An illuminating investigation into the interdisciplinary impact of the beloved modern classical composer.

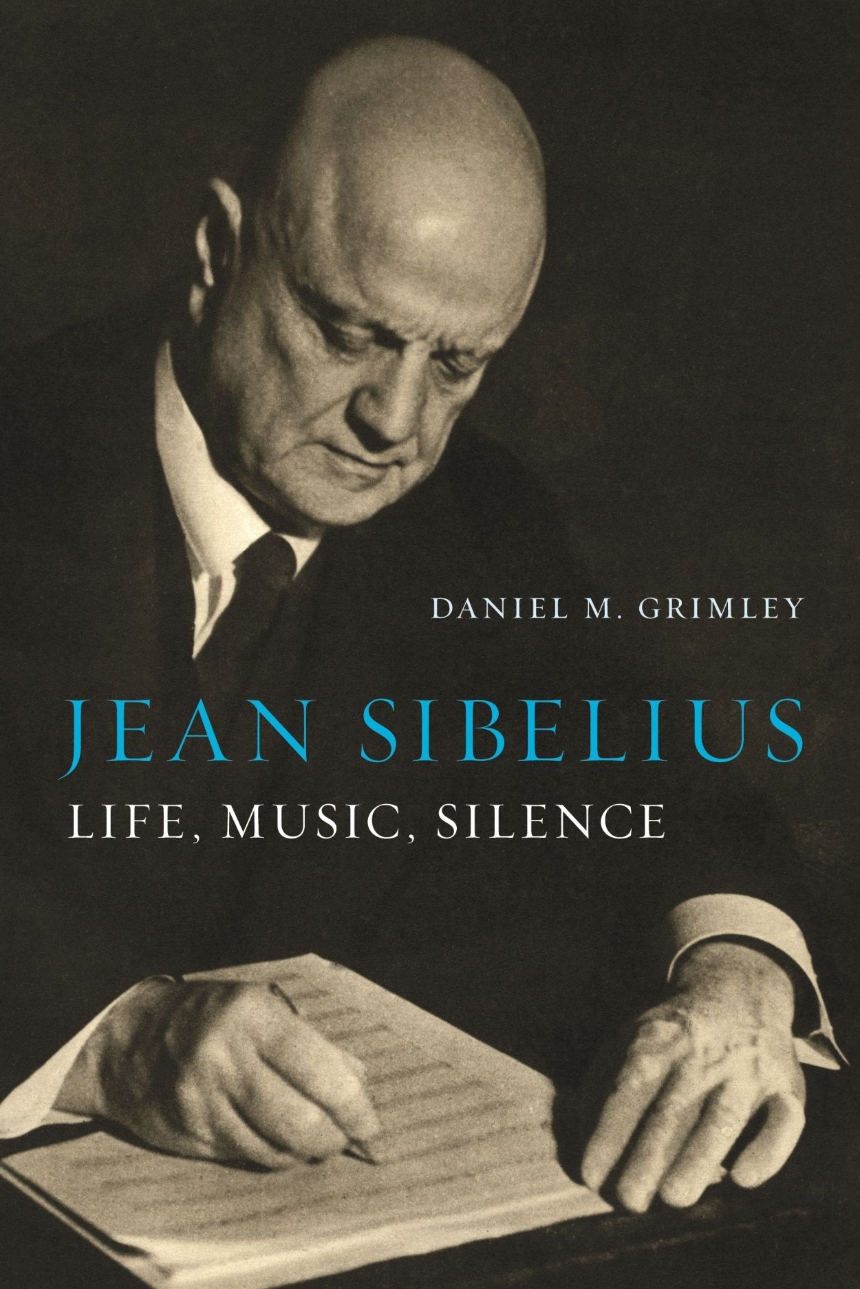

Few composers have enjoyed such critical acclaim—or longevity—as Jean Sibelius, who died in 1957 aged ninety-one. Always more than simply a Finnish national figure, an “apparition from the woods” as he ironically described himself, Sibelius’s life spanned turbulent and tumultuous events, and his work is central to the story of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century music. This book situates Sibelius within a rich interdisciplinary environment, paying attention to his relationship with architecture, literature, politics, and the visual arts. Drawing on the latest developments in Sibelius research, it is intended as an accessible and rewarding introduction for the general reader, and it also offers a fresh and provocative interpretation for those more familiar with his music.

