9781914982019

9781913368265

9781909961777

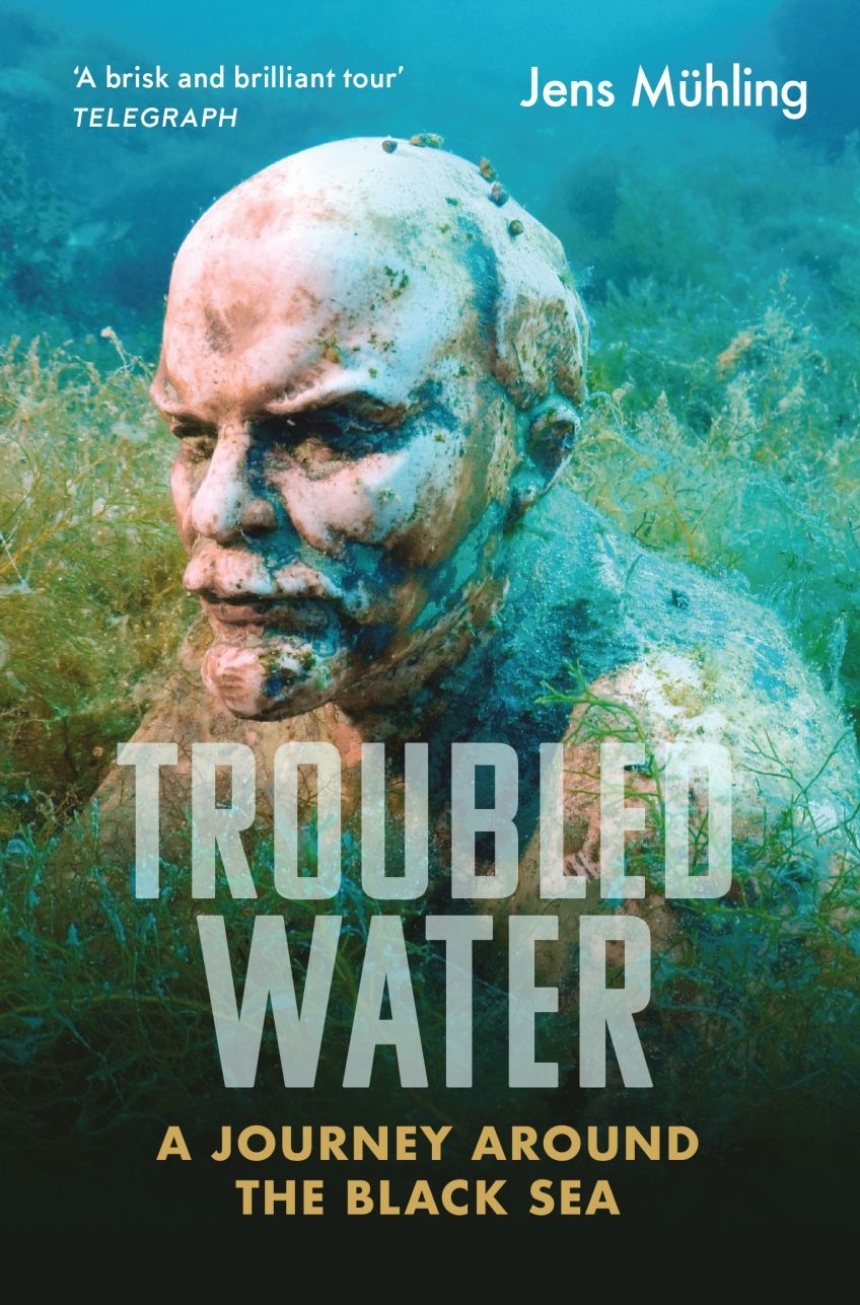

A history of the countries bordering the Black Sea told through the stories of the people who live there.

Fringing the Black Sea is a diverse array of countries, some centuries old and others emerging only after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Jens Mühling travels through this region, telling the stories of the people he meets along the way in order to paint a picture of the mix of cultures found here and to understand the present against a history stretching back to the arrival of Ancient Greek settlers and beyond.

A fluent Russian speaker with a knack for gaining the trust of those he meets, Mühling brings together a cast of characters as diverse as the stories he hears, all of whom are willing to tell him their complex, contradictory, and often fantastical tales full of grief and legend. He meets descendants of the so-called Pontic Greeks, whom Stalin deported to Central Asia and who have now returned; Circassians who fled to Syria a century ago and whose great-great-grandchildren have returned to Abkhazia; and members of ethnic minorities like the Georgian Mingrelians or Bulgarian Muslims, expelled to Turkey in the summer of 1989. Mühling captures the region’s uneasy alliance of tradition and modernity and the diverse humanity of those who live there.

