9781789144444

9781789144451

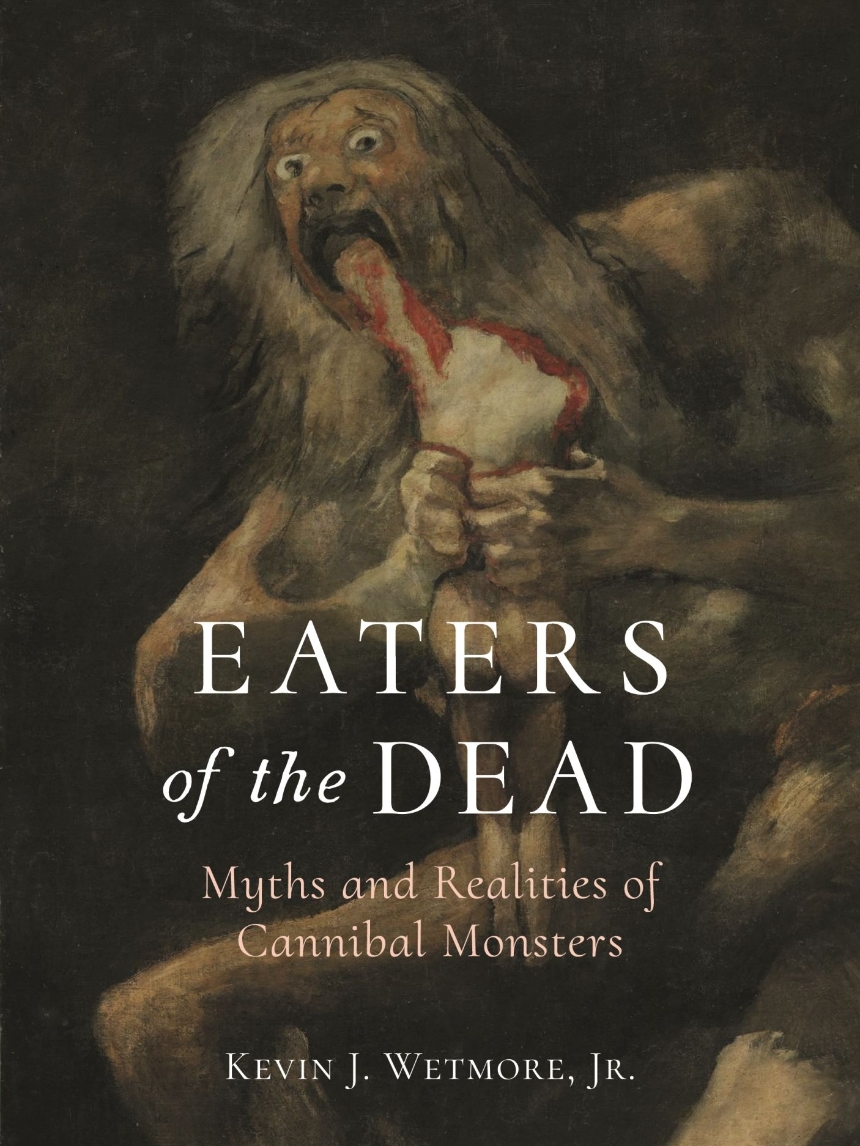

Spanning myth, history, and contemporary culture, a terrifying and illuminating excavation of the meaning of cannibalism.

Every culture has monsters that eat us, and every culture repels in horror when we eat ourselves. From Grendel to medieval Scottish cannibal Sawney Bean, and from the Ghuls of ancient Persia to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, tales of being consumed are both universal and universally terrifying. In this book, Kevin J. Wetmore Jr. explores the full range of monsters that eat the dead: ghouls, cannibals, wendigos, and other beings that feast on human flesh. Moving from myth through history to contemporary popular culture, Wetmore considers everything from ancient Greek myths of feeding humans to the gods, through sky burial in Tibet and Zoroastrianism, to actual cases of cannibalism in modern societies. By examining these seemingly inhuman acts, Eaters of the Dead reveals that those who consume corpses can teach us a great deal about human nature—and our deepest human fears.

Every culture has monsters that eat us, and every culture repels in horror when we eat ourselves. From Grendel to medieval Scottish cannibal Sawney Bean, and from the Ghuls of ancient Persia to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, tales of being consumed are both universal and universally terrifying. In this book, Kevin J. Wetmore Jr. explores the full range of monsters that eat the dead: ghouls, cannibals, wendigos, and other beings that feast on human flesh. Moving from myth through history to contemporary popular culture, Wetmore considers everything from ancient Greek myths of feeding humans to the gods, through sky burial in Tibet and Zoroastrianism, to actual cases of cannibalism in modern societies. By examining these seemingly inhuman acts, Eaters of the Dead reveals that those who consume corpses can teach us a great deal about human nature—and our deepest human fears.

Reviews

Excerpt

The dead are consumed by insects and bacteria, by flame, by animals and, in some cases, by people. Even the word ‘sarcophagus’, which describes a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, literally means ‘flesh-eater’ (sarx plus phagos). When we place someone in a sarcophagus, the implication is that the casket itself is eating the dead body. The end result of death is to be eaten by, well, something.

