< previous part | next part >

Acceptance sometimes comes in the struggle to achieve it

Dr. Tim Campbell looked down into Sam Lightner’s face. The boy, he remembers thinking, was giving up. Unless something dramatic happened, he would die.

Dr. Tim Campbell, the Portland surgeon who operated on Sam shortly after his birth, was on routine hospital rounds when he encountered his old patient and resumed caring for him.

The 14-year-old lay motionless in his bed at Portland’s Legacy Emanuel Hospital & Health Center. His bloated face spilled across most of the pillow. His tongue protruded grotesquely from his mouth, and the swelling on the left side of his face wrenched one eye completely out of position. In late summer of 1999, the deformity he’d carried since birth had suddenly grown to life-threatening size, choking off his airway and esophagus.

Sam, Campbell remembers thinking in blunt medical

slang, was “circling the drain.” He’d seen the same look in children

battling terminal cancer. At a certain point, they accepted their

fate and surrendered to death.

The doctor hurried back to his office, rummaged

through his desk drawers and pulled out a slim blue book, a list of every

pediatric surgeon in North America. He flipped through the pages.

Campbell paused when he reached the résumé of Dr.

Judah Folkman, a cancer researcher he’d met 30 years earlier when they

were both young surgeons. Folkman’s research team had controlled tumors in

mice by stifling the growth of the blood vessels that supplied

them, causing a national stir and overwrought speculation that a cancer

cure was at hand.

Folkman planned to test his technique on humans for

the first time in May 1999. Campbell considered the fact that a wild

excess of blood vessels had created Sam’s deformity. Maybe, he

thought, Folkman’s strategy would work on the boy.

But Folkman, besieged by more than a thousand

desperate cancer patients a week, is fiercely protective of his time. He

grants no interviews. A secretary screens all calls.

Campbell punched in the telephone number listed in

the blue book, hoping Folkman might grant a favor to an old friend. The

secretary put him on hold. Then Folkman came on the line.

His response was discouraging. Sam’s malformation

was fully formed, and his method worked only on growing tumors. But

Folkman suggested Campbell call a pediatric surgeon who worked for

him as a research fellow. Campbell scribbled out a name: Jennifer

Marler.

She was a member of the Boston’s Children’s

Hospital Vascular Anomalies Team, which treated malformations just like

Sam’s. Pleas for help deluge that team, too, and the surgeons can respond to

only a fraction. But when Campbell reached her, Folkman’s name

provided instant access.

Marler suggested that Campbell take some

photographs of Sam and send them along with the boy’s medical file. Campbell

should address the package to her to make sure it didn’t get lost in the slush

pile.

The best she could offer was that she’d take a look.

* * *

Sam Lightner turned his head and stared straight

into the camera while Campbell photographed his face. After Campbell left

the hospital room, a psychiatrist walked in, pulled up a chair and began

asking questions. Sam scribbled his answers in the notebook he

used to communicate.

Then Sam asked a question.

“Why is this happening?”

The psychiatrist had no answer. Instead, he asked another

question. Tell me how you feel about life, Sam remembers

him saying. Is life unfair?

How stupid, Sam thought. His tongue was sticking

three inches out

of his mouth. He couldn’t eat. His left eye bulged

abnormally, reacting

to pressure that seemed to build each hour. An IV drip line

ran into his

arm and pumped him full of drugs: morphine, methadone,

Celebrex and nortriptyline—a combination of painkillers,

anti-inflammatories and

antidepressants. None of them helped. No one could tell him

what was wrong.

Is life unfair?

“Sometimes.”

And then the swelling receded. Doctors couldn’t

explain why, but the sudden eruption died down as mysteriously as it had

come to life. On Sept. 2, 1999—after a month long hospital stay—Sam went

home.

But everything was different. Physically, Sam was a shell. He had

lost 17 pounds and was down to 63 pounds. He could not

speak. And the battle with the malformation had scarred him. His mother

remembers a listless child who wouldn’t stir from bed.