Fringing the Black Sea is a diverse array of countries, some centuries old and others emerging only after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Jens Mühling travels through this region, telling the stories of the people he meets along the way in order to paint a picture of the mix of cultures found here and to understand the present against a history stretching back to the arrival of Ancient Greek settlers and beyond.

A fluent Russian speaker with a knack for gaining the trust of those he meets, Mühling brings together a cast of characters as diverse as the stories he hears, all of whom are willing to tell him their complex, contradictory, and often fantastical tales full of grief and legend. He meets descendants of the so-called Pontic Greeks, whom Stalin deported to Central Asia and who have now returned; Circassians who fled to Syria a century ago and whose great-great-grandchildren have returned to Abkhazia; and members of ethnic minorities like the Georgian Mingrelians or Bulgarian Muslims, expelled to Turkey in the summer of 1989. Mühling captures the region’s uneasy alliance of tradition and modernity and the diverse humanity of those who live there.

Reviews

Table of Contents

The Flood 1

Prologue

Russia 21

Chornoye more / ??¨???? ????

The beginnings of a bridge • Hotel Fortuna •

Pasha the Turk • Greek wine • Horseless Cossacks •

A Black Sea lexicon, entry no. 1: Rapana venosa •

A Caucasian without a moustache

Georgia 77

Shavi zghva / ???? ????

The thieves of Poti • A Black Sea lexicon, entry no. 2:

Engraulis encrasilocus • Swimming trees

Abkhazia 101

Amshyn Eikwa / ????? ?????

A long story • The monkeys of Sukhum •

The return of the Circassians

Turkey 129

Karadeniz

Firtina the falcon • An icon falls from the sky •

The love story of Gabi and Yusuf • Amazon island •

Atatu¨rk’s eyes • In the wake of the Argo •

A Black Sea lexicon, entry no. 3: Bosporus

Bulgaria 177

Cherno more / ????? ????

The renamed • Frogmen • The Sozopol vampire •

A Black Sea lexicon, entry no. 4: Hydrogen sulphide

Romania 205

Marea Neagra?

The wrong horse • Ovid’s last metamorphosis •

The Black Danube

Ukraine 233

Chorne more / ?o??? ????

The spring at Kyrnychky • A coincidence in Odessa •

Antelopes on the steppe • A Black Sea lexicon,

entry no. 5: Mnemiopsis leidyi

Crimea 263

Qara deñiz

Tracks in the snow • Today we, tomorrow you •

The love story of Alla and Vladimir • The end of a bridge

The Ark 291

Epilogue

Acknowledgements 301

Bibliography 303

Prologue

Russia 21

Chornoye more / ??¨???? ????

The beginnings of a bridge • Hotel Fortuna •

Pasha the Turk • Greek wine • Horseless Cossacks •

A Black Sea lexicon, entry no. 1: Rapana venosa •

A Caucasian without a moustache

Georgia 77

Shavi zghva / ???? ????

The thieves of Poti • A Black Sea lexicon, entry no. 2:

Engraulis encrasilocus • Swimming trees

Abkhazia 101

Amshyn Eikwa / ????? ?????

A long story • The monkeys of Sukhum •

The return of the Circassians

Turkey 129

Karadeniz

Firtina the falcon • An icon falls from the sky •

The love story of Gabi and Yusuf • Amazon island •

Atatu¨rk’s eyes • In the wake of the Argo •

A Black Sea lexicon, entry no. 3: Bosporus

Bulgaria 177

Cherno more / ????? ????

The renamed • Frogmen • The Sozopol vampire •

A Black Sea lexicon, entry no. 4: Hydrogen sulphide

Romania 205

Marea Neagra?

The wrong horse • Ovid’s last metamorphosis •

The Black Danube

Ukraine 233

Chorne more / ?o??? ????

The spring at Kyrnychky • A coincidence in Odessa •

Antelopes on the steppe • A Black Sea lexicon,

entry no. 5: Mnemiopsis leidyi

Crimea 263

Qara deñiz

Tracks in the snow • Today we, tomorrow you •

The love story of Alla and Vladimir • The end of a bridge

The Ark 291

Epilogue

Acknowledgements 301

Bibliography 303

Excerpt

Prologue

We saw them coming towards us as we travelled the last few miles to Mount Ararat, in eastern Anatolia, where Turkey borders Armenia and Iran amid endless slopes of scree. They were walking along the sides of the road in small groups – men, most of them young with dark beards and nothing in their hands, except for a few carrying small plastic bags. It was March, and snow still lay on the winding pass roads. I wondered how fast you would have to walk in these men’s thin jackets if you didn’t want to freeze.

