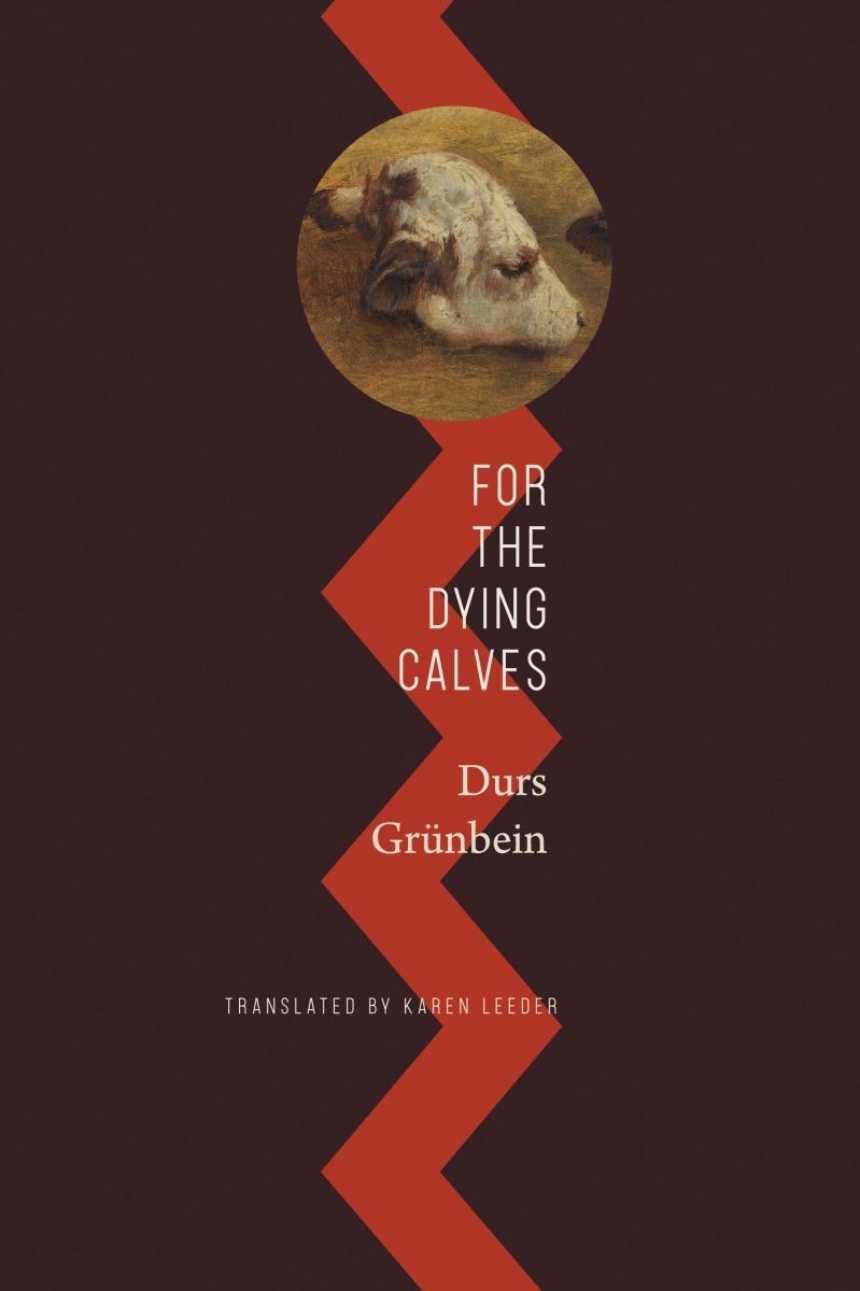

Poetically written and originally given as lectures, this is a moving essay collection from Durs Grünbein.

In his four Lord Weidenfeld Lectures held in Oxford in 2019, German poet Durs Grünbein dealt with a topic that has occupied his mind ever since he began to perceive his own position within the past of his nation, his linguistic community, and his family: How is it possible that history can determine the individual poetic imagination and segregate it into private niches? Shouldn’t poetry look at the world with its own sovereign eyes instead?

In the form of a collage or “photosynthesis,” in image and text, Grünbein lets the fundamental opposition between poetic license and almost overwhelming bondage to history appear in an exemplary way. From the seeming trifle of a stamp with the portrait of Adolf Hitler, he moves through the phenomenon of the “Führer’s streets” and into the inferno of aerial warfare. In the end, Grünbein argues that we are faced with the powerlessness of writing and the realization, valid to this day, that comes from confronting history. As he muses, “There is something beyond literature that questions all writing.”

