“Murat is a subtle writer and stylist, able to assimilate a wealth of archival evidence into a forceful narrative. She gives new poignancy to the problem of distinguishing between what patients say and how their doctors represent their voices, and she makes her own process in the archives part of the story she is telling. Her imagination, her curiosity, and her intellectual independence enable her to glean a new understanding of the mark of history on madness—showing, along the way, the pitfalls in too easy an understanding of mental life.”–Alice Kaplan, author of Dreaming in French

Buy this book: Man Who Thought He Was Napoleon

one Revolutionary Terror, or Losing Head and Mind

Here, as promised, is the exact truth of what happened. On getting down from the carriage for his execution, he was told that he had to remove his coat; he made some objection, saying that he could be executed just as he was. On being told that this was impossible, he himself helped to remove his coat. He made the same objections when it came to tying his hands, which he then held out himself once the person accompanying him said it was one last sacrifice. Then he asked if the drums would roll throughout; the answer was that they did not know. Which was the truth. He climbed onto the scaffold and sought to move to the front as though wishing to speak. But it was pointed out to him that this, too, was impossible. So he allowed himself to be led to the place where he was bound, and where he shouted very loudly, People, I die innocent. Then, turning toward us, he said: Gentlemen, I am innocent of every charge laid against me. I hope that my blood may seal the happiness of the French people. Those, citizen, were his true and final words.

This extraordinary account of the death of Louis XVI was written by Charles-Henri Sanson, his executioner. It was sent to the Thermomètre du Jour to refute the account of a journalist who claimed he was told by Sanson himself that the condemned man, showing cowardice in his final moments, tried three times to cry “I’m doomed!“ On the contrary, Sanson added, “And, to honor the truth, he bore all that with a calmness and steadfastness that amazed us. I remain most convinced that he drew this steadfastness from the principles of the religion in which no one seemed more imbued nor certain than he.“ This correction was corroborated by some of the reports of the day, such as a similar story published in Révolutions de Paris, which added details that Sanson’s sense of propriety censored. “At ten minutes past ten, his head was separated from his body, and then displayed to the people.“ The burial took place in the nearby cemetery of the church of La Madeleine. Witnesses who signed the official report declared that corpse had “no cravat, coat, or shoes“ but was “dressed in a shirt, a stitched vestlike jacket, gray broadcloth breeches, and a pair of gray silk stockings.“ The corpse “was seen to be whole in all its limbs, the head having been separated from the trunk.“ His head was placed between his legs in an open coffin that was lowered into the common grave and covered with quicklime and earth.

“A Usefull Invention of a Lethal Kind“

On that Monday, January 21, 1793, the last king of France died. Kings, as we know, were viewed as having two bodies. The mortal, secular body was twinned by a sacred body, the dynastic symbol of a monarchy of divine right. As Louis XIV had put it, “The nation is not a body in France, it resides entirely in the person of the king,“ an idea summed up by the more famous—if apocryphal—“L’état, c’est moi“ (I am the state). The king was an individual endowed with a function that transcended him yet was incarnated in a body considered inviolable and inalienable (a principle that was moreover accepted by France’s revolutionary constitution of 1791). An attack on the king was an attack on France, which is why regicides always deserved the worst torture (the 1757 dismemberment of Robert-François Damiens, who had attempted to assassinate Louis XV, was still on everyone’s mind).

