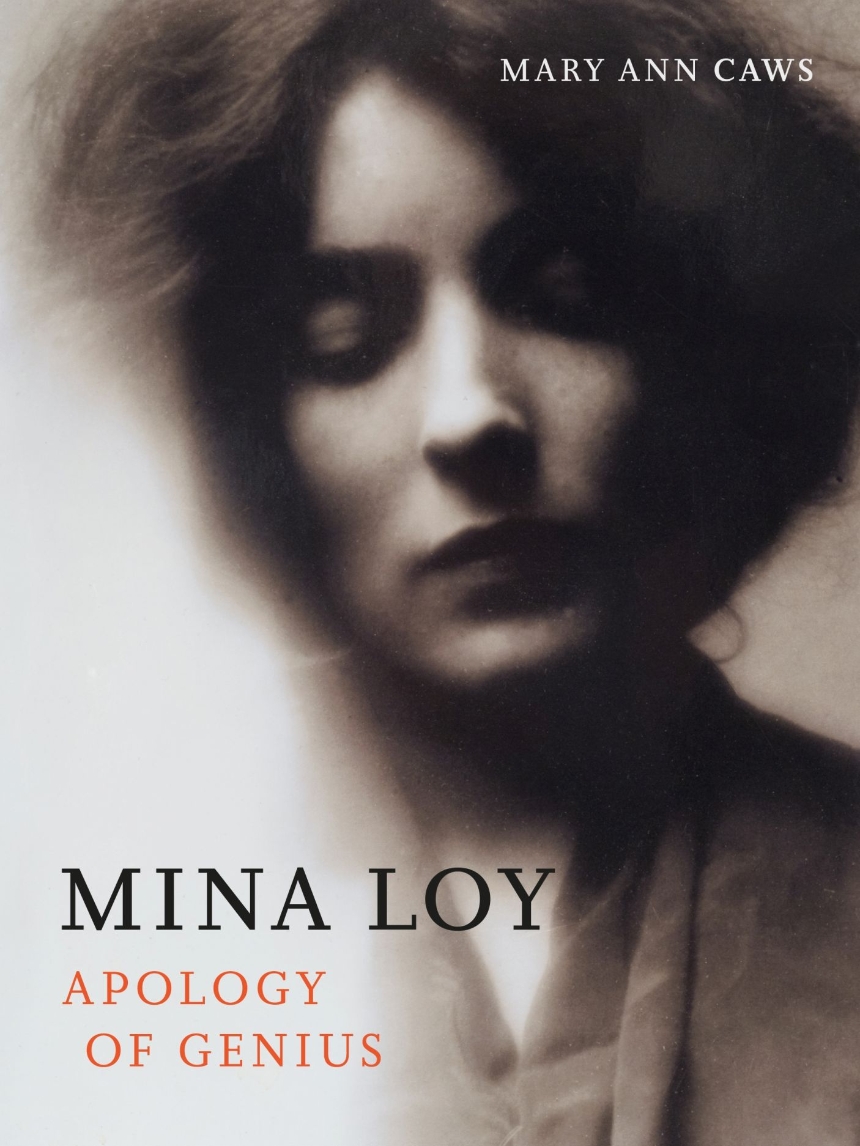

Featuring many rare images, an enlightening exploration of the life and work of avant-garde multihyphenate Mina Loy.

Mina Loy was born in London in 1882, became American, and lived variously in New York, Europe, and finally, Aspen until she died in 1966. Flamboyant and unapologetically avant-garde, she was a poet, painter, novelist, essayist, manifesto-writer, actress, and dress and lampshade designer. Her life involved an impossible abundance of artistic friends, performance, and spectacular adventures in the worlds of Futurism, Christian Science, feminism, fashion, and everything modern and modernist.

This new account by Mary Ann Caws explores Mina Loy’s exceptional life and features many rare images of Mina Loy and her husband, the Swiss writer, poet, artist, boxer, and provocateur Arthur Cravan—who disappeared without a trace in 1918.

