“Remarkably original. No Way Out is deeply infused with knowledge of the ethnographic literature that has identified today’s still acute policy issues in poor, urban, mostly black—and often crime-ridden—communities. To read this book is to be assaulted by the realities of Bristol Hill—and other places like it—and to become aware of the fine lines binding the heroic to the tragic in the lives of its people. No Way Out does what few other books of its kind do. It makes multiple contributions to the scholarship, while telling the stories of Bristol Hill in a way that is plain for anyone to understand.”–Charles Lemert, senior fellow, Urban Ethnography Project, Yale University

Buy this book: No Way Out

Dealing on the Street

The neighborhood is one place by day and another at night. On weekdays at 5:00 p.m., everything seems to change. There is more traffic, the noise level rises, and more people are out walking. Outsiders and patrol officers leave; so do missionaries and social workers. Residents who work outside the neighborhood during the day return home. After one set of outsiders is gone, another set appears: a steady stream of customers drives into the neighborhood between the end of the normal workday and midnight. To get a sense of the flow of daily life, I observed Lyford Street at different times of the day and from different places. I watched the dealers’ regular shift changes and saw them being resupplied with drugs. I also observed residents leaving and returning home to see how they managed proximity to dealers, monitored the influx and exit of visitors, and noticed how time changed the social order of places and situations.

Lyford Street is located just off a major expressway, with an entrance to the highway at one end of the street and an exit from the highway at the other, giving buyers from the wealthy suburbs surrounding Bristol Hill easy access and egress. The drug corners in the neighborhood are located in such a way that purchasers can get off the expressway, buy their drugs while remaining in their cars, and then return to the expressway quickly.

The location would not matter so much if the customers lived in or near the neighborhood, but they are almost all from out of town and almost all white. These buyers are rarely caught. Law enforcement efforts concentrate on the dealers, even though without customers there would be no dealers. A police officer who patrols Lyford Street told me that earlier efforts to focus on the buyers were halted following complaints that they involved racial profiling of white visitors to this black neighborhood. Dealers could be seen flagging down any cars that drove by slowly or had white occupants. The lighting on these streets comes mostly from houses and car headlights because the dealers shoot out the streetlights or hire “maintenance” men to dismantle them. Nonetheless, white customers are very noticeable. The double stops required are a familiar feature of the routine. The first stop is to place an order and pay; the second stop is to pick up the drugs.

The strategy of having a team of three working each deal, only one of whom touches the drugs, and then only for a few seconds, makes it very difficult for the police to make significant arrests. While drug dealing is illegal, it is nonetheless closely tied to the overall economy. For instance, competition between dealers increased during the economic downturn in the fall of 2008, and I witnessed dealers chasing after cars trying to get their business. The shared understanding that the dealers all live on Lyford Street meant that dealers who worked the block tolerated competition only from neighboring dealers. Nevertheless, competition among them could become quite fierce.

Identifying Features of Drug- Dealing Areas

Several visible features identify this neighborhood as a place for drug dealing: graffiti, vacant lots, gym shoes hanging suspended from electrical wires at corners, broken streetlamps, and strategically placed small piles of trash.

Graffiti expresses broadly shared community sentiment. The most elaborate are murals memorializing drug dealers, innocent bystanders, and valued members of the community who died as a consequence of the drug trade. They symbolize both community solidarity and the sacrifices that some members of the community are seen as making for others in a high-risk game. Vacant lots are often created through the concerted efforts of upstanding citizens who hoped to curb the spread of drug dealing by having the city tear down vacant houses. Thus, vacant lots are evidence of residents’ collective efficacy, not of neglect. The gym shoes hanging from electrical wires are placed there by dealers to mark the boundaries of drug-dealing areas, and buyers look for them. Even trash plays an important role by providing places to hide drugs and guns; if it is removed, the trash pile will be replenished.

