Distributed for Reaktion Books

The Invention of Oscar Wilde

“One should either wear a work of art, or be a work of art,” Oscar Wilde once declared. In The Invention of Oscar Wilde, Nicholas Frankel explores Wilde’s self-creation as a “work of art” and a carefully constructed cultural icon. Frankel takes readers on a journey through Wilde’s inventive, provocative life, from his Irish origins—and their public erasure—through his challenges to traditional concepts of masculinity and male sexuality, his marriage and his affairs with young men, including his great love Lord Alfred Douglas, to his criminal conviction and final years of exile in France. Along the way, Frankel takes a deep look at Wilde’s writings, paradoxical wit, and intellectual convictions.

Reviews

Excerpt

'I have put my talent into my works, but I have put all my genius into my life,’ Wilde told his friend André Gide. To be sure, Wilde put his genius into his written works as well. Today his plays are among the wittiest and most frequently performed in the English stage repertoire, and together with his stories, essays, dialogues and poems, they helped bring down the curtain on an outmoded Victorianism.

But if Wilde gave rein to his imagination in his works, his invention and commitment to art were such that his life now reads like the greatest of his works. One should either wear a work of art or be a work of art, he declared. As we shall see, even as a young man he was determined to approach life on his own terms, and he remained an antinomian till his dying day, seizing at experience and unsettling the preconceptions of his fellow Victorians. In what he said and did – and even in the way he dressed, no less than in what he wrote – his life embodied a provocation and a rebuke to the pious conformism, cruelty and hypocrisy of Victorian England. Indeed he was never at home in England, where he spent the most successful years (1874–95) of his life and where he was always viewed as a rare exotic. Born in Ireland in 1854, he found the more open, tolerant atmosphere of France and the United States more conducive to his temper and sexuality, and he vowed to take up citizenship in France long before his final exile there following his release from an English prison in 1897.

If he was always at odds with England, however, he nevertheless lived among the English with rare passion, conviction and imagination, treating life as if it were the greatest of all arts. He was determined to put into practice Walter Pater’s injunction that ‘to burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life’. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, he called for a new spirituality of the senses; and like the eponymous hero of his own novel, Wilde’s object was nothing less than ‘to recreate life, and . . . save it from . . . harsh, uncomely puritanism’. Imprisoned for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895, he famously said that the company of male sex workers and blackmailers was like ‘feasting with panthers. The danger was half the excitement,’ and he emerged from prison under the pseudonym Sebastian Melmoth more determined than ever to follow his own path. It has been said that in his plays and stories Wilde dramatized the emergence of what the Situationist philosopher Guy Debord called a ‘society of the spectacle’, a world of conspicuous material consumption in which even language operates like a commodity or visual fetish. But Wilde’s greatest spectacle was himself: renowned in his own day for his sparkling conversation and wit no less than for his impeccable grooming and couture, he lived with self-conscious deliberateness and flamboyance – a living paradox, at once a creature of this world and apart from it. And if his written works stand in judgement on Victorian England, heralding the modern period that he helped bring into being, so too does Wilde’s uncompromising and novelistic life.

