Distributed for Haus Publishing

The Serpent Coiled in Naples

A travelogue revealing the hidden stories of Naples.

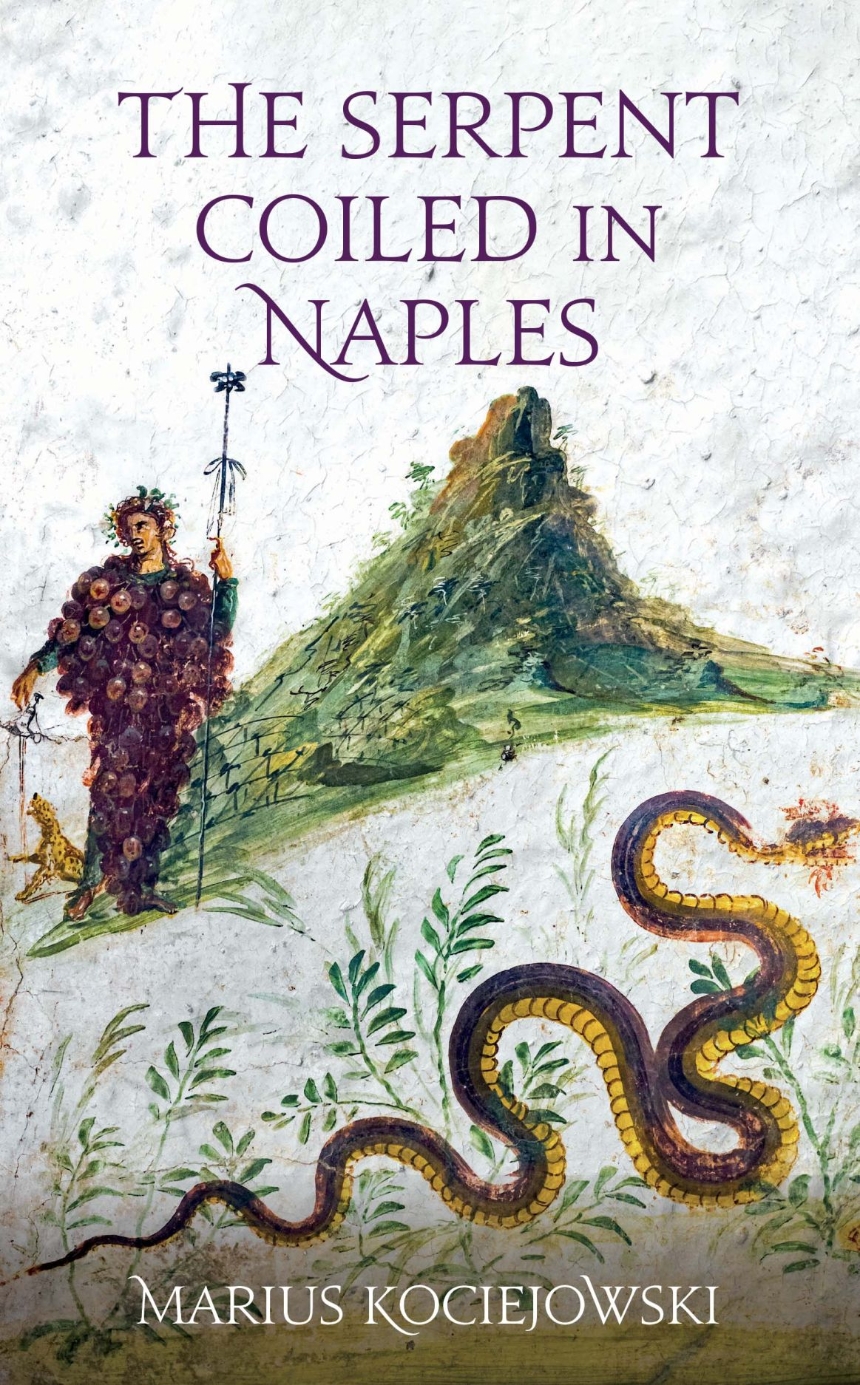

In recent years Naples has become, for better or worse, the new destination in Italy. While many of its more unusual features are on display for all to see, the stories behind them remain largely hidden. In Marius Kociejowski’s portrait of this baffling city, the serpent can be many things: Vesuvius, the mafia-like Camorra, the outlying Phlegrean Fields (which, geologically speaking, constitute the second most dangerous area on the planet). It is all these things that have, at one time or another, put paid to the higher aspirations of Neapolitans themselves. Naples is simultaneously the city of light, sometimes blindingly so, and the city of darkness, although often the stuff of cliché. The boundary that separates death from life is porous in the extreme: the dead inhabit the world of the living and vice versa. The Serpent Coiled in Naples is a travelogue, a meditation on mortality, and much else besides.

In recent years Naples has become, for better or worse, the new destination in Italy. While many of its more unusual features are on display for all to see, the stories behind them remain largely hidden. In Marius Kociejowski’s portrait of this baffling city, the serpent can be many things: Vesuvius, the mafia-like Camorra, the outlying Phlegrean Fields (which, geologically speaking, constitute the second most dangerous area on the planet). It is all these things that have, at one time or another, put paid to the higher aspirations of Neapolitans themselves. Naples is simultaneously the city of light, sometimes blindingly so, and the city of darkness, although often the stuff of cliché. The boundary that separates death from life is porous in the extreme: the dead inhabit the world of the living and vice versa. The Serpent Coiled in Naples is a travelogue, a meditation on mortality, and much else besides.

