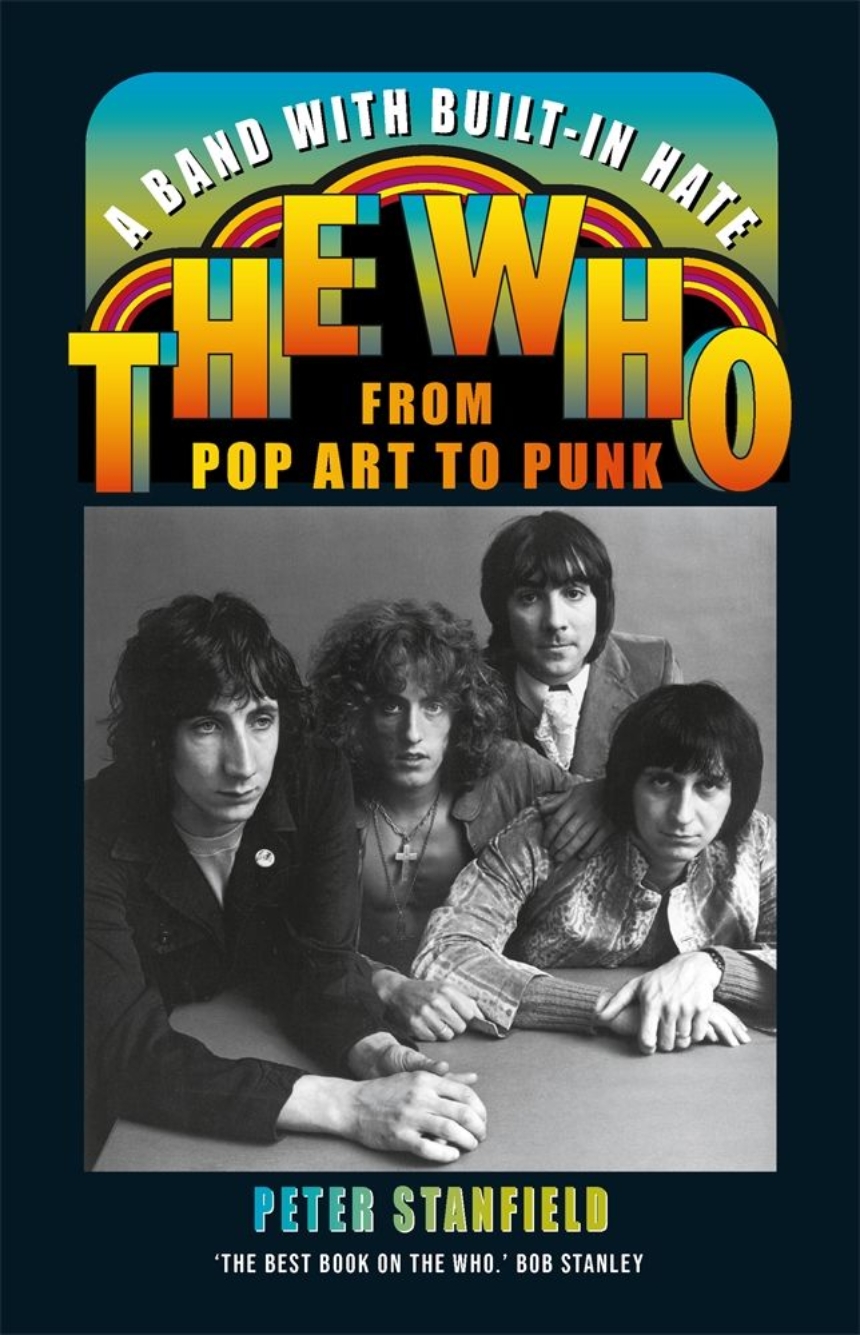

Exploring the explosion of the Who onto the international music scene, this heavily illustrated book looks at this furious band as an embodiment of pop art.

