next part >

At a certain age, nothing is more important than fitting in

The boy sits on the living room sofa, lost in his thoughts and

stroking the family cat with his fragile hands. His younger brother and

sister sit on the floor, chattering and playing cards. But Sam is

overcome by an urge to be alone. He lifts the cat off his lap, ignoring a

plaintive meow, and silently stands, tottering unsteadily as his thin

frame rises in the afternoon light.

He threads his way toward the kitchen, where his mother bends

over the sink, washing vegetables for supper. Most 14-year-old boys whirl

through a room, slapping door jambs and dodging around furniture like

imaginary halfbacks. But this boy, a 5-foot, 83-pound waif, has learned

never to draw attention to himself. He moves like smoke.

He stops in the door frame leading to the kitchen and melts into

the late-afternoon shadows.

He watches his mother, humming as she runs water over lettuce.

The boy clears his throat and says he’s not hungry. His mother sighs with

worry and turns, not bothering to turn off the water or to dry her hands.

The boy knows she’s studying him, running her eyes over his bony arms and

the way he wearily props himself against the door frame. She’s been

watching him like this since he left the hospital a few months before.

“I’m full,” he says.

She bends her head toward him, about to speak. He cuts her off.

“Really, Mom. I’m full.”

“OK, Sam,” she says quietly.

The boy slips behind his mother and steps into a pool of light.

A huge mass of flesh balloons out from the left side of his face.

His left ear, purple and misshapen, bulges from the side of his head. His

chin juts forward. The main body of tissue, laced with blue veins, swells

in a dome that runs from sideburn level to chin. The mass draws his left

eye into a slit, warps his mouth into a small, inverted half moon. It

looks as though someone has slapped three pounds of wet clay onto his

face, where it clings, burying the boy inside.

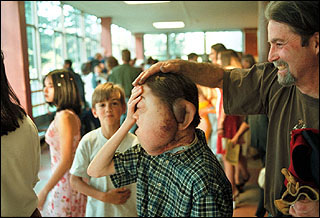

Sam Lightner at a meeting of his Boy Scout troop.

But Sam, the boy behind the mask, peers out from the right eye.

It is clear, perfectly formed and a deep, penetrating brown.

You find yourself instantly drawn into that eye, pulled past the

deformity and into the world of a completely normal 14-year-old. It is a

window into the world where Sam lives. You can imagine yourself on the

other side of it. You can see yourself in that eye, the child you once were.

The third of Sam’s face surrounding his normal eye reinforces the

impression. His healthy, close-cropped hair is a luxuriant brown, shaped

carefully in a style any serious young man might wear. It’s trimmed

neatly behind a delicate, well-formed ear. His right cheek glows with the

blushing good health that the rest of his face has obscured.

The boy passes out of the kitchen, stepping into the staircase

that leads to the second floor. A ragged burst of air escapes from the

hole in his throat—a tracheotomy funnels air directly into his lungs,

bypassing the swollen tissue that blocks the usual airways. He walks

along the worn hallway and turns into his room, the one with the toy

license plate on the door. It reads "Sam."

The Northeast Portland house, wood-framed with a wide front porch

and fading cream-colored paint, is like thousands of others on Portland’s

gentrifying eastside. Real estate prices have soared, but the Lightners

still need new carpets in every room and could use new appliances.

Although she’d rather stay home with the children, Debbie Lightner works

part time as a bank teller. The paycheck helps, but she really took the

job for the health insurance.

From upstairs, Sam hears 12-year-old Emily and 9-year-old Nathan

laughing. The kitchen, though, is silent. The boy figures his mother and

father are talking about him and this night. For months Feb. 3, 2000, has

been circled on the family calendar that hangs on a kitchen wall.

He grabs a small foam basketball and throws up an arcing shot

that soars across the room and hits a poster tacked to the far wall.

His mother made the poster by assembling family photographs and

then laminating them. In the middle is a questionnaire Sam filled out

when he was 8. He had been asked to list his three wishes. He wanted $1

million and a dog. On the third line, he doodled three question marks—in those oblivious days of childhood, he couldn’t think of anything else

he needed.

The morning routine around the family’s Northeast Portland house gets hectic when five Lightners line up for one bathroom, hunt for socks, eat breakfast and rush out the door. But Debbie Lightner still finds time for play with Sam as she challenges his decision about the shirt he’ll wear to school.

Finally, his mother calls out. His teeth are brushed, his face

washed. He runs his left hand through his brown hair, parting it to the

right.

He must imagine what he looks like. There’s no mirror to examine

his face.

In this boy’s room, there’s never been a mirror.

