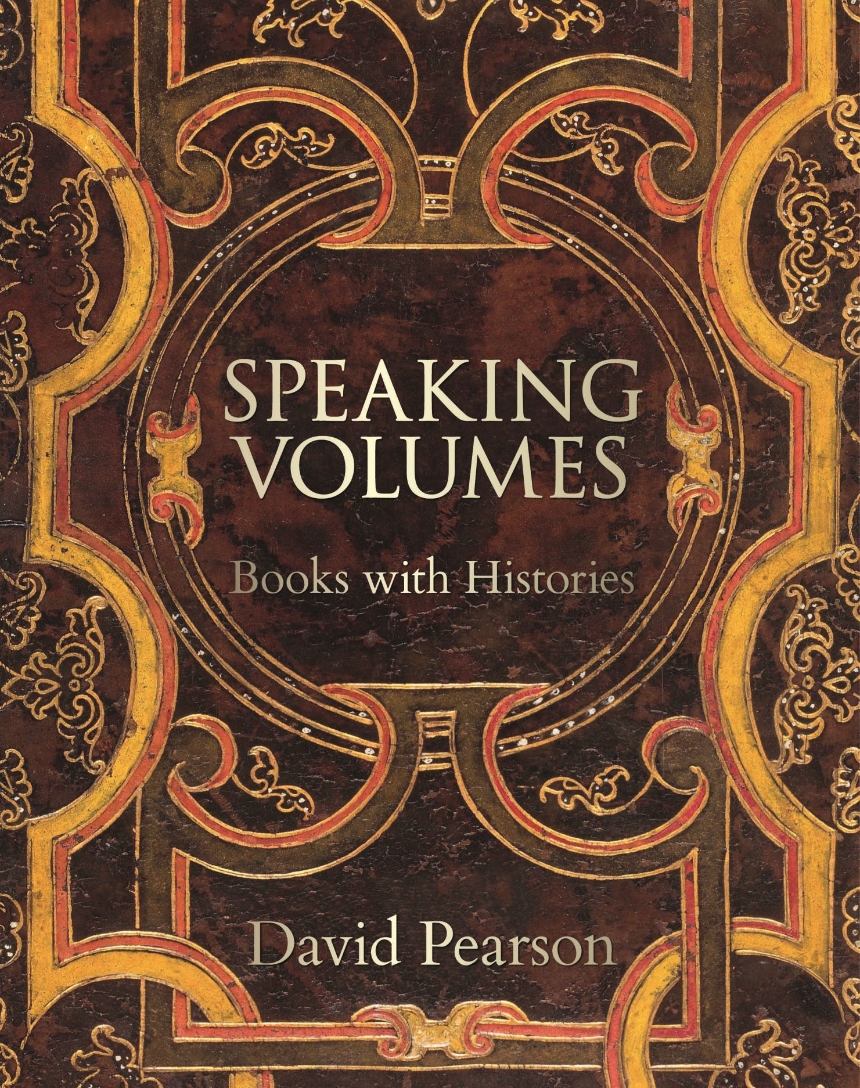

A fascinating catalog that analyzes books as historical objects.

Scholars increasingly recognize that the cultural and research value of books lies not just in their printed contents, but in their value as historical artifacts. An individual book can tell us many things about the ways books have been used, read, and regarded throughout the years.

Within these pages, you will find books damaged by bullets or graffiti, recovered from fire or water, or even disguised as completely different texts for protection in dangerous times. Marks of ownership—be it a rich treasure binding or a humble family inscription—shine a light on social history and literacy, while student doodles from the sixteenth century and a variety of pithy annotations give us a sense of readers through the ages.

Generously illustrated with examples from the early Middle Ages to the present day, Speaking Volumes presents a fascinating selection of books in both public and private collections whose individual histories tell surprising and illuminating stories, encouraging us to look at and appreciate books in new and non-traditional ways.

Scholars increasingly recognize that the cultural and research value of books lies not just in their printed contents, but in their value as historical artifacts. An individual book can tell us many things about the ways books have been used, read, and regarded throughout the years.

Within these pages, you will find books damaged by bullets or graffiti, recovered from fire or water, or even disguised as completely different texts for protection in dangerous times. Marks of ownership—be it a rich treasure binding or a humble family inscription—shine a light on social history and literacy, while student doodles from the sixteenth century and a variety of pithy annotations give us a sense of readers through the ages.

