“As television news becomes more partisan, more emotional, and leans more toward the trivial, the blame usually falls on venal media moguls and cynical journalists. That's the Way It Is reminds us that the structure of the competitive environment, government regulation, and most importantly the preferences of the audience have always shaped the news we see on TV. This is an important book because it reminds us that even if we don’t like the picture, we are actually looking in a mirror.”–Jack Fuller, former editor and publisher of the Chicago Tribune

Buy this book: That’s the Way It Is

Beginnings

Few technologies have stirred the utopian imagination like television. Virtually from the moment that research produced the first breakthroughs that made it more than a science fiction fantasy, its promoters began gushing about how it would change the world. Perhaps the most effusive was David Sarnoff. Like the hero of a dime novel, Sarnoff had come to America as a nearly penniless immigrant child, and had risen from lowly office boy to the presidency of RCA, a leading manufacturer of radio receivers and the parent company of the nation’s biggest radio network, NBC. More than anyone else, it was Sarnoff who had recognized the potential of “wireless” as a form of broadcasting—a way of transmitting from a single source to a geographically dispersed audience. Sarnoff had built NBC into a juggernaut, the network with the largest number of affiliates and the most popular programs. He had also become the industry’s loudest cheerleader, touting its contributions to “progress” and the “American Way of Life.” Having blessed the world with the miracle of radio, he promised Americans an even more astounding marvel, a device that would bring them sound and pictures over the air, using the same invisible frequencies.

In countless speeches heralding television’s imminent arrival, Sarnoff rhapsodized about how it would transform American life and encourage global communication and “international solidarity.” “Television will be a mighty window, through which people in all walks of life, rich and poor alike, will be able to see for themselves, not only the small world around us but the larger world of which we are a part,” he proclaimed in 1945, as the Second World War was nearing an end and Sarnoff and RCA eagerly anticipated an increase in public demand for the new technology.

Sarnoff predicted that television would become the American people’s “principal source of entertainment, education and news,” bringing them a wealth of program options. It would increase the public’s appreciation for “high culture” and, when supplemented by universal schooling, enable Americans to attain “the highest general cultural level of any people in the history of the world.” Among the new medium’s “outstanding contributions,” he argued, would be “its ability to bring news and sporting events to the listener while they are occurring,” and build on the news programs that NBC and the other networks had already developed for radio. He saw no conflicts or potential problems. Action-adventure programs, mysteries, soap operas, situation comedies, and variety shows would coexist harmoniously with high-toned drama, ballet, opera, classical music performances, and news and public affairs programs. And they would all be supported by advertising, making it unnecessary for the United States to move to a system of “government control,” as in Europe and the UK. Television in the US would remain “free.”

Yet Sarnoff ’s booster rhetoric overlooked some thorny issues. Radio in the US wasn’t really free. It was thoroughly commercialized, and this had a powerful influence on the range of programs available to listeners. To pay for program development, the networks and individual stations “sold” airtime to advertisers. Advertisers, in turn, produced programs—or selected ones created by independent producers—that they hoped would attract listeners. The whole point of “sponsorship” was to reach the public and make them aware of your products, most often through recurrent advertisements. Though owners of radios didn’t have to pay an annual fee for the privilege of listening, as did citizens in other countries, they were forced to endure the commercials that accompanied the majority of programs.

This had significant consequences. As the development of radio made clear, some kinds of programs were more popular than others, and advertisers were naturally more interested in sponsoring ones that were likely to attract large numbers of listeners. These were nearly always entertainment programs, especially shows that drew on formulas that had proven successful in other fields—music and variety shows, comedy, and serial fiction. More off-beat and esoteric programs were sometimes able to find sponsors who backed them for the sake of prestige; from 1937 to 1954, for example, General Motors sponsored live performances by NBC’s acclaimed “Symphony of the Air.” But most cultural, news, and public affairs programs were unsponsored, making them unprofitable for the networks and individual stations. Thus in the bountiful mix envisioned by Sarnoff, certain kinds of broadcasts were more valuable than others. If high culture and news and public affairs programs were to thrive, their presence on network schedules would have to be justified by something other than their contribution to the bottom line.

