A beautifully tailored history of this fashion staple—at once a garment of tradition, power, and subversion.

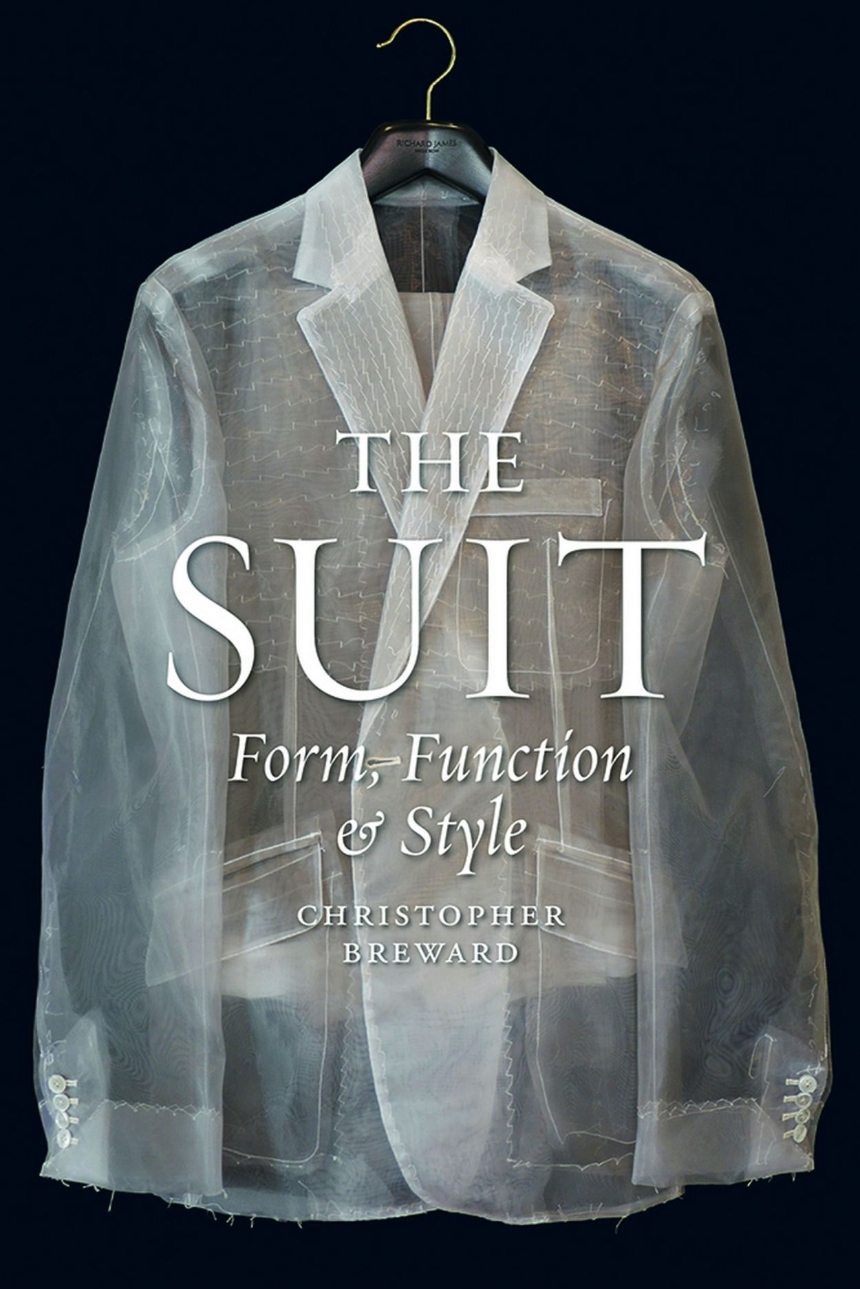

The Suit unpicks the story of this most familiar garment, from its emergence in western Europe at the end of the seventeenth century to today. Suit-wearing figures such as the Savile Row gentleman and the Wall Street businessman have long embodied ideas of tradition, masculinity, power, and respectability, but the suit has also been used to disrupt concepts of gender and conformity. Adopted and subverted by women, artists, musicians, and social revolutionaries through the decades—from dandies and Sapeurs to the Zoot Suit and Le Smoking—the suit is also a device for challenging the status quo. For all those interested in the history of menswear, this beautifully illustrated book offers new perspectives on this most mundane, and poetic, product of modern culture.