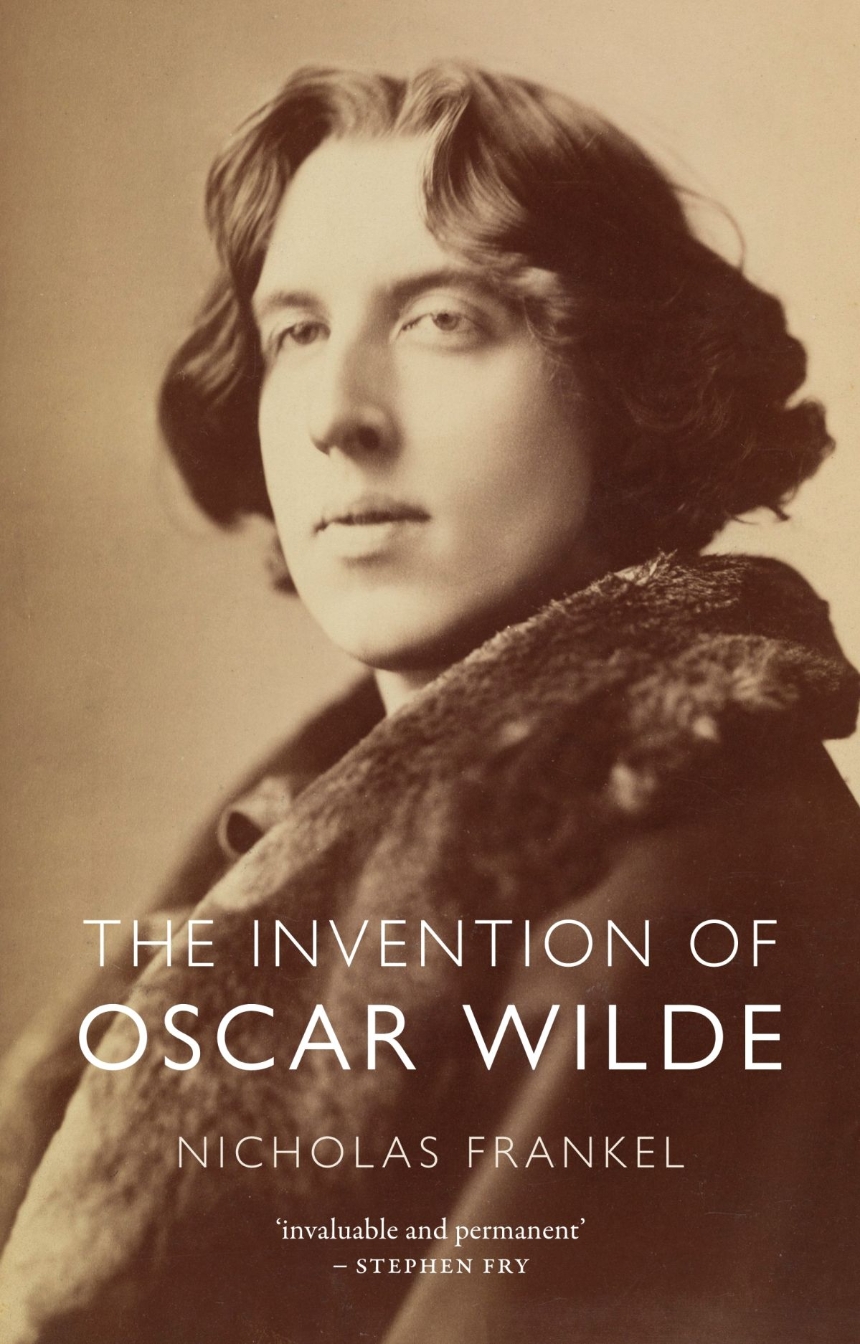

He succeeded in creating a cult of himself long before he published anything of note. Even as an undergraduate he developed that personal style and sartorial elegance for which he later became internationally famous. In 1882 the American celebrity photographer Napoleon Sarony paid $1,500, the same sum he paid to the actresses Sarah Bernhardt and Lillie Langtry, for exclusive American rights to Wilde’s photographic image, and it is not insignificant that one of the resulting photo-portraits was the subject of a landmark court case whereby photographs came to enjoy the same privileges as painted artworks in American law. Sarony’s photographs, timed to capitalize on Wilde’s 1882 tour of North America, are as ubiquitous in our own time as they were in Wilde’s day. With his long, flowing locks, cleanshaven face and love for soft, colourful clothing fabrics (‘Men should dress more in velvet . . . as it catches the light and shade,’ he said), Wilde represented a new kind of masculinity, and he had more in common with iconic male figures of the 1960s and 1970s – with Jim Morrison, Mick Jagger, David Bowie and The Beatles – than the heavily bewhiskered, moustached or bearded Victorian masculine ideal that peers out from so many Victorian portraits.

Rumours about Wilde’s unconventional sexuality accompanied these visual representations, corroborated by homoerotic strains in Wilde’s poetry and (later) his fiction. These rumours grew to a clamour in the early 1890s when his affair with the reckless Lord Alfred Douglas became the subject of gossip, culminating in his conviction and imprisonment for gross indecency in 1895. While Wilde’s sexuality cannot be made to fit easily into the modern categories of homosexual, heterosexual and bisexual, categories which are now as much markers of personal identity as of sexual taste, Wilde was unapologetic and defiant about his love for men, and today he is rightly seen as a ground-breaking figure for modern homosexual men.

But Wilde’s strong sense of personal style and elegance were not merely signs of an unconventional masculinity and sexual orientation. ‘Thou art not fit/ For this vile traffic-house,’ Wilde says to his own soul in his early poem ‘Theoretikos’, while turning contemptuously away from a world in which ‘wisdom and reverence are sold at mart’. The world of commerce and industry ‘mars my calm: wherefore, in dreams of Art/ And loftiest culture I would stand apart’. Born at the height of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Wilde early on declared a personal allegiance to art and beauty that is as clear in his surviving portraits as it is in his writings. While still a young man, he surrounded himself with fine paintings and objects, advising his listeners to transform their lived environments into small palaces of art. His earliest writings are works of art criticism, or imitations of Classical and Romantic poetry, and as W. P. Frith’s famous painting A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881 shows, Wilde himself was a compelling object of fascination no less than the artworks he criticized or endorsed with his pen.