The most compelling reason was provided by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Established after Congress passed the Federal Communications Act in 1934, the FCC was responsible for overseeing the broadcasting industry and the nation’s airwaves, which, at least in theory, belonged to the public. Rather than selling frequencies, which would have violated this principle, the FCC granted individual parties station licenses. These allowed licensees sole possession of a frequency to broadcast to listeners in their community or region. This system allocated a scarce resource—the nation’s limited number of frequencies—and made possession of a license a lucrative asset for businessmen eager to exploit broadcasting’s commercial potential. Licenses granted by the FCC were temporary, and all licensees were required to go through a periodic renewal process. As part of this process, they had to demonstrate to the FCC that at least some of the programs they aired were in the “public interest.” Inspired by a deep suspicion of commercialization, which had spread widely among the public during the early 1900s, the FCC’s public-interest requirement was conceived as a countervailing force that would prevent broadcasting from falling entirely under the sway of market forces. Its champions hoped that it might protect programming that did not pay and ensure that the nation’s airwaves weren’t dominated by the cheap, sensational fare that, reformers feared, would proliferate if broadcasting was unregulated

In practice, however, the FCC’s oversight of broadcasting proved to be relatively lax. More concerned about NBC’s enormous market power—it controlled two networks of affiliates, NBC Red and NBC Blue—FCC commissioners in the 1930s were unusually sympathetic to the businessmen who owned individual stations and possessed broadcast licenses and made it quite easy for them to renew their licenses. They were allowed to air a bare minimum of public-affairs programming and fill their schedules with the entertainment programs that appealed to listeners and sponsors alike. By interpreting the public-interest requirement so broadly, the FCC encouraged the commercialization of broadcasting and unwittingly tilted the playing field against any programs—including news and public affairs—that could not compete with the entertainment shows that were coming to dominate the medium.

Nevertheless, news and public-affairs programs were able to find a niche on commercial radio. But until the outbreak of the Second World War, it wasn’t a very large or comfortable one, and it was more a result of economic competition than the dictates of the FCC. Occasional news bulletins and regular election returns were broadcast by individual stations and the fledgling networks in the 1920s. They became more frequent in the 1930s, when the networks, chafing at the restrictions placed on them by the newspaper industry, established their own news divisions to supplement the reports they acquired through the newspaper-dominated wire services.

By the mid-1930s, the most impressive radio news division belonged not to Sarnoff ’s NBC but its main rival, CBS. Owned by William S. Paley, the wealthy son of a cigar magnate, CBS was struggling to keep up with NBC, and Paley came to see news as an area where his young network might be able to gain an advantage. A brilliant, visionary businessman, Paley was fascinated by broadcasting and would soon steer CBS ahead of NBC, in part by luring away its biggest stars. His bold initiative to beef up its news division was equally important, giving CBS an identity that clearly distinguished it from its rivals. Under Paley, CBS would become the “Tiffany network,” the home of “quality” as well as crowd-pleasers, a brand that made it irresistible to advertisers.

Paley hired two print journalists, Ed Klauber and Paul White, to run CBS’s news unit. Under their watch, the network increased the frequency of its news reports and launched news-and-commentary programs hosted by Lowell Thomas, H. V. Kaltenborn, and Robert Trout. In 1938, with Europe drifting toward war, CBS expanded these programs and began broadcasting its highly praised World News Roundup; its signature feature was live reports from correspondents stationed in London, Paris, Berlin, and other European capitals. These programs were well received and popular with listeners, prompting NBC and the other networks to follow Paley’s lead.

