< previous part | next part >

Fries to Go, Chaos to Come

Northwest exports head into uncertain waters as economic troubles in Asia start to boil over

Randy Thueson helped fire rockets at North Vietnam when Nixon administration hawks warned that Southeast Asian countries could topple like dominoes to communism.

In April, Thueson launched a load of potatoes at the Far

East as Southeast Asia succumbed to economic contagion that proved more

virulent than political ideology.

Thueson, a wiry man with a trim brown mustache and frizzy gray hair, loaded 20 tons of frozen french fries at a warehouse next to the J.R. Simplot Co. potato-processing plant in Hermiston. Among them were potatoes grown the summer before in Circle 6 of an Eastern Washington farm run by members of the Hutterite religious sect.

He pulled out of the Eastern Oregon city and drove north, crossing the Columbia River on the Interstate 82 bridge. Watching sunlight shimmer on the water below, Thueson’s thoughts drifted to the USS Clarion River, a 201-foot warship that he rode from Cam Ranh Bay, South Vietnam. He likes sending spuds to Asia a whole lot better than rockets.

“Nothing wrong with a little business,” Thueson said, grinning as his Kenworth truck roared.

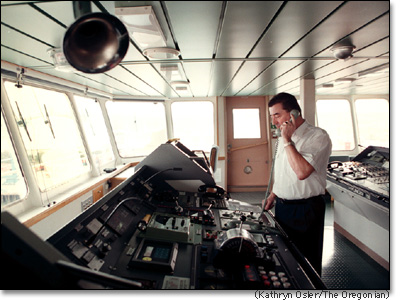

Capt. Hans-Jurgen Hinx mans the bridge of the Dagmar Maersk, which carried the french fries to Southeast Asia. Although Japan’s economy struggled as the vessel passed through, Taiwan’s currency held firm, bolstered by huge foreign reserves.

More than two decades after Vietnam, the United States wages trade, not war, in Asia. Vietnam wants to turn Cam Ranh Bay into a commercial port. The old domino theory has been consigned to the Cold War history books.

But a new domino effect, more widespread and damaging than the imagined syndrome of old, is sweeping Asia. When stocks and currencies plunged in Southeast Asia in the summer of 1997, financial chaos spread throughout the Far East, reversing Asia’s stunning economic rise.

In the summer of 1998, the panic leaped unexpectedly from Asia to Russia and Latin America, as spooked investors withdrew money. It left the United States an oasis of prosperity as the world struggled to stave off a global recession.

“I see it as almost the equivalent of the destruction a war would do,” says Desmond O’Rourke, director of Washington State University’s international marketing program for agricultural commodities and trade.

Economists continue to debate how the contagion spreads and where it will head next. Farmers, processors, truck drivers and sailors live with the fallout.

The Hutterite potatoes—enough to produce about 113,000 large servings of McDonald’s fries—were headed into the Asian economic storm.

Indonesia, where the fries were originally bound, suffered the worst in the spring of 1998. By April, the International Monetary Fund’s bailout package there had almost doubled and reached $43 billion. Five Indonesians died in riots over price increases.

McDonald’s began closing Indonesian outlets, reducing french fry sales. The chain scratched plans to double the number of its 100 Indonesian restaurants in 1998.

The price of a Big Mac tripled to 9,000 rupiah, an amount then worth about $1 in Indonesia’s weakened currency. Many Indonesians could no longer afford fast-food restaurant meals.

Reluctantly, managers at Persico, an independent Illinois company that shuttles fries around the world for McDonald’s, decided to divert the Hutterites’ spuds from Indonesia to Singapore. The Southeast Asian city-state, an island of authoritarian order in a sea of financial chaos, appeared immune from the worst effects of the turmoil.

On April 7, 1998, as Thueson’s Kenworth roared toward Tacoma, many economists thought the worst of Asia’s troubles were over. The week before at the Benson Hotel in Portland, the Bank of America’s international economics director, Emanuel Frenkel, told bank clients to expect a year to 18 months of slower exports to Asia.

Frenkel predicted that Indonesian President Suharto’s administration would prevail. “The alternative, a bloody revolution,” he said, “would be far too costly for all concerned.”

* * *

Thueson downshifted, attuned so precisely to the engine that he never touched the clutch, his left hand steering into a crucial turnoff. Washington 14 headed west from the I-82 bridge over the Columbia, saving about 30 miles on the way to Tacoma.

The plant’s location explains yet another of the myriad ways the Asian economy affects daily life in the Pacific Northwest.

The Washington 14 shortcut would keep Thueson’s round trip under 10 hours, the daily federal driving limit.