It is often said that he was the greatest dandy of his – or any – age. But if Wilde was ‘a Man whose trade, office and existence consists in the wearing of Clothes’, to employ Thomas Carlyle’s definition of a dandy, this should not be mistaken as implying a thoughtless self-indulgence or self-absorption. In his visual and sartorial self-invention, Wilde exemplified Baudelaire’s concept of the dandy as ‘the supreme incarnation of the idea of beauty transported into the sphere of material life’. In an age of gross materialism, industry and commerce, his personal artistry and elegance stood as a rebuke to the dominant values of his age, harking back to such figures as Byron and Beau Brummell even as they insisted on what Wilde called ‘the absolute modernity of Beauty’.

We can now see that Wilde’s dandyism and love of art masked his unconventional sexuality, as his aphorism ‘to reveal art and conceal the artist is art’s aim’ may tacitly acknowledge. Forced to defend The Picture of Dorian Gray in court in 1895, he insisted that far from depicting male same-sex love, his intentions in writing the novel had been thoroughly artistic, much like those of the painter Basil Hallward, whose painting of Dorian Gray represents the ‘visible incarnation’ of an unseen, Platonic ideal. But in dramatizing Hallward’s artistic motivations in the revised book-length version of Dorian Gray published in 1891, one year after the novel’s appearance in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, Wilde simultaneously occluded motivations that were more frankly personal and sexual in earlier versions, almost certainly because scandalized reactions to the serial version raised fears of prosecution in the minds of author and publisher. ‘There was love in every line [of the portrait], and in every touch there was passion,’ Hallward confesses in the uncensored text of the novel that Wilde submitted for publication in April 1890. ‘I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend,’ he tells Dorian Gray in a phrase that Wilde’s first editor altered to the more censorious ‘more romance of feeling than a man should ever give to a friend’ (in the first published version) and that Wilde cut entirely from the book version. Hallward’s confession might easily have been made by Wilde himself, whose ‘worship’ of numerous young men is palpable in his correspondence and who later confessed that ‘Basil Hallward is who I think I am.’ It uncannily foreshadows Wilde’s own worship of Lord Alfred Douglas, the preternaturally youthful-looking young aristocrat whom Wilde once called ‘the supreme, the perfect love of my life’ and whose shadow looms over the final turbulent years of Wilde’s life.

But if Wilde gave rein to his imagination in his works, his invention and commitment to art were such that his life now reads like the greatest of his works. One should either wear a work of art or be a work of art, he declared. As we shall see, even as a young man he was determined to approach life on his own terms, and he remained an antinomian till his dying day, seizing at experience and unsettling the preconceptions of his fellow Victorians. In what he said and did – and even in the way he dressed, no less than in what he wrote – his life embodied a provocation and a rebuke to the pious conformism, cruelty and hypocrisy of Victorian England. Indeed he was never at home in England, where he spent the most successful years (1874–95) of his life and where he was always viewed as a rare exotic. Born in Ireland in 1854, he found the more open, tolerant atmosphere of France and the United States more conducive to his temper and sexuality, and he vowed to take up citizenship in France long before his final exile there following his release from an English prison in 1897.

If he was always at odds with England, however, he nevertheless lived among the English with rare passion, conviction and imagination, treating life as if it were the greatest of all arts. He was determined to put into practice Walter Pater’s injunction that ‘to burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life’. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, he called for a new spirituality of the senses; and like the eponymous hero of his own novel, Wilde’s object was nothing less than ‘to recreate life, and . . . save it from . . . harsh, uncomely puritanism’. Imprisoned for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895, he famously said that the company of male sex workers and blackmailers was like ‘feasting with panthers. The danger was half the excitement,’ and he emerged from prison under the pseudonym Sebastian Melmoth more determined than ever to follow his own path. It has been said that in his plays and stories Wilde dramatized the emergence of what the Situationist philosopher Guy Debord called a ‘society of the spectacle’, a world of conspicuous material consumption in which even language operates like a commodity or visual fetish. But Wilde’s greatest spectacle was himself: renowned in his own day for his sparkling conversation and wit no less than for his impeccable grooming and couture, he lived with self-conscious deliberateness and flamboyance – a living paradox, at once a creature of this world and apart from it. And if his written works stand in judgement on Victorian England, heralding the modern period that he helped bring into being, so too does Wilde’s uncompromising and novelistic life.

