9781913368647

9781913368227

9781913368234

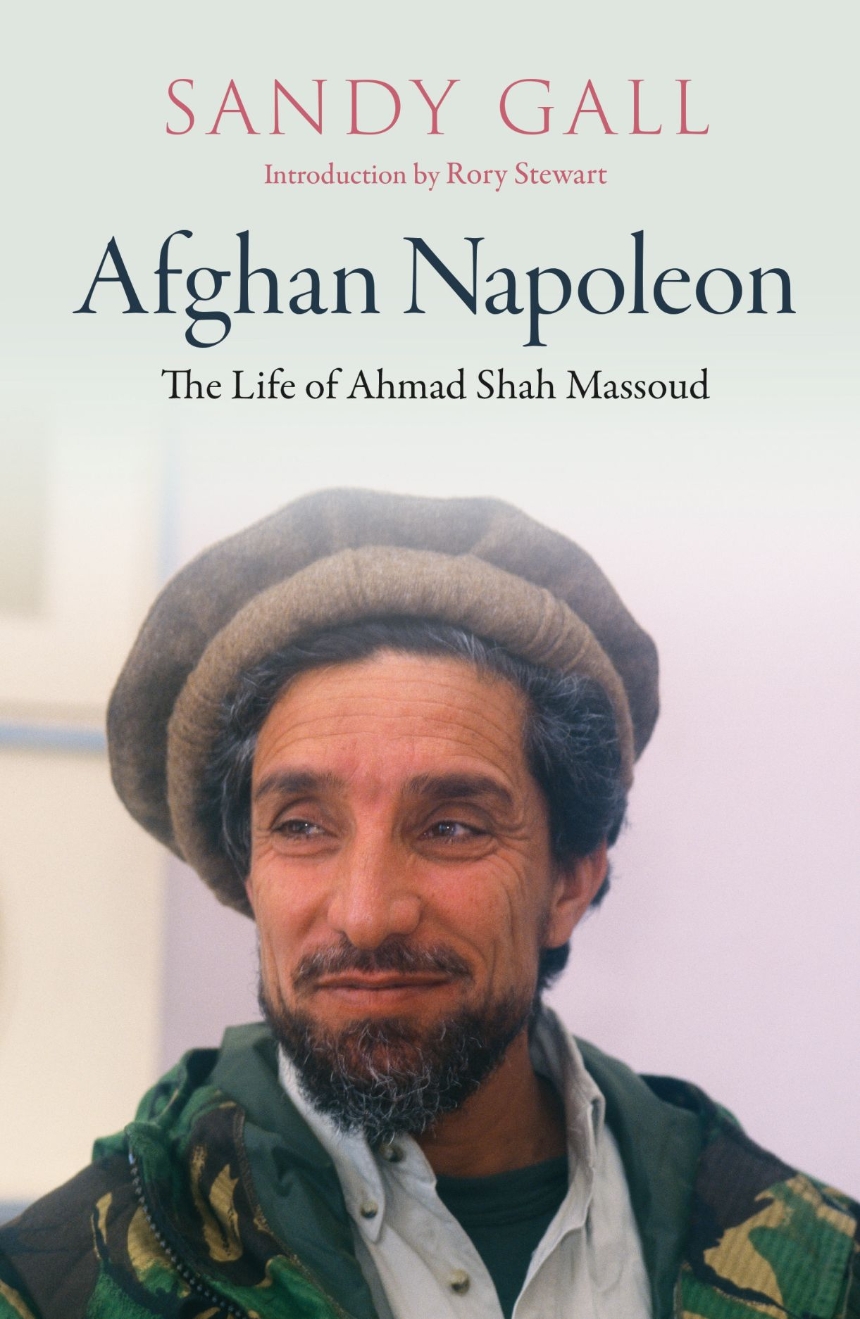

The first biography in a decade of Afghan resistance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud.

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the forces of resistance were disparate. Many groups were caught up in fighting each other and competing for Western arms. The exception were those commanded by Ahmad Shah Massoud, the military strategist and political operator who solidified the resistance and undermined the Russian occupation, leading resistance members to a series of defensive victories.