Few composers have enjoyed such critical acclaim—or longevity—as Jean Sibelius, who died in 1957 aged ninety-one. Always more than simply a Finnish national figure, an “apparition from the woods” as he ironically described himself, Sibelius’s life spanned turbulent and tumultuous events, and his work is central to the story of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century music. This book situates Sibelius within a rich interdisciplinary environment, paying attention to his relationship with architecture, literature, politics, and the visual arts. Drawing on the latest developments in Sibelius research, it is intended as an accessible and rewarding introduction for the general reader, and it also offers a fresh and provocative interpretation for those more familiar with his music.

Reviews

Excerpt

Sibelius was obsessed by questions of social distinction. As a Swedish-speaking Finn, he always felt as though he was in a minority, and his middle-class provincial background brought its own set of standards and obligations. ‘You are too aristocratic for our socialist times,’ he once remarked to himself,5 and for much of his life he believed that he was descended from an ancient Swedish family line. At times, this brought him into conflict with his country’s fledgling aims and aspirations. In a newspaper interview in 1910, the poet Eino Leino, for example, stated: ‘we have two cultures and nations, one Finnish, the other Swedish, which are moving fast apart.’6 As Sibelius acutely realized, music might deepen those divisions, or it could bring the nation together. Music-making had always been an intrinsic part of his childhood domestic routine. After the early death of his father, who passed away when he was barely two years old, Sibelius’s close correspondence, especially with his uncle Pehr, recorded his unusually sensitive responses to the sounds of the garrison town of his youth and the countryside beyond. Indeed, Sibelius’s immersive imagination was swiftly attuned to the way in which aspects of the modern world – the railway, industry and commerce – were beginning to encroach upon life in the Finnish regions. He was initially sent to study law at Helsinki University but dropped out of his course within a year and enrolled at the Helsinki Music Institute (later renamed the Sibelius Academy), founded by Martin Wegelius in 1882. Here, Sibelius’s colleagues included the Italian pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni, who became a close friend and who shared many of Sibelius’s aesthetic concerns and preoccupations. Sibelius was also deeply inspired by Robert Kajanus, a Wagnerian composer and conductor who was one of the most dynamic figures in late nineteenth-century Finnish life. It was nevertheless Sibelius’s postgraduate study abroad – first with Albert Becker in Berlin and later with Karl Goldmark in Vienna – that really widened his artistic horizons, and which led to his first major musical success: the premiere of his Kullervo Symphony in 1892. From the very outset, then, Sibelius’s career was marked by an irresolvable tension: the creative stimulus provided by his encounter with an international music scene versus the catalyzing influence of material drawn from a more local source (whether the Kalevala or the Finnish landscape).

Sibelius’s interest in the Finnish language and its vernacular cultures was stimulated partly by the increasingly desperate political situation in which Finland found itself in the 1890s: the final years of the century saw increasingly hardline crackdowns on separatist activity. But it was also circumstantial. His wife, Aino, was a member of one of Finland’s elite nationalist families, the Järnefelts, and an ardent proponent of the Finnish cause. She was always, in that sense, more politically connected and engaged than her husband. Sibelius’s letters in their early correspondence, recently published, slips continually between Finnish and Swedish (the language in which he still felt most comfortable). Association with the Järnefelt circle also brought him into close contact with a group of artists, writers and intellectuals, including the painter Akseli GallenKallela, who turned to Finnish folk materials (mythology, landscape and design) as a rich and fertile creative resource. Sibelius found himself, whether by design or accident, to be a key player in demands for an independent Finnish voice. But he swiftly realized that the nationalist route was itself a creatively limiting one, and he increasingly sought to present himself as an artist working on the broader international stage: a strategic decision that brought its own defeats and rewards.

Sibelius’s interest in the Finnish language and its vernacular cultures was stimulated partly by the increasingly desperate political situation in which Finland found itself in the 1890s: the final years of the century saw increasingly hardline crackdowns on separatist activity. But it was also circumstantial. His wife, Aino, was a member of one of Finland’s elite nationalist families, the Järnefelts, and an ardent proponent of the Finnish cause. She was always, in that sense, more politically connected and engaged than her husband. Sibelius’s letters in their early correspondence, recently published, slips continually between Finnish and Swedish (the language in which he still felt most comfortable). Association with the Järnefelt circle also brought him into close contact with a group of artists, writers and intellectuals, including the painter Akseli GallenKallela, who turned to Finnish folk materials (mythology, landscape and design) as a rich and fertile creative resource. Sibelius found himself, whether by design or accident, to be a key player in demands for an independent Finnish voice. But he swiftly realized that the nationalist route was itself a creatively limiting one, and he increasingly sought to present himself as an artist working on the broader international stage: a strategic decision that brought its own defeats and rewards.