Although the police contend that the community would be better off if the city enforced property codes and removed graffiti, the benefits are debatable. Most houses and yards are kept up fairly well, and neighbors help with cutting grass and cleaning trash when they perceive that someone has a problem maintaining their yard. The worst residential properties are those with high tenant turnover and absentee landlords who do nothing to keep up the property. Fining landlords might work, but fines would be beyond the means of the tenants. Most of the unkempt properties, however, are vacant houses and lots owned by the city and state. The memorial murals, a sacred type of graffiti, are a special case. Removing them would be offensive. They are a valued representation of community sentiment toward a deceased person whom residents perceive as wrongfully killed and who is still mourned by those who live nearby.

Indeed, these murals and memorials on Lyford are one of the more noticeable results of solidarity and collective action in this community. These memorials, which are created at the site where death occurred, are of two types. The first are murals for drug dealers. These tend to be large, elaborate, and relatively permanent; the oldest on Lyford Street commemorates a death in 2003. Not every drug dealer who is killed earns a mural. They indicate a measure of respect for the deceased and a recognition that his death was a sacrifice for a drug trade that is created and sustained by locals. During Jonathan’s trial, when a prosecutor asked a youth from the neighborhood whether a specific mural honored a particular drug dealer, he answered, “No one would ever paint a mural for that person” and laughed derisively. Jonathan told me forcefully that “assholes don’t get murals.”

The five murals in the neighborhood span areas up to twelve by eight feet and are painted on the sides of houses, often near drug-dealing locations, as a reminder of both the dangers dealers face and the honored members of the community with whom they share these risks. Like a grave headstone, the murals often give the deceased’s dates of birth and death accompanied by “RIP.” Other messages include “in memory of,” “we love you,” “real niggas hold you down,” and “we miss you.” The murals are colorful and well done. The artists often signed and dated them on Lyford Street. These murals illustrate a sense of solidarity as well. The “real niggas” are those who truly know you; in doing so, they support you as well. These memorials carry significant meaning for community members, and when outsiders treat them as anything less than sacred objects they are actively denying that deep meaning and the role they play in community life—ironically, further increasing the solidarity of insiders.

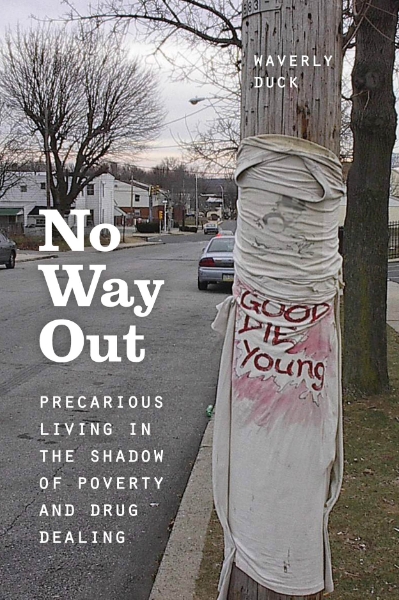

The memorials for “innocent” bystanders are very different from those for drug dealers. Temporary collections of cards, teddy bears, and candles around telephone poles and lampposts memorialize bystanders and other valued members of the community who were killed by the violence associated with drug dealing. As with the drug dealers, not every victim gets a memorial; they are memorialized if a sufficient number of people view their death as unfortunate, undeserved, or sacrificial. I saw only two bystander memorials during a period when at least four other people were killed by drug-related violence. The vigils held at the memorials are large gatherings that both evoke and symbolize ritual solidarity. Many people attend over a period of several days. That the local drug dealers themselves are not seen as the cause of these deaths is evidenced by their presence at memorial vigils and their positive interactions with other residents there. It is my impression that drug dealers sponsor some of these memorials. People in the neighborhood feel that loss and danger are something everybody is subjected to and nobody has any control over; the fault lies outside the community in the unfair circumstances they are all forced to share, not in the actions of a few community members.

