Dorothy Yahtin spotted the glow of the Simnasho Longhouse, cars still in the parking lot, and limped toward the light. The rugged hills of the Warm Springs Reservation, flecked with sage, stretched toward the dark horizon.

Her hands were freezing in the late November chill. She remembers numbly opening the door and stumbling in.

The tribal chairman and his family, gathered for dinner on the 2002 Thanksgiving weekend, looked up.

Dorothy’s long black hair hung around her battered face. A purple bruise, vivid in emergency-room photos taken later, circled her swollen left eye. Her upper lip split over her sheepish smile. She smelled like warm beer.

Please, she said, can you give me a ride? Please. Just to the highway.

She had no money, no driver’s license, no car. Her eyeglasses lay where they had been knocked from her face during a fight with her boyfriend the day before. The 35-year-old mother of five, a descendant of chiefs, medicine healers and a famed 19th-century U.S. Army scout, had hitchhiked 23 miles along an icy, isolated highway with hairpin curves and no shoulders, unable to see beyond a few feet. She planned to hitch another 85 miles west to Portland.

A friend in the longhouse led Dorothy out to a car in the parking lot. She drove Dorothy south, down the snaking narrow lanes of the reservation’s Highway 3 toward the town of Warm Springs. They passed the Simnasho Cemetery, where Dorothy’s mother, sister and brothers lay, dead of diabetes, suicide and murder. They passed Dorothy’s single-wide mobile home, standing as she’d abandoned it five months earlier. They passed the towering maples and pines that hid the house where Dorothy’s children lived with their grandfather.

Cecil was a slender 11-year-old with huge black eyes. He could box, but he liked to draw better, sketching eagles, horses, dinosaurs and Muhammad Ali. When he was sad, he fell totally silent, sometimes for hours.

Chelsey was a giggly 12-year-old named for her grandfather, Chesley. She was an A student and accelerated reader who carried one book with her everywhere she slept—a peeling scrapbook packed with photos of her family. She could serve a volleyball with unconscious grace and stroke through the rough Columbia like an otter.

Sonny was a shy, sensitive 14-year-old who protected himself with the tough-guy shell. The skateboarder who dreamed of one day working as the golf pro at Kah-Nee-Ta, the tribes’ resort.

They lived with Dorothy’s father, Chesley Q. Yahtin Sr. Nobody in the house had seen Dorothy for weeks. But that wasn’t unusual—she’d been disappearing most of their lives. Sonny had been in his grandfather’s custody since he was found as a toddler abandoned and hungry in a pickup. Chelsey couldn’t remember a birthday party her mother had attended sober. Cecil had once driven his mother away from a family fight by using a screwdriver to start her old car.

Dorothy’s fourth child, 8-year-old Amelio, born while she was using cocaine, had been placed permanently with guardians.

Her fifth, a playful 6-year-old named Marcus, lived with his father in the town of Warm Springs.

Chesley Q. Yahtin Sr. has lost six of his sons and a daughter to accidents, suicide and murder, and now they all lie in the Simnasho Cemetery. “My life is combat,” the 72-year-old Korean War veteran said. “My whole life is combat.”

The car carrying Dorothy drove on, to the outskirts of Warm Springs where Dorothy collapsed on a friend’s couch. A few days later, she called her dad.

Chesley, 72, said he’d be right there. Chesley and his namesake, Chelsey, climbed into his white Honda and drove south across the open country where wild horses grazed and ghostly trees from the latest wildfire lay like fallen warriors.

Dorothy climbed into her dad’s car, and he pulled onto U.S. 26. But instead of heading north to Simnasho, he turned southeast and drove to Madras, to the Greyhound bus station. He reached into his pockets and gave her every cent he had.

Go to Portland, Dorothy, he said. Get into treatment. I cannot do this any anymore.

* * *

Chesley Q. Yahtin Sr., is a Warm Springs Indian, a Sahaptin language speaker of the mid-Columbia bands whose ancestors have lived in Oregon for at least 10,000 years. He wore his long silver hair tied back, silver feather earrings and a baseball cap that said “Proud Warrior.” Hundreds of Native Americans shopped in nearby Madras, but Chesley’s heritage stood out. When Chesley walked by, a small boy blurted out, “He’s a real Indian.”

He had the Indian history, too, a window into the sorrow of the Warm Springs Reservation, a piece of high desert where three tribal cultures were driven like refugees onto the harsh plateaus of Central Oregon.