The Suit unpicks the story of this most familiar garment, from its emergence in western Europe at the end of the seventeenth century to today. Suit-wearing figures such as the Savile Row gentleman and the Wall Street businessman have long embodied ideas of tradition, masculinity, power, and respectability, but the suit has also been used to disrupt concepts of gender and conformity. Adopted and subverted by women, artists, musicians, and social revolutionaries through the decades—from dandies and Sapeurs to the Zoot Suit and Le Smoking—the suit is also a device for challenging the status quo. For all those interested in the history of menswear, this beautifully illustrated book offers new perspectives on this most mundane, and poetic, product of modern culture.

Reviews

Table of Contents

Excerpt

The gentleman’s suit is one of those overlooked but enduring symbols of modern civilization. For almost four hundred years it has been held up by artists, philosophers and critics as evidence of humanity’s unceasing and transformative search for perfection. Through its fitness for purpose, its sleek elegance and its social grace it has become a perfect example of evolutionary theory and democratic utopianism made material. The Viennese architect Adolf Loos, father of modernism and occasional fashion journalist, was one of those suitophiles for whom fine tailoring signified holiness. He wrote an influential series of short articles in the years around 1900 that positioned the bespoke and everyday objects of the contemporary gentleman’s wardrobe as archetypes of progressive design. Hats, shoes, underwear and accessories were scrutinized for the qualities that set them in competition with the inferior output of more ‘vulgar’ industrial sectors (women’s dress) and nations (Germany). For Loos the suit was a fundamental component of an enlightened existence, a signifier of civilization older in origination even than Laugier’s hut, that prehistoric model for the classical temple. The suit had seemingly always been there to remind man of the responsibilities and prizes attached to his higher state:

I have only praise for my clothes. They actually are the earliest human outfit. The materials are the same as the cloak that Wodin, the mythical Norse leader of the ‘wild hunt’[,] wore . . . It is mankind’s primeval dress . . . [It] can, regardless of the era and the area of the globe, cover the nakedness of the pauper without adding a foreign note to the time or the landscape . . . It has always been with us . . . It is the dress of those rich in spirit. It is the dress of the self-reliant. It is the attire of people whose individuality is so strong they cannot bring themselves to express it with the aid of garish colours, plumes or elaborate modes of dress. Woe to the painter expressing his individuality with a satin frock, for the artist in him has resigned in despair.

The earnest consideration of clothing by literary and artistic Vienna a century ago operated in an intellectual context far removed from the more superficial concerns of much early twenty-first-century celebrity- and brand-focused public fashion discourse. The social, economic and spatial circumstances in which clothes are made, sold, promoted and worn have also developed in myriad ways. But the suit itself, as worn and understood by Loos, survives in barely modified form as an item of everyday and formal wear in most regions of the world. Its apparent demise as a relevant component of work, leisured and ceremonial dress has been trumpeted by successive pundits, although its unobtrusive yet ubiquitous contours still furnish the bodies of men and women in all walks of life, from politicians to estate agents, bankers to rabbis, courtroom defendants to wedding grooms.

This book, in its tracing of the suit’s all-pervasive influence in modern and contemporary cultures, will attempt to do justice to Adolf Loos’s faith in his clothes; to show how the suit’s simple solutions have emerged and how its original meanings persist and adapt to denote truths that are greater than a basic meeting of cloth, scissors and thread. In order to do so, it will be necessary to start with the fundamentals, with the form of the suit itself.

Bespoke (fitted to the customer’s precise measurements and handmade locally by master craftsmen) or ready-to-wear (presized and mass-manufactured across a network of often distant factories by hand and machine), the suit as we know it now conforms to a basic two- or three-piece structure, generally made in finely woven wool or wool mix with a canvas, horsehair and cotton (or synthetic cotton) interlining to provide structure, and a silk or viscose lining. Its fabrics have always been an integral element of the suit’s appeal and an important marker of its quality. The selection of smooth worsteds, soft Saxonies and rough Cheviots, divided into standard baratheas, military Bedford cords, glossy broadcloths, sporting cavalry twills, workaday corduroys, elegant flannels, strong serges, hardy tweeds and homespuns, and dressy velvets, dictates the colour, texture, fit, handle and longevity of a suit, and is often the first consideration in the process of specification. The choice of weave and design – plain or Panama, hopsack or Celtic, diagonal, Mayo, Campbell or Russian twill, Bannockburn or pepper and salt, pinhead, birdseye, Eton stripe, barleycorn, herringbone, dogtooth, Glenurquhart or Prince of Wales check, pin- or chalkstripe – becomes the key to a customer’s character.

