Distributed for University College Dublin Press

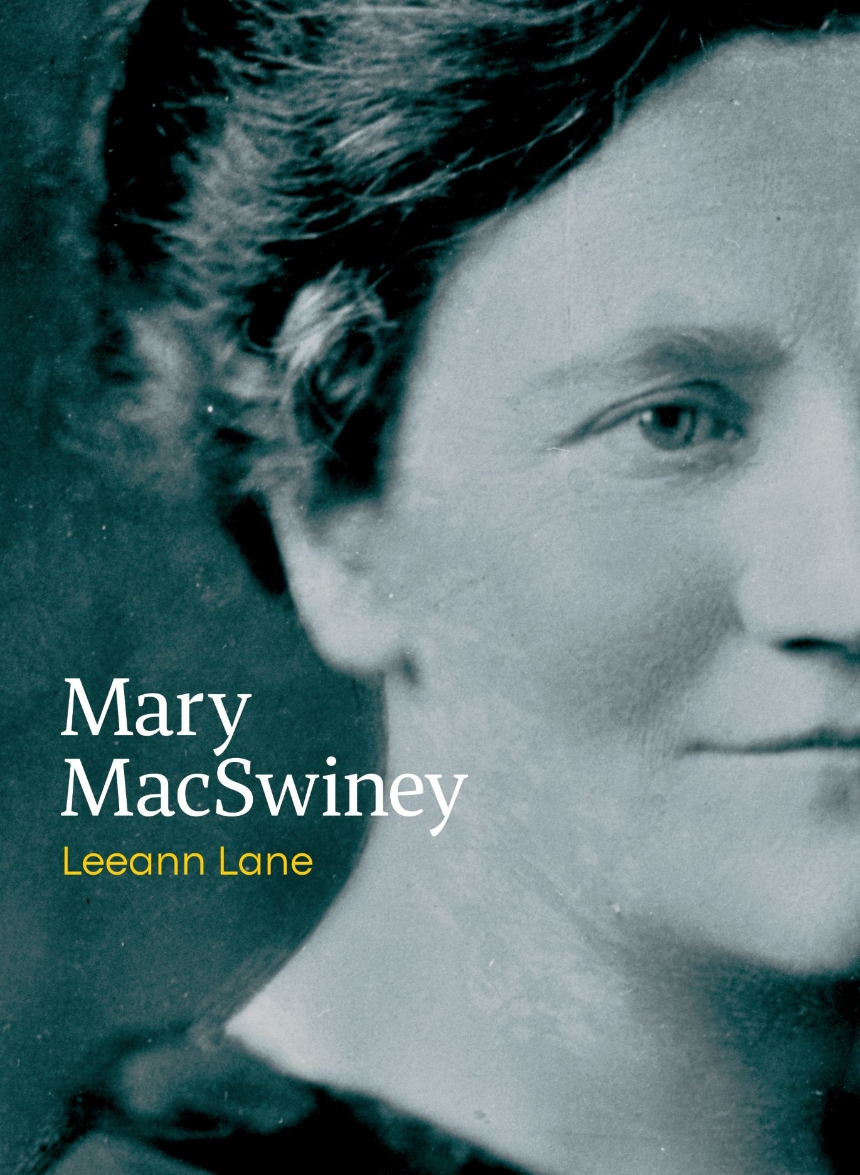

Mary MacSwiney

Leading biographer of women in Irish history Leeann Lane delves into newly discovered material across archives to tell Mary MacSwiney’s story.

Until now, an in-depth analysis of any female figures in Irish republicanism in the early twentieth century has been limited. Mary MacSwiney was one of the most single-minded anti-Treaty women, leading Eamon de Valera to describe her as “incorrigible.” Rather than dismiss MacSwiney as one-dimensional in her opposition to the Treaty and in her continued political intractability, this biography places her story at the center of the narrative to understand why she was increasingly viewed as a virago.