J.R. Simplot, founder and chairman emeritus of the Boise company that bears his name, bore the distance in mind when he chose the site of his french fry plant in Hermiston. The plant sat where it was because of Simplot’s trade with Asia.

Thueson remembered his closest encounter with Simplot. The potato magnate sat down at the driver’s table in 1984 in one of the last empty seats of a busy Boise truck stop.

Simplot introduced his wife, Esther. He asked Thueson what he did for the company. “He comes across as a regular guy, but you can tell the wheels are working all the time,” Thueson says.

After breakfast, the multimillionaire and his wife drove off in a 1-ton pickup loaded with a camper. The rig looked 20 years old.

Simplot and Ray Kroc, who built the McDonald’s chain, invented the frozen french fry business during the 1960s. Peeling, cutting and frying raw potatoes in fast-food joints was a time-consuming, expensive process that yielded soggy or overdone fries.

Through mass production, Simplot and Kroc drove costs down and uniformity up. French fries became the second-biggest profit-maker in quick-service restaurants. They even boosted sales of the biggest money machine—beverages. Salt the fries, and customers buy more pop.

Each fall, McDonald’s solicits bids for fries from four big producers: Simplot, Lamb-Weston, Nestle and McCain Foods.

McDonald’s buys fries by weight, for about 30 cents a pound. It sells them by volume, in cheery red cardboard packets. Weigh a large packet of fries, and you realize that U.S. outlets charge $3.65 a pound, a markup of 1,100 percent.

The business is more complex abroad. A high tariff, such as Thailands 54 percent duty, can cut profits. A falling currency, such as the Thai baht, can cripple sales.

By the spring of 1998, Thai students in the United States were struggling to make tuition with the weakened baht. U.S. fry sales in Thailand languished at less than half their level of a year before.

* * *

Crane operators in Tacoma stack containers above a load of Simplot french fries, which rode to Asia beneath a shipment of apples bound for Kuwait. The Dagmar Maersk vessel, which holds 4,633 containers, headed for Asia as many of the region’s economies unraveled.

Thueson rejoined Interstate 82 at Prosser and drove as far as the Central Washington city of Ellensburg before stopping for breakfast.

He eyeballed the trucks tires. The Idaho tags said, “Famous potatoes.”

He checked the temperature of the fries. Still 10 below zero. A thermometer placed next to the fries recorded their temperature from loading to delivery; if the fries got too warm at any point, they would be discarded on arrival.

At Saks Restaurant, Darlene the waitress brought pigs in a blanket, two eggs, black coffee and a smile. After driving a couple of hours, Thueson figured he was already about halfway to Tacoma.

“That’s one of the things that makes this country great,” Thueson said, “is this freeway system.”

“If it wasn’t for that, we wouldn’t be able to compete with anybody else in the world because we’re such a huge country. But we can move goods anywhere in a day and a half.”

Freeways, rails and rivers, which link the Northwest to the Far East, enabled the region to turn toward the Pacific Rim after traditional resource industries faltered. Many containers move by barge to the Port of Portland. But steamship companies subsidize trucking costs to bring Oregon goods, such as Thueson’s load, to Washington ports.

As Thueson’s rig rumbled down Snoqualmie Pass, full containers of Asian goods streamed the other way. Japan and other nations were trying to export their way out of the crisis.

Once unloaded, empty containers from Asia stacked up at Tacoma and other ports along the West Coast, waiting for cargo as U.S. exports declined. Asians could no longer afford to buy as many U.S. products.

The wave of imported goods kept longshoremen working, despite declining exports.

But the trade-off hurt the Northwest economy, setting the stage for a slowdown. Exports support more and better jobs than imports because manufacturing work usually pays better than retail.

Simplot sent about 30 containers of fries a month to Indonesia before the currency plunged. By April, so few containers went to Indonesia that the rare firms still able to produce goods there had trouble shipping them out. Nike Inc., which made almost one-third of its shoes in Indonesia, scrambled for containers to carry them to overseas markets.

Fingers pointed in opposite directions across the Pacific. The Clinton administration expected Japan to rescue the region. U.S. officials urged Japan to bail out its banks and begin importing products from Asia to help out other nations.

In his truck cab, Thueson considered Japan’s recent income tax cut and concluded that it was promising. The idea was to encourage Japanese consumers, known for their ability to save, to spend. The hope was that increased spending would stimulate the economy, reversing the new domino effect and leading Asia back to growth.

But the Japanese, hamstrung by their rigid political system, looked to the United States for a solution. They counted on the world’s big spenders—Americans, the world’s consumers of last resort—to bail out Asia.

American investors partied as the international economic system approached gridlock. The Dow Jones industrial average cleared a record 9,000 points on April 6. It would be four more months before Asias spreading damage would send Wall Street spinning.