Mina Loy was born in London in 1882, became American, and lived variously in New York, Europe, and finally, Aspen until she died in 1966. Flamboyant and unapologetically avant-garde, she was a poet, painter, novelist, essayist, manifesto-writer, actress, and dress and lampshade designer. Her life involved an impossible abundance of artistic friends, performance, and spectacular adventures in the worlds of Futurism, Christian Science, feminism, fashion, and everything modern and modernist.

This new account by Mary Ann Caws explores Mina Loy’s exceptional life and features many rare images of Mina Loy and her husband, the Swiss writer, poet, artist, boxer, and provocateur Arthur Cravan—who disappeared without a trace in 1918.

Reviews

Excerpt

INTRODUCTION:

WHY MINA LOY NOW?

Mina Loy the painter and poet was desperately, irretrievably and movingly modern. She performed in her prose, both theoretical and autobiographical, and her poems, an astonishingly complex mingling of the mental, the physical and the scientific, the most forward-looking feats imaginable. Her various forms of art, from the decorative to the painterly and abstract, spread out over places and genres both expected and unlikely. All through her life and its ventures, Mina Loy knew how to craft a singular and object-filled life. She was in one person a multi-flavourful assortment, a highly colourful modernist being.

After attending art school for the first time in London, she moved to another in Munich, and then to Paris, where she and a friend attended the Académie Colarossi at 10, rue de la Grande Chaumière, studying under Whistler. In a night class in drawing, she met the photographer and artist Stephen Haweis, who became her first husband and the father of a child who died very early on. Recovering from that loss, Mina was helped by a kindly and elegant physician, Dr Henri Joël Le Savoureux (delightful name– who was, alas, engaged to another), with whom she had her daughter Joella. Stephen was eager to move to Florence; there, in a grand villa just outside the city in Arcetri, lived the larger-than-life personality Mabel Dodge, an American hostess on a grand scale, then patroness of the Armory Show and columnist for the Hearst organization. Through Mabel Dodge, Mina met the editor Carl Van Vechten, a more than problematic character who was constantly helpful to her writings, and Gertrude Stein, about whom Mina wrote several times. She read a poem entitled ‘Gertrude Stein’ (originally published in the TransatlanticReview in 1924), calling her the ‘Madam Curie of language’, at Natalie Barney’s famous Temple de l’Amitié at 20 rue Jacob. The famous and beautiful lesbian writer presided over this salon in her white dresses with her golden-blonde hair, a ladykiller supreme. There Mina also met the painter Frances Simpson Stevens, with whom she encountered the Futurists in Florence and Milan. She rapidly became involved with both the colourful and stagey Milanese Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and the more traditional Florentine Giovanni Papini.

After leaving Florence and her Futurist life, Mina Loy left for New York, where her friend Frances Simpson Stevens helped her settle and introduced her to the Arensberg Circle. In Walter and Louise Arensberg’s duplex apartment at 3 West 67th Street she was to encounter the proto-Dada Arthur Cravan, whom she had seen at the opening of the Society of Independent Artists Exhibition on 18 April 1917 at Grand Central Palace, where her painting Making Lampshades was exhibited. The next day Cravan was to lecture there on ‘The Independent Artists of France and America’, but arrived drunk, thanks to the ministrations of Picabia and Duchamp preceding the performance. Thereupon he removed his coat, waistcoat, collar and braces, began to shout obscenities and was hauled off to a police station. On 25 May Mina and Cravan attended the Blindman’s Ball in Webster Hall, and the next day he gave a lecture and disrobed, as he had done previously.

In keeping with his frequent travelling habits, Cravan left New York, deluging Mina with letters from elsewhere, and then journeyed to Mexico to teach boxing. He wrote from there in December to beg her to join him, which she did. There they married and wandered around, poverty-stricken; they planned to escape from the port Salina Cruz to Argentina, hoping for better times. Mina was to leave on a passenger ship for Buenos Aires, and Cravan was trying out a small boat heading for Puerto Angel. But he never returned to Salina Cruz.