The outbreak of war sparked a massive increase in news programming on all the networks. It comprised an astonishing 20 percent of the networks’ schedules by 1944. Heightened public interest in news, particularly news about the war, was especially beneficial to CBS, where Klauber and White had built a talented stable of reporters. Led by Edward R. Murrow, they specialized in vivid on-the-spot reporting and developed an appealing style of broadcast journalism, affirming CBS’s leadership in news. By the end of the war, surveys conducted by the Office of Radio Research revealed that radio had become the main source of news for large numbers of Americans, and Murrow and other radio journalists were widely respected by the public. And though network news people knew that their audience and airtime would decrease now that the war was over, they were optimistic about the future and not very keen to jump into the new field of television.

This is ironic, since it was television that was uppermost in the minds of network leaders like Sarnoff and Paley. The television industry had been poised for takeoff as early as 1939, when NBC, CBS, and DuMont, a growing network owned by an ambitious television manufacturer, established experimental stations in New York City and began limited broadcasting to the few thousand households that had purchased the first sets for consumer use. After Pearl Harbor, CBS’s experimental station even developed a pathbreaking news program that used maps and charts to explain the war’s progress to viewers. This experiment came to an abrupt end in 1942, when the enormous shift of public and private resources to military production forced the networks to curtail and eventually shut down their television units, delaying television’s launch for several years.

Meanwhile, other events were shaking up the industry. In 1943, in response to an FCC decree, RCA was forced to sell one of its radio networks—NBC Blue—to the industrialist Edward J. Noble. The sale included all the programs and personalities that were contractually bound to the network, and in 1945 it was rechristened the American Broadcasting Company (ABC). The birth of ABC created another competitor not just in radio, where the Blue network had a loyal following, but in the burgeoning television industry as well. ABC joined NBC, CBS, and DuMont in their effort to persuade local broadcasters—often owners of radio stations who were moving into the new field of television—to become affiliates.

In 1944, the New York City stations owned by NBC, CBS, and Du-Mont resumed broadcasting, and NBC and CBS in particular launched aggressive campaigns to sign up affiliates in other cities. ABC and DuMont, hamstrung by financial and legal problems, quickly fell behind as most station owners chose NBC or CBS, largely because of their proven track record in radio. But even for the “ big two,” building television networks was costly and difficult. Unlike radio programming, which could be fed through ordinary phone lines to affiliates, who then broadcast them over the air in their communities, linking television stations into a network required a more advanced technology, a coaxial cable especially designed for the medium that AT&T, the private, government-regulated telephone monopoly, would have to lay throughout the country. At the end of the war, at the government’s and television industry’s behest, AT&T began work on this project. By the end of the 1940s, most of the East Coast had been linked, and the connection extended to Chicago and much of the Midwest. But it was slow going, and at the dawn of the 1950s, no more than 30 percent of the nation’s population was within reach of network programming. Until a city was linked to the coaxial cable, there was no reason for station owners to sign up with a network; instead, they relied on local talent to produce programs. As a result, the television networks grew more slowly than executives might have wished, and the audience for network programs was restricted by geography until the mid-1950s. An important breakthrough occurred in 1951, when the coaxial cable was extended to the West Coast and made transcontinental broadcasting possible. But until microwave relay stations were built to reach large swaths of rural America, many viewers lacked access to the networks.

Access wasn’t the only problem. The first television sets that rolled off the assembly lines were expensive. RCA’s basic model, the one that Sarnoff envisioned as its “Model T,” cost $385, while top-of-the-line models were more than $2,000. With the average annual salary in the mid-1940s just over $3,000, this was a lot of money, even if consumers were able to buy sets through department-store installment plans. And though the price of TVs would steadily decline, throughout the 1940s the audience for television was restricted by income. Most early adopters were from well-to-do families—or tavern owners who hoped that their investment in television would attract patrons.