Sandy Gall followed Massoud during Soviet incursions and reported on the war in Afghanistan, and he draws on this first-hand experience in his biography of this charismatic guerrilla commander. Afghan Napoleon includes excerpts from the surviving volumes of Massoud’s prolific diaries—many translated into English for the first time—which detail crucial moments in his personal life and during his time in the resistance. Born into a liberalizing Afghanistan in the 1960s, Massoud ardently opposed communism, and he rose to prominence by coordinating the defense of the Panjsher Valley against Soviet offensives. Despite being under-equipped and outnumbered, he orchestrated a series of victories over the Russians. Massoud’s assassination in 2001, just two days before the attack on the Twin Towers, is believed to have been ordered by Osama bin Laden. Despite the ultimate frustration of Massoud’s attempts to build political consensus, he is recognized today as a national hero.

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the forces of resistance were disparate. Many groups were caught up in fighting each other and competing for Western arms. The exception were those commanded by Ahmad Shah Massoud, the military strategist and political operator who solidified the resistance and undermined the Russian occupation, leading resistance members to a series of defensive victories.

Sandy Gall followed Massoud during Soviet incursions and reported on the war in Afghanistan, and he draws on this first-hand experience in his biography of this charismatic guerrilla commander. Afghan Napoleon includes excerpts from the surviving volumes of Massoud’s prolific diaries—many translated into English for the first time—which detail crucial moments in his personal life and during his time in the resistance. Born into a liberalizing Afghanistan in the 1960s, Massoud ardently opposed communism, and he rose to prominence by coordinating the defense of the Panjsher Valley against Soviet offensives. Despite being under-equipped and outnumbered, he orchestrated a series of victories over the Russians. Massoud’s assassination in 2001, just two days before the attack on the Twin Towers, is believed to have been ordered by Osama bin Laden. Despite the ultimate frustration of Massoud’s attempts to build political consensus, he is recognized today as a national hero.

Reviews

Excerpt

Half an hour later, he had recovered his usual unflappable demeanour. Turning in his seat, he pointed out of the window. ‘This is Maiwand,’ he said, ‘where, as you know, the British suffered one of their greatest defeats in Afghanistan.’ His voice betrayed a certain relish, I thought, as the green fields of the old battlefield rolled past our windows. It was here that Malalai, the Afghan Joan of Arc, waved her veil as a standard and, as legend has it, shrieked her landay. Faisan recited, ‘Young love, if you do not fall in the battle of Maiwand, / By God, someone is saving you as a token of shame.’ He gave a little smile, as if to say he was happy not to have to report another defeat, this time at Sangin.

In the late 2010s, Sangin acquired the reputation among British troops of being the most dangerous town in Afghanistan. From the moment 3 PARA (the British army’s 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment) arrived in Sangin, its soldiers found themselves fighting for their lives to hold the district centre against successive waves of Taliban fighters determined to drive them out. In those four years, the British lost more than 100 men in Sangin, with many more wounded. But the Taliban never took the district centre.

At first, Massoud and Rabbani had welcomed the rise of the Taliban, approving of their promise to introduce law and order and rid the country of lawless banditry. Massoud and Rabbani even supplied support to the Taliban in the early days, and some Jamiat commanders had joined the movement. But Massoud changed his mind after a personal encounter with the Taliban.

In February 1995, with minimal protection, Massoud drove down to Maidanshahr, south-west of Kabul, to meet some of the Taliban leaders. The meeting came out of the Rabbani government’s early favourable contacts with the Taliban and was arranged by several Pashtun religious elders whose party, Harakat-i-Inqilab-i-Islami, was a prominent force in the Taliban. The elders also offered to mediate. Massoud agreed and asked Shamsurahman, a northern Pashtun Jamiat commander who was the military logistics chief for the Shura-i-Nazar, to join the delegation. The elders travelled to Maidanshahr to meet the Taliban and found most of the top leaders there: the deputy head of the movement, Mullah Rabbani, and the prominent military commanders Mullah Borjan, Mullah Khairkhwah, Mullah Ghous, and Abdul Wahid Baghrani – everyone but the supreme leader, Mullah Omar. Massoud’s envoys told them that Massoud wanted peace, to avert further fighting. Mullah Rabbani demanded to meet Massoud in person. When the delegation briefed Massoud the next day, one of his commanders, Registani, advised him not to go to an area under Taliban control, but Massoud was still keen, and replied that for the sake of peace he would ‘even go to Kandahar’.