“Ours is music with built-in hatred,” said Pete Townshend. A Band with Built-In Hate pictures the Who from their inception as the Detours in the mid-sixties to the late-seventies, post-Quadrophenia. It is a story of ambition and anger, glamor and grime, viewed through the prism of pop art and the radical leveling of high and low culture that it brought about—a drama that was aggressively performed by the band. Peter Stanfield lays down a path through the British pop revolution, its attitude, and style, as it was uniquely embodied by the Who: first, under the mentorship of arch-mod Peter Meaden, as they learned their trade in the pubs and halls of suburban London; and then with Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, two aspiring filmmakers, at the very center of things in Soho. Guided by contemporary commentators—among them, George Melly, Lawrence Alloway, and most conspicuously Nik Cohn—Stanfield describes a band driven by belligerence and delves into what happened when Townshend, Daltrey, Moon, and Entwistle moved from back-room stages to international arenas, from explosive 45s to expansive concept albums. Above all, he tells of how the Who confronted their lost youth as it was echoed in punk.

“Ours is music with built-in hatred,” said Pete Townshend. A Band with Built-In Hate pictures the Who from their inception as the Detours in the mid-sixties to the late-seventies, post-Quadrophenia. It is a story of ambition and anger, glamor and grime, viewed through the prism of pop art and the radical leveling of high and low culture that it brought about—a drama that was aggressively performed by the band. Peter Stanfield lays down a path through the British pop revolution, its attitude, and style, as it was uniquely embodied by the Who: first, under the mentorship of arch-mod Peter Meaden, as they learned their trade in the pubs and halls of suburban London; and then with Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, two aspiring filmmakers, at the very center of things in Soho. Guided by contemporary commentators—among them, George Melly, Lawrence Alloway, and most conspicuously Nik Cohn—Stanfield describes a band driven by belligerence and delves into what happened when Townshend, Daltrey, Moon, and Entwistle moved from back-room stages to international arenas, from explosive 45s to expansive concept albums. Above all, he tells of how the Who confronted their lost youth as it was echoed in punk.

Reviews

Excerpt

In a moment of rhetorical exuberance, one half of The Who’s management, Kit Lambert, described his charges as being ‘armed against the bourgeois’ in order to act out a ‘new form of crime’. Hyperbole, perhaps, but there is no doubt Lambert had larceny in mind when he started working with the band. With Pete Townshend, he had a co-conspirator willing to translate his felonious ideas into a pop idiom and to put them into practice: ‘Ours is music with built-in hatred,’ Townshend said in 1968. He had been saying much the same since 1965.

Townshend’s spleen, film-maker and critic Tony Palmer explained, ‘is directed against not only the social environment which sponsored and then grew tired of him, but also against the perverse snobbery which damns what he does to the oblivion of freakish irrelevance’. Across The Who’s first ten years of creative activity, the band repeatedly refused the limits imposed on post-war youth and on their chosen art form: pop music. In their mutinous stance The Who traipsed over the conventions of civility and restraint, and paid deference to no one. They were recusants for the new pop age.

The Who’s acts of sedition were especially apparent in the run of singles with which they altered the language of pop, first in maximized attitude with ‘I Can’t Explain’, ‘Anyway Anyhow Anywhere’ and ‘My Generation’ in 1965, and then, just as concisely, in a more stylized manner with ‘Substitute’, ‘I’m a Boy’, ‘Happy Jack’ in 1966, and ‘Pictures of Lily’ and ‘I Can See For Miles’ in 1967. With their amplified assault on what a pop song should sound like and what it might express, The Who played out the roles of delinquent mischief-makers and radical aesthetes, practising an art that was impudent and violent, yet also tenderly disarming.

The Who existed in the contradiction that George Melly had named a ‘revolt into style’. Jazz man, raconteur and dandy at large, Melly, in his own words, had ‘left the waterhole for the hide in the trees’. From his place of concealment, in articles written for the New Statesmen, New Society and The Observer – which were later gathered together as Revolt into Style (1970) – Melly offered his views on the popular or ‘pop’ arts. His columns gave an intimate and at times sharply critical account of the pop events of the 1960s. Melly considered pop to be a subversive passport to ‘the country of now’ that was personified by The Beatles’ repudiation of old or new rules; a lack of deference more aggressively practised by the Rolling Stones. Into the space created by these two bands, The Who arrived like a malcontent younger sibling and ‘succeeded’, wrote Melly, ‘in making The Beatles sound precious and Stones old hat’.