By extension, we have a history of imagining and creating beasts that eat the dead. People who witness corpses being scavenged by dogs, vultures, hyenas and other animals can imagine monstrous beings that do the same. Through recorded human history we hear tales of survival cannibalism: sometimes during periods of famine or food scarcity the only available food is the people who died of starvation before you. Whether sailors stranded in a lifeboat for months, populations undergoing famine during war or winter, or people trapped in the mountains awaiting rescue, history is full of tales of people forced to eat the dead to survive. From the Donner Party to the ‘Great Hunger’ of Ireland, to the plane crash that stranded the Uruguayan rugby team in the Andes in 1972, we know the names of those who had to eat and those who were eaten. We also know tales of criminal cannibals – those who choose to eat the dead for a number of reasons. There is a reason the world knows of Jeffrey Dahmer and that Ed Gein inspired not one, not two, but half a dozen films, including The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Silence of the Lambs and Psycho, not to mention the lesser-known Ed Gein and Ed Gein: The Butcher of Plainfield. We are drawn to tales of depraved cannibals.

Death, both our own and that of others, causes anxiety and fear. Death is not the end, however. How the body is regarded and treated (especially symbolically and mythically within that culture) reveals how a society understands death and the body. Is my body myself? How should my body be disposed of after my death? What should I fear happening to my corpse after my death? Why are Westerners, as a culture, appalled by the idea of their bodies being eaten?

The reason is the universal fear of being eaten. Indeed, some psychologists believe that our fear of the dark is less to do with the unknown and more to do with our memory of being prey. The things that lurk in the dark are what scare us, primarily because we might be eaten. While being bitten by a venomous snake is horrible, we react so much more strongly to someone being bitten (and perhaps partly devoured) by a shark. In both cases an animal’s bite causes an injury, but the idea of our bodies being consumed strikes us as so much worse. As Val Plumwood, who survived being bitten and chewed by a crocodile, observes, ‘If ordinary death is a horror, death in the jaws of a crocodile is the ultimate horror.’ I think there is a source to be found in that experience for many man-eating myths, not to mention the more recent anthropological theory that our species survived because we ate the Neanderthals. They were our closest genetic relatives and we considered them a food source.

Devouring, consuming and eating are all metaphors. But they are also real fears and the source of genuine horror. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen reminds us that we can ‘read cultures from the monsters they engender’. This book is a buffet of corpse-eaters from all over the world, each one telling us about the cultures that created them. We shall examine how stories, myths and histories explore these fears, taboos and metaphors. We shall consider what monsters emerge from them, how popular culture, particularly in the West, has used those monsters to create new and scary stories, and what they all mean. Let’s dig in. Bon appétit!

By extension, we have a history of imagining and creating beasts that eat the dead. People who witness corpses being scavenged by dogs, vultures, hyenas and other animals can imagine monstrous beings that do the same. Through recorded human history we hear tales of survival cannibalism: sometimes during periods of famine or food scarcity the only available food is the people who died of starvation before you. Whether sailors stranded in a lifeboat for months, populations undergoing famine during war or winter, or people trapped in the mountains awaiting rescue, history is full of tales of people forced to eat the dead to survive. From the Donner Party to the ‘Great Hunger’ of Ireland, to the plane crash that stranded the Uruguayan rugby team in the Andes in 1972, we know the names of those who had to eat and those who were eaten. We also know tales of criminal cannibals – those who choose to eat the dead for a number of reasons. There is a reason the world knows of Jeffrey Dahmer and that Ed Gein inspired not one, not two, but half a dozen films, including The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Silence of the Lambs and Psycho, not to mention the lesser-known Ed Gein and Ed Gein: The Butcher of Plainfield. We are drawn to tales of depraved cannibals.

Death, both our own and that of others, causes anxiety and fear. Death is not the end, however. How the body is regarded and treated (especially symbolically and mythically within that culture) reveals how a society understands death and the body. Is my body myself? How should my body be disposed of after my death? What should I fear happening to my corpse after my death? Why are Westerners, as a culture, appalled by the idea of their bodies being eaten?

The reason is the universal fear of being eaten. Indeed, some psychologists believe that our fear of the dark is less to do with the unknown and more to do with our memory of being prey. The things that lurk in the dark are what scare us, primarily because we might be eaten. While being bitten by a venomous snake is horrible, we react so much more strongly to someone being bitten (and perhaps partly devoured) by a shark. In both cases an animal’s bite causes an injury, but the idea of our bodies being consumed strikes us as so much worse. As Val Plumwood, who survived being bitten and chewed by a crocodile, observes, ‘If ordinary death is a horror, death in the jaws of a crocodile is the ultimate horror.’ I think there is a source to be found in that experience for many man-eating myths, not to mention the more recent anthropological theory that our species survived because we ate the Neanderthals. They were our closest genetic relatives and we considered them a food source.

Devouring, consuming and eating are all metaphors. But they are also real fears and the source of genuine horror. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen reminds us that we can ‘read cultures from the monsters they engender’. This book is a buffet of corpse-eaters from all over the world, each one telling us about the cultures that created them. We shall examine how stories, myths and histories explore these fears, taboos and metaphors. We shall consider what monsters emerge from them, how popular culture, particularly in the West, has used those monsters to create new and scary stories, and what they all mean. Let’s dig in. Bon appétit!