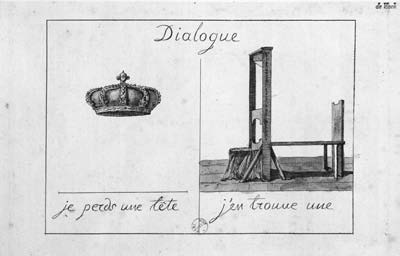

Yet this inviolable principle was delivered a lethal blow by the guillotine that severed the head of state along with the head of Louis XVI. The blade that fell on that day overstepped its usual role and flaunted its metaphorical powers. In an instantaneous image—a picture of gushing blood—it showed an age-old political regime tumbling into a wicker basket. Real body, symbolic body, one and the same: the guillotine hypostatized the king’s two bodies through this dismemberment on the public stage of the scaffold, putting a final end to tyranny. The crowd—which upon the death of a king usually shouted, “The king is dead! Long live the king!“—greeted the decapitation of Louis the Last with cries of “Long live the Republic! Long live the Nation!“ Some people dipped a handkerchief, the blade of a sword, or the tip of a bayo net in the royal blood, supposed to regenerate the nation and consecrate the birth of the Republic, henceforth confirmed by the literally staggering sight of a supernatural body suddenly split asunder.

Figure 3. German school, The Tragic End of Louis XVI, Executed on January 21, 1793, on Place Louis XV. This highly popular color print depicts a critical moment in the ritual of the guillotine: exhibiting the decapitated head to the public like a trophy. Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris. Photograph: Agence Bulloz. Photograph © rMn-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York.

The death of Louis XVI also confirmed and consecrated another obvious fact: the theater of political power, once restricted to Versailles, had shifted to Paris. The revolution was a drama being performed outdoors, in public. Right from the early days of 1789, François-René de Chateaubriand noted the effervescence of salons, cafés, and streets where everything became part of the spectacle of this “celebration of destruction.“ From 1792 onward, the scaffold became a leading stage. “The theater of the guillotine,“ added contemporary commentator Louis Sébastien Mercier, “was always ringed by an audience.“ The executioner Sanson was the great coordinator of these “red masses“ that drew daily crowds curious to see “the new play that could never have more than one performance,“ as Camille Desmoulins ferociously quipped only months before his own head fell. Artists took up their places at the foot of the scaffold to capture the expressions on faces faced with death, whose public staging offered the hope that skilled pencils might decipher its mystery. A plethora of engravings were published, endlessly showing the executioner brandishing a bloody head by the hair. Final words were noted down, poses were recorded.

Those sentenced to death, meanwhile, prepared to perform their final role. Imprisoned in Sainte-Pélagie, monarchist actress Louise Contat promised to sing a song of her own composing when she climbed the scaffold—a fate she was ultimately spared—which began with the lines, “On the scaffold shall I appear / for ’tis just another stage.“ The distance between street and stage vanished. Révolutions de Paris indicated as much in a strikingly metaphorical comment designed to suggest that life was returning to normal the very afternoon of that most exceptional January 21, 1793. “The show carried on without interruption; everyone joined in, people danced on the edge of the former Louis XVI Bridge.“

The guillotine became an everyday reality during the Terror. It was depicted, recounted, and bandied about by popular songs with their series of refrains on “the widow,“ “the national razor,“ “the patriotic haircut,“ “the sword of equality,“ and “the altar of the nation.“ People no longer referred to “being guillotined“ but spoke of “sticking your head through the cat-flap,“ “poking through the window,“ or “sneezing into the basket.“ Pro-republican women keen to flaunt their colors would wear earrings shaped like miniature guillotines from which hung pendants of a crowned head. Victor Hugo informs us that the artist Joseph Boze painted his teenage daughters “en guillotinées; that is to say with bare necks and red shifts.“ Once the Terror had ended, notorious “victims’ balls“ were held in Paris where relatives of the guillotined gathered in mourning dress, each wearing a red thread around the neck with hair pulled up or even shaved, the better to exorcise, in a cathartic danse macabre, the tragic escalation that the Thermidorian reaction finally brought to a halt.

In the meantime, the machine did its job rigorously, oblivious to propaganda, fantasies, and black humor. Figures vary depending on source, but it has been estimated that 2,600 to 3,000 people were guillotined in Paris between March 1793 and August 1794 (executions throughout the entire country during that same period totaled some 17,000). During the Terror, then, an average of five heads were lost in Paris every day—an average that should nevertheless be tempered by the fact, for example, that sixty-eight executions took place on July 7, 1794, just two days before Maximilien de Robespierre fell.