Mustafa, whose taxi I’d got into in Agri because the next bus to Dogubayazit left only the following day, motioned with his chin to the walkers beyond the windscreen.

The moustache hardened into a line when I tried to persuade Mustafa to stop the car. I wanted to talk to the refugees and ask them what they needed, even if I’d almost certainly be unable to provide it. Forget it, said Mustafa’s frozen moustache. Not for all the lira in the world.

We drove on towards Mount Ararat, which has an ancient and enigmatic bond with the Black Sea. Again and again, men would come around a bend in the road, in twos, five at once, then none for a long time, then suddenly a dozen followed by another dozen – and for a moment I was convinced that the road beyond the next bend would be black with people. but then no one else appeared for ages.

Every time a bunch of men approached us out of the distance, Mustafa would briefly take his hands off the steering wheel, turn his palms to the sky, and shake his head in silent bemusement, as if he were asking himself, or me, or maybe god, what on earth was to be done with all these people who could not stay where they were.

* * *

I’ve seen the Black Sea from all sides, and from none of them was it black.

It was silvery as I drove along the deserted beaches of the Russian Caucasus coast in the spring, as silvery as the skin of the dolphins hugging the shore as they pursued shoals of fish northwards.

It turned blue in May as I reached Georgia, the ancient Colchis of Greek legend, where the beaches are black but not the water.

In Turkey it seemed to take on the green of the tea plantations and hazelnut groves along its shores, and it was still green when I reached the Bosporus in late summer.

The first storms of autumn coloured it brown as the birds headed south and the tourists headed home over the Bulgarian coast.

In Romania’s Danube delta the sky seemed to hang so low over the sea that its lead-grey colour rubbed off on the water.

When I reached Ukraine, the waves scraped dirt-grey ice along the beaches.

Only in Crimea did the winter sun brighten the sea again, and here it assumed the hue it will forever have in my memory – a cloudy, milky green, like a soup of algae and sun cream.

* * *

Journeys seldom start where we remember their starting. This one may well have begun under my blind grandmother’s dining table.

Occasionally, as the grown-ups traded their grown-up stories, my sister and I would crawl between their legs to the end of the table, where grandma sat. We would creep up quietly behind her chair. The back was wickerwork, the holes big enough for us to poke our fingertips through. We would prod grandma in her bony back and, although she had heard rather than seen us coming, she never failed to greet our recurring prank with an indulgent, horrified shriek.

‘oh, are those mice I can feel?’

Squeaking, we would pull our mousy fingers out of the back of the chair and scuttle back under the table

In Neunkirchen, the small town in the Siegerland area of western Germany where my grandmother lived until her death, stands a memorial:

I was to find out from my aunt Gertraude and her Neunkirchen friends Elfriede and Ingeborg at a family Christmas many years later that I wasn’t the only one with his eye on The Admiral’s money. in my grandmother’s hometown there is, besides the memorial to the seafarer, a street called the Van Kinsbergen Ring. Local people call it the ‘potato bug ring’ in view of the amazing number of needy Neunkircheners who came crawling out of the woodwork after van Kinsbergen’s death, claiming to be related to the generous admiral. hisalleged descendants had multiplied like potato bugs.

That Christmas, Gertraude, Elfriede, and Ingeborg also told me that the legacy payments from Holland had dried up long ago – my treasure trove had apparently been confiscated as reparations after the Second World War.

To digest my disappointment, I began to compare my childhood memories of The Admiral with his real-life biography. I learned that it was not van Kinsbergen himself but his father who had emigrated from the impoverished Siegerland in the early eighteenth century to sign up as a soldier in Holland. He had swapped his German surname, Ginsberg, for the more common local variant Kinsbergen when he married a Dutch woman, with whom he had a son named Jan Hendrik. (In an interesting inversion of his father’s self-renaming, Jan Hendrik was identified as Johann Heinrich on his memorial in the Siegerland, due to the contemporary practice of translating foreign names into their German variants.)

