Distributed for Seagull Books

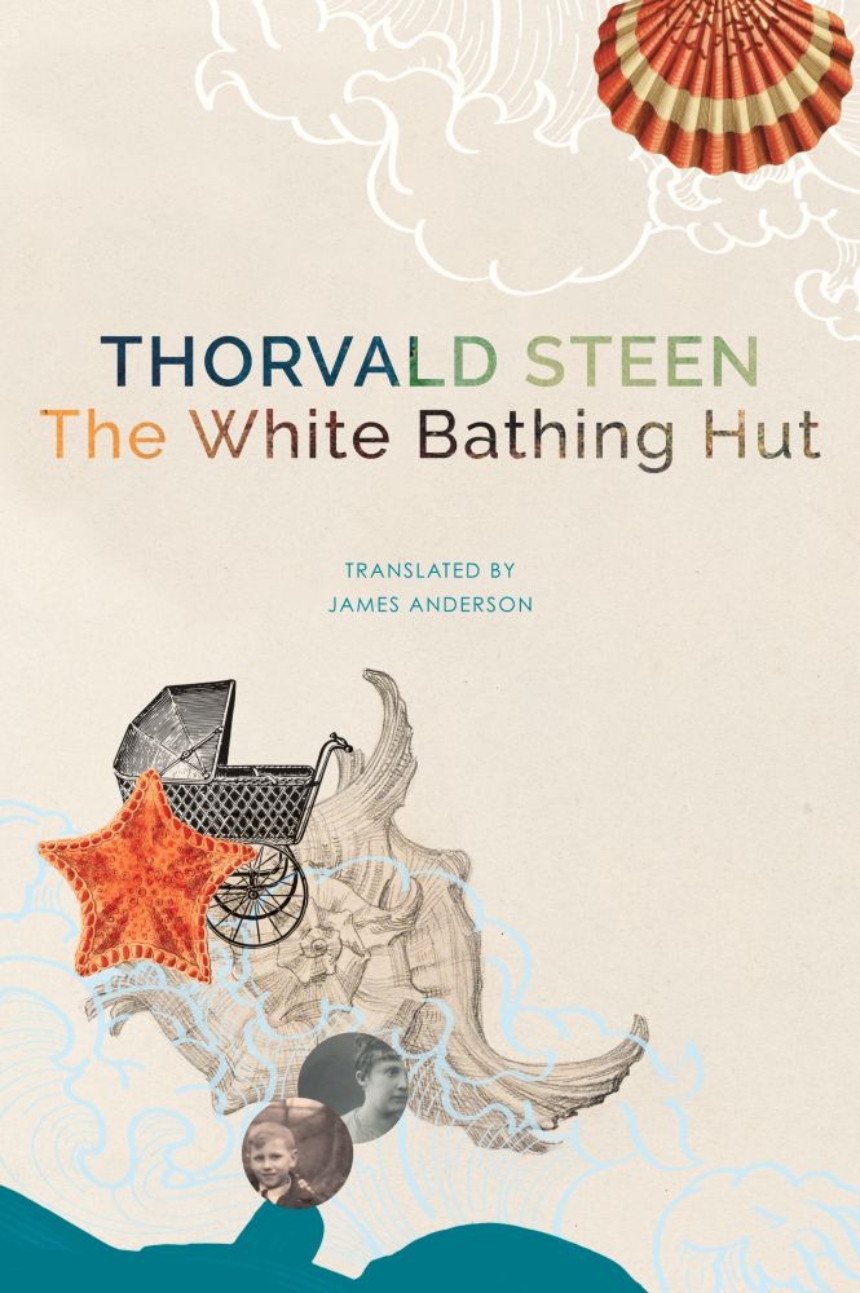

The White Bathing Hut

A novel about disability, family secrets, and Norway’s eugenic past.

The White Bathing Hut is a genetic detective story. The narrator uses a wheelchair because of an inherited illness that has caused his muscle tissue to degenerate, making him unable to walk. One day, he falls from his wheelchair. His family is away, his cell phone out of reach, and he has no choice but to lie on the floor of his apartment, dissecting his life, until help arrives. He recalls his parents’ reactions of shame and silence when, as a teenager, his illness was first diagnosed. Now in her old age, his mother remains stubbornly secretive. A chance call from a cousin provides the narrator with clues about his grandfather and uncle, whom he never met and who both also had the disease. His search for the truth about his heredity is given new urgency when his mother is diagnosed with cancer. He must persuade her to speak before she dies, for his own sake and for his daughter’s. The White Bathing Hut is an indictment of contemporary Norwegian society, which claims to abhor its history of eugenics, yet still seeks to control the lives of people with disabilities.