Still, the industry expanded dramatically. In 1946, there were approximately 20,000 television sets in the US; by 1948, there were 350,000; and by 1952, there were 15.3 million. Less than 1 percent of American homes had TVs in 1948; a whopping 32 percent did by 1952. The number of stations also multiplied, despite an FCC freeze in the issuing of station licenses from 1948 to 1952. In 1946, there were six stations in only four cities; by 1952, there were 108 stations in sixty-five cities, most of them recipients of licenses issued right before the freeze. When the freeze was lifted and new licenses began to be issued again, there was a mad rush to establish new stations and get on the air. By 1955, almost 500 television stations were operating in the US.

The FCC freeze greatly benefited NBC and CBS. Eighty percent of the markets with TV at the start of the freeze in 1948 had only one or two licensees, and it made sense for them to contract with one or both of the big networks for national programming to supplement locally produced material. Shut out of these markets, ABC and DuMont were forced to secure affiliates in the small number of markets—usually large cities—where stations were more plentiful. By the time the FCC starting issuing licenses again, NBC and CBS had established reputations for popular, high-quality programs, and when new markets were opened, it became easier for them to sign up stations with the most desirable frequencies, usually the lowest “channels” on the dial. Meanwhile, ABC languished for much of the 1950s, with the fewest and poorest affiliates, and the struggling DuMont network ceased operations altogether in 1955.

News programs were among the first kinds of broadcasts that aired in the waning years of the war, and virtually everyone in the industry expected them to be part of the program mix as the networks increased programming to fill the broadcast day. News was “an invaluable builder of prestige,” noted Sig Mickelson, who joined CBS as an executive in 1949 and served as head of its news division throughout the 1950s. “It helped create an image that was useful in attracting audiences and stimulating commercial sales, not to mention maintaining favorable government relations. . . . News met the test of ‘public service.’ ” As usual, CBS led the way, inaugurating a fifteen-minute evening news program in 1944. It was broadcast on Thursdays and Fridays at 8:00 PM, the two nights of the week the network was on the air. NBC launched its own short Sunday evening newscast in 1945 as the lead-in to its ninety minutes of programming. Both programs resembled the newsreels that were regularly shown in movie theaters, a mélange of filmed stories with voice-over narration by off-screen announcers.

Considering the limited technology available, this was not surprising. Newsreels offered television news producers the most readily applicable model for a visual presentation of news, and the first people the networks hired to produce news programs were often newsreel veterans. But newsreels relied on 35mm film and were expensive and time-consuming to produce, and they had never been employed for breaking news. Aside from during the war, when they were filled with military stories that employed footage provided by the government, they specialized in fluff, events that were staged and would make the biggest impression on the screen: celebrity weddings, movie premiers, beauty contests, ship launches. In the mid-1940s, recognizing this shortcoming, producers at WCBW, CBS’s wholly owned subsidiary in New York, developed a number of innovative techniques for “visualizing” stories for which they had no film and established the precedent of sending a reporter to cover local stories.

These conventions were well established when the networks, in response to booming sales of television sets, expanded their evening schedules to seven days a week and launched regular weeknight newscasts. NBC’s premiered first, in February 1948. Sponsored by R. J. Reynolds, the makers of Camel cigarettes, it was produced for the network by the Fox Movietone newsreel company and had no on-screen news-readers. CBS soon followed suit, with the CBS Evening News, in April 1948. Relying on film provided by another newsreel outfit, Telenews, it featured a rotating cast of announcers, including Douglas Edwards, who had only reluctantly agreed to work in television after failing to break into the top tier of the network’s radio correspondents. In the late summer, after CBS president Frank Stanton convinced Edwards of television’s potential, Edwards was installed as the program’s regular on-screen newsreader, its recognizable “face.” DuMont created an evening newscast as well. But its News from Washington, which reached only the handful of stations that were owned by or affiliated with the network, was canceled in less than a year, and DuMont’s subsequent attempt, Camera Headlines, suffered the same fate and was off the air by 1950. ABC’s experience with news was similarly frustrating. Its first newscast, News and Views, began airing in August 1948 and was soon canceled. It didn’t try to broadcast another one until 1952, when it launched an ambitious prime-time news program called ABC All Star News, which combined filmed news reports with man-on-thestreet interviews, a technique popularized by local stations. By this time, however, the prime-time schedules of all the networks were full of popular entertainment programs, and All Star News, which failed to attract viewers, was pulled from the air after less than three months.

