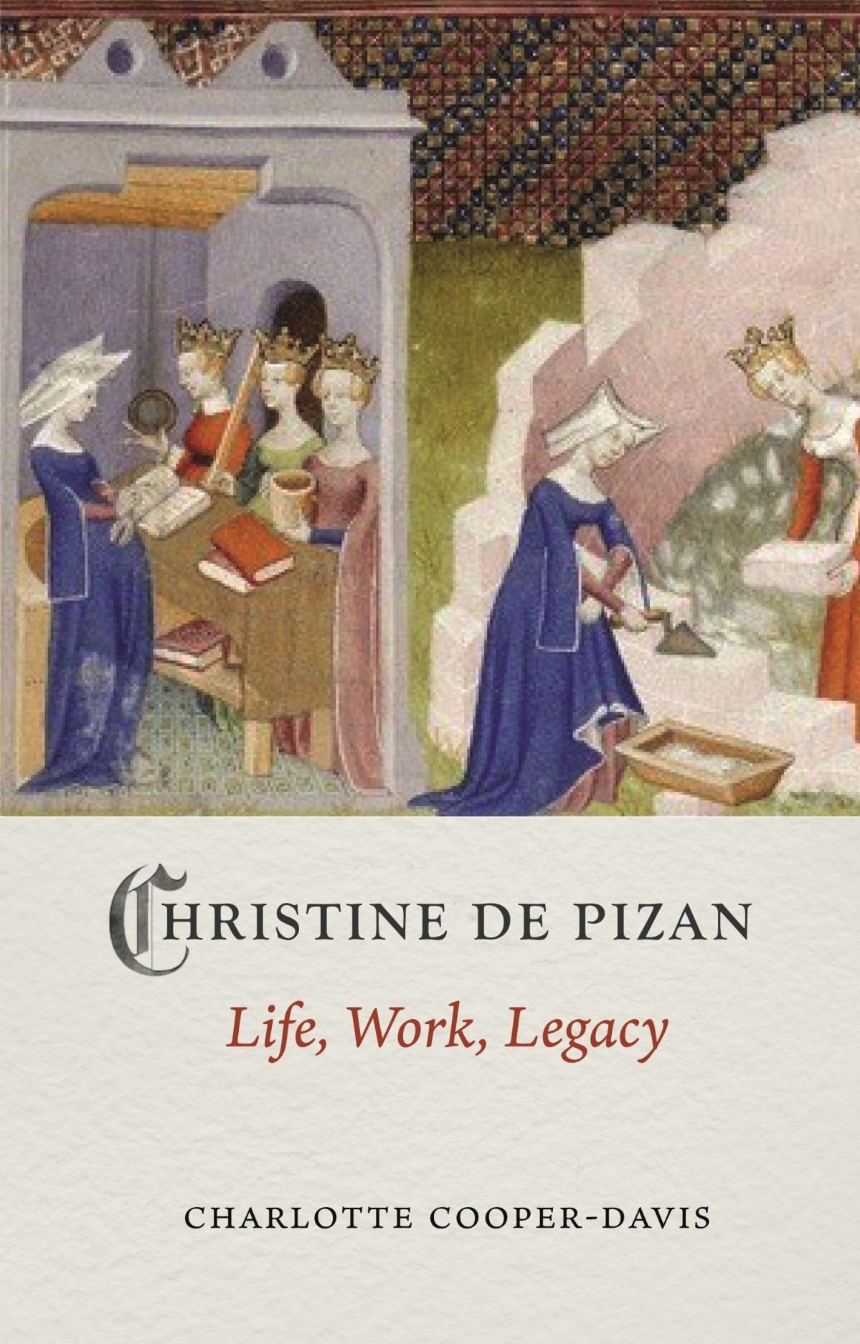

The first popular biography of a pioneering feminist thinker and writer of medieval Paris.

The daughter of a court intellectual, Christine de Pizan dwelled within the cultural heart of late-medieval Paris. In the face of personal tragedy, she learned the tools of the book trade, writing more than forty works that included poetry, historical and political treatises, and defenses of women. In this new biography—the first written for a general audience—Charlotte Cooper-Davis discusses the life and work of this pioneering female thinker and writer. She shows how Christine de Pizan’s inspiration came from the world around her, situates her as an entrepreneur within the context of her times and place, and finally examines her influence on the most avant-garde of feminist artists, through whom she is slowly making a return into mainstream popular culture.