The river Indians had been one of the world’s most stable, prosperous societies. Families passed their culture from generation to generation, an unbroken chain that stretched through millennia.

Chesley’s ancestors had fished at Celilo Falls and gathered food from the Blue Mountains nearly to the Oregon coast until 1855, when the bands ceded their ancestral lands in exchange for land where, Gen. Joel Palmer promised, “no white man can come.”

But white men did come. For nearly 90 years, they separated reservation children from their parents and confined them to a military-style boarding school where their braids, their buckskins, their foods and their religions were taboo. The federal government intended boarding schools to change the Native American family forever—and they did.

Separating children from their parents destroyed patterns of nurturing and discipline, pinched off native languages and erased many of the community’s own social controls. Teachers sent children who excelled off the reservation, convincing Indians that doing well in school meant separation from tribe and family.

Chesley’s grandfather hated the boarding school so much that when white workers raided the Celilo Falls fish camps for Indian children, he hid the boy. Chesley grew up hunting and fishing in a centuries-old cycle of seasons and the Washat, the Seven Drum religion, in balance with the Earth and the unseen world. By 1941, when he was 10, he could survive a week alone with a .32-20 rifle. Then, he recalls, an Indian policeman on horseback saw their campfire smoke and dragged the boy off to boarding school.

Chesley Yahtin joined the Army and wound up as a combat medic in Korea. Wounded twice, he was left so psychologically scarred he considered suicide. “But I can’t do that to them,” he said, noting the grandchildren he is fighting to raise.

By 11, Chesley’s head was shaved and he was living in a dormitory in downtown Warm Springs where, he says, he was whipped for speaking the only language he knew and marched to the Presbyterian church. At 18, when he was finally set to start high school in nearby Madras, he fled to the one place he figured he could make it in the white world—the U.S. Army.

His grandfather never got over it. The government had, the old man said, knocked the Indian right out of him.

When Chesley got out of the Army and returned to Warm Springs, he married twice and fathered 13 children. Seven of his children died young—of accidents, suicide and murder. One son was beaten to death. Another was hit while walking on U.S. 26. His wife, Amelia, died in 1992 of diabetes. She was 53.

Extended families have always shared child-rearing in Native American communities across the country. But parents such as Dorothy played a key role in that collective responsibility. Now, in the Yahtin family, like so many on the reservation, the parents were missing. The chain that connected 500 generations of mid-Columbia Indians had been broken.

Dorothy’s sister Minnie had gone to college and created a stable home for her four children. Her brother Timothy was raising a daughter in Washington state. But others of their generation were dead, in prison, or—like Dorothy—drinking.

Chesley Yahtin rose at 4 a.m. to grade roads and plow snow to support his children’s children. He bought them contact lenses, skateboards and bedroom furniture, took them to the dentist, threw their birthday parties, held them when they were sick. But he was slowing down. What would happen when he was gone?

Children are precious, the tribal grandmothers taught. Gifts from the Creator. If you are careless with the children, the Creator will take them back.

* * *

When Dorothy’s bus arrived in Portland, she reported to the Native American Rehabilitation Association of the Northwest. The rehab center put her on a waiting list for residential treatment, placed her in a motel and signed her up for regular meetings.

Chesley and the children visited her about two weeks before Christmas. He spoiled them all Christmas shopping at Lloyd Center and then headed back to the reservation with the kids.

Dorothy remembers that the moment they left, she felt edgy, distracted, ugly in her own skin. She had a few dollars from the confederated tribes’ annual bonus to enrolled members. She could grab a beer. She pulled on a sweater and caught a bus downtown.

Bud Ice, Crown Royal, amber waves of no pain. She walked from bar to bar buying beer, shots, $20 packets of cocaine from street dealers, up and down Burnside from the paneled darkness of Dugo’s to the Shanghai on Broadway. Friends said she gave all her money away in $1 bills to Mexican laborers. She lost days.

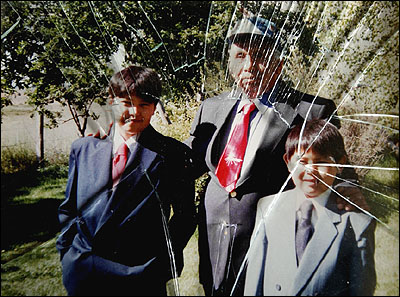

A shattered glass frame holds a family snapshot of Chesley Yahtin and the two grandsons he has raised since their earliest years, Cori (left) and Dorothy’s oldest son, Sonny.