Corner Boys

All of the dealers who sell drugs in Bristol Hill are known as corner boys, although they also work from vacant lots along the street. The corners are the most prominent drug-dealing spots. Dealers need to be easily visible to buyers driving in from the expressway and yet be able to disappear quickly if the police show up (Manning 1977, 1980, 2008). Although dealers are available around the clock, most action occurs between six in the evening and midnight.

On a single shift, two or three dealers work a spot together. The first is an order taker and money collector. He identifies the buyer, takes a drug order and cash, and communicates the order and pickup location to a second member of the team. That person retrieves the drugs, which are usually stashed in small amounts throughout the block under bits of trash or rocks. He takes out only the amount of drugs required for that purchase and delivers it directly to the customer. The order taker and drug deliverer are usually in close-enough proximity to see each other, and typically the order taker sends the customer’s car toward the drug deliverer. If surveillance becomes a problem, then the process becomes more complicated. For instance, the buyer could be directed to a more obscure pickup spot or be told to show up somewhere else at a specified time. The third person, a lookout, circles constantly, watching for police and customers. It is more difficult to identify this third person, but informants told me that they are almost always there on Lyford Street. Certain children and teenagers walk around the neighborhood for the dealers, keeping an eye out for customers and law enforcement.

Although dealers usually dress extremely well and in the latest fashion when they are not dealing drugs, they wear something like a uniform while they are working. In the summer they dress alike in white T-shirts and tank tops and dark pants or shorts. In the winter they wear black Dickies or carpenter pants and black hooded sweatshirts. While these outfits mark them as drug dealers, they also make it very difficult for the police to distinguish dealers from one another; from a distance, they all look alike. In a chase, for instance, the police might start out after one dealer and end up catching someone else. Dealers choose locations with many escape routes and poor lighting so they have an advantage. Since only one of the three team members is ever holding drugs, they can switch places and prevent the police from catching them with anything (Manning 1980).

I was sometimes able to observe top dealers who supplied all the corner boys. They usually remained mobile, circling the block during the day and resupplying drugs when dealers ran low. They did not carry the drugs with them but directed dealers to locations where drugs were hidden. Most of the drugs were stored in vacant houses, under cars, and in bags that resembled trash. Not having drugs in their houses or cars or on their persons protected them from stickups as well as arrests.

Since the quantities at each location were small, if a dealer was caught, the loss would be limited; so too, at least theoretically, would be the punishment. Guns were considered an important tool, but the penalty for being caught with a gun made it too dangerous to carry one while working. Dealers handled the guns the same way they did the drugs. Most shared guns that were hidden close by but never kept them on their person. The practice of storing drugs and guns in public places where the kids in the neighborhood could see them bound the kids to the dealers’ code. Protecting these public spaces from predatory outsiders was essential.

The Youngest Dealers on the Day Shift

Although the morning hours between eight and ten were the slowest in terms of drug dealing, I enjoyed watching kids go off to school and adults leave for work and witnessing the arrival of other people who worked in the neighborhood, such as trash collectors, city maintenance staff, electricians, and social workers. This was my favorite time of day because the morning drug dealers tended to be the youngest and the least threatening. They didn’t bother me, and I didn’t bother them. According to Dave, morning is the worst time to be out selling drugs; there are fewer drug buyers, no cover, and no younger helpers. This shift is left to the youngest dealers.

When dealers took breaks, the corner was unoccupied for ten or fifteen minutes, and I could take field notes and photograph the spots where they worked. I tried to walk around the neighborhood in such a way that I could make observations without being noticed by the dealers. I was especially careful not to do anything that would draw the attention of the more powerful dealers and suppliers. Most of my photographs were taken during the day, when drug sales were infrequent. On some streets I slowed my pace; on others I hurried. In accord with the code of the street, I never made direct eye contact with dealers, even when they were being helpful, and on the few occasions when we did cross paths I spoke only if spoken to. Whether out of ritual or curiosity, the older dealers would sometimes greet me and I would then return their greetings.