Generously illustrated with examples from the early Middle Ages to the present day, Speaking Volumes presents a fascinating selection of books in both public and private collections whose individual histories tell surprising and illuminating stories, encouraging us to look at and appreciate books in new and non-traditional ways.

240 pages | 180 color plates | 7 1/2 x 9 3/4 | © 2022

Culture Studies:

Guides, Manuals, and Reference: Books on Books

History: General History

Reviews

Table of Contents

Excerpt

This is a book about why books matter. It is not about why ideas, stories or knowledge matter – those things which are conveyed in books, and which are often what people mean when they use the word ‘books’ – but about the physical objects themselves. It is about asking a basic question which can be put to any book in front of you, whether it is a Shakespeare First Folio, an eighteenth-century book on gardening, a nineteenth-century novel, or this copy of this book: what is the cultural value of this object? What is it about this book – if anything – which makes it worth looking after for the benefit of the future? Is it a book whose loss to posterity would be an insignificant heartbeat in the endless cycle of human transactional affairs – briefly quarried by you, the reader, for some informational or recreational purpose before being discarded – or is it one which has lasting value not only for today, but also for tomorrow? If the latter, where does that value reside?

The belief that books do matter in this way is firmly ingrained in every literate human society, and it has created an infrastructure which we largely take for granted. Books are integrally connected with agendas for education and wellbeing, and a belief in the importance of ensuring access for everyone led to the development of public library networks from the late nineteenth century onwards. The idea that we need libraries as storehouses of knowledge is of course much older. That core function of books as containers of content that we might want to read both today and tomorrow, that can be organized and preserved so as to create ongoing access, has been respected for many centuries. The Library of Alexandria, founded around 300 bce, is famous as the greatest library of the classical world, holding the written output of those civilizations in maybe half a million scrolls, before war and political change brought about decline and destruction. It was, however, only one of many, and both public and private libraries were spread across the Roman Empire.

Across medieval Europe, libraries were widely established in universities, monasteries and other religious institutions, and although many of the latter were dispersed between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, many of those books came to be redistributed across a web of academic and national libraries whose steady growth has been part of our post-Reformation world. They may have reached their current homes via private hands – between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, many of the largest libraries belonged to individuals rather than institutions – but the nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw changing patterns, when a selling-off of family libraries was matched with huge investment in institutional ones. There are exceptions, but our landscape today is one where we have a worldwide framework of libraries, often in universities or major cities, all supported by public or charitable funding, where we have placed the responsibility for preserving and developing our documentary heritage. These are the libraries that we go to for serious work, that support higher-level education and industrial research, where we expect to find the rare and the special, the deep and rich seams of accumulated knowledge or ideas.

The founding rationale of all these libraries is summarized in the late-eighteenth-century image of ‘History resisting Time from destroying a Column of Books’. The record of the past – from Creation to the present time, as the engraving has it – is preserved in books and we are dependent on their survival for access to that heritage. If the books were lost – as Time, left to its own devices, would bring about – we would lose it all; our attempts to survey human history would face a blank wall. That idea has sustained, over many centuries, the ongoing development of great libraries, whose growth has transcended the merely functional. Many of them are housed in spaces whose elegance or imposing nature helps to reflect that critical importance, to inspire awe as well as respect, making them endlessly suitable for handsome illustrated books and calendars of the world’s great libraries. Duke Humfrey’s Library in Oxford is a much-loved example; every year, millions of people visit the Long Room in Trinity College, Dublin, or admire the painted cases and ceiling of the Vatican Library’s Sistine Hall. Great libraries play a variety of roles in today’s society, as vibrant cultural institutions supporting all kinds of education or events, but they are rooted in their huge collections. ‘How many books?’ is a vital statistic which will almost invariably be found on any research or national library website.

Looking at it from the opposite angle, the way to eradicate a civilization is to destroy its library and records, as the first Chinese emperor recognized in the third century bce when he ordered the burning of all historical books before his time, and the execution of scholars who might remember them. Over two millennia later, his successors undertook a similar exercise in Tibet, where it is estimated that 85 per cent of the written materials and documents were destroyed during purgation in the 1960s and 1970s. Modern times have seen many such incidents, including the destruction of the National Library of Cambodia in the 1970s by the Khmer Rouge, the shelling of the National Library of Bosnia-Herzegovina during the Siege of Sarajevo in 1992, and the partial burning of the manuscripts of the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu by an Islamist militia. The murder of Jewish people is the defining horror of the Holocaust, but it is less well known that one of its facets was an organized effort to gather up and destroy their archives and libraries across Europe. It has been estimated that over 100 million books were deliberately destroyed by the Nazis. At Sarajevo, where the library took three days to burn after being deliberately targeted with incendiary shells, around 2 million printed books and half a million metres of archives and manuscripts were lost, collections which had been carefully developed to constitute the memory and record of Bosnian culture.