She came to on Dec. 16, 2002. She remembers wanting to die.

Why not? Her sister Idelia had stepped in front of a train. Her brother Elliott had hanged himself in the Jefferson County Jail. Dorothy herself had swallowed a bottle of painkillers two years earlier. Friends found her just in time.

She reached in her bag, opened a bottle of Tylenol and swallowed every one.

She also remembers touching a small black Bible that a street preacher had handed to her at Pioneer Courthouse Square. Inside was a telephone number. She called it collect. A van pulled up, and the street preacher drove her to the Hooper Detoxification Center, a two-story brick building on Northeast Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. The staff took her to the hospital, where emergency treatment kept her alive.

Seven days later, she left detox and climbed the stairs of an old school building at the Native American Rehabilitation Association’s center just west of Portland.

It was her fourth inpatient treatment in a decade.

Dorothy took a deep breath.

She remembers feeling afraid. To fail again, to face her father, mostly to spend her first Christmas in memory alone.

Without alcohol.

* * *

At home in Simnasho, Chesley fought to keep the family together. Late one winter day, as he plowed snow from a remote logging road, he snapped a tire chain and his grader bogged down just as darkness fell. The cab was heated—he’d be warm there all night. But his grandchildren would be alone.

He lowered his 300-pound frame to the ground and started walking. He slipped and fell, but he soldiered on. He pushed himself along miles of icy, snow-packed roads in the dark to his pickup. He was in the wind-swept mountains, alone, far from help.

Just as he had been on Dec. 7, 1950, when after months as a combat medic in the Korean War, he was in one of the most brutal battles in U.S. military history when the Chinese swept over allied forces at the Chosin Reservoir. Chesley was shot through the leg and left behind. When Marines found him hours later, his blood had frozen his flesh to the ground.

He spent four months in the hospital, only to be wounded a second time when shrapnel tore through his truck in June 1951.

At home, Chesley’s grandfather was killed in a traffic accident. After he got back to the United States, Chesley applied for leave to visit Simnasho, but he was repeatedly denied. The first chance he got, he went anyway. He was arrested for being absent without leave and discharged dishonorably after four years of service, five Korean campaigns and the Purple Heart.

But Korea still surrounded him. He hung two U.S. flags on his living-room walls and covered them with photos of himself at the front. An ammunition belt hung from the ceiling. A dummy grenade sat on the top of the wide-screen television. Sometimes, in his road-grader, the whiff of diesel and grind of metal pulled him back to convoys of tanks and columns of soldiers marching through the snow. In his flashbacks, the soldiers were missing their foreheads, or their legs, below the knees.

As he did with his frostbitten feet in Korea, Chesley Yahtin put the pain out of his mind and kept walking. After the seven-mile trek from his road-grader, he finally climbed into his pickup and drove home.

The blue ranch house was a challenge for a man of Chesley’s age. Typically, he never knew who’d made it to school that day until he returned from work. Hip-hop pounded on the stereo. Teenagers padded across his chipped parquet floor and slipped downstairs to play video games. Friends came and went through a separate basement door so he never knew who was in the house.

Cecil Yahtin rested on his grandfather’s lap. “Eleven more days,” he said, until his mother graduated from her fourth attempt at drug and alcohol rehab.

He knew the kids were bright, but they hated school. Cecil was fighting, Dorothy’s daughter Chelsey was expelled for talking back, Sonny was skipping class and Cori, Chesley’s 18-year-old orphaned grandson whom he was also raising, had dropped out despite test scores that qualified him for talented-and-gifted programs.

The 90-minute one-way bus ride from Simnasho to classrooms in Madras was downhill for many reservation kids. By the time they were supposed to graduate from high school, most had dropped out. And it looked as though the Yahtin children would do no better. When the phone rang, it seemed as though it was either the school calling or the tribal police.

On Jan. 31, Warm Springs police found Sonny passed out in a car “too drunk to be a serious threat to anyone but himself,” according to the report. Chelsey was picked up for being in a car with alcohol. At one point she and Cecil stayed in Warm Springs with friends for nearly two weeks. When their grandfather called the police to report the kids as runaways, no one responded.

Sixty days after Dorothy entered rehab, Chesley, sick with the flu, drove to Portland alone. He settled into a chair next to Dorothy in a large gymnasium at the rehab center.