Figure 4. Guillotine earrings (ca. 1793). Gold and gilded metal, 5.7 cm. During the Terror, there was a spate of products such as these gold and gilt-metal earrings of a guillotine topped by the revolutionary Phrygian cap, with a dangling crowned head as a pendant. Musée Carnavalet, Paris. Photograph © Michel Toumazet/ Musée Carnavalet/Roger-Viollet/ The Image Works.

It is hardly surprising that the guillotine became what Dr. Georges Cabanis called “the standard“ of the Revolution, indeed was an emblem synonymous with the Terror. The Revolution severed the past, amputating diseased limbs from the body of the state, accomplishing an inevitable separation. The guillotine superbly exemplified and epitomized the vital need for rupture, which constituted the condition—and promise—for remaking the world. As a modern machine derived from the laws of geometry and gravity, it promised an egalitarian, democratic death. It put a permanent end to the hierarchy of punishments under the ancien régime, which sentenced witches and arsonists to be burned at the stake, regicides to be tortured, and thieves and criminals to be hanged, reserving decapitation by the sword for the nobility. It was to do away with this inequality—even in death— that on October 9, 1789, Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, an elected representative to the Constituent Assembly, suggested a new form of capital punishment that would be identical for all. Article 6 of the statute adopted on December 1 read, “Criminals will be decapitated, through the action of a simple mechanism.“ But three years passed before the decision was implemented. The revolutionaries spent less time in 1789 debating the potential abolition of the death penalty—an abolition stoutly defended by Robespierre—than on discussing the modalities and implementation of the dreadful machine, which saw the light only in 1792.

Figure 5. Poirier de Dunckerque, Cutting Manners [Les formes acerbes] (1796), 34 cm × 38 cm. This print shows Joseph Le Bon, who sent hundreds of suspects in the region of Arras to the guillotine. The picture provides a powerful synthesis of the horror provoked by decapitation, the mutilation of bodies, and the bloodthirsty “Terrorists.“ Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris. Photograph: Agence Bulloz. Photograph © rMn-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York.

France did not invent this method of execution, but it altered the scale of operations, bringing death into the era of technical mass production. Other beheading devices had proved their worth in the past, such as the Diele in medieval Germany, the mannaia in sixteenth-century Italy, the “maiden“ in Scotland, and the “Halifax gibbet“ in England. The French guillotine was nevertheless more efficient than its predecessors, thanks to the development of a swivel board on which the condemned person was bound, the design of a lunette (double-sided yoke) that held the head steady, and finally the use of a diagonal rather than a crescent-shaped blade, which meant that the instrument “never failed,“ according to a report submitted on March 7, 1792, by Antoine Louis, its true inventor. Indeed, the machine was briefly nicknamed the Petite Louison or Louisette. Louis, like Guillotin, was a doctor. In fact, he was a famous surgeon who served as the permanent secretary of the Académie de Chirurgie, making him the ideal person to accurately assess the conditions required for a swift, flawless severing of the head.

Figure 6. French school, Dialogue: I’ve Lost a Head [says the crown]; I’ve Found One [replies the guillotine] (1793). Colored etching, 11.2 cm × 16.2 cm. The guillotine introduced impersonal, assembly-line executions. Even the king was reduced to just one head among many in this chilling “dialogue“ of 1793. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Photograph © bnF.

Once Louis’s report was accepted, the machine could be built. The joiner at the royal household having submitted an estimate judged too steep (5,660 livres), the choice fell on a Prussian piano maker, Tobias Schmidt, whose bid was far more reasonable (960 livres). But the Ministry of the Interior refused to grant Schmidt the patent he had requested. “It is humanly distasteful to grant a patent for an invention of this kind; we have not yet reached such a level of barbarity. While Monsieur Schmidt has produced a useful invention of a lethal kind, since it can be used only for carrying out legal sentences he must offer it to the government.“ There was a double meaning being expressed here: while the government was not adopting the guillotine with a joyful heart, it truly intended to make it a “machine of government“ (as writings of the day refer to it, in fact). So it was a political machine designed to implement a death alleged to be painless and also impersonal, because a pulley, a diagonal blade, and two uprights—the product of talented French engineering—would replace the hands of the accredited executioner.