* * *

On Nov. 15, 1999, doctors determined Sam was

healthy enough to get back into his old routine. When he returned to Gregory

Heights Middle School, however, something had changed. All the talk in the

hallways was about high school—girls, dances, sports. Being popular.

Life as Sam Lightner knew it was ending. All his classmates were

obsessed with how they looked and how they fit in. But for

Sam, the issues every young teen faces were magnified a

thousandfold. He was moving out of the cocoon of familiarity that kept him among

family and longtime classmates, who could see past the disfiguring

mass he carried on his face. He was moving into a world of judgmental

teen-agers and he would carry with him a terrible handicap, a face

drastically shortchanged of its ability to reach others with a subtle expression, a

slightly raised eyebrow, a flicker on the edge of his mouth. He was

being cast among strangers who would turn away from his alien features

so fast that they would miss the boy behind the mask.

Like all teens, Sam’s perception of how others saw

him would determine how he saw himself.

And when strangers looked at Sam, they first

fixated on the left side of his face, a swollen mass that looked like a pumpkin

left in the fields after Halloween. His left ear was even more

abnormal, a purple mass the size and shape of a pound of raw ground beef. His

jaw, twisted. His teeth, crooked. His tongue, shoved to the side. His

left eye, nearly swollen shut.

When he walked to school each morning, he stopped

at the crosswalk on Northeast Sandy Boulevard and watched

passengers in cars and buses stare at him. When he walked through the

neighborhood, he heard laughter and comments.

Once, a neighbor boy led his friends over to Sam’s

house and knocked on the front door so the others could see Sam’s

face.

* * *

In late August, a thick envelope arrived in Dr.Jennifer Marler’s

office. She noticed it was from a Dr. Tim Campbell, an

unfamiliar name, and tossed it aside. At the end of the day, after a brutal

round of surgery, clinics and lab research, she was about to head

home to her husband and three children when she spotted the envelope.

She dropped into her chair, grabbed it, ripped it

open along one end and dumped the contents onto her desk. She started with

the medical report: Patient has lymphaticovenous

malformation of the left side of face and neck. Condition was diagnosed

prenatally. Involvement of the airway necessitated a tracheotomy.

Difficulty swallowing necessitated a gastronomy tube. Malformation has

grown to the point of orbitaldystopia. In all other areas

of life, though, the patient has developed normally.

She remembered—the Portland boy.

She searched through the paperwork and foundseveral photos. She

picked one up and held it between her fingers. The photograph haunted Marler.

The boy lay in a hospital bed, staring at the camera with

pleading eyes. He looked like one of the children featured

in ads aimed at raising money to help poor kids overseas.

Marler scanned the reports. The kid was on a

morphine drip, diagnosed as clinically depressed.

Marler was 38 and had been a doctor for 11 years.

Outside of a textbook, she had never come across such a profound facial

deformity. He was the saddest-looking child she’d ever seen.

And she had seen many. A score of photographs hang

on her office wall, the faces of children who have set the course of

Jennifer Marler’s life. Some of the images show children she successfully

operated on, relieving them of the deformities that robbed them of their

futures. Others tell sadder stories, reminding her of children who

died from their abnormalities or who took the risk of surgery and didn’t

survive.

Marler picked up the telephone and spoke with the

nurse who scheduled weekly team conferences for the Vascular

Anomalies Team. During the meeting, doctors discuss cases and decide whether they

want to tackle them. The nurse said the next chance to present a case

would be Sept. 22, 1999, just three weeks away.

She decided she’d present Sam Lightner’s case and

argue that he be brought to Boston. First, though, she had to get the

facts down cold.

She picked up the telephone again, called her husband,

apologized and told him to have dinner without her. She talked to her

three young daughters and told them Mommy had something important to

do.

* * *

The team met Wednesday evenings in the surgical library. Members,

fellows and residents gathered around a 15-foot-long oak

table, nibbling cookies and sipping soft drinks.