Indians circled a ceremonial drum. Graduates who’d completed the rehab program, relatives and counselors sat in a larger ring around them. Dorothy was ready to graduate.

Her youngest, Marcus, sat on her right, next to his father, Emil Johnson, who’d brought the boy from Warm Springs. The first-grader hadn’t seen his mother in three months. He’d forgotten what to call her. He climbed on her lap, kissed her face and called her “Dad.”

Relatives stood to give testimony. Chesley rose.

“My name is Chesley Yahtin Sr., father of Dorothy,” he said in a gravelly voice. “Myself, I am hoping she will do this finally. She has children she needs to take care of.”

“I am getting tired.”

* * *

After she finished rehab, Dorothy entered a transitional housing program that the Salvation Army provides for women. She moved into a shelter on Southwest Second Avenue and—through counselors—arranged for Cecil to join her. She was waiting on a sidewalk across from the shelter when Chesley drove up with the boy two weeks later.

Chesley popped his trunk to reveal Cecil’s clothes and a small television set.

Cecil’s grandfather moved the boy to Portland to join his mother, Dorothy, two weeks after she left rehab. But Cecil still didn’t trust his mother. When she was late returning from grocery shopping, he rode his bicycle to every bar in the neighborhood, peering fearfully through the glass.

“Thanks, Dad,” Dorothy said.

“That’s not for you,” Chesley grumped. “It’s for him.”

Dorothy smiled and hugged Cecil, who stood between them, silent. The skinny little 11-year-old hunched in a new plaid shirt buttoned to the neck under a pullover. He pulled from Dorothy’s embrace to look closely at her face, as if she were someone he recognized but was seeing for the first time.

Two days later, his mom walked him to a school bus stop. He wore a SpongeBob hat pulled low over a new buzz haircut and a large identification card pinned to his collar. He landed in Mr. Brand’s fifth-grade class at Chapman Elementary in Northwest Portland, with some of the wealthiest kids in town.

Dorothy took Cecil on the MAX train, to the zoo, to the top of the U.S. Bancorp Tower. She got him a library card. She smiled when he made snacks at the shelter and gave them away on the street. He gave his last dollar to a homeless man sitting in the rain.

An overwhelming new world lies ahead for Cecil after moving from Simnasho, population 85, to Portland. Dorothy took him up a skyscraper to show him the view of his new city.

Cecil worried about his mom’s money. How much she had. Where it was. When Dorothy was drinking, she spent or gave it all away. Cecil had learned to keep the family’s cash in his shoe. “You don’t have to worry about that anymore,” his mother said. “You don’t have to be a little man. I’m the little mom now.”

Dorothy joked a lot, but being sober was lousy. She tired easily. She felt brain-damaged. She couldn’t remember Cecil’s birth, his first words, his first-grade teacher. Her body lost its puffiness, revealing a puzzle of scars. She’d been hit on the head so many times by men she loved and women she thought were friends that she called herself “The Punching Bag.” She brushed her hair over the bald spots.

She was learning to live with the bad choices she’d made, and she’d made many.

Dorothy had never married. She’d had Sonny and Chelsey after brief relationships, and she’d met Cecil’s father, a Mexican immigrant, while drinking in Madras. He was a handsome carpenter, and they were together five years. They worked, but they partied, too, and one day, a friend brought cocaine. It was like flipping a switch for Dorothy. She snorted, smoked and—if someone had a needle—injected cocaine. She used it when she was pregnant with her fourth child.

The baby, Amelio, was born with what doctors described as “rotten fabric” for an esophagus and had to be rushed to Bend. Nobody knew what had caused the defect. But because the baby was born with cocaine in his blood, the tribes moved quickly, placing the newborn in a foster home for medically fragile children. Chesley drove Dorothy to tribal court to testify. Both agreed that Amelio needed to be with a foster family, a couple who could provide special medical care but who lived off the reservation.

Amelio would have more than 30 surgeries before he could breathe and swallow normally. But he survived and thrived, a miracle baby.

His mother became a pariah. She went to treatment and then to jail. Cecil and Amelio’s father vanished.

Dorothy met the father of her youngest child when she was working with him at a rock-crushing company the tribes owned. She and Emil Johnson started cashing their paychecks together. Soon they were expecting Marcus. Emil was a good provider; he kept a nice home and cars. But he was also a chronic drinker. He’d racked up six DUIIs and had been sentenced to a year in prison for drunken driving.