To say contemporary gender roles played a part in reducing MacSwiney to a cipher for extreme republicanism is only part of the story. Her uncompromising stance against the evils of compromise during the Treaty negotiations was indelibly formed by the experience of watching her brother Terence MacSwiney die on a hunger strike in 1920 and the trauma that resulted from it. Witnessing this intimate act of self-sacrifice bound her to a belief that her task was to continue her brother’s fidelity to a separatist republic. Betrayal of the republic, for her, would have meant betrayal of a brother she loved and admired.

Mary MacSwiney situates this standout figure in the context of her tightly knit family, tracing her political evolution from suffrage and cultural revival activism to advanced nationalism. At the same time, the focus of MacSwiney’s early activism was Cork, from 1920 onwards she began to assume a progressively more important role in Irish politics at a national and international level, including American tours, her central role during the Civil War, and within Sinn Féin and a political relationship with de Valera. From 1926 onward, she was increasingly politically isolated and marginalized as she sparred with members of Fianna Fáil in the press, seeking to justify her stance.

Leeann Lane interrogates an oppositional stance to Irish parliamentary politics in the later 1920s and 1930s, offering an essential read for anyone who wants to uncover a new side of this historical period from the perspective of the women who were all too often pushed to the margins of the fight.

Until now, an in-depth analysis of any female figures in Irish republicanism in the early twentieth century has been limited. Mary MacSwiney was one of the most single-minded anti-Treaty women, leading Eamon de Valera to describe her as “incorrigible.” Rather than dismiss MacSwiney as one-dimensional in her opposition to the Treaty and in her continued political intractability, this biography places her story at the center of the narrative to understand why she was increasingly viewed as a virago.

To say contemporary gender roles played a part in reducing MacSwiney to a cipher for extreme republicanism is only part of the story. Her uncompromising stance against the evils of compromise during the Treaty negotiations was indelibly formed by the experience of watching her brother Terence MacSwiney die on a hunger strike in 1920 and the trauma that resulted from it. Witnessing this intimate act of self-sacrifice bound her to a belief that her task was to continue her brother’s fidelity to a separatist republic. Betrayal of the republic, for her, would have meant betrayal of a brother she loved and admired.

Mary MacSwiney situates this standout figure in the context of her tightly knit family, tracing her political evolution from suffrage and cultural revival activism to advanced nationalism. At the same time, the focus of MacSwiney’s early activism was Cork, from 1920 onwards she began to assume a progressively more important role in Irish politics at a national and international level, including American tours, her central role during the Civil War, and within Sinn Féin and a political relationship with de Valera. From 1926 onward, she was increasingly politically isolated and marginalized as she sparred with members of Fianna Fáil in the press, seeking to justify her stance.

Leeann Lane interrogates an oppositional stance to Irish parliamentary politics in the later 1920s and 1930s, offering an essential read for anyone who wants to uncover a new side of this historical period from the perspective of the women who were all too often pushed to the margins of the fight.

Table of Contents

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Chapter 1 A Republican Family Unit

Chapter 2 Cork: 1916

Chapter 3 Cork: May 1916- August 1920

Chapter 4 1920: Trauma and the Brixton Hunger Strike, 1920

Chapter 5 America: December 1920-August 1921

Chapter 6 Truce to Treaty Split

Chapter 7 The Civil War

Chapter 8 Disillusionment: 1923-1926

Chapter 9 ‘Holding the Republican Fort’[1]: 1926-1942

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Chapter 1 A Republican Family Unit

Chapter 2 Cork: 1916

Chapter 3 Cork: May 1916- August 1920

Chapter 4 1920: Trauma and the Brixton Hunger Strike, 1920

Chapter 5 America: December 1920-August 1921

Chapter 6 Truce to Treaty Split

Chapter 7 The Civil War

Chapter 8 Disillusionment: 1923-1926

Chapter 9 ‘Holding the Republican Fort’[1]: 1926-1942

Bibliography

Index