There are many stories about his mysterious disappearance, all of which position him as the diametrical opposite of Haweis, Mina’s first husband. One absolute fact is that he was the nephew of Oscar Wilde, as whom he liked posing and about whom he tells a grand and impossible tale of a visit: ‘Oscar Wilde est vivant!’ Another sure thing is that he was Mina’s passionately adored lover and second husband, her ‘Colossus’, the father of her daughter Fabienne, after his birth name: Fabian Lloyd. He was the editor and author of many parts of the six numbers of the splendidly peculiar literary review Maintenant, and was himself a bizarre compilation of boxer, writer, editor and a number of other occupations, before his mysterious and much-discussed appearances and disappearance. He was spectacular in every imaginable way and some that are unimaginable.

This was Mina’s lifelong loss. She was, after this Dada encounter, no less a Surrealist personality, unfixed in place between Paris and London and New York again; finally she lived in Aspen, Colorado, with Joella and Fabienne, where I went to follow in her tracks. Most interesting to me, apart from the zigzags of places in which she lived and the so variously motivated and arrayed personalities with whom she was involved from near or far during her lifetime, are her poems. She claimed not to be a poet – why is anyone taking an interest in my poems?, she queried, and indeed for a very long period wrote none at all – but I found her poems mesmerizingly present. They instigated the present book from the beginning, informing its various parts, interweaving with her life as much in their texture as in their envisioning of all her twists and turns from Futurism to Dada, Surrealism and Christian Science.

Ezra Pound, the premiere of whose opera The Testament of Villon Mina Loy attended in 1926, claimed that it was her ‘logo-poeic’ handling of abstract vocabulary that made her satirical style so distinctive. Most arresting among so many other facets of her poems is the way in which the various beads of elements in them – whether early and satirical or later and impassioned in their details and overall ideas – glitter and often oddly find themselves next to each other. We are often uncomfortable making our way between them, and seldom is there an overall impression: we are left suspended. I find this especially captivating in the reams of unfinished, incomplete poetic texts she left behind, many of which are gathered in the Beinecke Library at Yale, together with the abundant prose. For this reason, among others, my writing will focus mainly on her poetic texts, in poems and in prose. This book will not address her artwork, except in passing. A serious study of Mina Loy the artist is long overdue. An exhibition scheduled to open at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in 2023 will mark the first serious attempt to address this long-neglected subject.

Why is she so often compared to Marianne Moore, who to me seems so very different? Moore’s control of the text does not make me uncomfortable – she feels in charge. And I think I know where she is going, and I can go along or not. With Mina Loy I am never sure where she is or isn’t going, and don’t really feel either invited or excluded: I am not sure she knows I am there. These separate spectacular gems have no concern for the reader. Easier by far is the identification of various personalities in her text, such as the Futurists she was involved with, the explosive and colourful Filippo Tommaso Marinetti of Milan, or the far less dramatic and scene-conscious Florentine Giovanni Papini: one can often recognize these figures in the titles of the texts. Mina herself is recognizable only in her brilliant variousness. Tara Prescott found her work ‘layered and confounding’. Of herself, Mina Loy said: ‘Speak-easy? Why, if I ever tried to speak easily some policeman would come up and give me a really hard sentence!’

She perfectly suited her times, as did her costumes. Magically, she made an instantaneous, intuitive adjustment to whatever situation she inhabited. This is in no way to suggest that, living in the Lower East Side of New York City, mingling with the Bowery bums who took to her as she did to them, she would always wear shabby clothing. True, she ended by wearing her nightgown outdoors to appear with them, and they always found her saintly, no matter what clothes she appeared in. Her very changeability suited her well. We, her readers and very much aftercomers, can follow her from the early garb to the later, and from her early art in its peculiar Mannerist and Gothic mode, and her poetry from its early stages, its mockeries and flounces, through the salon conversational mode, to the Cravan-oriented lamenting and wandering modalities and the Bowery musings on the angelic bums, and on to the mental-metaphysical Christian Science texts, and the intermingling with Joseph Cornell boxes and arrangements, and her own pre-Schwitters constructions from found objects.