The Asian crisis didn’t faze McDonald’s, which operates in 113 countries. The week Thueson drove the container to Tacoma, the company announced plans to invest $1.5 billion expanding in Asia for the next three years.

If anything, Asia’s troubles would help the expansion. Costs of land, labor and supplies would be cheaper because of weakened Asian currencies. “We’re in this for the long haul,” said Jim Cantalupo, McDonald’s International president and chief executive officer.

Thueson pulled up at the Port of Tacoma’s Sealand terminal. He joined a long line of trucks waiting for unloading by unhurried longshoremen.

As in other West Coast ports, Tacoma’s exports to Asia were declining. Maersk Inc., the Danish steamship company that would take the fries to Singapore, had canceled one of its three weekly vessel calls on Tacoma.

Two days later, a crane grabbed the refrigerated container containing the fries from Hutterite Circle 6 and swung it over the 62,700-ton Dagmar Maersk. Built in South Korea in 1995, the ship holds 4,323 containers and 310 refrigerated boxes.

Longshoremen handle the cargo gingerly. Drop a carton of fries, and about one-third of the brittle frozen fingers break. Customers hate short fries.

The crane driver lowered the box carefully below deck. He eased its corner pins into slots at the top of another container of fries headed for Singapore.

Above it, the longshoreman placed a Sealand container of chilled fresh apples headed for Kuwait.

The Hutterites’ spuds were off to Asia.

* * *

The Dagmar Maersk, crewed by Pacific islanders from the Micronesian republic of Kiribati, passed dolphins and orcas a day out of Tacoma.

The ship took the shortest route to Japan. It passed through the Aleutian Islands, skirting the northwest corner of Attu to cross the Pacific Ocean.

As the Dagmar docked April 21 at Yokohama, Japan, officials in Tokyo struggled to save their sinking economy.

The government approved its largest stimulus package ever, $127 billion in tax cuts and public works projects that all but promised to pave over Japan. The Clinton administration immediately called for stronger measures.

The Dagmar steamed on to Shimizu, Japan. It spooked a large turtle in the inland sea.

In Kobe, Japan, crew members took a rare shore leave. Freighters load and unload so fast that for sailors, they can seem like floating prisons.

The ship veered south. On a clear night off Taiwan, lights from thousands of junks and other fishing vessels shimmered on the inky East China Sea.

Taiwan was surviving Asia’s troubles better than most. Its currency held steady, bolstered by Taiwan’s huge foreign reserves.

But to the south in Indonesia, anger erupted as prices continued rising. The middle class increasingly registered quiet support for student demonstrators who called on Suharto to resign.

Rain closed in on the Dagmar in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, one of Portland’s sister cities. It pounded on the bridge’s massive windshield as if sealing the crew into an aquarium.

On April 26 in Hong Kong, Capt. Hans-Jürgen Hinx glared at his chief mate. The fellow German was telling him that the Dagmar Maersk was stuck in port.

This voyage was turning into a string of broken equipment, broken schedules and broken promises. The hulking container ship was falling behind schedule.

Hinx’s bosses weren’t pleased. A ship such as the Dagmar can cost more than $10,000 a day to run, eating into thin profit margins.

Even the point-and-shoot camera that the crew had bought in Long Beach, Calif., was jammed. Now the chief mate was telling Hinx that the emergency beacon had quit.

The beacon spearheads a rescue system that has also gone global. Attached to the top of the ship above the bridge, the beacon breaks free of a sinking ship and floats to the surface. Then it beams a signal up to a Russian satellite and down again to technicians in Moscow, who record the beacon’s location and the ship’s identification number.

The appearance of the young Australian who showed up to replace the beacon inspired little confidence.

Adam Fountain looked more like a shoestring traveler than an engineer. He pulled Walkman earphones from his ears. He brushed water from his dripping beard. He squeezed his sopping, overstuffed backpack into an elevator to the bridge.

Fountain climbed metal steps above the bridge. He fought driving rain to reach the defective beacon, which was bolted to a railing far above the main deck.

Fountain unpacked a small tool case. Suddenly the whole show—the towering ship, the thousands of containers, the ship’s staggering operating cost, the Hutterite french fries bound for Singapore—all came down to a green-handled screwdriver.

Fountain cursed softly. He chipped away layers of rust and paint.

The beacon clicked into place a half hour later. In his office below the bridge, Hinx growled at his crew. Fountain entered with a lengthy, itemized bill.

A burly sailor stuffed new batteries into the ship’s jammed camera, and it began working, too. He pointed it at the captain. Hinx bared his teeth. The camera flashed. The ship was cleared for Singapore.

< previous part | next part >