The couple drank when they were together and fought when they drank. He was jailed for assaulting Dorothy. Emil said she always provoked him. “Eventually, I’d lose my temper and wind up hitting her,” Emil said. “I’d finally explode.”

In Portland, Dorothy continued to make progress. In late March, she and Cecil moved out of the temporary shelter on Second Avenue and into the Salvation Army’s West Women’s & Children’s Shelter in Northwest Portland. Their belongings filled eight clothes hangers and two shelves. They played Candy Land, a children’s board game, and watched cartoons after school.

But at night, Cecil could hear his mother talking to her friends about wanting beer. She talked about beer all the time. She talked about her brother Randy, whose 1994 beating death remains the reservation’s most notorious unsolved murder. She said she envied his peace.

Cecil, curious, intelligent and sensitive, had a chance to live a different life in Portland with a sober mother and a safe home.

One day, when she hadn’t returned from an errand, Cecil jumped on his bike and rode through traffic, up and down sidewalks, looking into the open doors of bars, peering into the gloom to see if she was there.

But she was at the shelter, carrying in groceries.

Something was happening to Dorothy. She was going to parenting classes, counseling and Alcoholics Anonymous 12-step meetings. In late April, her behavior won her the right to rent an apartment on the second floor at the West Shelter, where she could stay as long as two years.

For the first time in his life, in the spring of 2003, Cecil’s mother was showing up. She was at school for Cecil’s class play. She was at the corner when he got off the bus. She was at Lloyd Center when he skated for the first time, waiting for him at the edge of the ice.

* * *

Spring unrolled in Warm Springs like a carpet, turning the cheat grass and bitterbrush a rich green.

Twelve-year-old Chelsey could see none of it from her cell at the Warm Springs Jail. The window was too high.

The tribes had almost no programs for runaways and low-level offenders. The only place authorities could put Chelsey was in jail, and she’d been there multiple times, once for 30 days in the past year.

She’d been arrested on the last weekend in May on her way to a dance. She’d been staying with friends off and on all spring, refusing to return to her grandfather’s. He’d reported her as a runaway.

Sonny Yahtin, 14, and Chelsey, 12, spent the last weekend in May locked up in the Warm Springs Jail. Sonny was jailed for violating probation on an earlier drinking and driving charge. Chelsey was arrested after being reported as a runaway. Their mother, Dorothy, had previously been held in the cell Chelsey was assigned. “Oh no,” she said, “the window in that room is too high for her to look out of.”

Her brother Sonny was already in jail, arrested a week earlier for violating his probation on drinking charges.

The two of them had a chance to get together in the jail’s courtyard, a tiny concrete space surrounded by 15-foot cinder-block walls topped with concertina wire. Overhead, they could see a brilliant blue patch of Central Oregon sky, but nothing else. They slouched on office chairs and talked.

Sonny said he’d stopped drinking five weeks earlier. “I want a better life,” he explained.

His black hair hung in his eyes. He hoped to get out of jail in another 11 days, on his 15th birthday. “When I get out of here,” he said, “I want to go see my mom. When I talk to her, I say, ‘What about me?’”

But the rules at Dorothy’s shelter didn’t allow boys older than 12. And Dorothy would be in the program for two more years. Sonny’s only option was back at his grandfather’s.

Sonny revered Chesley. He helped him fix cars and tied his hair back. But Sonny was traveling through adolescence like a car hitting black ice. “I don’t know what it will take to straighten that kid out,” his grandfather said.

In the jail courtyard, Chelsey curled up on her chair, tucking her bare feet under her. Her hair was pulled up in a loose bun and her 5-foot-6-inch frame was maturing rapidly. She looked 17, though the book she read in jail was the children’s favorite “Goosebumps.”

Friends and relatives agreed that the Yahtins had fallen apart when Dorothy’s mother, Amelia, died. Her death fueled Dorothy’s drinking. Dorothy’s sister Minnie left Brigham Young University just credits shy of graduation to take over at home. A decade later, Amelia’s absence was still profound. In the tribes’ oral tradition, grandmothers tell the stories, teach the Washat songs and protect children, especially girls.

Chelsey was a Simnasho girl without a grandmother. She was good at school, soccer, volleyball and making friends. But she hadn’t been a child for years. She could drive. She ironed her granddad’s shirts and cooked for her little brothers. She navigated a house full of boys who punched her and, as a practical joke, shaved her eyebrows one night as she slept.