The next morning, Massoud sent his senior officer, Ahmad Muslem Hayat, ahead with the elders to scope out the meeting place. Muslem found the Taliban uncooperative. On his return, Muslem met Massoud at the front line and warned him that it was a trap. He even evoked a historical precedent: the fate of the short-lived Tajik leader Habibullah Kalakani, better known as Bacha Saqao, ‘the Water Carrier’, who ruled Kabul for less than a year in 1929 and, as the story goes, was captured when invited to a meeting by his Pashtun opponents, and then executed.

‘I tried to convince [Massoud] not to go to this meeting,’ Muslem later wrote in a personal account of the meeting, ‘but my colleagues convinced him to go, as they claimed [the Taliban] were good people. He stayed quiet and did not tell us of his decision.’ Muslem recalled that Massoud then suggested they take a walk together.

As everyone waited and sat on the road, Massoud and I walked to a distant spot, and I did not know what he was going to say to me. As we walked, he stuck close to me, so the people behind could not see what we did. He asked me if I was armed and asked for my pistol. I was surprised at this question and told him that I had a Makarov and it was loaded with eight bullets, and he asked for an extra magazine. I gave him the pistol and told him I didn’t have an extra magazine, and then he turned to walk back toward the others. At this point, I was upset and started to question his actions and told him not to go forward with this meeting, because of past events with King Habibullah, who was killed in a similar fashion. I told him, ‘This is your last chance, because they will capture you and execute you.’ I kept trying to convince him, but he told me that he had made his decision and he had to go. I got a severe headache …it felt like my head was going to explode. He told me to stay if I didn’t want to come.

He jumped into his car and I followed him in the second car, and we went towards the meeting point. I completely believed that this was a suicidal mission and we would not leave alive.

Snow was banked either side of the road, and hundreds of Taliban fighters armed with rocket launchers and heavy machine guns were posted along the road every 200 yards or so for two miles. ‘We were outnumbered,’ Muslem recalled.

They drove to a small post on a hill outside the town of Maidanshahr and Massoud sat down with the Taliban on the rooftop. His guards stopped 100 yards below the post. Only Shamsurahman was with him. The Taliban greeted Massoud with great respect, he recalled. It was Ramadan, the month when Muslims fast from dawn to dusk, and the evening prayer was already nearing when Mullah Rabbani, the deputy leader of the Taliban, finally began. Shamsurahman described the meeting:

He recalled the jihad and the sacrifices made by the people of Afghanistan to establish an Islamic system. He then criticised the mujahideen for failing to establish comprehensive security in Afghanistan. He also mentioned the Mujahideen government’s failure to comply with Islamic law, and complained that women were not wearing the veil, and also complained about the presence of communists in the government.

They stopped to pray the evening prayer behind Maulvi Zahir, one of the mediators. After the prayer, Massoud spoke. He concurred that Afghan people had fought jihad in order to establish an Islamic system of security throughout the country and the adherence of Islamic law. He said he adhered to its principles. He was placatory. ‘We do not have issues with your demands,’ he told them. ‘We all agree and want to help each other.’ But on specifics he did not yield. Mullah Rabbani demanded that every- one comply with the Taliban’s disarmament process, but Massoud refused, saying, ‘We are the government, so we should work together to disarm the rest of Afghanistan’s armed groups.’ The Taliban also wanted to clear the government of former communists – such as General Baba Jan, a Soviet-trained officer and a key ally of Massoud – and ban women from the workplace, which Massoud deflected. It was cold, and the time for breaking the fast at sundown was approaching. Massoud suggested that the talks should continue, and that next time the Taliban should come to Kabul.