A Band with Built-In Hate is about the new forms of cultural crimes The Who carried out; how their particular revolt into style took form and acquired its edge. In 1965 Townshend said it was ‘a hate of every kind of pop music and a hate of everything our group has done’ that motivated him. Melly’s book offers the immediate context within which to locate the band’s stance of a self-conscious disavowal of the pop ideal – an opposition they refined even as they chased and courted pop success. If Melly was one of the period’s best theorists on pop, its best critic was Nik Cohn, the ‘most respected and influential’ pop commentator on Fleet Street, according to his contemporary Jonathan Aiken. From the mid-1960s to the early 1970s, Cohn wrote with an unrivalled acuity about pop style – and The Who were his finest subject. In tracing his critical take on the band and pop, I will return to the columns he wrote for Queen magazine and the New York Times, where he responded with succinctness and an immediacy to the pop ferment. This material, alongside the more considered ideas in Cohn’s fiction and books, will help to plot out what pop was and could be, and allow us to think again about how The Who slotted into and then reshaped that story.

Cohn’s view of the pop field was singular. Unlike most of his contemporaries in pop journalism, he had strongly held and voiced opinions; pop mattered to Cohn, it was his obsession. He promoted the view of pop as a series of style explosions and flash impressions that were continuously refiguring the everyday. He used pop as a means to inhabit the marvellous, to transform the drab and the boring, to imagine the limits of the possible. He considered The Who to be fellow travellers, young men who were equally fanatic in their obsession with style. The Who made pop into an art worthy of the consideration of a critic with a truant eye and a disposition for the outlandish.

When he described his pop ideal, Cohn invariably labelled it ‘flash’. The adjective had a peculiarly English application; it was not much used in the pop vernacular of the day by American critics. But it summarized the perfect pop attributes, suggesting in its two syllables the flaring, pulsing surge of the ephemeral pop moment: the splashy, garish display of the pop star; the sharp, concise impression left by the hit of a pop single; the sham, counterfeit emotion used in pop marketing; and the illicit, underworld attraction of flash-men, flash-coves and flash-Harrys who occupied the pop world, especially those trespassers who tunnelled under or climbed over the cultural and social borders of the suburban greylands that restrained others. To have ‘flash’ meant you lived in the moment, without regard for yesterday and without thought for tomorrow. You thrived in an accelerating world, ahead of the game, blazing brightly enough to leave an impression – to have made your mark with attitude and style.

As he wrote about the pop moment, Cohn was aware of the contradictions in the stance he struck, warning himself, as much as anyone else, against putting gild on gold and paint on the lily:

Rock ’n’ Roll, like all mass media, works best off trivia, ephemera and general game-playing, and the moment that anyone starts taking it more solemnly, he’s treading on minefields. As performance, it has been magnificent. Nothing has been better at catching moments, and nothing has carried more impact, more evocative energy. While it lives off flash and outrage, impulse, excess and sweet teen romance, it’s perfect. But dabble in Art and immediately it gets overloaded.

The persona of a pop intellectual, which Melly channelled into his journalism, was informed by the artists and critics of the Independent Group who met at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in the early 1950s, among them Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Hamilton, John McHale, Lawrence Alloway, Magda Cordell and Reyner Banham. This group set the terms upon which an understanding and an articulation of the pop arts and, subsequently, British Pop art would be based. In the round, Melly acknowledged the role of this radical collective on his ideas; and The Who, in all their varied activities, engaged wholly and enthusiastically in the debate elucidated in Alloway’s essay ‘The Long Front of Culture’ (1959). Alloway argued that the traditionally educated custodians of the rarefied arts – the elite, with their vehement opposition to the popular – now had no choice but to contend with unruly, mass and industrial arts: the pop arts that clamoured for the public’s attention.