Everyone found a seat, the lights dimmed and the

patients’ images appeared, one by one, on an overhead screen. The team

members flipped through paperwork, scanning each patient’s medical history.

They spoke in short, clipped sentences, rife with medical jargon,

challenging one another, looking for potential problems that might rule out

surgery.

Marler remembers studying the paper in front of

her. Nineteen children were up for consideration. Fewer than half would

be chosen.

The team moved quickly: The agenda included an 8-month-old girl

from Argentina. A 3-year-old girl from Italy. A 9-year-old

boy from Minnesota.

Sam Lightner was next. His picture—the one Dr.

Tim Campbell had taken—flashed on the screen.

“Who is he?” someone asked.

Marler recalls choosing her words carefully. She

wanted to make sure the team knew something of the boy’s life. He was in

pain, she says she told them. Without hope. The disfigurement severe.

Although the center takes some of the most difficult cases in the

world, Marler knew Sam Lightner presented major problems.

Behind her, she heard papers rustle as the team

read his medical history. They quickly zeroed in on those risks. They

hesitated. Before making any decision, the team members wanted more

information.

Next case.

Marler scheduled Sam for the Nov. 3, 1999, meeting. Again the

answer was no.

At the Nov. 10 meeting, she tried again, focusing not on the

entire team, but on Dr. John Mulliken, the surgeon who

directs the Vascular Anomalies Team and a researcher who’s trying to

figure out the causes of defects such as Sam’s. Mulliken lectures at

hospitals around the world and co-founded the International Society for the

Study of Vascular Anomalies. He’s written 185 scientific articles,

40 book chapters and two complete books.

The way Marler saw it, a team of doctors would have

to operate on Sam. And Marler wanted to be on the team.

At this meeting, she spent an unusual 30 minutes

arguing her case, knowing this was her last chance. She studied

Mulliken, an impatient man, as he reviewed the files. She knew what he

was thinking—the horrendous bleeding, and the tangle of nerves in the

mass. If Mulliken damaged one, the boy might lose the ability to

speak, to close his left eye or to smile.

She appealed to Mulliken’s pride and compassion. No

other surgeons, Marler remembers telling him, believe they can

fix this.

She watched Mulliken, Sam’s last hope.

The projector’s motor hummed. Sam Lightner’s face

peered out into the room. Mulliken looked up at that face.

Bring him to Boston, he said.

* * *

Sam, on his first commercial airline flight, checks out a map and discusses it with his mom while their MD-80 carries them across the country to Boston, where Sam will meet the surgeons at Children’s Hospital.

The visit to Children’s Hospital includes a long round of appointments with different doctors In one waiting room, Sam entertains himself by spinning in an office chair while his parents mark the hours.

On April 7, 2000, Sam Lightner and his parents walked three blocks from their Boston hotel to Children’s Hospital. The

Lightners silently rode an elevator to the third floor, where a

smiling receptionist waved them over and took the Lightner file.

Sam found a seat and flipped through a stack of magazines. He caught the eye

of a woman sitting across from him. She turned away. Sam saw her

whisper something to a woman sitting next to her before both turned back to

stare.

“Samuel Lightner,” the receptionist called.

A woman led them down a hallway to an examination room. Sam climbed onto the table. A few minutes later, the Lightners

heard a soft knock.

She stood 5 feet 7 inches tall and wore a white doctor’s smock

over a long black skirt with matching black hose and shoes.

Her brown hair was cut in a pageboy. “I’m Dr. Marler,” she said.

She sat down on a doctor’s stool, tugged on her

glasses and fiddled with a string of pearls that lay across her white

and blue-striped blouse. “I’m so glad to meet you,” she told

Sam. A flush spread up his neck.

Debbie Lightner dug through her purse and handed

Marler a picture taken shortly after Sam’s premature birth. Marler stared at

the image of the tiny infant. “Boy,” she said, “you were a little

peanut.”