He asked the Taliban leader to visit President Rabbani in the presidential palace in Kabul and advocated that, once disarmament was complete, all parties could go forward to contest elections, so the public could choose their leaders fairly. The meeting ended cordially, but a current of hostility was swirling.

Massoud told his commanders afterwards that he did not think the Taliban were their own masters. Indeed, during the meeting, Mullah Rabbani was urged by some commanders to take Massoud captive that day, according to a former member of the Taliban who was present at the meeting. Mullah Rabbani refused, saying, ‘We are not hypocrites, we are Muslims. It is not the work of a Muslim when you invite a Muslim and a mujahid brother and you deceive him. No way, I cannot do this!’ Mullah Rabbani sent an escort with Massoud to ensure that he returned to the government side safely.

Mullah Rabbani paid for his refusal. He was immediately recalled to Kandahar by the Taliban leader Mullah Omar, who demanded, ‘How much money were you promised by Massoud?’ Rabbani denied there had been any deal or exchange of money, but he was stripped of his vehicle, telephone, and other trappings of power, and told, ‘There is no space for you in the movement.’

Massoud learned of the threat to him on his way home. His intelligence operators manning the radios called to say they had picked up two radio intercepts from the Taliban ordering his capture. Massoud was lucky to escape with his life, his son Ahmad later told me.

But Massoud was undeterred. Just days after the Maidanshahr meeting, the Taliban seized control of Hekmatyar’s old base at Charasyab, expanding their hold on the southern approaches to the city. Massoud sent Shamsurahman and one of the elders, Maulvi Zahir, to see the Taliban at Charasyab. Mullah Rabbani was not there. They saw Mullah Borjan; he was in a testy mood, but he agreed to go with two others – Mullah Ghous and Abdul Wahid Baghrani – to Kabul to continue discussions. Massoud hosted the three Taliban commanders for two days, and together they agreed to convene a large bilateral council of religious scholars, who would decide the way forward. Members of the Taliban made several more visits to Kabul and met with President Rabbani among others, according to Shamsurahman, but all efforts to negotiate ended a month later when the Taliban entered a deal with the Hisb-i-Wahdat leader, Mazari, and then abruptly executed him.

I also went with an interpreter to meet the Taliban that year, and I found them hostile. They told me Massoud was a bad Muslim. The interpreter and I extricated ourselves as soon as we could and drove back to Kabul. I began to see that the Taliban were both belligerent and dangerous. Soon after in September 1995, the Taliban took Herat from Ismail Khan, killing hundreds of Massoud’s troops, who had been flown there in a last-ditch attempt to stem the advance. By June 1996, the Taliban were tightening their siege of Kabul.

I wrote in an article for The Times after a visit that year:

Kabul had plenty of problems, not only the rockets, which were killing and maiming people almost every day. Inflation was rampant: a meal for three in the best kebab house cost me 60,000 afghanis – $4 at the rate of exchange at the time – while a doctor or teacher made only 80,000 or 90,000 afghanis a month. Cases of deprivation were countless.

Despite the problems created by the Taliban, I detected a new optimism and self-confidence in Rabbani, who was running the Kabul government

– and Massoud’s great strength, his tireless perseverance to find a way forward, was on display. At the time, I wrote:

Rabbani may be President, but Ahmad Shah Massoud, although he holds no official post, is the real power behind the throne. If anyone can unite the Afghans – and it may be an impossible task – it is more likely to be Massoud than anyone else. He has a plan and the energy to pursue it. In the course of the next few days, two meetings, and a long talk, I watched Massoud trying to implement stage one of his plan: the formation of a coalition government, which would then draw up a constitution and hold elections.