The immigrant’s scion joined the navy at fifteen. I realised with some perplexity that the man who would later become an admiral had gone to sea not only for the Dutch crown but for the Russians too. In his mid-thirties, van Kinsbergen had accepted Catherine the great’s offer of joining the tsarina’s war against the Turks and commanding part of her fleet, which had recently made its first sorties into the Black Sea. in 1773, van Kinsbergen engaged a considerably larger Turkish force off the Crimean coast with two gunboats and, after a battle lasting several hours, put them to flight. This skirmish at balaclava was Russia’s first naval battle on the black Sea and, thanks to my alleged great-great-great-great-great-grand-father, it resulted in a great victory.

I wasn’t sure if this was any cause for pride. Catherine’s campaign against the Turks, which van Kinsbergen continued to support in the following years, ended in 1774 with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. Russia did what the world’s largest country had always loved doing – it grew. Catherine incorporated into her empire large swathes of the northern Black Sea coast that had previously been controlled by the Crimean Tatars, allies of the Turks. A few years later, after van Kinsbergen had returned to Holland bedecked with Russian medals, the tsarina went one step further. She subjugated the Tatars and annexed their Crimean homeland. The peninsula, Catherine declared in 1783, would be Russian ‘from now on and for all time’.

In order to conceal the fact that Crimea had ever been anything but Russian, Catherine erased almost all traces of the Tatars. Mosques and madrasahs, caravanserais and khans’ palaces were razed, and the first of several waves of Tatar refugees set out for Ottoman shores.

This wasn’t the first time – and it wouldn’t be the last – that roads around the Black Sea turned black with huddled masses as autocrats transplanted whole peoples and extinguished all sign of them from history.

We saw them coming towards us as we travelled the last few miles to Mount Ararat, in eastern Anatolia, where Turkey borders Armenia and Iran amid endless slopes of scree. They were walking along the sides of the road in small groups – men, most of them young with dark beards and nothing in their hands, except for a few carrying small plastic bags. It was March, and snow still lay on the winding pass roads. I wondered how fast you would have to walk in these men’s thin jackets if you didn’t want to freeze.

Mustafa, whose taxi I’d got into in Agri because the next bus to Dogubayazit left only the following day, motioned with his chin to the walkers beyond the windscreen.

‘Pasaport yok, para yok.’

No passport, no money.

I looked at him quizzically. ‘Syrians?’

He shook his head. ‘Afganlar.’

They must have come to Turkey via Iran, I thought.

No passport, no money.

I looked at him quizzically. ‘Syrians?’

He shook his head. ‘Afganlar.’

They must have come to Turkey via Iran, I thought.

Mustafa nodded as if he could read my mind. ‘Afghanistan – Iran – Istanbul.’

He was silent for a moment before a grin splayed his moustache. ‘Istanbul – Almanya!’ he said, suggesting that the Afghans’ intended destination was my home country.The moustache hardened into a line when I tried to persuade Mustafa to stop the car. I wanted to talk to the refugees and ask them what they needed, even if I’d almost certainly be unable to provide it. Forget it, said Mustafa’s frozen moustache. Not for all the lira in the world.

We drove on towards Mount Ararat, which has an ancient and enigmatic bond with the Black Sea. Again and again, men would come around a bend in the road, in twos, five at once, then none for a long time, then suddenly a dozen followed by another dozen – and for a moment I was convinced that the road beyond the next bend would be black with people. but then no one else appeared for ages.

Every time a bunch of men approached us out of the distance, Mustafa would briefly take his hands off the steering wheel, turn his palms to the sky, and shake his head in silent bemusement, as if he were asking himself, or me, or maybe god, what on earth was to be done with all these people who could not stay where they were.

* * *

I’ve seen the Black Sea from all sides, and from none of them was it black.

It was silvery as I drove along the deserted beaches of the Russian Caucasus coast in the spring, as silvery as the skin of the dolphins hugging the shore as they pursued shoals of fish northwards.

It turned blue in May as I reached Georgia, the ancient Colchis of Greek legend, where the beaches are black but not the water.

In Turkey it seemed to take on the green of the tea plantations and hazelnut groves along its shores, and it was still green when I reached the Bosporus in late summer.

The first storms of autumn coloured it brown as the birds headed south and the tourists headed home over the Bulgarian coast.

In Romania’s Danube delta the sky seemed to hang so low over the sea that its lead-grey colour rubbed off on the water.

When I reached Ukraine, the waves scraped dirt-grey ice along the beaches.

Only in Crimea did the winter sun brighten the sea again, and here it assumed the hue it will forever have in my memory – a cloudy, milky green, like a soup of algae and sun cream.

* * *

Journeys seldom start where we remember their starting. This one may well have begun under my blind grandmother’s dining table.