The White Bathing Hut is a genetic detective story. The narrator uses a wheelchair because of an inherited illness that has caused his muscle tissue to degenerate, making him unable to walk. One day, he falls from his wheelchair. His family is away, his cell phone out of reach, and he has no choice but to lie on the floor of his apartment, dissecting his life, until help arrives. He recalls his parents’ reactions of shame and silence when, as a teenager, his illness was first diagnosed. Now in her old age, his mother remains stubbornly secretive. A chance call from a cousin provides the narrator with clues about his grandfather and uncle, whom he never met and who both also had the disease. His search for the truth about his heredity is given new urgency when his mother is diagnosed with cancer. He must persuade her to speak before she dies, for his own sake and for his daughter’s. The White Bathing Hut is an indictment of contemporary Norwegian society, which claims to abhor its history of eugenics, yet still seeks to control the lives of people with disabilities.

Reviews

Excerpt

I was fifteen and growing up. I took it for granted that my body would get stronger with each passing year and achieve greater and greater things. Nothing was more important than doing a long and faultless ski jump. My goal was to jump at Holmenkollen.

In December, just before the start of the 1971 skiing season, I was sent to the doctor after falling at the end of every jump during our first snow-training at Linderudkollen. My coach and I both felt frustrated. We thought it was muscle strain. To comfort me, my coach announced that it could hap-pen to anyone, even the best.

A biopsy, a piece of muscle fibre from my thigh, showed that I was suffering from a chronic disease—progressive muscular dystrophy of the facioscapulohumeral type. It affects one in twenty thousand people and is found in all variants, from mild to aggressive. It’s a muscle-wasting disease which gradually causes paralysis in the face, shoulders, upper arms, hips and legs. I would be risking serious injury on the jump-slope, the neurologist told me. He insisted that I give up ski jumping immediately.

‘Forever?’ I asked.

‘Forever.’ the neurologist said.

He’d sentenced me never to fly again. He assumed I’d be confined to a wheelchair within five years, and that I’d be bedridden by the age of thirty.

The doctor explained that it was a disease that both sexes can inherit. He made me promise to tell my parents about our conversation.

When my mother and father came back from work that day, they asked how things had gone at the doctor’s. I replied that everything was fine and that I’d merely got muscle strain. A week later the neurologist phoned my father. Next day, at dinner, my mother said that I wasn’t to tell anyone about my illness. My father didn’t contradict her.

A couple of weeks later I laid a questionnaire on the table. It was from the school nurse asking if there was any chronic disease in our family. Mother ticked ‘no’ and said that if I told the truth about my condition they would use it against me, and us. ‘The school will treat you differently to the others, treat you like a victim. Would you enjoy that?’ she asked. Should a potential employer learn of the illness in the future, it would be an excuse not to employ me, she said. I read my father’s silence as acquiescence. I nodded.

Four months later, I was confirmed. I didn’t let any of the guests, ski-jumping friends or my coach into the secret.

In December, just before the start of the 1971 skiing season, I was sent to the doctor after falling at the end of every jump during our first snow-training at Linderudkollen. My coach and I both felt frustrated. We thought it was muscle strain. To comfort me, my coach announced that it could hap-pen to anyone, even the best.

A biopsy, a piece of muscle fibre from my thigh, showed that I was suffering from a chronic disease—progressive muscular dystrophy of the facioscapulohumeral type. It affects one in twenty thousand people and is found in all variants, from mild to aggressive. It’s a muscle-wasting disease which gradually causes paralysis in the face, shoulders, upper arms, hips and legs. I would be risking serious injury on the jump-slope, the neurologist told me. He insisted that I give up ski jumping immediately.

‘Forever?’ I asked.

‘Forever.’ the neurologist said.

He’d sentenced me never to fly again. He assumed I’d be confined to a wheelchair within five years, and that I’d be bedridden by the age of thirty.

The doctor explained that it was a disease that both sexes can inherit. He made me promise to tell my parents about our conversation.

When my mother and father came back from work that day, they asked how things had gone at the doctor’s. I replied that everything was fine and that I’d merely got muscle strain. A week later the neurologist phoned my father. Next day, at dinner, my mother said that I wasn’t to tell anyone about my illness. My father didn’t contradict her.

A couple of weeks later I laid a questionnaire on the table. It was from the school nurse asking if there was any chronic disease in our family. Mother ticked ‘no’ and said that if I told the truth about my condition they would use it against me, and us. ‘The school will treat you differently to the others, treat you like a victim. Would you enjoy that?’ she asked. Should a potential employer learn of the illness in the future, it would be an excuse not to employ me, she said. I read my father’s silence as acquiescence. I nodded.

Four months later, I was confirmed. I didn’t let any of the guests, ski-jumping friends or my coach into the secret.