In made-up form, the suit is usually characterized by a longsleeved, buttoned jacket with lapels and pockets, a sleeveless waistcoat or vest worn underneath the jacket (if three-piece) and long trousers. The simplicity of its appearance is belied by the complexity of its construction, as a recent comparative study of ready-made suit manufacture commissioned by the British Government Department of Trade and Industry demonstrated:

A tailored jacket has an intricate structure, composed of as many as 40–50 components . . . Its manufacture may involve up to 75 separate operations. The first step in the production process is the ‘marker’ – a pattern according to which the many components . . . are cut from the material . . . The production sequence is, in principle, similar to making cars. The various parts are made first, they are then assembled into sub-assemblies, which are progressively brought together for final assembly. Smaller items are made . . . in parallel with the body fronts – interlinings, back sections, pockets, collars, sleeves, and sleeve linings. Pockets and interlinings are attached to the body front. Back sections are joined to the fronts, then collars. Sleeves are lined and then joined to the body. Buttonholes and buttons are added . . . A range of mechanical presses, each with a moulded shape, are used for top pressing the completed garment.

The analogy with the automated production-line processes of car manufacturing is, however, misleading. As the authors of the report go on to explain, the almost sensile, embodied nature of the product entails an attention to the idiosyncracies of the individual suit style, impossible to achieve through total mechanization:

The favoured approach is the ‘progressive bundle’ system, whereby all the parts needed to make a suit are bundled together, and are progressively assembled. Operators are grouped according to the section of the garment on which they work and the work is passed between them. The system has the flexibility to cope with variations between one suit and another, with training and absenteeism.

The contemporary ready-made suit, then, is the product of a widely recognized and well-ordered system of manufacture, refined and democratized throughout the twentieth century by high-street pioneers and international brands, and present in the wardrobes of many. Its bespoke variation continues to be manufactured on traditional lines, for an elite minority in the West and a wider audience in Asia and the developing world. Both options conform to an accepted set of parameters that produce a fairly standardized and familiar necessity, almost boring in the predictability of its form. But it was not always thus. When the proposition of a ‘suit’ of clothing (a well-fitted set of garments to be worn at the same time, although not necessarily of matching cloth) emerged in Europe’s cities and royal courts during the fourteenth century, its construction was more likely to constitute a complex negotiation between the skill of the tailor and other craftsmen and women, and the tastes and desires of the client. The possibilities for variation were endless.

Surviving letters of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries between members of the nobility and their agents who were procuring dress items for them in London and elsewhere, and early autobiographical accounts of sartorial choices, betray an intense consideration of several variables regarding price, quality of materials, detail of cut and construction, colour and adherence to notions of fashionableness, modesty and courtly style, all complicated by the more specialized circumstances of the clothing trades in this period. The commission of one ‘suit’ of clothes would involve transactions with several tradesmen, from the cloth merchant to the tailor, the button and buttonhole-makers, the embroiderer and so on.

I have only praise for my clothes. They actually are the earliest human outfit. The materials are the same as the cloak that Wodin, the mythical Norse leader of the ‘wild hunt’[,] wore . . . It is mankind’s primeval dress . . . [It] can, regardless of the era and the area of the globe, cover the nakedness of the pauper without adding a foreign note to the time or the landscape . . . It has always been with us . . . It is the dress of those rich in spirit. It is the dress of the self-reliant. It is the attire of people whose individuality is so strong they cannot bring themselves to express it with the aid of garish colours, plumes or elaborate modes of dress. Woe to the painter expressing his individuality with a satin frock, for the artist in him has resigned in despair.

The earnest consideration of clothing by literary and artistic Vienna a century ago operated in an intellectual context far removed from the more superficial concerns of much early twenty-first-century celebrity- and brand-focused public fashion discourse. The social, economic and spatial circumstances in which clothes are made, sold, promoted and worn have also developed in myriad ways. But the suit itself, as worn and understood by Loos, survives in barely modified form as an item of everyday and formal wear in most regions of the world. Its apparent demise as a relevant component of work, leisured and ceremonial dress has been trumpeted by successive pundits, although its unobtrusive yet ubiquitous contours still furnish the bodies of men and women in all walks of life, from politicians to estate agents, bankers to rabbis, courtroom defendants to wedding grooms.