The dealers working the afternoon shift are a little older and more trusted by the suppliers and adult dealers. School-age children are around in large numbers to run errands and serve as lookouts. The pace of selling drugs picks up, but because it is still daylight, the dealers work in full view. The risk of arrest is higher than at other times. Older dealers who work this shift might do so in the role of order taker, without coming into contact with drugs at any time. The children play an important protective role here, and they are available to hold drugs for older dealers being chased by the police.

Old Heads on the Night Shift

The old heads, those who have proven themselves as dealers, are no longer juveniles; if caught, they serve time. They are also more likely to have prior records and draw longer sentences if arrested and convicted. Working after dark gives them some cover from the police. Since they are making more money, they are much more likely to become the targets of stickups. The risks increase enormously for dealers as they progress up the career ladder.

At the same time, more experienced dealers take more precautions. I was unable to make extended observations at night because it was too dangerous. From the observations I did make, I could see the same teamwork that characterized the daytime shifts. But most of my information about the older dealers comes from informants.

Groups of old heads were known to seize drugs and money from other dealers by brute force. At times, I was told, they would accost their chosen victim and torture him until he revealed where his major stash was located. Since the location of the stash was secret and yet in a public place away from their own location, it was never guarded.

The proliferation of guns on the street is due in part to the extreme danger of dealing. Guns are used to protect a dealer’s drug supply from stickups and addicts—not necessarily their own clients. Dealers also rely on guns in an effort to keep their families safe. They may use guns to collect payments from customers buying on credit or to punish an addict or rival dealer who steals drugs from a stash spot. Pistol-whipping addicts and customers for stealing or for failing to pay is a common practice. A drug dealer who does not protect his “face”—that is, his honor and reputation on the street— will not last long. Buying and exchanging guns is relatively easy for anyone. Because the guns are not kept on dealers’ persons, anyone wanting to use one must first test it to see if it is loaded and will fire. Firing guns in the air to make sure they work and to elicit fear accounts for most of the frequent gunshots heard in this neighborhood.

Vacant Lots and Playgrounds

In the neighborhood around Lyford Street, public space and open space are treated quite differently. Despite a widespread belief that drug dealing occurred in public parks, making them unsafe, I never observed drug dealing in any public space. Several informants confirmed this fact. Indeed, public spaces were poor locations for drug dealing. Drug dealing occurs in open spaces with easy access and egress, while public space is usually fenced in and centrally located. Residents seem to avoid official public spaces, while nevertheless doing their business in public. Spaces designated for public use in this neighborhood are, in any case, extremely limited. The last remaining playground in the neighborhood was demolished in 2008.

I heard two different accounts from officials about why the playground was demolished. Their explanations suggest not only the stereotypes that outsiders impose on Lyford Street but also how the bureaucracy rationalizes its own unjustifiable actions. Initially, the police alleged that the playground was dangerous for children and an eyesore. A city employee who did not live in the community claimed that the park was unfit for children to play in. He put it on a demolition list, and less than a week later it was gone. When asked why he had the park torn down, he said it was not because of the play structure, which was safe, but because of the “negative element” that he claimed hung out there. When pressed, he asserted that the park had become a “haven for drugs, murderers, and dead bodies.” No violence had ever occurred in the playground, however. Ironically, most of the murders and drug deals that occurred in this neighborhood took place near vacant lots like the one that had just been created. After the playground’s demolition, the city produced a report stating that it was condemned for safety reasons such as bad lighting.

The park was hardly a suitable spot for drug dealing. It was surrounded on three sides by a high fence, behind which stood houses with their backs to the playground. The fourth side faced a street that was separated from the highway by a service road. There was only one gate through the fencing. To reach the playground, a car coming from the highway would have had to drive deep into a dark and uninhabited part of the neighborhood, which would not appeal to white suburbanites. Unfortunately, the park was equally badly situated for use by children. Parents were reluctant to allow their children to play there, even though the playground was well equipped, because they could not see them from their front windows or access it through their yards. The playground was always deserted, although once I saw a few adults sitting and talking there in the dark. Three weeks after the demolition of the park, the city received a grant to build a new playground, but it was not located in this neighborhood.