A counselor told Chelsey that life is like school—you learn from those you’re with. Dorothy’s second-born learned from her mother and uncles. She didn’t think her mother would ever really quit drinking. And she didn’t see herself living beyond 30.

Still, she wanted to join her mother in Portland.

That possibility was growing. Dorothy had been sober for six months, and Cecil seemed to be thriving with her.

Two days later Chelsey appeared in tribal court for a hearing. Her grandfather joined her there and asked the judge to send his granddaughter to Portland to make a fresh start. Things looked positive at Dorothy’s. “Cecil,” he said, “has completely turned around.”

“Chelsey, what’s your attitude?” Judge Lola Sohappy asked. “Do you have anything to say?”

After months of sobriety, Dorothy returned home to face six outstanding warrants. “Roll out the red carpet,” she told a jailer over the phone, “I’m coming in.” But Dorothy feared that if she was found guilty, a conviction would destroy the progress she’d made.

“I just want to go home,” Chelsey whispered.

The judge ruled.

“Home” would be the West Women’s & Children’s Shelter with Dorothy.

* * *

Before Dorothy could bring her daughter to Portland, she had to face a year-old drunken-driving charge on the reservation. She called the jail in mid-June and said, “Roll out the red carpet. I’m comin’ in.”

The next morning she walked into the Warm Springs Jail and discovered not one warrant for her arrest, but six. All the fines she hadn’t paid and community service she hadn’t performed had piled up.

In a place where children are given names to live up to, the tribal grandmothers called Dorothy “Qwshiim—the disobedient or misbehaving one.” She still had the same reputation. “You can’t do anything right,” quipped a woman behind her as Dorothy stepped through the steel door into the jail.

Dorothy faced more than a year locked up and $3,000 in fines. She’d be completely derailed from her recovery program, and she might lose custody of her kids forever.

Suddenly, Dorothy admitted, she was afraid.

The jailer took her to the women’s cell, filled with her drinking buddies and memories of her old ugly self. She’d been jailed for drinking every year for the past nine.

As she sat in the women’s cell, she remembers thinking, for the first time, how she must have frightened her children. She got drunk in front of them and had shared beer with Sonny. She’d often black out and wake up to phone around and ask, “Do you know where my kids are?”

As she walked into the tribal courtroom in handcuffs to face the charges later that day, she felt the weight of what she’d done.

The lawyer appointed for her by the tribes asked that she be allowed to return to the program in Portland. “She’s making a lot more progress for herself than we’ve been able to,” he said.

“A lot of times it takes leaving the reservation,” said Judge Walter Langnese III.

Dorothy spoke: “My kids, I haven’t been there for them, and I want to be there for them. I want to be responsible. It’s not worth it to spend all my money on alcohol and drugs. My dad, he’s working all the time for us; he’s working now.”

“He shouldn’t be working and raising kids,” snapped the judge.

Then Langnese agreed to release her as long as she complied with the Portland program’s rules and resumed paying her fines out of her public-assistance payments.

Dorothy walked out into the sunshine and waved to passing cars. Some of them held friends headed out to drink and party. “Warm Springs will never change,” Dorothy said. “But Warm Springers can change—one at a time.”

* * *

Pi-Ume-Sha Treaty Days each June was the Warm Springs party of the year, part family reunion, part roundup. For weeks Dorothy looked forward to her chance for a triumphant return to the reservation. She was sober. And she had three of her children—Chelsey, Cecil and Marcus—living with her.

But Treaty Days was also the biggest temptation she’d faced since she began treatment. She’d be back around her old friends, with alcohol everywhere.

She bought a $10 yard-sale tent and planned to celebrate Marcus’ seventh birthday party at the parade grounds in downtown Warm Springs. She called her son Amelio’s guardians to invite them. Sandi and Al Thomas said they’d come.

In Portland, the children persuaded Dorothy to accept a ride to Warm Springs with her former boyfriend, Marcus’ father Emil Johnson. Dorothy grabbed the last campsite at the parade grounds.

But she quickly lost control of the kids, who ran off with friends. Her cronies weren’t around. And, given her reputation, the sober festival-goers eyed her warily.

Dorothy retreated into her old role with Emil, who took her shopping, cooked for her and moved their son’s birthday party to his house. Dorothy didn’t tell the guests about the change in plans.

