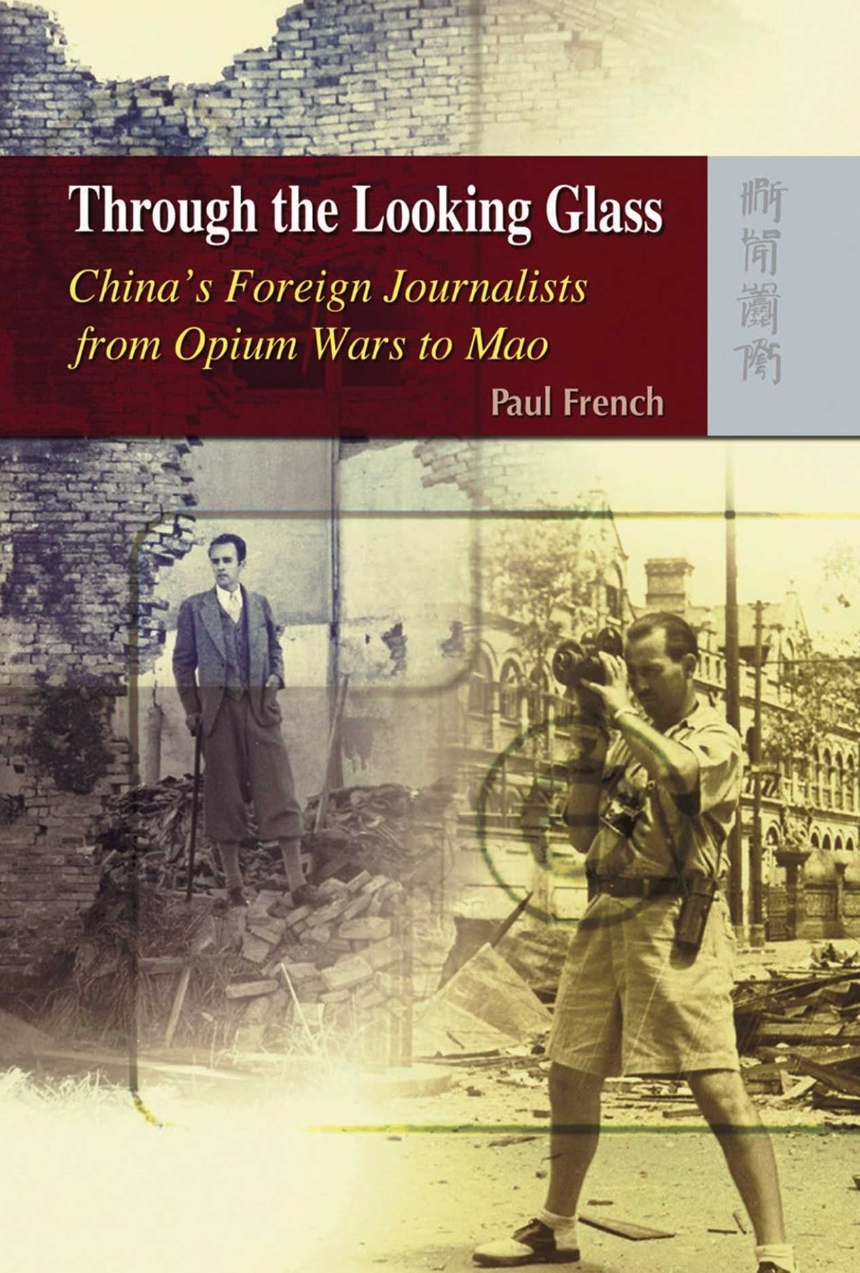

Through the Looking Glass

China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao

9789622099821

Distributed for Hong Kong University Press

Through the Looking Glass

China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao

The convulsive history of foreign journalists in China starts with the newspapers printed in the European Factories of Canton in the 1820s and ends with the Communist revolution in 1949. It also starts with a duel between two editors over the China’s future and ends with a fistfight in Shanghai over the revolution. The men and women of the foreign press experienced China’s history and development; its convulsions and upheavals; revolutions and wars. They had front row seats at every major twist and turn in China’s fortunes. They reported on the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion; saw the Summer Palace burn; endured the Boxer Rebellion; witnessed the Qing Dynasty’s death, the birth of a Nationalist China and its struggle for survival against rampant warlordism. They followed the rise of the Communists, total war and then revolution. When the Unequal Treaties were signed, the foreign press were there; when foreign troops occupied and looted Beijing in 1900 they were present too; they saw the Republic born in 1911 and an increasingly politically strident China assert itself on May Fourth 1919. Foreign journalists stood in the streets witnessing the blood letting of the First Shanghai War in 1932 and then were blown of their feet by the bombing of the Second Shanghai War in 1937. They tracked Japanese aggression from the annexation of Manchuria, the fall of Shanghai and the Rape of Nanjing through to the assault on the Nationalist wartime capital of Chongqing as they cowered in the same bomb shelters as everybody else. They witnessed the fratricidal Civil War, the flight of Chiang Kai-shek to Taiwan and the early days of the People’s Republic. The old China press corps were the witnesses and the primary interpreters to millions globally of the history of modern China and they were themselves a cast of fascinating characters. Like journalists everywhere they took sides, they brought their own assumptions and prejudices to China along with their hopes, dreams and fears. They weren’t infallible; they got the story completely wrong as often as they got it partially right. They were a mixed bunch—from long timers such as George ‘Morrison of Peking’; glamorous journalist-sojourners such as Peter Fleming and Emily Hahn; and reporter-tourists such as Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn along with numerous less celebrated, but no less interesting, members of the old China press corps. A fair few were drunks, philanderers and frauds; more than one was a spy—they changed sides, they lost their impartiality, they displayed bias and a few were downright scoundrels and liars. But most did their job ably and professionally, some passionately and a select few with rare flair and touches of genius.

312 pages | 6 x 9

History: General History

Language and Linguistics: Language and Law

Sociology: General Sociology