His former arch-enemy, Hekmatyar, was, once again, proposed as prime minister, with defence and finance responsibilities thrown in for good measure. I suggested that that may be a risky if not reckless gamble. Massoud did not see it like that: echoing Stalin’s famous jibe about the Pope, he asked how many divisions Hekmatyar had. The answer by then was hardly any, while the political advantage to Massoud was considerable, I wrote:

Not only has the former favourite of the Americans and the Pakistanis been persuaded to change sides, but by doing so he has split the old and dangerous alliance with the northern warlord General Abdul Rashid Dostum.

One evening, on a terrace facing the snow-capped peaks of the Hindu Kush, overlooking the Shomali Plain where Mr Massoud once fought the Russians, I saw him deep in conversation with a group of Kandahari commanders – opponents of [the] Taliban – and a prominent member of the moderate Gailani Party, Sayed Salman Gailani, who was the Afghan Foreign Minister for a short time in 1992. Mr Gailani told me afterwards that there were few real differences between their two parties and he was confident that they could be overcome.

Mr Massoud, who works an 18-hour day, has been talking to most of the other parties as well. Only two, for the time being at least, are considered impossible bedfellows, the Taliban and General Dostum. But as Mr [Abdul Rahim] Ghafoorzai, his foreign affairs adviser and Deputy Foreign Minister, put it to me, ‘Mestiri [the former United Nations special envoy] made the mistake of trying to get a consensus. We are trying to get a majority of the political parties together in a coalition.’

A couple of days later, sitting in a garden fragrant with the scent of. . .

In the late 2010s, Sangin acquired the reputation among British troops of being the most dangerous town in Afghanistan. From the moment 3 PARA (the British army’s 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment) arrived in Sangin, its soldiers found themselves fighting for their lives to hold the district centre against successive waves of Taliban fighters determined to drive them out. In those four years, the British lost more than 100 men in Sangin, with many more wounded. But the Taliban never took the district centre.

At first, Massoud and Rabbani had welcomed the rise of the Taliban, approving of their promise to introduce law and order and rid the country of lawless banditry. Massoud and Rabbani even supplied support to the Taliban in the early days, and some Jamiat commanders had joined the movement. But Massoud changed his mind after a personal encounter with the Taliban.

In February 1995, with minimal protection, Massoud drove down to Maidanshahr, south-west of Kabul, to meet some of the Taliban leaders. The meeting came out of the Rabbani government’s early favourable contacts with the Taliban and was arranged by several Pashtun religious elders whose party, Harakat-i-Inqilab-i-Islami, was a prominent force in the Taliban. The elders also offered to mediate. Massoud agreed and asked Shamsurahman, a northern Pashtun Jamiat commander who was the military logistics chief for the Shura-i-Nazar, to join the delegation. The elders travelled to Maidanshahr to meet the Taliban and found most of the top leaders there: the deputy head of the movement, Mullah Rabbani, and the prominent military commanders Mullah Borjan, Mullah Khairkhwah, Mullah Ghous, and Abdul Wahid Baghrani – everyone but the supreme leader, Mullah Omar. Massoud’s envoys told them that Massoud wanted peace, to avert further fighting. Mullah Rabbani demanded to meet Massoud in person. When the delegation briefed Massoud the next day, one of his commanders, Registani, advised him not to go to an area under Taliban control, but Massoud was still keen, and replied that for the sake of peace he would ‘even go to Kandahar’.

The next morning, Massoud sent his senior officer, Ahmad Muslem Hayat, ahead with the elders to scope out the meeting place. Muslem found the Taliban uncooperative. On his return, Muslem met Massoud at the front line and warned him that it was a trap. He even evoked a historical precedent: the fate of the short-lived Tajik leader Habibullah Kalakani, better known as Bacha Saqao, ‘the Water Carrier’, who ruled Kabul for less than a year in 1929 and, as the story goes, was captured when invited to a meeting by his Pashtun opponents, and then executed.

‘I tried to convince [Massoud] not to go to this meeting,’ Muslem later wrote in a personal account of the meeting, ‘but my colleagues convinced him to go, as they claimed [the Taliban] were good people. He stayed quiet and did not tell us of his decision.’ Muslem recalled that Massoud then suggested they take a walk together.