In February 1949, NBC, eager to make up ground lost to CBS, transformed its weeknight evening newscast into the Camel News Caravan, with John Cameron Swayze, a veteran of NBC’s radio division, as sole on-camera newsreader. Film for the program was acquired from a variety of sources, including foreign and domestic newsreel agencies and freelance stringers. But Swayze’s narration and on-screen presence distinguished the broadcast from its earlier incarnation. He sat at a desk that prominently displayed the Camel logo and presented an overview of the day’s major headlines, sometimes accompanied by film and still photos, but sometimes in the form of a “tell-story”— Swayze on camera reading from a script. In between, he would plug Camels and even occasionally light up, much to his sponsor’s delight. One of the show’s highlights was a whirlwind review of stories for which producers had no visuals, which Swayze would introduce by announcing, “Now let’s go hopscotching the news for headlines!” Swayze was popular with viewers and hosted the broadcast for seven years. He became well known to the public, especially for this nightly sign off, “That’s the story, folks. Glad we could get together.”

The Camel News Caravan was superficial, and Swayze’s tone undeniably glib, as critics at the time noted. But the assumption that guided its production did not set particularly high standards. As Reuven Frank, who joined the show as its main writer in 1950 and soon became its producer, recalled, “We assumed that almost everyone who watched us had read a newspaper . . . that our contribution . . . would be pictures. The people at home, knowing what the news was, could see it happen.” Yet over the next few years, especially after William McAndrew became head of NBC’s news division and Frank was installed as the program’s producer, the News Caravan steadily improved. Making good use of the largesse provided by R. J. Reynolds, which more than covered the news department’s rapidly expanding budget, the show increased its use of filmed reports, acquired from foreign sources like the BBC and other European news agencies, the US government and military, and the network’s growing corps of inhouse cameramen and technicians. It also came to rely more and more on the network’s staff of reporters, including a young North Carolinian named David Brinkley, and reporters at NBC’s “O-and-Os,” the five television stations that the network owned and operated. In the days before network bureaus, journalists at network O-and-Os were responsible for combing their cities for stories of potential national interest. NBC also employed stringers on whom it relied for material from cities or regions where it had no O-and-Os. Airing at 7:45 PM, right before the network’s lineup of prime-time entertainment programs, the News Caravan became the first widely viewed news program of the television age. Its success gave McAndrew and his staff greater leverage in their efforts to command network resources and put added pressure on their main rival.

The CBS Evening News, broadcast at 7:30, was also very much a work-in-progress. Influenced by the experiments in “visualizing” news that CBS producers had conducted at the network’s flagship New York City O-and-O in the mid-1940s, it was produced by a mix of radio people like Edwards and newcomers from other fields. Most of the radio people, however, were second-stringers. The network’s leading radio personnel, including Murrow and his comrades, had little interest in moving to television. Though this disturbed Paley and his second-in-command, CBS president Frank Stanton, it allowed CBS’s fledgling television news unit to escape from the long shadow of the network’s radio news operation, and it increased the influence of staff committed to the tradition of “visualizing.” With few radio people willing to work on the program, the network was forced to hire new staff from outside the network. These newcomers from the wire services, photojournalism, and news and photographic syndicates brought a lively spirit of innovation to CBS’s nascent television news division. They were impressed by the notion of “visualizing,” and they resolved that TV news ought to be different from radio news, “an amalgam of existing news media, with a substantial infusion of showmanship from the stage and motion pictures.”