The daughter of a court intellectual, Christine de Pizan dwelled within the cultural heart of late-medieval Paris. In the face of personal tragedy, she learned the tools of the book trade, writing more than forty works that included poetry, historical and political treatises, and defenses of women. In this new biography—the first written for a general audience—Charlotte Cooper-Davis discusses the life and work of this pioneering female thinker and writer. She shows how Christine de Pizan’s inspiration came from the world around her, situates her as an entrepreneur within the context of her times and place, and finally examines her influence on the most avant-garde of feminist artists, through whom she is slowly making a return into mainstream popular culture.

224 pages | 12 color plates, 14 halftones | 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 | © 2021

Reviews

Excerpt

Few medieval writers were as prolific as Christine de Pizan. Over a career that spanned almost four decades, she composed around thirty major works as well as several shorter poems. These survive in over two hundred manuscripts – an extraordinary figure for an individual medieval author. For comparison, just a single manuscript exists of the Old English epic poem Beowulf and even Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, which were being composed around the time that Christine was writing, survive in only 32 copies. What is even more remarkable in Christine’s case is that she oversaw the production of 54 of her manuscripts herself and several of them are written in her own hand. It is not known how many further copies of her works are likely to have been lost over the centuries.

Such an enormous literary production would not have been possible had its executor not been deeply familiar with contemporary culture and compositional practices. For her works to circulate, a pragmatic knowledge of writing, bookmaking and booktrading was required; for them to be popular, they needed to display a mastery of popular and fashionable poetic themes, which would also secure her valuable patronage from some of the highest-ranking nobles of the time. Gaining the dexterity required to be proficient in these various areas was no easy task in the Middle Ages – especially for a woman without a clerical education – so despite her prolific output, Christine did not turn to writing until relatively late in life. Before she was to take up her pen, her life was to undergo a series of twists and turns that would set her on the path to becoming an author.

Christine was born in Venice around 1364, but she only spent a short amount of time in that city. Her father, Thomas de Pizan – Thomasso de Benvenuto da Pizzano, to give him his full Italian name – was appointed astrologer to the French court in Paris shortly before 1368. Once he had settled in the city, he sent for his family to join him. It was through her father and his position that Christine first became embedded in the literary and scholastic culture of the late European Middle Ages. When she was born, Thomas was a lecturer at the prestigious Italian University of Bologna, which he had also attended as a student and where he was a contemporary of the poet and scholar Petrarch. The education that he received would have been second to none. He trained to become a doctor in medical studies, which required studying the arts along with astrology and natural philosophy, mathematics, logic and rhetoric. In her writings, Christine remembers her father with great fondness as someone who was ‘famous everywhere as a celebrated scholar’, from whom she humbly claims to have gathered only ‘the crumbs falling from the high table . . . when fine dishes are served up’. She describes how Thomas encouraged her in her own learning and did not see her sex as an obstacle to erudition. As one of the characters in Le Livre de la cité des dames (The Book of the City of Ladies) reminds her: ‘he was delighted to see your passion for study.’

A love of learning ran in the family. This was probably what drew Thomas to accept the position at the French court, which was famous for its intellectual culture (he turned down a similar role he had been offered at the court of Hungary when forced to choose between the two). King Charles v of France, who came to the throne around the same time that Christine was born, was a monarch committed to learning. He had recently embarked upon a huge enterprise, known as his Sapientia (meaning ‘knowledge’) project, which involved investing heavily in new books that would be housed in a sumptuous new library in the Louvre. To do so, he commissioned numerous writers and artisans to fill his shelves with new works – these were not only literary works, but testaments to the various forms of cultural and artistic practices that were thriving in Paris at the time. Charles V’s project did not just require authors and scribes to compose and copy the texts, but the work of translators, illuminators and artists, bookmakers, carpenters and metalworkers, architects and designers. Meanwhile, the flourishing University of Paris (of which Charles was a patron) continued to attract leading scholars to the city, many of whom went on to take up positions at the royal court. Through her father’s work, Christine would get to know many of the people who carried out these duties in a personal capacity.

This thriving intellectual and artistic atmosphere formed the backdrop to Christine’s youth. Without the benefit of such a rich cultural background or her father’s connections, she might not have had access to the materials that enabled her career as a writer to take shape. Yet, although she undoubtedly enjoyed a period of great happiness, the circumstances that led her to take on this role are hardly enviable.

At Fortune's Mercy

When she was fifteen years old, Christine married a royal secretary named Etienne de Castel, who was about ten years her senior. Like her father, Etienne was university-educated, and Christine describes her admiration for his great learning in similar terms to those she expresses for her father. Although her husband was chosen by Thomas, there is no reason to believe the union was anything but happy. Christine herself concedes that ‘truly . . . I would not have essayed to choose better by my own wishes.’ She often refers to her eleven-year marriage in her writings, where her husband is mentioned only with fondness. In the autobiographical passages of Le Livre de la mutacion de Fortune (The Book of Fortune’s Transformation) he is described as ‘a handsome, pleasing youth’ whose company she enjoyed and who ‘was so faithful to me, and so good that . . . I could not praise highly enough the good things that I received from him.’ She and Etienne had three children together, two of whom survived. One of them, Jean de Castel, also went on to have a career as a writer. The decade of Christine’s life during which she was married was a happy and prosperous time for her and her family.