In the post-war context of austerity, Alloway outlined an aesthetics of plenty exemplified by American commercial imagery and products, and challenged the fixed binary of the low and the high. He championed an acceptance of the transformative impact of commercial products, arguing that consumers can develop tastes every bit as discriminating as those held by connoisseurs of the fine arts. This is not to say that the terms and criteria used in these acts of judgement will be the same, but that the times demanded an inclusive rather than exclusive approach to culture. The fine and popular arts are of equal interest; each, he argued, is worthy of critical consideration. Alloway called for the vertiginous pyramid of taste – the vulgar masses at the bottom, the refined elite at the top – to be reimagined as a horizontal continuum. The Who lived and worked on that line and made high art’s link with low consumer culture more visible and more familiar.

You can see the continuum being played out in a story told by The Beatles’ publicist, Derek Taylor: travelling with George Harrison, he was asked by an airline hostess if they were economy or first class? Harrison answered that they were travelling first class but as for being first class that was a matter for debate. The Beatles were both agents in, and symptom of, the dissembling of class barriers. Melly’s Revolt into Style documents the shifts in the reception and making of the pop arts that Alloway had identified; the questioning of accepted notions of good taste, and the collapse of class distinctions in life and art, that The Beatles, the Stones and The Who encouraged.

Townshend’s spleen, film-maker and critic Tony Palmer explained, ‘is directed against not only the social environment which sponsored and then grew tired of him, but also against the perverse snobbery which damns what he does to the oblivion of freakish irrelevance’. Across The Who’s first ten years of creative activity, the band repeatedly refused the limits imposed on post-war youth and on their chosen art form: pop music. In their mutinous stance The Who traipsed over the conventions of civility and restraint, and paid deference to no one. They were recusants for the new pop age.

The Who’s acts of sedition were especially apparent in the run of singles with which they altered the language of pop, first in maximized attitude with ‘I Can’t Explain’, ‘Anyway Anyhow Anywhere’ and ‘My Generation’ in 1965, and then, just as concisely, in a more stylized manner with ‘Substitute’, ‘I’m a Boy’, ‘Happy Jack’ in 1966, and ‘Pictures of Lily’ and ‘I Can See For Miles’ in 1967. With their amplified assault on what a pop song should sound like and what it might express, The Who played out the roles of delinquent mischief-makers and radical aesthetes, practising an art that was impudent and violent, yet also tenderly disarming.

The Who existed in the contradiction that George Melly had named a ‘revolt into style’. Jazz man, raconteur and dandy at large, Melly, in his own words, had ‘left the waterhole for the hide in the trees’. From his place of concealment, in articles written for the New Statesmen, New Society and The Observer – which were later gathered together as Revolt into Style (1970) – Melly offered his views on the popular or ‘pop’ arts. His columns gave an intimate and at times sharply critical account of the pop events of the 1960s. Melly considered pop to be a subversive passport to ‘the country of now’ that was personified by The Beatles’ repudiation of old or new rules; a lack of deference more aggressively practised by the Rolling Stones. Into the space created by these two bands, The Who arrived like a malcontent younger sibling and ‘succeeded’, wrote Melly, ‘in making The Beatles sound precious and Stones old hat’.

A Band with Built-In Hate is about the new forms of cultural crimes The Who carried out; how their particular revolt into style took form and acquired its edge. In 1965 Townshend said it was ‘a hate of every kind of pop music and a hate of everything our group has done’ that motivated him. Melly’s book offers the immediate context within which to locate the band’s stance of a self-conscious disavowal of the pop ideal – an opposition they refined even as they chased and courted pop success. If Melly was one of the period’s best theorists on pop, its best critic was Nik Cohn, the ‘most respected and influential’ pop commentator on Fleet Street, according to his contemporary Jonathan Aiken. From the mid-1960s to the early 1970s, Cohn wrote with an unrivalled acuity about pop style – and The Who were his finest subject. In tracing his critical take on the band and pop, I will return to the columns he wrote for Queen magazine and the New York Times, where he responded with succinctness and an immediacy to the pop ferment. This material, alongside the more considered ideas in Cohn’s fiction and books, will help to plot out what pop was and could be, and allow us to think again about how The Who slotted into and then reshaped that story.