In his four Lord Weidenfeld Lectures held in Oxford in 2019, German poet Durs Grünbein dealt with a topic that has occupied his mind ever since he began to perceive his own position within the past of his nation, his linguistic community, and his family: How is it possible that history can determine the individual poetic imagination and segregate it into private niches? Shouldn’t poetry look at the world with its own sovereign eyes instead?

In the form of a collage or “photosynthesis,” in image and text, Grünbein lets the fundamental opposition between poetic license and almost overwhelming bondage to history appear in an exemplary way. From the seeming trifle of a stamp with the portrait of Adolf Hitler, he moves through the phenomenon of the “Führer’s streets” and into the inferno of aerial warfare. In the end, Grünbein argues that we are faced with the powerlessness of writing and the realization, valid to this day, that comes from confronting history. As he muses, “There is something beyond literature that questions all writing.”

Reviews

Table of Contents

Excerpt

I had given up stamp-collecting at some point; the albums vanished into the attic like so much else. Years later, as I was leafing through them, a battlefield postcard fluttered into my hands with a violet postage stamp. It was its provocative hue, the purple of wolfsbane, that set my thoughts racing in strange directions. The same print of the Führer’s head existed in pea green, chestnut-brown, blood-red, it even popped up in the harmless orange color of southern fruit. Letters and post cards bearing the threatening likeness had been sent out into all corners of the world. Loaded onto express trains they crisscrossed the awakening Fatherland and were dis-patched by air mail as far as America, China and Australia. When I think back now to all those uniforms little stamps the mass character of National Socialism becomes immediately apparent. I ask myself how many million people must have licked Hitler at that time, willingly or unwillingly, but licked him, nonetheless. This vision of multi tongued slavishness, silver-tongued duplicity, sticky servility has something repulsive about it.

If it wasn’t the sponge on the post office counter, then a human tongue must have moistened the reverse. I imagine all the times that happened, all those unnoticed, intimate moments, the occasions involved and the different sites within the new European theatre of war. The bright July day at a table in a Munich beer garden, or late summer in Vienna sitting beneath the vine tendrils, drinking the early wine and sending greetings to loved ones at home. A postcard to an aunt, sealed with at hump of the fist on the obstinate stamp when the soldier’s mate had disappeared to the toilet. Or sticking one on to the billet doux intended for the beloved, in high spirits, months before the order to leave for the front. A winter evening in the guard room of a barracks in Occupied Poland, forces mail after leave in Warsaw, walking alongside the fences of the newly erected ghetto; one soldier writing to his mother: ‘it’s still crawling with Jews here. ’Or sent from a barracks in Occupied Lublin on the anniversary of ‘Two Years of General Government’ in Poland. From a Berlin dive after a sleepless night, hours before boarding the troop trains to Russia.

Each time it was the same unconscious act, something an ape might do—like picking over a coat for lice, licking a stick covered with ants—a conditioned reflex; one of many necessities in our modern life. People who caught themselves doing it were likely ashamed for a split second, then came a passing anxiety about catching something, but the next moment it was forgotten, and they had already moistened the next stamp.

If it wasn’t the sponge on the post office counter, then a human tongue must have moistened the reverse. I imagine all the times that happened, all those unnoticed, intimate moments, the occasions involved and the different sites within the new European theatre of war. The bright July day at a table in a Munich beer garden, or late summer in Vienna sitting beneath the vine tendrils, drinking the early wine and sending greetings to loved ones at home. A postcard to an aunt, sealed with at hump of the fist on the obstinate stamp when the soldier’s mate had disappeared to the toilet. Or sticking one on to the billet doux intended for the beloved, in high spirits, months before the order to leave for the front. A winter evening in the guard room of a barracks in Occupied Poland, forces mail after leave in Warsaw, walking alongside the fences of the newly erected ghetto; one soldier writing to his mother: ‘it’s still crawling with Jews here. ’Or sent from a barracks in Occupied Lublin on the anniversary of ‘Two Years of General Government’ in Poland. From a Berlin dive after a sleepless night, hours before boarding the troop trains to Russia.

Each time it was the same unconscious act, something an ape might do—like picking over a coat for lice, licking a stick covered with ants—a conditioned reflex; one of many necessities in our modern life. People who caught themselves doing it were likely ashamed for a split second, then came a passing anxiety about catching something, but the next moment it was forgotten, and they had already moistened the next stamp.