“Ready for this, Sam?” asks David Lightner, a

weathered jewelry designer who saves money by riding a motorcycle 25

miles to work. Sam nods his head and replies with a garbled sound,

wheezing and breathless, the sound of an old man who has smoked too long

and too hard.

“OK,” his father replies. “Let’s go.”

His sister and brother watch from the window as Sam and his

parents walk to a Honda Accord that has 140,000 hard miles on the

odometer. The boy gets in the back seat, and the Honda backs down the

driveway.

Just a few blocks from home, Sam senses someone looking at him.

After a lifetime of stares, he can feel the glances.

The Accord is stopped at a light, waiting to turn west onto

Northeast Sandy Boulevard, when a woman walking a poodle catches sight of

him. She makes no pretense of being polite, of averting her eyes. When

the light changes, the woman swivels her head as if watching a train

leave a station.

On school mornings, Sam rustles up his own breakfast, and his sweet tooth sometimes gets the better of him. His wholesome side might lead him to microwave a bowl of hot cereal. But he’s just as likely to top it with chocolate syrup.

Grant High School’s open house attracts more than 1,500 students

and parents. Even though they’ve come early, the Lightners must search

for a parking place. Sam’s father circles the streets until he finds one

nearly 15 blocks from the school.

The family steps out onto the sidewalk and walks through the dark

neighborhood. As Sam passes under a streetlight, a dark-green Range Rover

full of teen-age boys turns onto the street. A kid wearing a baseball cap

points at the boy. The car slows. The windows fill with faces, staring

and pointing.

Sam walks on.

Soon, the streets fill with teen-agers on their way to Grant. Sam

recognizes a girl who goes to his school, Gregory Heights Middle School.

Sam has a secret crush on her. She has brown hair, wavy, and a smile that

makes his hands sweat and his heart race when he sees her in class.

“Hi, Sam,” she says.

He nods.

“Hi,” he says.

The boy’s parents fall behind, allowing their son and the girl to

walk side by side. She does most of the talking.

He’s spent a lifetime trying to make himself understood, and he’s

found alternatives to the words that are so hard for him to shape. He

uses his good eye and hand gestures to get his point across.

Two blocks from Grant, kids jam the streets. The

wavy-haired girl subtly, discreetly, falls behind. When the boy slows to

match her step, she hurries ahead. Sam lets her go and walks alone.

Grant, a great rectangular block of brick, looms in the distance.

Every light in the place is on. Tonight, there are no shadows.

He arrives at the north door and stands on the steps, looking in

through the windowpanes. Clusters of girls hug and laugh. Boys huddle

under a sign announcing a basketball game.

Sam grabs the door handle, hesitates for the briefest of moments

and pulls the door open. He steps inside.

He walks into noise and laughter and chaos, into the urgency that

is all about being 14 years old.

Into a place where nothing is worse than being different.

* * *

The computer room in Sam’s house is out of main traffic patterns, and it’s a place where Sam can slip off into his own world. On the Internet, Sam is just another screen name in a chat room, where his words speak for themselves, unfiltered by his distorted voice or his appearance.

Years later she still wonders if it was something she missed,

some sign that things weren’t right. But it wasn’t until her seventh

month that Debbie Lightner learned something had gone terribly awry.

She struggled to sit up on the examination table. The baby, her

doctor said, was larger than it should be. Debbie watched him wheel up a

machine to measure the fetus. She felt his hands on her stomach.

“Something’s wrong,” the doctor said again.

He told Debbie he would call ahead to the hospital and schedule

an ultrasound. He laughed and told Debbie he just wanted to be sure she

wasn’t having twins.

The next morning, at the ultrasound lab, the technician got right

to work.

He immediately ruled out twins.

Then, a few minutes into the test, the technician fell silent. He

repeatedly pressed a button to take pictures of the images on the

monitor. After 30 minutes, he turned off the machine, left the room and

returned with his boss. The two studied the photographs.

They led the Lightners down the hall to a prenatal specialist.

Their unborn child, he said, appeared to have a birth defect. The

ultrasound indicated that the child’s brain was floating outside the body.

He had to be blunt. This child will die.

Some parents, he said, would choose to terminate.

No, Debbie remembers telling him. She and her husband were

adamant that they would not kill this baby.

On Sunday, Oct. 6, 1985, six weeks before she was due, Debbie

went into labor at home. David drove her to the hospital, and the staff

rushed her to the delivery room for an emergency Caesarean.

She heard a baby cry. A boy. The boy they’d decided to name Sam.

She passed out.

When she came to, she asked to hold her child.

No, her husband said. The boy was in intensive care. He needed

surgery.

David handed his wife two Polaroids a nurse had taken. A bulging

growth covered the left side of the baby’s face and the area under his neck.