Occasionally, as the grown-ups traded their grown-up stories, my sister and I would crawl between their legs to the end of the table, where grandma sat. We would creep up quietly behind her chair. The back was wickerwork, the holes big enough for us to poke our fingertips through. We would prod grandma in her bony back and, although she had heard rather than seen us coming, she never failed to greet our recurring prank with an indulgent, horrified shriek.

‘oh, are those mice I can feel?’

Squeaking, we would pull our mousy fingers out of the back of the chair and scuttle back under the table

In Neunkirchen, the small town in the Siegerland area of western Germany where my grandmother lived until her death, stands a memorial:

JOH. HEINRICH VON KINSBERGEN

LIEUT.-ADMIRAL

BENFACTOR OF THE POOR

(1.5.173-22.5.1819)

The admiral’s name – or, rather, not his name but his title – cropped up from time to time in the grown-up conversations on which my sister and I eavesdropped from under the table. ‘The admiral’ stuck in my childhood memory like some kind of semi-mythical character. From what I could grasp, he was a distant relative of ours, a great-great-great-great-great-grandfather who had pitched up in Holland back in the mists of time and acquired considerable fame and wealth there as a seafarer. He had left part of his vast fortune as a fund that, on request, offered grants to impoverished family members back home in the Siegerland. In my imagination, ‘The admiral’s money’ that the adults occasionally mentioned in Neunkirchen took on the proportions of a pirate’s treasure trove, a glittering stash of gold coins just waiting to be discovered by me, The Admiral’s legitimate heir.LIEUT.-ADMIRAL

BENFACTOR OF THE POOR

(1.5.173-22.5.1819)

I was to find out from my aunt Gertraude and her Neunkirchen friends Elfriede and Ingeborg at a family Christmas many years later that I wasn’t the only one with his eye on The Admiral’s money. in my grandmother’s hometown there is, besides the memorial to the seafarer, a street called the Van Kinsbergen Ring. Local people call it the ‘potato bug ring’ in view of the amazing number of needy Neunkircheners who came crawling out of the woodwork after van Kinsbergen’s death, claiming to be related to the generous admiral. hisalleged descendants had multiplied like potato bugs.

That Christmas, Gertraude, Elfriede, and Ingeborg also told me that the legacy payments from Holland had dried up long ago – my treasure trove had apparently been confiscated as reparations after the Second World War.

To digest my disappointment, I began to compare my childhood memories of The Admiral with his real-life biography. I learned that it was not van Kinsbergen himself but his father who had emigrated from the impoverished Siegerland in the early eighteenth century to sign up as a soldier in Holland. He had swapped his German surname, Ginsberg, for the more common local variant Kinsbergen when he married a Dutch woman, with whom he had a son named Jan Hendrik. (In an interesting inversion of his father’s self-renaming, Jan Hendrik was identified as Johann Heinrich on his memorial in the Siegerland, due to the contemporary practice of translating foreign names into their German variants.)

The immigrant’s scion joined the navy at fifteen. I realised with some perplexity that the man who would later become an admiral had gone to sea not only for the Dutch crown but for the Russians too. In his mid-thirties, van Kinsbergen had accepted Catherine the great’s offer of joining the tsarina’s war against the Turks and commanding part of her fleet, which had recently made its first sorties into the Black Sea. in 1773, van Kinsbergen engaged a considerably larger Turkish force off the Crimean coast with two gunboats and, after a battle lasting several hours, put them to flight. This skirmish at balaclava was Russia’s first naval battle on the black Sea and, thanks to my alleged great-great-great-great-great-grand-father, it resulted in a great victory.

I wasn’t sure if this was any cause for pride. Catherine’s campaign against the Turks, which van Kinsbergen continued to support in the following years, ended in 1774 with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. Russia did what the world’s largest country had always loved doing – it grew. Catherine incorporated into her empire large swathes of the northern Black Sea coast that had previously been controlled by the Crimean Tatars, allies of the Turks. A few years later, after van Kinsbergen had returned to Holland bedecked with Russian medals, the tsarina went one step further. She subjugated the Tatars and annexed their Crimean homeland. The peninsula, Catherine declared in 1783, would be Russian ‘from now on and for all time’.

In order to conceal the fact that Crimea had ever been anything but Russian, Catherine erased almost all traces of the Tatars. Mosques and madrasahs, caravanserais and khans’ palaces were razed, and the first of several waves of Tatar refugees set out for Ottoman shores.

This wasn’t the first time – and it wouldn’t be the last – that roads around the Black Sea turned black with huddled masses as autocrats transplanted whole peoples and extinguished all sign of them from history.