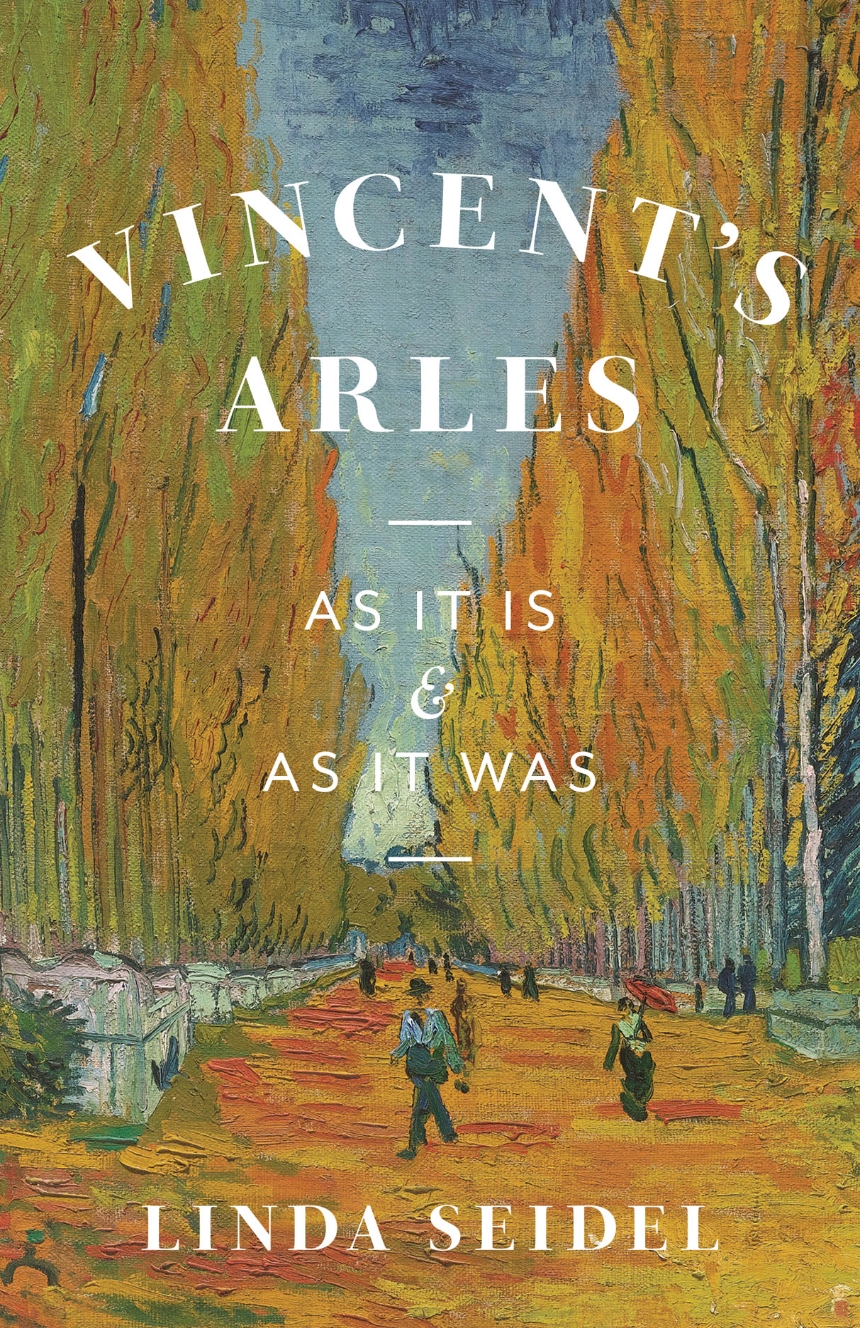

Vincent’s Arles

As It Is and as It Was

A vivid tour of the town of Arles, guided by one of its most famous visitors: Vincent van Gogh.