There is no doubting, therefore, that we think books and libraries are important. I entirely agree with that, and my aim here is to widen our traditional ideas as to why they matter, and the answers to that question about cultural value.

The belief that books do matter in this way is firmly ingrained in every literate human society, and it has created an infrastructure which we largely take for granted. Books are integrally connected with agendas for education and wellbeing, and a belief in the importance of ensuring access for everyone led to the development of public library networks from the late nineteenth century onwards. The idea that we need libraries as storehouses of knowledge is of course much older. That core function of books as containers of content that we might want to read both today and tomorrow, that can be organized and preserved so as to create ongoing access, has been respected for many centuries. The Library of Alexandria, founded around 300 bce, is famous as the greatest library of the classical world, holding the written output of those civilizations in maybe half a million scrolls, before war and political change brought about decline and destruction. It was, however, only one of many, and both public and private libraries were spread across the Roman Empire.

Across medieval Europe, libraries were widely established in universities, monasteries and other religious institutions, and although many of the latter were dispersed between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, many of those books came to be redistributed across a web of academic and national libraries whose steady growth has been part of our post-Reformation world. They may have reached their current homes via private hands – between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, many of the largest libraries belonged to individuals rather than institutions – but the nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw changing patterns, when a selling-off of family libraries was matched with huge investment in institutional ones. There are exceptions, but our landscape today is one where we have a worldwide framework of libraries, often in universities or major cities, all supported by public or charitable funding, where we have placed the responsibility for preserving and developing our documentary heritage. These are the libraries that we go to for serious work, that support higher-level education and industrial research, where we expect to find the rare and the special, the deep and rich seams of accumulated knowledge or ideas.

The founding rationale of all these libraries is summarized in the late-eighteenth-century image of ‘History resisting Time from destroying a Column of Books’. The record of the past – from Creation to the present time, as the engraving has it – is preserved in books and we are dependent on their survival for access to that heritage. If the books were lost – as Time, left to its own devices, would bring about – we would lose it all; our attempts to survey human history would face a blank wall. That idea has sustained, over many centuries, the ongoing development of great libraries, whose growth has transcended the merely functional. Many of them are housed in spaces whose elegance or imposing nature helps to reflect that critical importance, to inspire awe as well as respect, making them endlessly suitable for handsome illustrated books and calendars of the world’s great libraries. Duke Humfrey’s Library in Oxford is a much-loved example; every year, millions of people visit the Long Room in Trinity College, Dublin, or admire the painted cases and ceiling of the Vatican Library’s Sistine Hall. Great libraries play a variety of roles in today’s society, as vibrant cultural institutions supporting all kinds of education or events, but they are rooted in their huge collections. ‘How many books?’ is a vital statistic which will almost invariably be found on any research or national library website.

Looking at it from the opposite angle, the way to eradicate a civilization is to destroy its library and records, as the first Chinese emperor recognized in the third century bce when he ordered the burning of all historical books before his time, and the execution of scholars who might remember them. Over two millennia later, his successors undertook a similar exercise in Tibet, where it is estimated that 85 per cent of the written materials and documents were destroyed during purgation in the 1960s and 1970s. Modern times have seen many such incidents, including the destruction of the National Library of Cambodia in the 1970s by the Khmer Rouge, the shelling of the National Library of Bosnia-Herzegovina during the Siege of Sarajevo in 1992, and the partial burning of the manuscripts of the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu by an Islamist militia. The murder of Jewish people is the defining horror of the Holocaust, but it is less well known that one of its facets was an organized effort to gather up and destroy their archives and libraries across Europe. It has been estimated that over 100 million books were deliberately destroyed by the Nazis. At Sarajevo, where the library took three days to burn after being deliberately targeted with incendiary shells, around 2 million printed books and half a million metres of archives and manuscripts were lost, collections which had been carefully developed to constitute the memory and record of Bosnian culture.

There is no doubting, therefore, that we think books and libraries are important. I entirely agree with that, and my aim here is to widen our traditional ideas as to why they matter, and the answers to that question about cultural value.