Chesley has numerous scars and a Purple Heart for his service in Korea. He was honored with other Indian veterans at the Warm Springs’ Pi-Ume-Sha Treaty Days.

Amelio and his five foster brothers and sisters arrived as the temperature neared 100 degrees. Their foster mother, Sandi Thomas, dragged the group, one of them in a wheelchair, around the parade groups looking for the party. The children wilted. The Thomases gave up and left.

Chesley didn’t come either. All day, he’d been sitting in the parade-ground bleachers. Dorothy and his grandchildren streamed up, asking for money. He repeatedly opened his wallet and handed over $100 bills. And then, as he was about to be honored with other reservation military veterans, they all disappeared.

Chesley walked onto the grass. An announcer called families to stand behind their veterans to take part in a special tribal dance and song. Dozens of people streamed onto the field, arms around old shoulders, holding weathered hands. Chesley Yahtin, regal in his Chosin Few jacket and eagle feathers, stood alone. He looked around, saw no Yahtins, and his shoulders slumped. As the music began, he limped off the grass, alone.

After Marcus’ party, Dorothy fled to her tent, overwhelmed by her defeated expectations. At 3:30 a.m. she sat bolt upright—her daughter was missing. Dorothy leapt up and went outside just as Chelsey approached the tent.

All the frustration of the previous month boiled up. Being a mother was thankless, exhausting work. Cecil and Chelsey bickered constantly. Marcus demanded energy she didn’t have. The good feelings Dorothy expected once they were together never came. By the time Chelsey walked up, Dorothy was ready to erupt.

“What are you doing?” she said, “Were you drinking? Have you been getting high? I’m fighting to stay sober here. I’m fighting for us to have a chance. If you want to get drunk, let’s go get drunk. I’ll get it for you. Then we can go to my funeral because that’s where this is going.”

She sobbed.

Chelsey said nothing. She followed Dorothy into the tent.

Dorothy fell into a tearful, angry sleep and emerged the next morning dazed. That afternoon, an old friend approached her and asked for a ride.

Dorothy borrowed her dad’s car, packed it with five adults and two kids, peeled out of the parking lot and roared across the reservation boundary to the “wet” side of the Deschutes River. She pulled up to a campground store and gave her friend her purse so he could buy liquor.

Dorothy faced her greatest temptation when an old friend chugged Thunderbird fortified wine in her tent at the annual Pi-Ume-Sha celebration. “I wanted to drink with him,” she later said. “I wanted to drink with him so bad.”

They returned to the parade grounds. Inside her tent, Dorothy smiled and laughed nervously as her friend tipped back a bottle of Thunderbird fortified wine. They laughed. Dorothy could hear her children outside, playing happily.

She fiddled with her cell phone, but called no one. She played with a pack of Marlboro Lights, even though she didn’t smoke. She desperately wanted a drink.

The night before, she’d thought she could not go forward. On this day, she realized she could not go back. One drink, and she’d lose everything—her children, her father’s respect, her new life.

She would die.

She turned toward her pillow and cried and cried.

The next morning, she packed up and went back to Portland.

* * *

In some ways, Dorothy Yahtin still had a lot of growing up to do herself. Alcohol had frozen her development. Only when she completed rehab and began to heal did she begin to mature, and gain the discipline it took to be a parent.

Native American parents had traditionally been gentle with their children. Chesley Yahtin had never hit a child. Discipline was supposed to emerge naturally as kids grew up in extended families in isolated communities and unconsciously imitated the adults around them. But that system sometimes faltered in the modern world, where children took their cues not from adults but from friends, television and pop stars.

“I’d never been a real mom,” Dorothy said.

Her biggest challenge was learning to set limits for her children. When the kids begged, Dorothy spent more money than she could afford. When they pouted, she felt as inadequate as when her old math teacher rolled his eyes. She gave in.

She needed to learn, as every parent must, how to say “no.”

Dorothy cried at the edge of Shitike Creek the morning after she fought with her daughter, Chelsey, over alcohol. The fight turned violent, leaving Dorothy with a black eye, scratches and bite marks. “I want to be able to love her and hold her,” Dorothy said. “I didn’t do it then, but I want to do it now.”

On a Wednesday night in late July, when the kids begged to go to Simnasho, Dorothy agreed over the objections of her counselors. As soon as they arrived at Chesley’s house, her daughter Chelsey and her cousin disappeared. Dorothy found them 500 yards away in her abandoned house trailer. It was 3 a.m., and they had been drinking.