560 pages | 63 halftones | 5 x 7 3/4 | © 2022

Travel and Tourism: Tourism and History, Travel Writing and Guides

Reviews

Table of Contents

Contents

Chapter One

The Serpent Coiled in Naples

Chapter Two

An Octopus in Forcella

Chapter Three

Street of the Solitary Woman

Chapter Four

The Man Who Watches the Waters

Chapter Five

Street Music

Chapter Six

Leopardi’s Stomach

Chapter Seven

Raimondo di Sangro & the Veil of Knowledge

Chapter Eight

Old Bones

Chapter Nine

The Devil at Play in the Quartieri Spagnoli

Chapter Ten

Signor Volcano

Chapter Eleven

The Life and Death (and life) of Pulcinella

Chapter Twelve

Boom

Chapter Thirteen

The Intimate Lives of Things Inanimate

Chapter Fourteen

The Ghost Palace of Roberto De Simone

Chapter Fifteen

An Infinitesimal Particle of the Universe

Notes

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

The Serpent Coiled in Naples

Chapter Two

An Octopus in Forcella

Chapter Three

Street of the Solitary Woman

Chapter Four

The Man Who Watches the Waters

Chapter Five

Street Music

Chapter Six

Leopardi’s Stomach

Chapter Seven

Raimondo di Sangro & the Veil of Knowledge

Chapter Eight

Old Bones

Chapter Nine

The Devil at Play in the Quartieri Spagnoli

Chapter Ten

Signor Volcano

Chapter Eleven

The Life and Death (and life) of Pulcinella

Chapter Twelve

Boom

Chapter Thirteen

The Intimate Lives of Things Inanimate

Chapter Fourteen

The Ghost Palace of Roberto De Simone

Chapter Fifteen

An Infinitesimal Particle of the Universe

Notes

Acknowledgements

Excerpt

All over Naples I showed people a sentence that, for quick access, I wrote on the inside cover of my notebook, and which, if my source is correct, is a Sicilian proverb: ‘Mai temere Roma, il serpente se ne sta attorcigliato a Napoli’ (‘Never fear Rome, the serpent lies coiled in Naples’). Admittedly I seized upon the proverb before I ever got to Naples. It provided me with a title before I knew what the book’s contents would be. It was like being handed a physical law for which I had yet to find a theory, one that I’d make fit no matter what, there being something of the Jacopo in me. Would it be too much to say that by tenor alone the line carries its own inner truth? Sadly I’ve been unable to chase the serpent to its source, but then what makes a proverb a proverb is its anonymous nature and the way it has been polished by time. And then there’s the problem of how best to interpret it. Matthew 10:36 has been cited: ‘And a man’s foes shall be they of his own household.’ It’s what most gangsters learn by rote, but never fully absorb because sooner or later they make a mistake. The serpent for them tends to strike from within the family circle. There is, I think, even more juice to be squeezed from the pomegranate. The proverb seems to be loaded with metaphysical significance. What applies to Naples applies to the universe. Soon I began to see that serpent everywhere. I place the emphasis on attorcigliato, which means ‘twisted’ or ‘coiled’, a thing so tightly wound it might snap at any second, at which point it’s best not to be anywhere within striking range. Admittedly the serpent occupies but a tiny place in the city’s mythology and so while I do not want to push an image at the expense of veracity it serves as my personal take on the lives of the people I met there. So tightly wound are the hairsprings in their watches that a single turn more and all their best efforts come to naught. The Naples I have come to love breaks hearts.