Once admired as “a little Rome” on the banks of the Rhône, the town of Arles in the south of France had been a place of significance long before the painter Vincent van Gogh arrived in February of 1888. Aware of Arles’s history as a haven for poets, van Gogh spent an intense fifteen months there, scouring the city’s streets and surroundings in search of subjects to paint when he wasn’t thinking about other places or lamenting his woeful circumstances.

In Vincent’s Arles, Linda Seidel serves as a guide to the mysterious and culturally rich town of Arles, taking us to the places immortalized by van Gogh and cherished by innumerable visitors and pilgrims. Drawing on her extensive expertise on the region and the medieval world, Seidel presents Arles then and now as seen by a walker, visiting sites old and new. Roman, Romanesque, and contemporary structures come alive with the help of the letters the artist wrote while in Arles. The result is the perfect blend of history, art, and travel, a chance to visit a lost past and its lingering, often beautiful, traces in the present.

Once admired as “a little Rome” on the banks of the Rhône, the town of Arles in the south of France had been a place of significance long before the painter Vincent van Gogh arrived in February of 1888. Aware of Arles’s history as a haven for poets, van Gogh spent an intense fifteen months there, scouring the city’s streets and surroundings in search of subjects to paint when he wasn’t thinking about other places or lamenting his woeful circumstances.

In Vincent’s Arles, Linda Seidel serves as a guide to the mysterious and culturally rich town of Arles, taking us to the places immortalized by van Gogh and cherished by innumerable visitors and pilgrims. Drawing on her extensive expertise on the region and the medieval world, Seidel presents Arles then and now as seen by a walker, visiting sites old and new. Roman, Romanesque, and contemporary structures come alive with the help of the letters the artist wrote while in Arles. The result is the perfect blend of history, art, and travel, a chance to visit a lost past and its lingering, often beautiful, traces in the present.

160 pages | 8 color plates, 41 halftones | 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 | © 2023

Architecture: European Architecture

Art: European Art

Travel and Tourism: Travel Writing and Guides

Reviews

Table of Contents

Excerpt

Toward the end of October 1888, Vincent van Gogh went to the Alyscamps to paint. He was accompanied by Paul Gauguin, who had just arrived for what turned out to be a shorter stay than either of them foresaw. To get to the burial ground, they had to walk from where they were living, in the yellow house at the northern edge of the city, through a small park outside one of the gates in Arles’s extant wall and along meandering streets, passing either the massive Roman arena in the higher part of town or the twelfth century church of Saint Trophime on the edge of the main square. The ancient cemetery had become, by then, an abruptly abbreviated necropolis. The works they produced there over the course of a couple of days, of tombs amid colorful foliage, record the different perceptions each had of what was still a storied place.

The route reversed the one that pilgrims in the twelfth century would have taken after offering prayers at the burial sites of Gaul’s earliest holy men. From the cemetery, those pious travelers passed through one of the gates in the wall on the city’s south side, stopping at the newly built cathedral to venerate the relics of its patron saint, Trophimus. A short walk north and west took them to the bridge across the Rhône, near the spot on the other side of the river where Genesius, an early martyr, had been headed. As I traced their passage through Arles, imagining places that might have caught their attention, I wondered what they would have thought of them as they passed by. Had they found what they set out to look for as they journeyed, as Vincent had done while en route to Provence?

“I still have in my memory the feeling the journey from Paris to Arles gave me this past winter. How I watched out to see ‘if it was like Japan yet!’” he wrote Gauguin shortly before the latter’s visit.

Vincent’s journey began on Sunday, February 19, 1888. The train he boarded passed through Lyon and traveled alongside the Rhône, through Vienne, before arriving in Arles the following day in the middle of a snowfall. In letters written to his brother and sister soon thereafter, he explained that he had decided to leave Paris because winter in the French capital adversely affected both his health and his work. People were demanding varied and intense colors in paintings, rather than the gray palette he had been using, and he wanted to change his ways. As he traveled, thoughts of contemporary Japanese woodcuts he had been collecting shaped his expectation of what he would see in the Provençal countryside. Even before reaching Arles, he had found what he was searching for from the window of the train: rows of little round trees with olive green or gray-green foliage… plots of red earth... with mountains in the background of the most delicate lilac. And the landscape under the snow with the white peaks against a sky as bright as the snow.