”What is it?“ Debbie asked.

“I don’t know,” David said. “But he’s alive.”

When the Lightners arrived at the neonatal ICU, they were led to

an isolette, a covered crib, that regulates temperature and oxygen flow.

A nurse had written “I am Sam; Sam I am”—a line from Green Eggs and

Ham by Dr. Seuss—and taped it to the contraption.

Wires from a heart monitor snaked across the baby’s tiny chest.

He was fragile, a nurse said, and they couldn’t hold him.

The mass fascinated Debbie, and she asked if she could touch her

son.

The nurse lifted the cover of the isolette, and Debbie reached

down with a finger. The mass was soft. It jiggled. Debbie thought it

looked like Jell-O.

The nurse closed the cover.

Debbie and her husband returned to her room, and she climbed into

bed. She picked up one of the pictures her husband had given her and

covered the mass with her fingers to see what her son should have looked

like. He had brown hair and eyes.

She wept.

* * *

The temptation is to break ranks during a family portrait, and wave when a neighbor drives by. Still almost everyone stays in character, Nathan, 9, is a cutup who mugs for the camera. Emily 12, tries to stay dignified. Maggie, the vocal family dog, is uncharacteristically quiet, but David and Debbie are their naturally casual selves.

Tim Campbell, a pediatric surgeon known for tackling tough cases,

walked into the ICU and peered into the isolette. The boy had a vascular

anomaly. They were rare enough, but what this tiny infant had was even

rarer. The anomaly was a living mass of blood vessels. And it had invaded

the left side of Sam’s face, replacing what should have been there with a

terrible tangle of lymphatic and capillary cells.

The malformation extended from his ear to his chin. Campbell knew

there was no way to simply slice it off, as if it were a wart, because it

had burrowed its way deep inside Sam’s tissue. Doctors knew little about

such anomalies except that they were made up of fluid-filled cysts and

clots that varied in size from microscopic to as big as a fingertip.

Campbell gently pulled the baby’s mouth open. The mass swelled up

from below and wormed its way into his tongue, threatening to block his

air passage. He could barely breathe, and only immediate action would

save him. He asked a nurse to direct him to the Lightner room.

Campbell introduced himself, explaining the surgery. He didn’t

mince words.

“I’m going to be in there a long time,” the Lightners remember him

saying. “It’s risky. He’s little, and he’s premature.”

Campbell operated for six hours and removed 1 pound, 10 ounces of

tissue from under Sam’s neck. He operated a second time to remove bulk

above his left ear and to ease his breathing with a tracheotomy tube. But

there was no way, he told the Lightners, that he could safely remove the

mass on Sam’s face.

Campbell had sliced away a quarter of the infant’s weight. Baby

Sam, who weighed 5 pounds after the surgeries, spent three months

recovering in the hospital.

* * *

He was 3 when he first realized he was different. His father

remembers Sam running up and down a hallway when he stopped in midstride

and stared at his image in a full-length mirror. He touched the left side

of his face, almost as if to prove to himself that he was in fact that

boy in the mirror.

He cried.

His parents had been expecting this day. His father bent over and

took Sam by the hand. He led him to a bedroom off the hall. Debbie joined them. David lifted Sam onto the bed. And then

his parents told the little boy the complicated facts of his life.

Except for the deformity, Sam was normal in every way. But

everyone outside Sam’s circle of family and friends would have a hard

time seeing beyond the mass of tissue on his face.

And so it was.

A little girl grabbed her mother’s hand when Debbie pushed Sam,

in a stroller, onto an elevator. The girl stared at the little boy,

pointed at him and then loudly told her mother to “look at the ugly baby.”

Bystanders often assumed Sam was retarded. A woman asked Debbie

what drugs she had taken during her pregnancy. Strangers said they’d pray

for the boy. Others just shook their heads and turned away.

His parents went to another surgeon to see if he could reduce the

mass. He removed some tissue from behind Sam’s left ear but encountered

heavy bleeding and closed up. Even then, the incisions wouldn’t heal. Sam

bled for six weeks.

When the Lightners realized their son would have to live with his

face, they refused to hide him from the world. They took him to the mall,

to the beach, to restaurants. In Northeast Portland, where the Lightner

family lived, people talked about seeing a strange-looking boy. “That

boy,” they called him.

The Lightners enrolled Sam in the neighborhood school. Sam, his

breathing labored, caused a stir during registration. Teachers worried

about having the boy in their classes.

But he was an excellent student. He made friends, joined the Cub

Scouts and played on a baseball team. He tried basketball for a year, but

he fell easily because his head was so heavy.