What the sentence brought out in the Neapolitans I showed it to was, in the main, puzzlement or a shrug of the shoulders until finally one man roared with laughter, saying, ‘Yes, perfect! Very nice!’ Domenico Garofalo is a mover, a man who makes things happen. Certainly he has done his bit for culture, and, among other things, he is involved in organising festivals and contemporary dances, which was how I met him. I had lost my way in the Spanish Quarter when I stopped to ask for directions, and after giving them to me this friendly man in his early forties suggested I come back later for a performance he had organised at the theatre opposite the café where he was lording it over his coffee, as did Garrick in front of his theatre.

A couple of days later, I met him again in the quietest spot in Naples, the newly restored, staggeringly white, courtyard of the Convento di San Domenico Maggiore. Domenico’s enthusiasms took me in a hundred directions, from jazz and dance to a Neapolitan rap band called La Famiglia (in particular a song of theirs called ‘Odissea’, which compresses into five minutes the whole history of Naples beginning with ancient Parthenope), the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, the writings of Hegel (about which I know little, although I was made to understand Naples is a Hegelian place) and Blaise Pascal, and onwards to Giacomo Leopardi and Curzio Malaparte. There was no saying where next he’d take me. Willing to go high and low, eclectic by nature, Domenico was a most reliable guide. A few minutes later, in the Piazza del Gesù Nuovo, he pointed to the statue of the Virgin Mary on top of the baroque Obelisco dell’Immacolata. ‘Look,’ he cried, ‘there’s your creature!’ And indeed, beneath the foot of the Virgin, was a coiled serpent. Nothing so unusual in that, it being a common enough feature in Christian iconography, but I had been vindicated by the very best of authorities. She wouldn’t stand for any nonsense. Domenico invited me to look again at the statue and tell him what else I could see because it would bear on another matter we’d been discussing only minutes before, which had to do with the inextricable relationship in Naples between the living and the dead and how one might simultaneously inhabit both worlds. We’d agreed that any description of the city’s duality was best located there. We had spoken of skulls and of the people who adopt them, the cult of anime pezzentelle. What was I meant to be looking at? I squinted my eyes a little. All became clear when Domenico pointed it out to me. When viewed from the sunny side, so to speak, the front of the statue of the Virgin represents life, but when seen from the dark side, and with perhaps somewhat deliberate eyes, it becomes, especially at night, the Grim Reaper. It is an optical illusion and probably accidental, although there has been the suggestion it was so rigged by members of the Sanseverino family, whose noses were put out of joint when their palace was perforce turned into the church of Gesù Nuova as punishment for their having taken the wrong side in a political row. Whatever the case, the statue’s dualistic nature has entered the city’s folklore.