Alas, it was not to last. Between 1380 and 1390 Christine was dealt a series of blows, starting with the death of Charles v, who – as employer to both her husband and father – was her family’s main protector. Etienne and Thomas’s financial situations both suffered as a result. In Le Livre de l’avision Cristine (The Book of Christine’s Vision), the third part of which is largely autobiographical, she describes the effects of the king’s death on her father’s income, including his loss of pensions and other benefits. It is unclear how long Thomas outlived his protector, but he is believed to have died sometime in the late 1380s. Christine has recourse to a common metaphor to relate the tragedies that afflicted her at this time – that of the wheel of Fortune. Up until now, she says, Fortune had smiled on her, provided for her and looked after her, but now she had ‘placed me in the downward swing of her wheel, set towards the misfortunes she wished to give me to throw me as low as possible’. The final turn of Fortune’s wheel came in 1390. Etienne was with the new king on a mission in Beauvais when an epidemic struck. He did not survive the outbreak. Etienne’s death left Christine widowed in her mid-twenties,with three children, a mother and a niece to feed.

Christine’s life was transformed as she was left to fend for her young family. But although her finances suffered immensely with the deaths of the family’s two main earners, her position could have been much worse. At the height of his power, Thomas had earned a very good income – estimated at around 1,920 livres parisis (the main currency in which accounts were paid in Paris at that time) per annum. At the time, the income of even the middle nobility was only around a quarter of that amount. Although the family’s finances suffered enormously, their background was sufficiently wealthy for the effects of these events not to be entirely devastating. Christine and her two brothers, who by now were back in Italy, inherited property from their father both in France and in their native land. Thomas’s property in Melun was later sold by Christine to an old friend of the family’s, the author Philippe de Mézières – himself a minor noble and just one of the family’s many important connections. As for Etienne’s estate, for fourteen years Christine fought various lawsuits that would release her from responsibility for her husband’s property. The details of these lawsuits are unknown but it is probably the case that Christine was being forced to pay rent on Etienne’s property even though it had reverted to the crown upon his death. Meanwhile, the debtors who owed money to the estate avoided and eluded her. Christine speaks candidly of her economic difficulties in the Avision, but it is important to remember that she was never so desperate as to be forced to work or to remarry – as was so often the case for upper-class widows in the Middle Ages. She did need to support her family, however, and to justify and ensure their continued presence at court by maintaining the powerful connections that her husband and father had fostered. And so, she turned to writing.

Such an enormous literary production would not have been possible had its executor not been deeply familiar with contemporary culture and compositional practices. For her works to circulate, a pragmatic knowledge of writing, bookmaking and booktrading was required; for them to be popular, they needed to display a mastery of popular and fashionable poetic themes, which would also secure her valuable patronage from some of the highest-ranking nobles of the time. Gaining the dexterity required to be proficient in these various areas was no easy task in the Middle Ages – especially for a woman without a clerical education – so despite her prolific output, Christine did not turn to writing until relatively late in life. Before she was to take up her pen, her life was to undergo a series of twists and turns that would set her on the path to becoming an author.

Christine was born in Venice around 1364, but she only spent a short amount of time in that city. Her father, Thomas de Pizan – Thomasso de Benvenuto da Pizzano, to give him his full Italian name – was appointed astrologer to the French court in Paris shortly before 1368. Once he had settled in the city, he sent for his family to join him. It was through her father and his position that Christine first became embedded in the literary and scholastic culture of the late European Middle Ages. When she was born, Thomas was a lecturer at the prestigious Italian University of Bologna, which he had also attended as a student and where he was a contemporary of the poet and scholar Petrarch. The education that he received would have been second to none. He trained to become a doctor in medical studies, which required studying the arts along with astrology and natural philosophy, mathematics, logic and rhetoric. In her writings, Christine remembers her father with great fondness as someone who was ‘famous everywhere as a celebrated scholar’, from whom she humbly claims to have gathered only ‘the crumbs falling from the high table . . . when fine dishes are served up’. She describes how Thomas encouraged her in her own learning and did not see her sex as an obstacle to erudition. As one of the characters in Le Livre de la cité des dames (The Book of the City of Ladies) reminds her: ‘he was delighted to see your passion for study.’