WHY MINA LOY NOW?

Mina Loy the painter and poet was desperately, irretrievably and movingly modern. She performed in her prose, both theoretical and autobiographical, and her poems, an astonishingly complex mingling of the mental, the physical and the scientific, the most forward-looking feats imaginable. Her various forms of art, from the decorative to the painterly and abstract, spread out over places and genres both expected and unlikely. All through her life and its ventures, Mina Loy knew how to craft a singular and object-filled life. She was in one person a multi-flavourful assortment, a highly colourful modernist being.

After attending art school for the first time in London, she moved to another in Munich, and then to Paris, where she and a friend attended the Académie Colarossi at 10, rue de la Grande Chaumière, studying under Whistler. In a night class in drawing, she met the photographer and artist Stephen Haweis, who became her first husband and the father of a child who died very early on. Recovering from that loss, Mina was helped by a kindly and elegant physician, Dr Henri Joël Le Savoureux (delightful name– who was, alas, engaged to another), with whom she had her daughter Joella. Stephen was eager to move to Florence; there, in a grand villa just outside the city in Arcetri, lived the larger-than-life personality Mabel Dodge, an American hostess on a grand scale, then patroness of the Armory Show and columnist for the Hearst organization. Through Mabel Dodge, Mina met the editor Carl Van Vechten, a more than problematic character who was constantly helpful to her writings, and Gertrude Stein, about whom Mina wrote several times. She read a poem entitled ‘Gertrude Stein’ (originally published in the TransatlanticReview in 1924), calling her the ‘Madam Curie of language’, at Natalie Barney’s famous Temple de l’Amitié at 20 rue Jacob. The famous and beautiful lesbian writer presided over this salon in her white dresses with her golden-blonde hair, a ladykiller supreme. There Mina also met the painter Frances Simpson Stevens, with whom she encountered the Futurists in Florence and Milan. She rapidly became involved with both the colourful and stagey Milanese Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and the more traditional Florentine Giovanni Papini.

After leaving Florence and her Futurist life, Mina Loy left for New York, where her friend Frances Simpson Stevens helped her settle and introduced her to the Arensberg Circle. In Walter and Louise Arensberg’s duplex apartment at 3 West 67th Street she was to encounter the proto-Dada Arthur Cravan, whom she had seen at the opening of the Society of Independent Artists Exhibition on 18 April 1917 at Grand Central Palace, where her painting Making Lampshades was exhibited. The next day Cravan was to lecture there on ‘The Independent Artists of France and America’, but arrived drunk, thanks to the ministrations of Picabia and Duchamp preceding the performance. Thereupon he removed his coat, waistcoat, collar and braces, began to shout obscenities and was hauled off to a police station. On 25 May Mina and Cravan attended the Blindman’s Ball in Webster Hall, and the next day he gave a lecture and disrobed, as he had done previously.

In keeping with his frequent travelling habits, Cravan left New York, deluging Mina with letters from elsewhere, and then journeyed to Mexico to teach boxing. He wrote from there in December to beg her to join him, which she did. There they married and wandered around, poverty-stricken; they planned to escape from the port Salina Cruz to Argentina, hoping for better times. Mina was to leave on a passenger ship for Buenos Aires, and Cravan was trying out a small boat heading for Puerto Angel. But he never returned to Salina Cruz.