The folkloric: this, apparently, is where I’ve been required to take extra care. I had been warned by certain people solicitous of its reputation that I was to avoid any depiction of Naples as a folkloric city. A bit of me thinks this is a species of political correctness because while its inhabitants are quite right to avoid stereotypes of themselves, it does seem to me that there is nothing as purely illustrative of a people as its folklore. Or could it be that talk of the folkloric gets in the way of the actively folkloric, such that it becomes a species of embarrassment or, even worse, a call to arms? My solemn warners have a point. As soon as one summons the folkloric it dies. We have seen what happens when it is recruited for nationalistic causes.

What the sentence brought out in the Neapolitans I showed it to was, in the main, puzzlement or a shrug of the shoulders until finally one man roared with laughter, saying, ‘Yes, perfect! Very nice!’ Domenico Garofalo is a mover, a man who makes things happen. Certainly he has done his bit for culture, and, among other things, he is involved in organising festivals and contemporary dances, which was how I met him. I had lost my way in the Spanish Quarter when I stopped to ask for directions, and after giving them to me this friendly man in his early forties suggested I come back later for a performance he had organised at the theatre opposite the café where he was lording it over his coffee, as did Garrick in front of his theatre.

A couple of days later, I met him again in the quietest spot in Naples, the newly restored, staggeringly white, courtyard of the Convento di San Domenico Maggiore. Domenico’s enthusiasms took me in a hundred directions, from jazz and dance to a Neapolitan rap band called La Famiglia (in particular a song of theirs called ‘Odissea’, which compresses into five minutes the whole history of Naples beginning with ancient Parthenope), the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, the writings of Hegel (about which I know little, although I was made to understand Naples is a Hegelian place) and Blaise Pascal, and onwards to Giacomo Leopardi and Curzio Malaparte. There was no saying where next he’d take me. Willing to go high and low, eclectic by nature, Domenico was a most reliable guide. A few minutes later, in the Piazza del Gesù Nuovo, he pointed to the statue of the Virgin Mary on top of the baroque Obelisco dell’Immacolata. ‘Look,’ he cried, ‘there’s your creature!’ And indeed, beneath the foot of the Virgin, was a coiled serpent. Nothing so unusual in that, it being a common enough feature in Christian iconography, but I had been vindicated by the very best of authorities. She wouldn’t stand for any nonsense. Domenico invited me to look again at the statue and tell him what else I could see because it would bear on another matter we’d been discussing only minutes before, which had to do with the inextricable relationship in Naples between the living and the dead and how one might simultaneously inhabit both worlds. We’d agreed that any description of the city’s duality was best located there. We had spoken of skulls and of the people who adopt them, the cult of anime pezzentelle. What was I meant to be looking at? I squinted my eyes a little. All became clear when Domenico pointed it out to me. When viewed from the sunny side, so to speak, the front of the statue of the Virgin represents life, but when seen from the dark side, and with perhaps somewhat deliberate eyes, it becomes, especially at night, the Grim Reaper. It is an optical illusion and probably accidental, although there has been the suggestion it was so rigged by members of the Sanseverino family, whose noses were put out of joint when their palace was perforce turned into the church of Gesù Nuova as punishment for their having taken the wrong side in a political row. Whatever the case, the statue’s dualistic nature has entered the city’s folklore.

The folkloric: this, apparently, is where I’ve been required to take extra care. I had been warned by certain people solicitous of its reputation that I was to avoid any depiction of Naples as a folkloric city. A bit of me thinks this is a species of political correctness because while its inhabitants are quite right to avoid stereotypes of themselves, it does seem to me that there is nothing as purely illustrative of a people as its folklore. Or could it be that talk of the folkloric gets in the way of the actively folkloric, such that it becomes a species of embarrassment or, even worse, a call to arms? My solemn warners have a point. As soon as one summons the folkloric it dies. We have seen what happens when it is recruited for nationalistic causes.