The first successful trials—on live sheep and three human corpses— took place in Bicêtre, just outside Paris, early in the morning of April 17, 1792. They were done in the presence of doctors once again, including the famous Dr. Cabanis. Decidedly, the medical corps attended upon the guillotine. Nor was that all. In the fall of 1795—once press censorship had been lifted—Le Moniteur Universel published a letter from Dr. Samuel Thomas von Sömmering, an anatomist who had written his thesis on the arrangement of cranial nerves, which sparked a polemic over the potential survival of consciousness after decapitation. Based, among other things, on experiments by Luigi Galvani and the persistence of feelings of amputated limbs, this German doctor reported testimony of heads that gnashed their teeth after beheading. He remained convinced that “if air still regularly circulated in the organs of the voice, had they not been destroyed, these heads would speak.“ Sömmering felt that the allegedly humanitarian guillotine was barbaric and a much poorer option than hanging, which led to death “via sleep.“

That is all it took for a debate to flare up. The Franco-Prussian journalist Conrad Engelbert Ölsner—to whom Sömmering addressed his letter—went to bat in the Magasin Encyclopédique, followed in that same publication by Jean-Joseph Sue (father of novelist Eugène Sue). Ölsner then went on to publish his notes in a small book on the question. The French notably referred to the death of Charlotte Corday, beheaded on July 17, 1793, whose cheeks purportedly reddened in indignation when her head was pulled from the basket and slapped by a revolutionary. Was this incident rumor, collective hallucination, or a conspiracy by enemies of Jean-Paul Marat? The posthumous outrage reportedly displayed by the “angel of murder“—as Alphonse de Lamartine dubbed Corday—fueled discussion in the press when Cabanis who, like Guillotin, was a member of the Ideologues group at the Nine Sisters Masonic lodge, decided to respond by publishing a Note sur le supplice de la guillotine (A note on execution by guillotine), which temporarily put an end to the dispute. Cabanis, who would later write a famous book on the relationship between human physical and mental faculties (Rapports du physique et du moral de l’homme [1802]), insisted that movement and feeling be dissociated: a headless chicken may continue to run around but feels nothing. A human being whose head has been severed through the spinal cord no longer has nerve sensations and can therefore in no case suffer. Corday’s blush was to be dismissed as an absurdity. Potential movements of the face or body—convulsive or regular—“prove neither pain nor feeling; they result solely from the remnants of a vitality that the death of the individual, the destruction of the self, does not instantaneously extinguish in muscles and nerves.“

The guillotine thus served as the focus of highly lively and crucial debate on the mental, political, and metaphysical assessment of the individual: an individual, literally, is one who cannot be divided. Medicine, sister field of philosophy, not only took part by involving itself in the birth of the guillotine from conception to implementation, but appeared from one end of the process to the other as the instrumental, organizational, and rhetorical domain that acted as arbiter of life and death. Right from the start, medicine laid down the terms of debate: What is torture? What do convicts deserve? Should death be painless? Does consciousness outlive the flesh? What is a divided “self “? This, indeed, is the very site of the origin of the medical approach to madness: the invention of psychiatry.

Figure 7 . French school, The Execution of Marie Antoinette (between 1793 and 1799). Etching, 13.5 cm × 8.5 cm. This engraving, though archived under the title The Execution of Marie-Antoinette, has also been alleged to show the death of Charlotte Corday, whose cheek was seen to “redden in indignation“ when her head was pulled from the basket and slapped by the executioner’s assistant. This incident, apparently depicted here in the cloud, fueled debate over the survival of consciousness after beheading. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Photograph © bnF.

Copyright notice: Excerpted from The Man Who Thought He Was Napoleon: Toward a Political History of Madness by Laure Murat, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2015 by University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)