A love of learning ran in the family. This was probably what drew Thomas to accept the position at the French court, which was famous for its intellectual culture (he turned down a similar role he had been offered at the court of Hungary when forced to choose between the two). King Charles v of France, who came to the throne around the same time that Christine was born, was a monarch committed to learning. He had recently embarked upon a huge enterprise, known as his Sapientia (meaning ‘knowledge’) project, which involved investing heavily in new books that would be housed in a sumptuous new library in the Louvre. To do so, he commissioned numerous writers and artisans to fill his shelves with new works – these were not only literary works, but testaments to the various forms of cultural and artistic practices that were thriving in Paris at the time. Charles V’s project did not just require authors and scribes to compose and copy the texts, but the work of translators, illuminators and artists, bookmakers, carpenters and metalworkers, architects and designers. Meanwhile, the flourishing University of Paris (of which Charles was a patron) continued to attract leading scholars to the city, many of whom went on to take up positions at the royal court. Through her father’s work, Christine would get to know many of the people who carried out these duties in a personal capacity.

This thriving intellectual and artistic atmosphere formed the backdrop to Christine’s youth. Without the benefit of such a rich cultural background or her father’s connections, she might not have had access to the materials that enabled her career as a writer to take shape. Yet, although she undoubtedly enjoyed a period of great happiness, the circumstances that led her to take on this role are hardly enviable.

At Fortune's Mercy

When she was fifteen years old, Christine married a royal secretary named Etienne de Castel, who was about ten years her senior. Like her father, Etienne was university-educated, and Christine describes her admiration for his great learning in similar terms to those she expresses for her father. Although her husband was chosen by Thomas, there is no reason to believe the union was anything but happy. Christine herself concedes that ‘truly . . . I would not have essayed to choose better by my own wishes.’ She often refers to her eleven-year marriage in her writings, where her husband is mentioned only with fondness. In the autobiographical passages of Le Livre de la mutacion de Fortune (The Book of Fortune’s Transformation) he is described as ‘a handsome, pleasing youth’ whose company she enjoyed and who ‘was so faithful to me, and so good that . . . I could not praise highly enough the good things that I received from him.’ She and Etienne had three children together, two of whom survived. One of them, Jean de Castel, also went on to have a career as a writer. The decade of Christine’s life during which she was married was a happy and prosperous time for her and her family.

Alas, it was not to last. Between 1380 and 1390 Christine was dealt a series of blows, starting with the death of Charles v, who – as employer to both her husband and father – was her family’s main protector. Etienne and Thomas’s financial situations both suffered as a result. In Le Livre de l’avision Cristine (The Book of Christine’s Vision), the third part of which is largely autobiographical, she describes the effects of the king’s death on her father’s income, including his loss of pensions and other benefits. It is unclear how long Thomas outlived his protector, but he is believed to have died sometime in the late 1380s. Christine has recourse to a common metaphor to relate the tragedies that afflicted her at this time – that of the wheel of Fortune. Up until now, she says, Fortune had smiled on her, provided for her and looked after her, but now she had ‘placed me in the downward swing of her wheel, set towards the misfortunes she wished to give me to throw me as low as possible’. The final turn of Fortune’s wheel came in 1390. Etienne was with the new king on a mission in Beauvais when an epidemic struck. He did not survive the outbreak. Etienne’s death left Christine widowed in her mid-twenties,with three children, a mother and a niece to feed.

Christine’s life was transformed as she was left to fend for her young family. But although her finances suffered immensely with the deaths of the family’s two main earners, her position could have been much worse. At the height of his power, Thomas had earned a very good income – estimated at around 1,920 livres parisis (the main currency in which accounts were paid in Paris at that time) per annum. At the time, the income of even the middle nobility was only around a quarter of that amount. Although the family’s finances suffered enormously, their background was sufficiently wealthy for the effects of these events not to be entirely devastating. Christine and her two brothers, who by now were back in Italy, inherited property from their father both in France and in their native land. Thomas’s property in Melun was later sold by Christine to an old friend of the family’s, the author Philippe de Mézières – himself a minor noble and just one of the family’s many important connections. As for Etienne’s estate, for fourteen years Christine fought various lawsuits that would release her from responsibility for her husband’s property. The details of these lawsuits are unknown but it is probably the case that Christine was being forced to pay rent on Etienne’s property even though it had reverted to the crown upon his death. Meanwhile, the debtors who owed money to the estate avoided and eluded her. Christine speaks candidly of her economic difficulties in the Avision, but it is important to remember that she was never so desperate as to be forced to work or to remarry – as was so often the case for upper-class widows in the Middle Ages. She did need to support her family, however, and to justify and ensure their continued presence at court by maintaining the powerful connections that her husband and father had fostered. And so, she turned to writing.