He succeeded in creating a cult of himself long before he published anything of note. Even as an undergraduate he developed that personal style and sartorial elegance for which he later became internationally famous. In 1882 the American celebrity photographer Napoleon Sarony paid $1,500, the same sum he paid to the actresses Sarah Bernhardt and Lillie Langtry, for exclusive American rights to Wilde’s photographic image, and it is not insignificant that one of the resulting photo-portraits was the subject of a landmark court case whereby photographs came to enjoy the same privileges as painted artworks in American law. Sarony’s photographs, timed to capitalize on Wilde’s 1882 tour of North America, are as ubiquitous in our own time as they were in Wilde’s day. With his long, flowing locks, cleanshaven face and love for soft, colourful clothing fabrics (‘Men should dress more in velvet . . . as it catches the light and shade,’ he said), Wilde represented a new kind of masculinity, and he had more in common with iconic male figures of the 1960s and 1970s – with Jim Morrison, Mick Jagger, David Bowie and The Beatles – than the heavily bewhiskered, moustached or bearded Victorian masculine ideal that peers out from so many Victorian portraits.

Rumours about Wilde’s unconventional sexuality accompanied these visual representations, corroborated by homoerotic strains in Wilde’s poetry and (later) his fiction. These rumours grew to a clamour in the early 1890s when his affair with the reckless Lord Alfred Douglas became the subject of gossip, culminating in his conviction and imprisonment for gross indecency in 1895. While Wilde’s sexuality cannot be made to fit easily into the modern categories of homosexual, heterosexual and bisexual, categories which are now as much markers of personal identity as of sexual taste, Wilde was unapologetic and defiant about his love for men, and today he is rightly seen as a ground-breaking figure for modern homosexual men.

But Wilde’s strong sense of personal style and elegance were not merely signs of an unconventional masculinity and sexual orientation. ‘Thou art not fit/ For this vile traffic-house,’ Wilde says to his own soul in his early poem ‘Theoretikos’, while turning contemptuously away from a world in which ‘wisdom and reverence are sold at mart’. The world of commerce and industry ‘mars my calm: wherefore, in dreams of Art/ And loftiest culture I would stand apart’. Born at the height of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Wilde early on declared a personal allegiance to art and beauty that is as clear in his surviving portraits as it is in his writings. While still a young man, he surrounded himself with fine paintings and objects, advising his listeners to transform their lived environments into small palaces of art. His earliest writings are works of art criticism, or imitations of Classical and Romantic poetry, and as W. P. Frith’s famous painting A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881 shows, Wilde himself was a compelling object of fascination no less than the artworks he criticized or endorsed with his pen.

It is often said that he was the greatest dandy of his – or any – age. But if Wilde was ‘a Man whose trade, office and existence consists in the wearing of Clothes’, to employ Thomas Carlyle’s definition of a dandy, this should not be mistaken as implying a thoughtless self-indulgence or self-absorption. In his visual and sartorial self-invention, Wilde exemplified Baudelaire’s concept of the dandy as ‘the supreme incarnation of the idea of beauty transported into the sphere of material life’. In an age of gross materialism, industry and commerce, his personal artistry and elegance stood as a rebuke to the dominant values of his age, harking back to such figures as Byron and Beau Brummell even as they insisted on what Wilde called ‘the absolute modernity of Beauty’.

We can now see that Wilde’s dandyism and love of art masked his unconventional sexuality, as his aphorism ‘to reveal art and conceal the artist is art’s aim’ may tacitly acknowledge. Forced to defend The Picture of Dorian Gray in court in 1895, he insisted that far from depicting male same-sex love, his intentions in writing the novel had been thoroughly artistic, much like those of the painter Basil Hallward, whose painting of Dorian Gray represents the ‘visible incarnation’ of an unseen, Platonic ideal. But in dramatizing Hallward’s artistic motivations in the revised book-length version of Dorian Gray published in 1891, one year after the novel’s appearance in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, Wilde simultaneously occluded motivations that were more frankly personal and sexual in earlier versions, almost certainly because scandalized reactions to the serial version raised fears of prosecution in the minds of author and publisher. ‘There was love in every line [of the portrait], and in every touch there was passion,’ Hallward confesses in the uncensored text of the novel that Wilde submitted for publication in April 1890. ‘I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend,’ he tells Dorian Gray in a phrase that Wilde’s first editor altered to the more censorious ‘more romance of feeling than a man should ever give to a friend’ (in the first published version) and that Wilde cut entirely from the book version. Hallward’s confession might easily have been made by Wilde himself, whose ‘worship’ of numerous young men is palpable in his correspondence and who later confessed that ‘Basil Hallward is who I think I am.’ It uncannily foreshadows Wilde’s own worship of Lord Alfred Douglas, the preternaturally youthful-looking young aristocrat whom Wilde once called ‘the supreme, the perfect love of my life’ and whose shadow looms over the final turbulent years of Wilde’s life.