian and Cliff Richard. Like Jesus, Elvis is a figure big enough to contain multitudes. In other images, he is a street punk loitering outside a poolhall, a devout Christian and a married man. Those who followed his lead are mono-dimensional versions of one or other of these aspects. In a British pub surrounded by rockers with greasy quiffs and leather jackets, Gene Vincent threatens a police detective with a flick knife; homely Eddie Cochran hangs out at the ice cream parlour waiting for the right girl to drift by and save him from his summertime blues; and the Everly Brothers make out with their girlfriends, wives to be, at the drive-in.

The first generation of rockers are followed in Cohn’s tale by Dylan and the British Invasion, an era that lasted until around 1968 when rock, he writes, got complicated. It could no longer be ‘contained in a single direction, one overall fantasy, and it broke apart into different factions and schools . . .From now on, all was chaos; sometimes hopeless and sometimes splendid confusion.’ What was left was a mess, populated by serious musicians, poets and bogeymen. Some looked to the future, others to the past; some mixed things up with Country and Western, others with Jazz, or the pseudo-Classical and mock-Oriental. The effect was that rock had ‘grown self-important, predictable, flat’. The kinship between performer and audience had vanished. Solemnity, jadedness and exhaustion followed. Decadent rot had set in, and the moment of rock had passed:

Real energy survived only in pockets, where scattered groups or individuals refused to be sucked under by the general smog and, steering clear of movements, fads, classifications, quietly went their own way. The Rock dreams that remained were bred in isolation: private visions, personal obsessions.

Marc Bolan and Rod Stewart are among those that slip out of the amorphous crowd to become guarded passions, butit will be David Bowie (linked with Lou Reed in Peellaert’s illustration) who best helped define the fallout after the legacy of the second-generation had been squandered.