There are many stories about his mysterious disappearance, all of which position him as the diametrical opposite of Haweis, Mina’s first husband. One absolute fact is that he was the nephew of Oscar Wilde, as whom he liked posing and about whom he tells a grand and impossible tale of a visit: ‘Oscar Wilde est vivant!’ Another sure thing is that he was Mina’s passionately adored lover and second husband, her ‘Colossus’, the father of her daughter Fabienne, after his birth name: Fabian Lloyd. He was the editor and author of many parts of the six numbers of the splendidly peculiar literary review Maintenant, and was himself a bizarre compilation of boxer, writer, editor and a number of other occupations, before his mysterious and much-discussed appearances and disappearance. He was spectacular in every imaginable way and some that are unimaginable.

This was Mina’s lifelong loss. She was, after this Dada encounter, no less a Surrealist personality, unfixed in place between Paris and London and New York again; finally she lived in Aspen, Colorado, with Joella and Fabienne, where I went to follow in her tracks. Most interesting to me, apart from the zigzags of places in which she lived and the so variously motivated and arrayed personalities with whom she was involved from near or far during her lifetime, are her poems. She claimed not to be a poet – why is anyone taking an interest in my poems?, she queried, and indeed for a very long period wrote none at all – but I found her poems mesmerizingly present. They instigated the present book from the beginning, informing its various parts, interweaving with her life as much in their texture as in their envisioning of all her twists and turns from Futurism to Dada, Surrealism and Christian Science.

Ezra Pound, the premiere of whose opera The Testament of Villon Mina Loy attended in 1926, claimed that it was her ‘logo-poeic’ handling of abstract vocabulary that made her satirical style so distinctive. Most arresting among so many other facets of her poems is the way in which the various beads of elements in them – whether early and satirical or later and impassioned in their details and overall ideas – glitter and often oddly find themselves next to each other. We are often uncomfortable making our way between them, and seldom is there an overall impression: we are left suspended. I find this especially captivating in the reams of unfinished, incomplete poetic texts she left behind, many of which are gathered in the Beinecke Library at Yale, together with the abundant prose. For this reason, among others, my writing will focus mainly on her poetic texts, in poems and in prose. This book will not address her artwork, except in passing. A serious study of Mina Loy the artist is long overdue. An exhibition scheduled to open at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in 2023 will mark the first serious attempt to address this long-neglected subject.

Why is she so often compared to Marianne Moore, who to me seems so very different? Moore’s control of the text does not make me uncomfortable – she feels in charge. And I think I know where she is going, and I can go along or not. With Mina Loy I am never sure where she is or isn’t going, and don’t really feel either invited or excluded: I am not sure she knows I am there. These separate spectacular gems have no concern for the reader. Easier by far is the identification of various personalities in her text, such as the Futurists she was involved with, the explosive and colourful Filippo Tommaso Marinetti of Milan, or the far less dramatic and scene-conscious Florentine Giovanni Papini: one can often recognize these figures in the titles of the texts. Mina herself is recognizable only in her brilliant variousness. Tara Prescott found her work ‘layered and confounding’. Of herself, Mina Loy said: ‘Speak-easy? Why, if I ever tried to speak easily some policeman would come up and give me a really hard sentence!’

She perfectly suited her times, as did her costumes. Magically, she made an instantaneous, intuitive adjustment to whatever situation she inhabited. This is in no way to suggest that, living in the Lower East Side of New York City, mingling with the Bowery bums who took to her as she did to them, she would always wear shabby clothing. True, she ended by wearing her nightgown outdoors to appear with them, and they always found her saintly, no matter what clothes she appeared in. Her very changeability suited her well. We, her readers and very much aftercomers, can follow her from the early garb to the later, and from her early art in its peculiar Mannerist and Gothic mode, and her poetry from its early stages, its mockeries and flounces, through the salon conversational mode, to the Cravan-oriented lamenting and wandering modalities and the Bowery musings on the angelic bums, and on to the mental-metaphysical Christian Science texts, and the intermingling with Joseph Cornell boxes and arrangements, and her own pre-Schwitters constructions from found objects.