Dorothy argued with her daughter. The next morning she remembered the spat growing into a scuffle and then an all-out fight. Dorothy ended up with a black eye. Her arm had been bitten. In one horrible moment, there in the trailer, Dorothy saw herself and her brothers, drinking and fighting. She saw years ahead, she said, into Chelsey’s life. She saw her daughter’s grave.

No one else, she remembers realizing, was going to tell her children “no.” No one else would give them the patience, love and affection they needed. No one else could be their mother.

It was all up to her.

* * *

On a September morning six weeks later, Dorothy sat in Michelle Miller’s office at the West Women’s & Children’s Shelter in Portland. Every week since March, Dorothy had met with Miller, the shelter’s family case manager, for exhaustive rounds of counseling, scheduling and budgeting.

When Dorothy first arrived, she wasn’t even supposed to contact Chelsey. On this morning, the tribal court would decide whether Chelsey would stay with her mother for good.

Dorothy took the kids swimming in the Columbia River on a lazy summer day.

So much had changed. When Chelsey and Dorothy returned to Portland after the trailer episode, Dorothy wouldn’t let the girl go to the corner by herself. They went to family counseling. But they also went to the Columbia and Sandy rivers to swim. They went to arts camp.

Dorothy had lost weight, gotten a new haircut and new glasses. She was more patient with the children, too.

She took them back to Warm Springs to honor Chesley on the 50th anniversary of the Korean War armistice. Dorothy combed her father’s hair that morning “warrior style,” then she and her children danced behind him as he, wrapped in a Pendleton blanket, was honored at the longhouse.

Dorothy brushed her father’s hair “warrior style” and then danced behind him during a Warm Springs service honoring Korean War veterans. Her progress after alcohol rehabilitation was, Chesley Yahtin said, “the best thing that she has ever done.”

Chelsey celebrated her 13th birthday in Portland, surrounded by friends and family. As she blew out the candles, she no longer looked like a grown woman with adult worries. She was a cartoon-watching, gum-snapping, wisecracking teen.

“They are learning to be normal,” Dorothy told the Warm Springs judge in a telephone call. “It’s not normal to be violent; it’s not normal to be drinking and using drugs.”

The children had also learned to have a mother. Once school started, Dorothy walked them to the bus stop and helped them with their homework. She met their teachers, demanded they clean their rooms. She turned off the television and taught them card games. She told them, a thousand times, “NO!”

Dorothy was the first to admit that it would be at least a year before she’d be strong enough to move back to the reservation. But every day she saw progress.

Cecil worked on his art. He designed the logo for the Portland school district’s Project Return, a program for homeless children. It was a majestic eagle.

Chelsey, also an artist, sketched her long-term goal as well. It pictured her on a stage backed by rich blue curtains. An adult stood before a microphone, introducing her. She was wearing a graduation cap and gown.

“I know she’s better off here,” Dorothy said as the custody teleconference began. “My dad took good care of her, but he can’t do what a mother does.”

In her Warm Springs courtroom, Judge Lola Sohappy listened to Dorothy tell her story over the telephone.

Then she ruled that Chelsey be placed with her mother—permanently.

“No further contact with the court,” said the judge.

“This,” said Michelle Miller, sitting with Dorothy by the telephone speaker in Portland, “is miraculous.”

As she grew into her role as a mother, Dorothy Yahtin thought more about the future of her children, including Chelsey and Cecil. “I want them to go further than I did,” she said. “I want them to go to finish high school, to have a driver’s license, to go to college. I want them to have a better life.”

Dorothy and her children went home to Simnasho to visit. She remembered a dream that she was at the longhouse when two elders told her to fill baskets with the skills she’d need to care for herself and her children. Chesley had been performing Dorothy’s duties for years. And no member of the tribe could finally rest and pass on to the next life until someone else came along to take his place.

That weekend, Dorothy and Chelsey cleaned Chesley’s house. They swept his floors and did his dishes. They cooked for him. Then they went to see Chelsey’s best friend, a girl who lived in a remote home with an elderly grandmother. Dorothy and Chelsey did that woman’s dishes, too. They cleaned her house. Then they took Chelsey’s friend back to Simnasho to spend the evening with them.

At midnight, Dorothy sat dozing in her father’s chair. Around her, in the television glow, were the faces of her children, laughing and safe.

And behind his bedroom door, grandfather slept.