The rationale of deterring crime was also used as a justification for removing the bus shelters from this neighborhood, which was done just before the playground was demolished. Observing this process provided some insight into how other public spaces in Bristol Hill had been dismantled over time. The irony is that this systematic effort to eliminate public spaces to prevent interaction with drug dealers forced people to interact on the street—where the dealers are active. The practice of dismantling and demolishing public spaces has created many vacant lots, which are overgrown with grass and deliberately strewn with trash. Residents, very few of whom own cars, must routinely walk by vacant lots where guns and drugs are hidden.

How Interaction Orders Shape Individuals’ Choices

While participants in orderly social settings can exercise some choice over the actions they perform, the social situation and the expectations it generates frame their choices. What they do and do not do is interpreted by others in predetermined ways, regardless of their personal motivations or intentions. Equally important, social settings are organized around commonly understood practices that constrain the alternatives open to participants. The interaction order leaves most people with very little choice over the set of practices they engage in. Although those who occupy privileged positions often operate under the delusion that they have the power to decide their own course, few black people who live in poverty can maintain this illusion.

The code of the street is buttressed by a set of background expectations (Garfinkel 1967) through which residents organize social interaction in their neighborhood. Unless we comprehend the compulsions of this local interaction order, we cannot understand what happens to children who grow up there. Analyzing actions that take place in neighborhoods like Lyford Street without context and according to external standards is a fundamental error. Everyone who lives in the neighborhood must become oriented to the situated practices through which the code of the street is implemented, whether they like it or not. Under such conditions, the idea that a child chooses to become involved in criminal activities is wide of the mark. Unless the entire matter of drug-dealing careers is approached differently, the desperate conditions that exist in places like Lyford Street will continue to produce an endless supply of young black men to fill our prisons.

The local order on Lyford Street both constructs and enables the choices and resources that are available to people. The specific location in which people find themselves can profoundly shape their personal feelings and attitudes. Focusing on how the locally situated character of the social order that composes daily life frames the choices and resources available to people is an important corrective to the preconception that individuals choose their situations or that their attitudes and values shape those situations. This tight framing of the possibilities for daily interaction leads to another characteristic of Lyford Street and neighborhoods like it: a profound contradiction between the beliefs residents hold and the practices they engage in. Because practices rather than beliefs drive the orderliness of social action, there is always some discrepancy between the norms and actions (Anderson 2002; Rawls 2000, 2009). On Lyford Street, this contradiction took an extreme form. Because the practices that so closely circumscribe daily interaction support an illegal activity that conflicts with residents’ deeply held values, they have no opportunity to act on their values. This fundamental contradiction between beliefs and behavior does not reflect on the moral character of individuals.

The social order of such neighborhoods rests on the nature of the underground or illegal economic enterprise and the orderly practices necessary to succeed in it, not on what people believe, value, or want for themselves and others. Communities where drug dealing structures the economy have different local order practices than communities where sex work or working off the books are the main illegal enterprises. Understanding how individuals enter these careers requires comprehension of the specific local order that structures the choices available to them (Adler 1983, 1993; Murphy, Waldorf, and Reinarman 1990). Assuming that they have the same choices as middle-class people living in the suburbs is naive. Even assuming that the local order of all neighborhoods where drug dealing flourishes is the same is problematic; the relationship between residents and dealers in small cities like Bristol Hill is significantly different from that in large cities like Chicago.

Money and Guns

In Lyford Street, independent dealers are ranked in a hierarchy based on age and experience. The convergence of multiple actors and the layout of the neighborhood explain why dealers themselves seldom hold drugs or drug money. Several trade practices were apparently designed to limit the potential for lost money and drugs, police raids, arrests, and criminal charges. These include the use of guns, which are stashed near the dealer’s corner but, to avoid felony firearms charges, are rarely carried; the constant resupplying of drugs to dealers; the limited amounts of cash carried by dealers; and the division of labor between lookouts and corner boys. According to numerous informants, these ways of controlling losses and arrests developed in response to the legal and informal risks associated with the trade, especially police raids, armed robberies, and sanctions from suppliers who provide drugs on credit. Significantly, the same practices that protect dealers from the police also shield them from being robbed by other criminals, ensuring that, when things go wrong, drug money can easily be repaid and sales are only temporarily disrupted.