Cohn’s view of the pop field was singular. Unlike most of his contemporaries in pop journalism, he had strongly held and voiced opinions; pop mattered to Cohn, it was his obsession. He promoted the view of pop as a series of style explosions and flash impressions that were continuously refiguring the everyday. He used pop as a means to inhabit the marvellous, to transform the drab and the boring, to imagine the limits of the possible. He considered The Who to be fellow travellers, young men who were equally fanatic in their obsession with style. The Who made pop into an art worthy of the consideration of a critic with a truant eye and a disposition for the outlandish.

When he described his pop ideal, Cohn invariably labelled it ‘flash’. The adjective had a peculiarly English application; it was not much used in the pop vernacular of the day by American critics. But it summarized the perfect pop attributes, suggesting in its two syllables the flaring, pulsing surge of the ephemeral pop moment: the splashy, garish display of the pop star; the sharp, concise impression left by the hit of a pop single; the sham, counterfeit emotion used in pop marketing; and the illicit, underworld attraction of flash-men, flash-coves and flash-Harrys who occupied the pop world, especially those trespassers who tunnelled under or climbed over the cultural and social borders of the suburban greylands that restrained others. To have ‘flash’ meant you lived in the moment, without regard for yesterday and without thought for tomorrow. You thrived in an accelerating world, ahead of the game, blazing brightly enough to leave an impression – to have made your mark with attitude and style.

As he wrote about the pop moment, Cohn was aware of the contradictions in the stance he struck, warning himself, as much as anyone else, against putting gild on gold and paint on the lily:

Rock ’n’ Roll, like all mass media, works best off trivia, ephemera and general game-playing, and the moment that anyone starts taking it more solemnly, he’s treading on minefields. As performance, it has been magnificent. Nothing has been better at catching moments, and nothing has carried more impact, more evocative energy. While it lives off flash and outrage, impulse, excess and sweet teen romance, it’s perfect. But dabble in Art and immediately it gets overloaded.

The persona of a pop intellectual, which Melly channelled into his journalism, was informed by the artists and critics of the Independent Group who met at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in the early 1950s, among them Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Hamilton, John McHale, Lawrence Alloway, Magda Cordell and Reyner Banham. This group set the terms upon which an understanding and an articulation of the pop arts and, subsequently, British Pop art would be based. In the round, Melly acknowledged the role of this radical collective on his ideas; and The Who, in all their varied activities, engaged wholly and enthusiastically in the debate elucidated in Alloway’s essay ‘The Long Front of Culture’ (1959). Alloway argued that the traditionally educated custodians of the rarefied arts – the elite, with their vehement opposition to the popular – now had no choice but to contend with unruly, mass and industrial arts: the pop arts that clamoured for the public’s attention.

In the post-war context of austerity, Alloway outlined an aesthetics of plenty exemplified by American commercial imagery and products, and challenged the fixed binary of the low and the high. He championed an acceptance of the transformative impact of commercial products, arguing that consumers can develop tastes every bit as discriminating as those held by connoisseurs of the fine arts. This is not to say that the terms and criteria used in these acts of judgement will be the same, but that the times demanded an inclusive rather than exclusive approach to culture. The fine and popular arts are of equal interest; each, he argued, is worthy of critical consideration. Alloway called for the vertiginous pyramid of taste – the vulgar masses at the bottom, the refined elite at the top – to be reimagined as a horizontal continuum. The Who lived and worked on that line and made high art’s link with low consumer culture more visible and more familiar.

You can see the continuum being played out in a story told by The Beatles’ publicist, Derek Taylor: travelling with George Harrison, he was asked by an airline hostess if they were economy or first class? Harrison answered that they were travelling first class but as for being first class that was a matter for debate. The Beatles were both agents in, and symptom of, the dissembling of class barriers. Melly’s Revolt into Style documents the shifts in the reception and making of the pop arts that Alloway had identified; the questioning of accepted notions of good taste, and the collapse of class distinctions in life and art, that The Beatles, the Stones and The Who encouraged.