When Sam turned 12, he told his parents that he wanted to change

his face. They took him to Dr. Alan Seyfer, an OHSU professor who chaired

the medical school’s department of plastic and reconstructive surgery.

What Seyfer saw made him leery.

The mass was near vital nerves and blood vessels that surgery

could destroy, leaving Sam with a paralyzed face. Hundreds of vessels ran

through the deformed tissue, and every incision would cause terrible

bleeding. Sam could bleed to death on the operating table.

Nonetheless, Seyfer, who spent 11 years as a Walter Reed Army

Hospital surgeon, wanted to help. And so he scheduled Sam for surgery in

June 1998. A month before he asked a friend, the chairman of the

plastic-surgery department at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, to

join him.

A week before the surgery, Seyfer and his partner examined Sam

one last time. They peered down his throat so they could study the mass

without having to make an incision.

They didn’t like the view.

That afternoon, Seyfer met with Sam and his parents and said he

had made an agonizing decision. The surgery was too risky. In good faith,

he could not operate.

The news crushed Sam. He realized he had always held out hope

that a surgeon would pull him out of the horrible spotlight that targeted

him every time he went out in public. But no. He was trapped.

Graduation from eighth grade is a big night for Sam—he wins the citizenship award and receives a huge round of applause from the crowd of parents and students. Sam’s father playfully tousles his hair on the way out of the auditorium as brother Nathan watches.

Sam Lightner pedaled his bike as hard as he could, but his family

zoomed ahead. His legs ached, and he panted for breath. Even his younger

brother could ride his bike farther and longer.

Most days during this spring 1999 vacation, Sam wanted to just

lie in bed and watch television.

And when he spoke, his family kept asking him to repeat himself.

No one—the desk clerk at Central Oregon’s Sunriver Lodge, the woman in

the gift shop—could understand him. He garbled his speech, as if he

were speaking with a mouthful of food.

But he wasn’t eating. At dinner, he sat with his family,

listening, picking at his food, waiting to go lie down on the sofa. Over

his protests, his mother took him into the bathroom and weighed him.

Five pounds, she said. He’d lost five pounds. But a later visit

to his pediatrician turned up nothing.

Sam woke up one morning in pain. He touched his face and found it

tender. The mass was growing. His mother gave him Advil, but the mass

continued to swell. Within a week, he couldn’t swallow the pill. He stuck

his finger in his throat. His tongue felt bigger. By the end of the week,

Sam cried continually.

A doctor removed a lump where Sam’s shoulder met his neck,

thinking the lump was pressing against a nerve. But the pain continued.

On Sunday, Aug. 8, 1999, Sam came downstairs from his bedroom. He

found his mother outside, sitting on the front porch. He walked out and

sat next to her, crying. His speech slurred, and he had to repeat

himself. The pain, he managed to tell her, had spread across the entire

left side of his face.

The next morning, at the hospital, nurses poked and probed his

face. He sat still while strange machines whirled about his head. And

then he waited while specialists reviewed the X-rays and CAT scans. They

found nothing.

Sam refused to go home. Someone, he pleaded, had to help him.

Doctors admitted him and ran more tests. Four days later, on Aug.

13, the mass awakened.

Pain racked Sam’s body. He tried to call for help but couldn’t

speak. With his fingers, he reached up. His swollen tongue stuck several

inches out of his mouth. He punched the button beside his pillow to call

for help.

He wrote in a notebook to communicate with nurses and doctors, a

notebook his mother would later store away with the other memorabilia of

Sam’s medical journey.

“I have no idea why. Since I was a baby. I was born with this.”

“When I cough hard, little capillaries burst and a little blood

comes out.”

“Don’t touch.”

“Please, it hurts.”

He held out his arm so nurses could give him morphine. They fed

him through a tube.

Then the door to his room opened, and a new doctor walked in. The

man asked Sam if he knew him. Sam shook his head.

“I’m Tim Campbell,” the doctor said.

He’d been making routine rounds when he spotted Sam’s name on the

patient board. Campbell hadn’t seen the boy since he’d operated on him

nearly 14 years before, the day after he was born.

Dr. Campbell thumbed through the reports at the nurses’ station.

He checked Sam’s chart. The boy weighed 65 pounds—he was wasting away.

Campbell pulled up a chair.

“How do you feel?”

Sam wrote in his notebook: “Anything to stop the headaches.”

“Anything else?”

“I really don’t think this is going to work out.”

“The doctors are trying.”

“Please try your hardest.”

“Hang in there, Sambo.”

“I’m in pain. It was really bad this morning.”

Campbell made a note to order more morphine.

“I hurt.”

And methadone.

“I’m tired.”

“Try to sleep.”

“Will it kill me?”

next part >