Dealers must take into account the risks associated with working in an illegal economy, such as stickups by groups in search of cash and drugs (Contreras 2012). The old heads who supply drugs are highly mobile. Those who are successful are likely to move out of the neighborhood. To avoid being found, they live in properties rented in the names of others, such as parents, girlfriends, relatives, and friends. They can earn about $1,000 to $1,200 a week by selling approximately 2.5 ounces of powder. Some old heads are major suppliers and live in port cities along the East Coast. The corner boys are much more vulnerable to robbery, as well as arrest. These factors limit the amount of money they make.

Gus, a former dealer who had attended Sunday school with Jonathan, described the cash exchange and moneymaking practices on Lyford Street. “If my old head was to give me something like a ballgame [3.5 grams of cocaine], you could bag up $200. He would just want $100 off of it or $125, and I would get the rest. Or he might just want $100 and I get $100, so we were both making something off of it.” This account is very telling, not only about the large profits to be made on the corner but also about the hierarchy, the potential for credit, and the ability of dealers to negotiate rates of return.

When Jonathan started to become successful at dealing, he became a target for stickups. Stickups are dreaded because when drugs are given on credit, the dealer must pay the supplier even if the drugs or proceeds have been stolen. Most dealers fear stickups as much as they do arrest. The old heads would even target younger dealers as a way of making easy money. To enrich themselves, corner boys have been known to claim that their drugs were stolen while withholding the money from their suppliers. What I witnessed on the corner suggests that this tactic is rarely successful: drugs supplied on credit must be paid for, regardless of raids or robberies.

Jonathan was held up after a man he had known most of his life, a prominent old head who worked as a bus driver at night and sold cocaine on the side, took him to a house in an expensive neighborhood that he pretended was his. Standing at the door of the house without going in, the man appeared to take Jonathan under his wing, explaining the rules of the drug game and how to turn a major profit, assuring Jonathan that he too could have such a house. While the old head was winning Jonathan’s trust, Jonathan volunteered information such as how much “weight” he was moving, where he kept his stash, and how much money he made in a month. Jonathan later discovered that the man had set him up to be robbed. When he was tipped off by an older dealer, he remembered the encounter and the information he willingly volunteered. After the robbery, Jonathan became more covert and less trusting of those around him.

Drug Careers Rarely End Well

The experiences of youths like Jonathan reveal an interaction order of drug dealing on Lyford Street that sweeps up most boys and young men who live there. The sense they learn to make of daily life in this space, which is necessary to navigate the street safely, inexorably draws them into drug dealing.

The rule of law is not only at odds with the code of the street but frequently, although unpredictably, disrupts the order that normally exists there. Dealers must routinely manage a terrain filled with complex situations that blur the line with regard to the rule of law, the work requirements of drug dealing, and the expectations of those who live in the neighborhood. Unfortunately, the criminal justice system does not recognize the social order that exists in places like Lyford Street as a force that shapes young men’s options or take it into account as a mitigating factor when they are charged with drug offenses. These ordered practices are by definition illegal, and once brought under the gaze of law enforcement agencies, they are sanctioned as though the participants had the same choices available to middle-class youths.

The situated contexts and interactional moves involved in selling drugs on Lyford Street compose the order of this neighborhood. The social identities that are possible to construct in this community are severely constrained by the lack of job opportunities produced by long-term economic decline and compounded by arrest records that are nearly universal. The violence that erupts periodically entails incalculable risks, but does not weigh as heavily on young men as their chronic economic exclusion. Managing and performing social identity is always a situation-specific process, however, and knowing what the available identities are does not explain how and why people adopt them.