This letter to his younger brother Theo was the first of approximately two hundred Vincent wrote to family members and friends during the more than two years he spent in Provence. For most of that time, he lived in Arles; following his stay there, he moved to an asylum at Saint-Rémy, twenty miles away. The letters to his brother often begin either with a request for money desperately needed for living expenses and art supplies, or with acknowledgment of its receipt: “Thanks for your kind letter and the 50-franc note,” he wrote Theo three days after arriving in Arles. They invariably continue with discussions of the art market, comments on the work of other artists, and recommendations for how Theo should handle dealers in Paris and The Hague. News of Theo’s success in getting Vincent’s work accepted by the fourth Salon of Independent Artists, held in Paris from March 22 to May 3, 1888, reached Arles in early March. Vincent responded with the suggestion that two landscapes he had done in Montmartre the previous year should be submitted. When the show opened, he thanked his brother for the initiative he had taken. “All in all, I’m really pleased that they’ve put them with the other Impressionists,” he wrote, requesting that in future shows he be listed as “Vincent and not Vangogh, for the excellent reason that people here wouldn’t be able to pronounce that name.”

By then, he had found the subject he thought most likely to attract interest, “studies of nature in the south,” telling Theo that the market in The Hague would be the best place to promote his work. Ten days later he sent his brother a lengthy request for supplies, saying, “For Christ’s sake get the paint to me without delay. The season of orchards in blossom is so short, and you know these subjects are among the ones that cheer everyone up.”

Vincent’s letters are best known for their remarkable documentation of some of the most beloved images ever made, which famously (but incorrectly) failed to attract attention during their creator’s lifetime. They also trace a story of ups and downs in the mental and physical health of their writer, aspects of his life that have been sensationalized at the expense of other things about which he wrote at greater length. When Vincent wasn’t wielding a brush or reed pen, he read vigorously, in at least three languages, peppering his letters with recommendations for fa-vorite books and references to texts he found meaningful. He composed still lifes around his favorite tomes and occasionally incorporated “portraits” of what he had been reading into his compositions. In homage to works he admired, he suggested to Theo that the title of another one of the paintings included in the upcoming Independents’ show, a colorful cascade of books he had done before leaving Paris for Arles, should be “Parisian novels.” Its current title, Piles of French Novels and Roses in a Glass, subtly shifts understanding of the subject from celebration of Vincent’s favorite reading to enumeration of his painting’s objects.

Sometimes thoughts Vincent gleaned from his reading collided with what he was painting or looking at, causing him to experience things he saw as imbued with unexpected associations. Trees and flowering bushes, seen during his walks through the verdant Place Lamartine and the public garden, evoked Renaissance poets whose works he knew. This led him to imagine Petrarch and Boccaccio, who had spent time in the region centuries before, seeing things he was also seeing. Sunflowers, rocky outcroppings, and cypress trees, familiar features of the landscape appeared to him as archetypal forms, and he likened the lines and proportions of the trees to those of an Egyptian obelisk, even though that is not how he painted them. What he could not have envisaged was that he would become an equally if not greater iconic presence in the region less than a century after his death.

The route reversed the one that pilgrims in the twelfth century would have taken after offering prayers at the burial sites of Gaul’s earliest holy men. From the cemetery, those pious travelers passed through one of the gates in the wall on the city’s south side, stopping at the newly built cathedral to venerate the relics of its patron saint, Trophimus. A short walk north and west took them to the bridge across the Rhône, near the spot on the other side of the river where Genesius, an early martyr, had been headed. As I traced their passage through Arles, imagining places that might have caught their attention, I wondered what they would have thought of them as they passed by. Had they found what they set out to look for as they journeyed, as Vincent had done while en route to Provence?