As everyone waited and sat on the road, Massoud and I walked to a distant spot, and I did not know what he was going to say to me. As we walked, he stuck close to me, so the people behind could not see what we did. He asked me if I was armed and asked for my pistol. I was surprised at this question and told him that I had a Makarov and it was loaded with eight bullets, and he asked for an extra magazine. I gave him the pistol and told him I didn’t have an extra magazine, and then he turned to walk back toward the others. At this point, I was upset and started to question his actions and told him not to go forward with this meeting, because of past events with King Habibullah, who was killed in a similar fashion. I told him, ‘This is your last chance, because they will capture you and execute you.’ I kept trying to convince him, but he told me that he had made his decision and he had to go. I got a severe headache …it felt like my head was going to explode. He told me to stay if I didn’t want to come.

He jumped into his car and I followed him in the second car, and we went towards the meeting point. I completely believed that this was a suicidal mission and we would not leave alive.

Snow was banked either side of the road, and hundreds of Taliban fighters armed with rocket launchers and heavy machine guns were posted along the road every 200 yards or so for two miles. ‘We were outnumbered,’ Muslem recalled.

They drove to a small post on a hill outside the town of Maidanshahr and Massoud sat down with the Taliban on the rooftop. His guards stopped 100 yards below the post. Only Shamsurahman was with him. The Taliban greeted Massoud with great respect, he recalled. It was Ramadan, the month when Muslims fast from dawn to dusk, and the evening prayer was already nearing when Mullah Rabbani, the deputy leader of the Taliban, finally began. Shamsurahman described the meeting:

He recalled the jihad and the sacrifices made by the people of Afghanistan to establish an Islamic system. He then criticised the mujahideen for failing to establish comprehensive security in Afghanistan. He also mentioned the Mujahideen government’s failure to comply with Islamic law, and complained that women were not wearing the veil, and also complained about the presence of communists in the government.

They stopped to pray the evening prayer behind Maulvi Zahir, one of the mediators. After the prayer, Massoud spoke. He concurred that Afghan people had fought jihad in order to establish an Islamic system of security throughout the country and the adherence of Islamic law. He said he adhered to its principles. He was placatory. ‘We do not have issues with your demands,’ he told them. ‘We all agree and want to help each other.’ But on specifics he did not yield. Mullah Rabbani demanded that every- one comply with the Taliban’s disarmament process, but Massoud refused, saying, ‘We are the government, so we should work together to disarm the rest of Afghanistan’s armed groups.’ The Taliban also wanted to clear the government of former communists – such as General Baba Jan, a Soviet-trained officer and a key ally of Massoud – and ban women from the workplace, which Massoud deflected. It was cold, and the time for breaking the fast at sundown was approaching. Massoud suggested that the talks should continue, and that next time the Taliban should come to Kabul.

He asked the Taliban leader to visit President Rabbani in the presidential palace in Kabul and advocated that, once disarmament was complete, all parties could go forward to contest elections, so the public could choose their leaders fairly. The meeting ended cordially, but a current of hostility was swirling.

Massoud told his commanders afterwards that he did not think the Taliban were their own masters. Indeed, during the meeting, Mullah Rabbani was urged by some commanders to take Massoud captive that day, according to a former member of the Taliban who was present at the meeting. Mullah Rabbani refused, saying, ‘We are not hypocrites, we are Muslims. It is not the work of a Muslim when you invite a Muslim and a mujahid brother and you deceive him. No way, I cannot do this!’ Mullah Rabbani sent an escort with Massoud to ensure that he returned to the government side safely.

Mullah Rabbani paid for his refusal. He was immediately recalled to Kandahar by the Taliban leader Mullah Omar, who demanded, ‘How much money were you promised by Massoud?’ Rabbani denied there had been any deal or exchange of money, but he was stripped of his vehicle, telephone, and other trappings of power, and told, ‘There is no space for you in the movement.’