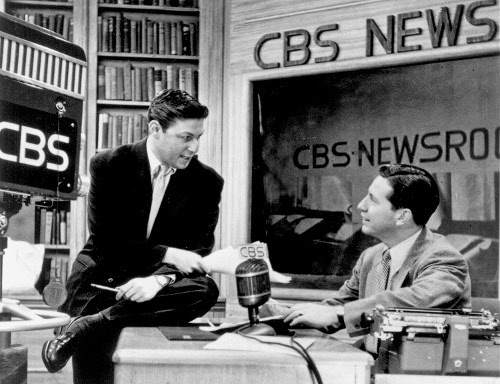

The most important new hire was Don Hewitt, an ambitious, energetic twenty-five-year-old who joined the small staff of the CBS Evening News in 1948 and soon become its producer. Despite his age, Hewitt was already an experienced print journalist, and his resume included a stint at ACME News Pictures, a syndicate that provided newspapers with photographs. He was well aware of the power of pictures, and when he joined CBS, he brought a new sensibility and willingness to experiment. Under Hewitt, the Edwards program made rapid strides. Eager to find ways of compensating for television’s technical limitations, Hewitt made extensive use of still photos and created a graphic arts department to produce charts, maps, and captions to illustrate tell-stories. To make Edwards’s delivery more natural and smooth, he introduced a new machine called a TelePrompTer, which replaced the heavy cue cards on which his script had been written. Expanding on the experiments of CBS’s early “visualizers,” Hewitt devised a number of clever devices to provide visuals for stories—for example, using toy soldiers to illustrate battles during the Korean War. He was the principal figure behind the shift to 16mm film, which was easier and less expensive to produce, and the network’s decision to establish its own in-house camera crews. His most significant innovation, however, was the double-projector system that he developed to mix narration and film. This technique, which was copied throughout the industry, made possible a new kind of filmed report that would become the archetypal television news package: a reporter on camera, often at the scene of a story, beginning with a “stand-upper” that introduces the story; then film of other scenes, while the reporter’s words, recorded separately, serve as voice-over narration; finally, at the end, a “wrap-up,” where the reporter appears on camera again. By the early 1950s, the CBS newscast, now titled Douglas Edwards with the News, was adding viewers and winning plaudits from critics. And it had gained the respect of many of the network’s radio journalists, who now agreed to contribute to the program and other television news shows.

During the 1950s, Don Hewitt (left) was perhaps the most influential producer of television news. He was responsible not only for CBS’s successful evening newscast, but also worked on See It Now and other network programs. Douglas Edwards (right) anchored the broadcast from the late 1940s to 1962, when he was replaced by Walter Cronkite. Photo courtesy of CBS/Photofest.

The big networks were not the only innovators. In the late 1940s, with network growth limited and many stations still independent, local stations developed many different kinds of programs, including news shows. WPIX, a New York City station owned by the Daily News, the city’s most popular tabloid, established a daily news program in June 1948. The Telepix Newsreel aired twice a day, at 7:30 PM and 11:00 PM, and specialized in coverage of big local events like fires and plane crashes. Its staff went to great lengths to acquire film of these stories, which it hyped with what would become a standard teaser, “film at eleven.” Like its print cousin, it also featured lots of human-interest stories and man-on-the-street interviews. A Chicago station, WGN, developed a similar program, the Chicagoland Newsreel, which was also successful. The real pioneer was KTLA in Los Angeles. Run by Klaus Landsberg, a brilliant engineer, KTLA established the most technologically sophisticated news program of the era. Employing relatively small, portable cameras and mobile live transmitters, its reporters excelled in covering breaking news stories, and it would remain a trailblazer in the delivery of breaking news throughout the 1950s and 1960s. It was Landsberg, for example, who first conceived of putting a TV camera in a helicopter.