“I still have in my memory the feeling the journey from Paris to Arles gave me this past winter. How I watched out to see ‘if it was like Japan yet!’” he wrote Gauguin shortly before the latter’s visit.

Vincent’s journey began on Sunday, February 19, 1888. The train he boarded passed through Lyon and traveled alongside the Rhône, through Vienne, before arriving in Arles the following day in the middle of a snowfall. In letters written to his brother and sister soon thereafter, he explained that he had decided to leave Paris because winter in the French capital adversely affected both his health and his work. People were demanding varied and intense colors in paintings, rather than the gray palette he had been using, and he wanted to change his ways. As he traveled, thoughts of contemporary Japanese woodcuts he had been collecting shaped his expectation of what he would see in the Provençal countryside. Even before reaching Arles, he had found what he was searching for from the window of the train: rows of little round trees with olive green or gray-green foliage… plots of red earth... with mountains in the background of the most delicate lilac. And the landscape under the snow with the white peaks against a sky as bright as the snow.

This letter to his younger brother Theo was the first of approximately two hundred Vincent wrote to family members and friends during the more than two years he spent in Provence. For most of that time, he lived in Arles; following his stay there, he moved to an asylum at Saint-Rémy, twenty miles away. The letters to his brother often begin either with a request for money desperately needed for living expenses and art supplies, or with acknowledgment of its receipt: “Thanks for your kind letter and the 50-franc note,” he wrote Theo three days after arriving in Arles. They invariably continue with discussions of the art market, comments on the work of other artists, and recommendations for how Theo should handle dealers in Paris and The Hague. News of Theo’s success in getting Vincent’s work accepted by the fourth Salon of Independent Artists, held in Paris from March 22 to May 3, 1888, reached Arles in early March. Vincent responded with the suggestion that two landscapes he had done in Montmartre the previous year should be submitted. When the show opened, he thanked his brother for the initiative he had taken. “All in all, I’m really pleased that they’ve put them with the other Impressionists,” he wrote, requesting that in future shows he be listed as “Vincent and not Vangogh, for the excellent reason that people here wouldn’t be able to pronounce that name.”

By then, he had found the subject he thought most likely to attract interest, “studies of nature in the south,” telling Theo that the market in The Hague would be the best place to promote his work. Ten days later he sent his brother a lengthy request for supplies, saying, “For Christ’s sake get the paint to me without delay. The season of orchards in blossom is so short, and you know these subjects are among the ones that cheer everyone up.”

Vincent’s letters are best known for their remarkable documentation of some of the most beloved images ever made, which famously (but incorrectly) failed to attract attention during their creator’s lifetime. They also trace a story of ups and downs in the mental and physical health of their writer, aspects of his life that have been sensationalized at the expense of other things about which he wrote at greater length. When Vincent wasn’t wielding a brush or reed pen, he read vigorously, in at least three languages, peppering his letters with recommendations for fa-vorite books and references to texts he found meaningful. He composed still lifes around his favorite tomes and occasionally incorporated “portraits” of what he had been reading into his compositions. In homage to works he admired, he suggested to Theo that the title of another one of the paintings included in the upcoming Independents’ show, a colorful cascade of books he had done before leaving Paris for Arles, should be “Parisian novels.” Its current title, Piles of French Novels and Roses in a Glass, subtly shifts understanding of the subject from celebration of Vincent’s favorite reading to enumeration of his painting’s objects.

Sometimes thoughts Vincent gleaned from his reading collided with what he was painting or looking at, causing him to experience things he saw as imbued with unexpected associations. Trees and flowering bushes, seen during his walks through the verdant Place Lamartine and the public garden, evoked Renaissance poets whose works he knew. This led him to imagine Petrarch and Boccaccio, who had spent time in the region centuries before, seeing things he was also seeing. Sunflowers, rocky outcroppings, and cypress trees, familiar features of the landscape appeared to him as archetypal forms, and he likened the lines and proportions of the trees to those of an Egyptian obelisk, even though that is not how he painted them. What he could not have envisaged was that he would become an equally if not greater iconic presence in the region less than a century after his death.