Massoud learned of the threat to him on his way home. His intelligence operators manning the radios called to say they had picked up two radio intercepts from the Taliban ordering his capture. Massoud was lucky to escape with his life, his son Ahmad later told me.

But Massoud was undeterred. Just days after the Maidanshahr meeting, the Taliban seized control of Hekmatyar’s old base at Charasyab, expanding their hold on the southern approaches to the city. Massoud sent Shamsurahman and one of the elders, Maulvi Zahir, to see the Taliban at Charasyab. Mullah Rabbani was not there. They saw Mullah Borjan; he was in a testy mood, but he agreed to go with two others – Mullah Ghous and Abdul Wahid Baghrani – to Kabul to continue discussions. Massoud hosted the three Taliban commanders for two days, and together they agreed to convene a large bilateral council of religious scholars, who would decide the way forward. Members of the Taliban made several more visits to Kabul and met with President Rabbani among others, according to Shamsurahman, but all efforts to negotiate ended a month later when the Taliban entered a deal with the Hisb-i-Wahdat leader, Mazari, and then abruptly executed him.

I also went with an interpreter to meet the Taliban that year, and I found them hostile. They told me Massoud was a bad Muslim. The interpreter and I extricated ourselves as soon as we could and drove back to Kabul. I began to see that the Taliban were both belligerent and dangerous. Soon after in September 1995, the Taliban took Herat from Ismail Khan, killing hundreds of Massoud’s troops, who had been flown there in a last-ditch attempt to stem the advance. By June 1996, the Taliban were tightening their siege of Kabul.

I wrote in an article for The Times after a visit that year:

Kabul had plenty of problems, not only the rockets, which were killing and maiming people almost every day. Inflation was rampant: a meal for three in the best kebab house cost me 60,000 afghanis – $4 at the rate of exchange at the time – while a doctor or teacher made only 80,000 or 90,000 afghanis a month. Cases of deprivation were countless.

Despite the problems created by the Taliban, I detected a new optimism and self-confidence in Rabbani, who was running the Kabul government

– and Massoud’s great strength, his tireless perseverance to find a way forward, was on display. At the time, I wrote:

Rabbani may be President, but Ahmad Shah Massoud, although he holds no official post, is the real power behind the throne. If anyone can unite the Afghans – and it may be an impossible task – it is more likely to be Massoud than anyone else. He has a plan and the energy to pursue it. In the course of the next few days, two meetings, and a long talk, I watched Massoud trying to implement stage one of his plan: the formation of a coalition government, which would then draw up a constitution and hold elections.

His former arch-enemy, Hekmatyar, was, once again, proposed as prime minister, with defence and finance responsibilities thrown in for good measure. I suggested that that may be a risky if not reckless gamble. Massoud did not see it like that: echoing Stalin’s famous jibe about the Pope, he asked how many divisions Hekmatyar had. The answer by then was hardly any, while the political advantage to Massoud was considerable, I wrote:

Not only has the former favourite of the Americans and the Pakistanis been persuaded to change sides, but by doing so he has split the old and dangerous alliance with the northern warlord General Abdul Rashid Dostum.

One evening, on a terrace facing the snow-capped peaks of the Hindu Kush, overlooking the Shomali Plain where Mr Massoud once fought the Russians, I saw him deep in conversation with a group of Kandahari commanders – opponents of [the] Taliban – and a prominent member of the moderate Gailani Party, Sayed Salman Gailani, who was the Afghan Foreign Minister for a short time in 1992. Mr Gailani told me afterwards that there were few real differences between their two parties and he was confident that they could be overcome.

Mr Massoud, who works an 18-hour day, has been talking to most of the other parties as well. Only two, for the time being at least, are considered impossible bedfellows, the Taliban and General Dostum. But as Mr [Abdul Rahim] Ghafoorzai, his foreign affairs adviser and Deputy Foreign Minister, put it to me, ‘Mestiri [the former United Nations special envoy] made the mistake of trying to get a consensus. We are trying to get a majority of the political parties together in a coalition.’

A couple of days later, sitting in a garden fragrant with the scent of. . .