This book, in its tracing of the suit’s all-pervasive influence in modern and contemporary cultures, will attempt to do justice to Adolf Loos’s faith in his clothes; to show how the suit’s simple solutions have emerged and how its original meanings persist and adapt to denote truths that are greater than a basic meeting of cloth, scissors and thread. In order to do so, it will be necessary to start with the fundamentals, with the form of the suit itself.

Bespoke (fitted to the customer’s precise measurements and handmade locally by master craftsmen) or ready-to-wear (presized and mass-manufactured across a network of often distant factories by hand and machine), the suit as we know it now conforms to a basic two- or three-piece structure, generally made in finely woven wool or wool mix with a canvas, horsehair and cotton (or synthetic cotton) interlining to provide structure, and a silk or viscose lining. Its fabrics have always been an integral element of the suit’s appeal and an important marker of its quality. The selection of smooth worsteds, soft Saxonies and rough Cheviots, divided into standard baratheas, military Bedford cords, glossy broadcloths, sporting cavalry twills, workaday corduroys, elegant flannels, strong serges, hardy tweeds and homespuns, and dressy velvets, dictates the colour, texture, fit, handle and longevity of a suit, and is often the first consideration in the process of specification. The choice of weave and design – plain or Panama, hopsack or Celtic, diagonal, Mayo, Campbell or Russian twill, Bannockburn or pepper and salt, pinhead, birdseye, Eton stripe, barleycorn, herringbone, dogtooth, Glenurquhart or Prince of Wales check, pin- or chalkstripe – becomes the key to a customer’s character.

In made-up form, the suit is usually characterized by a longsleeved, buttoned jacket with lapels and pockets, a sleeveless waistcoat or vest worn underneath the jacket (if three-piece) and long trousers. The simplicity of its appearance is belied by the complexity of its construction, as a recent comparative study of ready-made suit manufacture commissioned by the British Government Department of Trade and Industry demonstrated:

A tailored jacket has an intricate structure, composed of as many as 40–50 components . . . Its manufacture may involve up to 75 separate operations. The first step in the production process is the ‘marker’ – a pattern according to which the many components . . . are cut from the material . . . The production sequence is, in principle, similar to making cars. The various parts are made first, they are then assembled into sub-assemblies, which are progressively brought together for final assembly. Smaller items are made . . . in parallel with the body fronts – interlinings, back sections, pockets, collars, sleeves, and sleeve linings. Pockets and interlinings are attached to the body front. Back sections are joined to the fronts, then collars. Sleeves are lined and then joined to the body. Buttonholes and buttons are added . . . A range of mechanical presses, each with a moulded shape, are used for top pressing the completed garment.

The analogy with the automated production-line processes of car manufacturing is, however, misleading. As the authors of the report go on to explain, the almost sensile, embodied nature of the product entails an attention to the idiosyncracies of the individual suit style, impossible to achieve through total mechanization:

The favoured approach is the ‘progressive bundle’ system, whereby all the parts needed to make a suit are bundled together, and are progressively assembled. Operators are grouped according to the section of the garment on which they work and the work is passed between them. The system has the flexibility to cope with variations between one suit and another, with training and absenteeism.

The contemporary ready-made suit, then, is the product of a widely recognized and well-ordered system of manufacture, refined and democratized throughout the twentieth century by high-street pioneers and international brands, and present in the wardrobes of many. Its bespoke variation continues to be manufactured on traditional lines, for an elite minority in the West and a wider audience in Asia and the developing world. Both options conform to an accepted set of parameters that produce a fairly standardized and familiar necessity, almost boring in the predictability of its form. But it was not always thus. When the proposition of a ‘suit’ of clothing (a well-fitted set of garments to be worn at the same time, although not necessarily of matching cloth) emerged in Europe’s cities and royal courts during the fourteenth century, its construction was more likely to constitute a complex negotiation between the skill of the tailor and other craftsmen and women, and the tastes and desires of the client. The possibilities for variation were endless.

Surviving letters of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries between members of the nobility and their agents who were procuring dress items for them in London and elsewhere, and early autobiographical accounts of sartorial choices, betray an intense consideration of several variables regarding price, quality of materials, detail of cut and construction, colour and adherence to notions of fashionableness, modesty and courtly style, all complicated by the more specialized circumstances of the clothing trades in this period. The commission of one ‘suit’ of clothes would involve transactions with several tradesmen, from the cloth merchant to the tailor, the button and buttonhole-makers, the embroiderer and so on.