Most seriously, the social order that exists on Lyford Street cannot be counted on. A level of unpredictability remains, creating a situation in which nothing can ever be taken for granted. As Harold Garfinkel (1967) argued, being able to take social orders for granted is one of the foundations of understanding, trust, and stability in social life. When nothing can be assumed, social life has a fragile edge that makes it very different from more conventional social arrangements.

The street’s social activity is highly predictable between incidents, but drug-related crime and the incursions of law enforcement make it impossible to know how things will transpire from one moment to the next, much less over the long term. Consequently, people in the neighborhood maintain a constant vigilance and laser-like focus on the present. The need to gauge the uncertainties surrounding a drug deal gone sour, a robbery, or even a murder, all of which carry the equally unpredictable risk of police involvement and arrest, constitutes the local interaction order. Over time, tactics geared toward immediate survival become paramount, limiting planning for the future and precluding extended consideration of the potential consequences of present behavior.

Fundamentally, in consonance with the exigencies of the local interaction order, the near-total lack of access to mainstream economic and societal resources in neighborhoods like this places most people in situations with little autonomy and control over their everyday lives. Having a job and living one street away from a drug-dealing corner does not insulate anyone sufficiently or exempt them from the necessity of understanding and negotiating the interaction order. Employment or homeownership may make certain aspects of living more predictable, but the infrastructure supporting much of daily life in the neighborhood remains uncertain. People must enter and exit the neighborhood. Their children must go to school and play with other children. Their homes are within reach of bullets from drug dealers’ guns. Proximity to the underground economy of drug dealing and the social systems that support it makes it very difficult for anyone to escape.

The embedded local order of the drug scene shaped Jonathan’s entry into drug dealing. His life history offers a vantage point from which to understand the community as a whole. The organization of the neighborhood, its position in the economy, the location of access and escape routes, and the intricate familial and friendship networks produce a social environment that facilitates the recruitment and training of dealers. Induction into drug dealing involves learning many valuable skills that would contribute to these men’s success in legal occupations if any were available. A successful career in the drug trade requires mastering multiple tasks and calculating risks and benefits in an environment that, despite its ordinary orderliness, remains unpredictable (Laub and Allen 2000).

Comprehending these local social forces offers a valuable perspective on Jonathan’s involvement in the drug trade and its effects on his life and that of his family. Jonathan is not merely a victim of circumstances, but many of his actions and choices are intelligent and rational given his circumstances. Community members’ lenient attitude toward drug dealing is influenced by their understanding of young men’s marginal position relative to the mainstream economy. In other words, although boys’ involvement may stem from familiarity with and proximity to the local order of drug dealing, their continued commitment to it as adults, despite their experiences of arrest and imprisonment, is reinforced by their inability to secure other means of earning a livelihood. Neighborhood narratives of drug-dealing careers seldom mention incarceration and an untimely death. In the face of these risks, and even the many factors that limit their incomes, they still see drug dealing as the best—or even the only—option available to them.

The interaction-order practices associated with drug dealing offer a deep and shared sense of collective identity and local solidarity. The more embattled people are, the deeper their commitment may become. Neighborhood residents see the same scenarios unfolding, whether they like them or not. By contrast, the motivations of outsiders may be hard to understand. When people feel that outsiders rarely have their best interests in view, the fact that the local order comes from inside and belongs to them may give it a positive value even when it supports activities they do not believe in. In this way, inequality produces enclaves of people who embrace forms of order that protect them from the mainstream—but in so doing maintain or even increase their marginality, thus running counter to broadly democratic principles. By creating the necessity of retreating into protective enclaves, socioeconomic inequality can destroy democracy and generate physical and mental barriers between classes and racial-ethnic groups. Outsiders neither interact with people in these communities nor perceive the conditions that exist there, while at the same time creating policies that simultaneously produce and punish them.

Copyright notice: An excerpt from No Way Out: Precarious Living in the Shadow of Poverty and Drug Dealing by Waverly Duck, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2015 by University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)