But such programs were the exception. Most local stations offered little more than brief summaries of wire-service headlines, and the expense of film technology led most to emphasize live entertainment programs instead of news. Believing that viewers got their news from local papers and radio stations, television stations saw no need to duplicate their efforts. Not until the 1960s, when new, inexpensive video and microwave technology made local newsgathering economically feasible, did local stations, including network affiliates, expand their news programming.

The television news industry’s first big opportunity to display its potential occurred in 1948, when the networks descended on Philadelphia for the political conventions. The major parties had selected Philadelphia with an eye on the emerging medium of television. Sales were booming, and Philadelphia was on the coaxial cable, which was reaching more and more cities as the weeks and months passed. By the time the Republicans convened in July, it extended from Boston to Richmond, Virginia, with the potential for reaching millions of viewers. Radio journalists had been covering the conventions for two decades, but with lucrative entertainment programs on network schedules, it hadn’t paid to produce “gavel-to-gavel” coverage—just bulletins, wrap-ups, and the acceptance speeches of the nominees. In 1948, however, television was a wide-open field, and with much of the broadcast day open—or devoted to unsponsored programming that cost nothing to preempt—the conventions were a great showcase. In cities where they were broadcast, friends and neighbors gathered in the homes of early adopters, in bars and taverns, even in front of department store display windows, where store managers had carefully arranged TVs to draw the attention of passers-by. Crowds on the sidewalk sometimes overflowed into the street, blocking traffic. “No more effective way could have been found to stimulate receiver sales than these impromptu TV set demonstrations,” suggested Sig Mickelson.

Because of the enormous technical difficulties and a lack of experience, the networks collaborated extensively. All four networks used the same pictures, provided by a common pool of cameras set up to focus on the podium and surrounding area. NBC’s coverage was produced by Life magazine and featured journalists from Henry Luce’s media empire as well as Swayze and network radio stars H. V. Kaltenborn and Richard Harkness. CBS’s starred Murrow, Quincy Howe, and Douglas Edwards, newly installed on the Evening News and soon to be its sole newsreader. ABC relied on the gossip columnist and radio personality Walter Winchell. Lacking its own news staff, DuMont hired the Washington-based political columnist Drew Pearson to provide commentary. Many of these announcers did double duty, providing radio bulletins, too. With cameras still heavy and bulky, there were no roving floor reporters conducting interviews with delegates and candidates; instead, interviews occurred in makeshift studios set up in adjacent rooms off the main convention floor. Accordingly, there was little coverage of anything other than events occurring on the podium, and it was print journalists who provided Americans with the behindthe-scenes drama, particularly at the Democrats’ convention, where Southern delegates, angered by the party’s growing commitment to civil rights, walked out in protest and chose Strom Thurmond to run as the nominee of the hastily organized “Dixiecrats.” The conventions were a hit with viewers. Though there were only about 300,000 sets in the entire US, industry research suggested that as many as 10 million Americans saw at least some convention coverage thanks to group viewing and department store advertising and special events.

Four years later, when the Republicans and Democrats again gathered for their conventions, this time in Chicago, the networks were better prepared. Besides experience, they brought more nimble and sophisticated equipment. And, thanks to the spread of the coaxial cable, there were in a position to reach a nationwide audience. Excited by the geometric increase in receiver sales, and inspired by access to new markets that seemed to make it possible to double or even triple the number of television households, major manufacturers signed up as sponsors, and advertisements in newspapers urged consumers to buy sets to “see the conventions.” Coverage was much wider and more complete than in 1948. Several main pool cameras with improved zoom capabilities focused on the podium, while each network deployed between twenty and twenty-five cameras on the periphery and at downtown hotels and in mobile units. “Never before,” noted Mickelson, the CBS executive responsible for the event, “had so many television cameras been massed at one event.”