The Lightners explained Sam’s medical history—the

emergency surgery right after his birth, the ear surgery that led to

six weeks of persistent bleeding and the reluctance of other surgeons to

even attempt cutting away the main mass of tissue. Marler took notes,

interrupting occasionally to ask a question or to look at additional

photos.

“I think you’re in the right place,” she continued.

“Dr. Mulliken is both a craniofacial surgeon and a specialist in vascular

anomalies. That makes him the right man for the job.” She swiveled to

face the examination table.

“So let’s take a look, Sam.” She patted his knee. He smiled.

“What grade are you in now?”

“Eighth,” he said, in his raspy voice.

Marler ran her fingers across the mass, sizing it up. She sighed.

Sam’s father cleared his throat. “He’s going into the ninth

grade,” David Lightner said. “He wants the size of his head

made smaller. He’s a little bit more concerned about his appearance now.”

Marler patted Sam on the shoulder. “I can understand that, Sam,”

she said. “I’ll bring in Dr. Mulliken and our cast of thousands. On this

one, we’re going to need everyone’s opinion.”

She walked out, closing the door after her.

“You’ve been waiting for this a long time, haven’t you, Sam?” Debbie Lightner asked her son.

“Nervous?” his father asked.

“I’m just hoping.”

The door opened, and Marler walked back in, followed by six

doctors who formed a semicircle around Sam. A man wearing a

bow tie with blue and red polka dots stepped forward.

“Hi, Sam. I’m Dr. Mulliken. Nice to see you.”

He perched on the examination table next to Sam. He

took the boy’s head in his hands as if holding a basketball and

moved it gently, running his fingers from one side of the face to the other.

He frowned. All the blue veins showing through Sam’s waxen skin worried

him.

“Oh, boy,” he said. “There’s a lot of venous component there.

This is an incredible overgrowth.”

He released Sam’s head and climbed off the examination table. He

stepped back two feet and crossed his arms, looking like a

sculptor studying a block of granite. He moved to the left. The

semicircle moved with him. Back to the right. The other doctors shuffled

into place.

Mulliken ran his hands over his face. He groaned.

Marler jumped in. “I think he has very good facial

nerve function.”

“Smile, Sam,” Mulliken commanded.

He sighed again. “OK,” Mulliken said. “Let’s write down some things.”

That was what Marler had waited eight months to hear. She smiled, sat on a stool and opened her notebook, ready to send off

instructions on what Mulliken needed to know about the inside of Sam

Lightner’s head.

“I want Reza to look down the trach and see what’s

going on there,” Mulliken said, asking one of his colleagues to peer

down Sam’s airway. “Send him to AP for a Panorex. Find a CP and get

pictures downstairs. We’re going to have to decide what’s going on

in terms of flow, and if there’s anything we can do to make it easier.” He looked at Marler.

“Got all that?”

“Right,” Marler said.

Mulliken boosted himself back onto the exam table.

He scooted up next to Sam as if he were the boy’s grandfather. He put his

hand on Sam’s knee.

“What bothers you the most?” he asked. “If you had

one thing you wanted, what would that be?”

Sam shrugged. He stared at his hands, folded in his

lap.

“Should I give you some choices?” Mulliken asked. “Some multiple choices?”

Sam responded with a barely perceptible nod.

“Our goal will be to make you look as symmetrical

as possible, to balance out your face,” he said. “A Picasso is a great

painting, but no one wants to walk around with one for a face. We have many

things to talk about: Making your ear smaller, the tongue movement, the

eye. The neck’s pretty good.”

He put his arm around Sam’s shoulder. “What do you

want, Sam?” he asked quietly, as if the room were empty except for the two

of them.

Sam bowed his head and stared at his hands.

“Well, you’re really down to the choice of two

things,” Mulliken said. “We can focus on the face or the ear, but we can’t do

both at the same time. If we get the face smaller, the ear will look

bigger. Frankly, I just don’t know. The face is tough, very tough. Lord, I

just can’t imagine...”