Meanwhile, announcers from each of the networks explained what was occurring and provided analysis and commentary. NBC’s main announcer was Bill Henry, a Los Angeles print journalist. He was assisted by Kaltenborn and Harkness. Henry sat in a tiny studio and watched the proceedings through monitors, and did not appear on camera. CBS’s coverage differed and established a new precedent. Its main announcer, Walter Cronkite, provided essentially the same narration, explanation, and commentary as Henry. But his face appeared on-screen, in a tiny window in the corner of the screen; when there was a lull on the convention floor, the window expanded to fill the entire screen. Cronkite, an experienced wire service correspondent, had just joined CBS after a successful stint at WTOP, its Washington affiliate. Mickelson had been impressed with his ability to explain and ad lib, and he insisted that CBS use Cronkite rather than the far more experienced and well-known Robert Trout. Mickelson conceded that, from his years of radio work, Trout excelled at “creating word pictures.” But, with television, this was a superfluous gift. The cameras delivered the pictures. “What we needed was interpretation of the pictures on the screen. That was Cronkite’s forte.”

When print journalists asked Mickelson on the eve of the conventions what exact role Cronkite would play, he responded by suggesting that his new hire would be the “anchorman,” a term that soon came to refer to newsreaders like Swayze and Edwards as well. Yet in coining this term, Mickelson was referring to the complex process that Don Hewitt had conceived to provide more detailed and up-to-the-minute coverage of the convention. Recognizing that the action was on the floor, and that if TV journalists were to match the efforts of print reporters they needed to be able to report from there as quickly as possible, Hewitt mounted a second camera that could pan the floor and zoom in on floor reporters armed with walkie-talkies and flashlights, which they used to inform Hewitt when they had an interview or report ready to deliver. It worked like clockwork: “They combed through the delegations, talked to both leaders and members, queried them on motivations and prospective actions, and kept relaying information to the editorial desk.” It was then filtered and collated and passed on to Cronkite, who served as the “anchor” of the relay, delivering the latest news and ad-libbing with the poise and self-assurance that he would display at subsequent conventions and during live coverage of space flights and major breaking news. Cronkite’s seemingly effortless ability to provide viewers with useful and interesting information about the proceedings won praise from television critics and boosted CBS’s reputation with viewers.

NBC was not so successful. In keeping with the network’s—and RCA’s—infatuation with technology, it sought to cover events on the convention floor with a new gadget, a small, hand-held, live-television camera that could transmit pictures and needn’t be connected by wire. As Frank recalled, “It could roam the floor . . . showing delegates reacting to speakers and even join a wireless microphone for interviews.” But it regularly malfunctioned and contributed little to NBC’s coverage. More effective and popular were a series of programs that Bill McAndrew developed to provide background. Convention Call was broadcast twice a day during the conventions, before sessions and when they adjourned for breaks. Its hosts encouraged viewers to call in and ask NBC reporters to explain what was occurring, especially rules of procedure. The show sparked a flood of calls that overwhelmed telephone company switchboards and forced NBC to switch to telegrams instead.

Ratings for network coverage of the conventions exceeded expectations. Approximately 60 million viewers saw at least some of the conventions on television, with an estimated audience of 55 million tuning in at their peak. And the conventions inspired viewers to begin watching the evening newscasts and contributed to an increase in their popularity. Television critics praised the networks for their contributions to civic enlightenment. Jack Gould of the New York Times suggested that television had “won its spurs” and was “a welcome addition to the Fourth Estate.”

Conventions, planned in advance at locations well-suited for television’s limited technology, were ideal events for the networks to cover. These were the days before front-loaded primaries made them little more than coronations of nominees determined months beforehand, and the parties were undergoing important changes that were often revealed in angry debates and frantic back-room deliberations. And while print journalists remained the most complete source for such information, television allowed viewers to see it in real time, and its stable of experienced reporters and analysts proved remarkably adept at conveying the drama and explaining the stakes.

Copyright notice: "The Beginnings of TV News," an excerpt from That's the Way It Is: A History of Television News in America by Charles L. Ponce de Leon, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2015 by University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)