Sam raised his head. He looked deeply into

Mulliken’s face with his one good eye. “I want to fit in,” he said in his raspy

whisper. “I want to look better.”

Mulliken nodded, his features softening. He pulled

the boy a little closer. “I can understand, Sam.”

David Lightner, standing against the back wall,

pushed his way through the semicircle until he faced Mulliken, who dropped

his arm from Sam’s shoulders and faced the father. “His goal?” Lightner

said. “Well, Sam’s 14 years old. Like you put it, he’d like a more

symmetrical face. I’m ambivalent. I understand the risk of the whole thing.

But this is something Sam wants. We’re supporting him.”

“OK, Dad,” Mulliken said. Then he swiveled on the

table and faced the doctors.

“I think it will be reasonable to focus on this

huge area on the side of his face,” Mulliken said. “It’s no-man’s land, and

it will be hard to work in that area. The problem’s going to be

finding the facial nerve branches and separating them from the malformation.

They look exactly alike.”

Mulliken slid off the table and paced. He shook his

head, as if he were having an argument with himself. “The bleeding.

Boy! When you are dealing with a pure lymphatic tissue malformation, bleeding

is just an annoyance. But if you have these venous components, which

he has, it’s more than a problem.”

He smiled. “But Sam, I’m going to try.”

The goal, Mulliken told the room, was to get the

mass on the side of Sam’s face down to the bone. If Mulliken could eliminate

the mass, Sam could return to the hospital for more surgery to reshape

the bone. That surgery would be much easier.

Dr. Jennifer Marler (left) acted as Sam’s persistent advocate, urging her colleagues to bring him to Boston. There, Dr. John Mulliken got his first look at the Portland boy.

“Another operation?” Debbie Lightner asked. “The

insurance company’s going to really love us.”

Mulliken broke through the semicircle and stopped

in front of her. “Listen,” he said, “you show that insurance company

photographs of this boy and there won’t be a dry eye in the house.”

The Lightners looked at each other.

Mulliken moved aside so they could look at Sam.

“Sam?” his father asked.

Sam nodded, more firmly this time.

Mulliken moved back to his patient. “This is going

to be tough. We’re in for a rough time in the operating room. It’s going

to be a microscopic dissection, and we’re going to need a team.”

He looked around the room. “Dr. Marler, me and one

or two others.”

He stepped back once more to look at Sam. “His face

is going to be swollen for a long time,” Mulliken said. “By the time he

goes to school, though, he should look considerably better. Push me

to the wall, and I’d like to think we could make it 50 percent better.”

“Sam,” he asked, “is this something you really

want?” Sam nodded. Mulliken patted the boy on the shoulder.

“Let’s schedule for July,” he told Marler.

Sam’s father cleared his throat. “From seeing him

in person, is this something you want to do?”

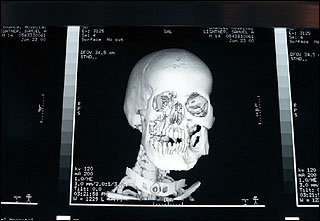

3-D CAT scans revealed the extent of the bone deformity that lies beneath the tissue mass on Sam’s face. The shape of the bone means that Sam’s image will remain distorted even if the tissue mass is removed, although surgeons think they can straighten the bone in a later—and much simpler—operation.

Mulliken frowned. “Well ...”

“I’m being blunt,” David said. “We have to know.”

Mulliken sat on the exam table again. “I don’t know

if ’want’ is quite the right word,” he said quietly. “I think that we

can do it.”

He ran his hands over his face. “I know we can do

it,” he said. “I wish I could make him perfect. All plastic surgeons

search for perfection, just like Michelangelo. I can’t give him

perfection.”

He hoped he could remove a large amount of tissue

from the side of Sam’s face. But he also knew the underlying bone would

remain seriously misshapen. When the world looked at Sam after the

first surgery, it would still see an extraordinary deformity. But

removing the tissue was the necessary first step to dealing with the

bone.

“Dad, I’m bothered that he has to live with this

mass,” Mulliken said. “Everyone should have the right to look human.”

* * *

Doctors worry about the nerve function in Sam’s face, and they check carefully to see how his deformity has affected his ability to feel and move.

The giddiness the Lightners felt vanished almost as

soon as the jet roared down the runway at Logan International Airport

and headed west, back to Portland, back to reality. Once home, David

and Debbie went back to work, and Sam returned to eighth grade.

Sam’s mother took Sam to register at Grant High

School. An administrator walked in, noticed the Lightners sitting

outside the counselors’ office and stopped. He introduced himself and

shook Sam’s hand. He turned away from the boy, as if Sam were deaf. He

told Debbie that Grant had a great special-education class for mentally

retarded students.

Her son, he said, would love it.

* * *

The telephone rang in the Lightner home. Dr.

Jennifer Marler told Debbie Lightner that surgery was scheduled for July 6.

Having a date, something to put on the calendar, made it real. And

frightening.

After dinner, the Lightners called their children

together. Sam sat at one end of the dining-room table, his father at the

other. In between were Debbie, Emily, 12, and Nathan, 9. The family

cat, Alice, jumped onto the table.

David Lightner played with a pencil, turning it end

over end. “I wanted to discuss how this is going to affect us,” he said. “We’re up in the air about whether we should do it. Mommy talked with

Dr. Marler for quite a while. There are dangers, but Dr. Marler said if

Sam was her child, Dr. Mulliken would be the man.”

David fiddled with a magazine. “There are some

things that could happen,” he said. “We have to be honest about that.”

“Like what?” Nathan asked.

“If some of the nerves are damaged, Sam’s face

could droop,” his mother said. “He’d be paralyzed on that side.”

“You mean he wouldn’t feel it?” Emily asked.

“Right.”

No one looked at Sam.

“He might bleed a lot during surgery,” his mother

said. “They think they can control it, but you never know. I think Dad

just wanted to have it all out on the table for everyone to talk about one

last time.”

David Lightner shifted in his chair.

“Now that we’re 3,000 miles away,” he said, “it puts a different spin on it. It’s more complicated sitting here.”

Debbie touched Sam’s arm. “Sam, do you still want

to do this?”

Sam nodded.

“I want to hear it.”

“Yes,” Sam said, firmly.

“It’s your decision,” his father said. “That’s the

deal. If I felt something was wrong, I’d intervene. I don’t sense

that. But I have to be honest, it scares me a little bit.”

“Me, too,” Nathan said.

“Me, too,” Emily said.

“I worry about the potential damage to him,” said

David. “As it stands, he’s Sam. He is who he is.”

“He’ll look different,” Emily said. “Sam is Sam.”

“He is who he is,” said David. “We don’t think

anything’s wrong with him.”

David leaned forward, arms on the table, and stared

across at his son. “Any doubts, Sam?” he asked. “If you say ’no,’ we call

and cancel right now, date or no date.”

“I’m a little nervous,” Sam said. “But I like the

doctors.”

“Well, it scares me,” his father said. “It’s the

unknown. Here we have the situation that Sam deals with. It’s the known.

It’s not ideal for him because of his face. His face freaks people out.

But it’s a known property. And it’s a little bit scary to risk everything

because the world doesn’t accept his face.”

“Dad, I’m sure,” Sam said. “Look what happened at

Grant.”

His father bowed his head.

“That’s what people think about him,” Debbie said. “They think he’s mentally defective.”

Sam leaned forward and mustered all his strength.

“I want to do this,” he said.

David placed both hands on the table.

“We are fearfully and wonderfully made,” he told

his family. “And very fragile.”

He sighed.

“All right,” he said. “It’s a go.”

< previous part | next part >