An excerpt from

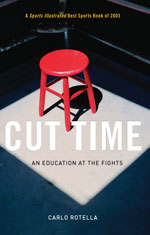

Cut Time

An Education at the Fights

Carlo Rotella

At Ringside

Ringside comes into being whenever the hitting starts and both combatants know how to do it. There is almost always a place on the margins of a fight for interested observers; most fights, even those between drunks in the street, would not happen without them. In the narrow sense, though, ringside requires a ring. Inside a ring, fighting can come under the shaping influence of the rules, traditions, and institutions of boxing. The fight world is grounded in relatively few pieces of real estate—the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York, for instance, or the Blue Horizon in Philadelphia—but it also floats across the landscape, touching down and coalescing in material form when a casino puts up a ring for a night of boxing, or when a trainer rents a storefront and fills it with punching bags and a couple of duct-taped situp mats and a ring for sparring. When the gym loses its lease or when the casino has to clear its hall the next day for a Legends of Doo-Wop concert, the fight world packs up and moves on, traveling light. A ring is just a medium-sized truckful of metal struts, plywood flooring, foam padding, canvas, ropes, cables, and miscellaneous parts; it takes only a couple of hours for a competent crew to assemble it or break it down. While the ring is set up it creates ringside—and the possibility of learning something.

There are lessons to be learned at ringside. Close to but apart from both the action and the paying audience watching it, you see in two directions at once: into the cleared fighting space inside the ropes, and outward at the wide world spreading messily outside the ropes. You must learn specialized boxing knowledge to make sense of what you see in the ring, but the consequences of those lessons extend far beyond boxing. The deeper you go into the fights, the more you may discover about things that would seem at first blush to have nothing to do with boxing. Lessons in spacing and leverage, or in holding part of oneself in reserve even when hotly engaged, are lessons not only in how one boxer reckons with another but also in how one person reckons with another. The fights teach many such lessons—about the virtues and limits of craft, about the need to impart meaning to hard facts by enfolding them in stories and spectacle, about getting hurt and getting old, about distance and intimacy, and especially about education itself: boxing conducts an endless workshop in the teaching and learning of knowledge with consequences.

A serious education in boxing, for an observer as well as a fighter, entails regular visits to the gym, where the showbiz distractions of fight night recede and matters of craft take precedence. Gyms are places of repetition and permutation. A fighter refines a punch by throwing it over and over in the mirror and then at a bag and then at an opponent. A short guy and a tall guy in the sparring ring work out their own solutions to the ancient problem of fighting somebody taller or shorter than oneself. Everybody there, no matter how deeply caught up in his own business, remains alert to the instructive value of other people’s labors. My first and best boxing school has been the Larry Holmes Training Center, a long, low, shedlike building facing the railroad tracks and the river on Canal Street in Easton, Pennsylvania. Holmes, the gym’s owner and principal pugilist, was the best heavyweight in the world in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and he had an extended run as undisputed champion. He has been retiring and unretiring since then, fighting on through his forties and past fifty. His afternoon training sessions at the gym have allowed younger fighters to work alongside a master, and interested observers to watch.

Holmes, the last of the twentieth century’s great heavyweight stylists, practices the manly art of self-defense as it used to be taught. A big, prickly fellow with a no-nonsense workingman’s body and an oddly planed head that seems to deflect incoming shots like a tank’s turret, he has prospered through diligent application of the principle of defense with bad intentions. He puts technique before musculature, good sense before crowd-pleasing drama, perseverance before rage. Boxing is unnatural: instinct does not teach you to move toward a hard hitter, rather than away from him, to cut down his leverage; you do not instinctively bring your hand back to blocking position after you punch with it; almost nobody feels a natural urge to stay on his feet when badly hurt by a blow, or to get up within ten seconds of having been knocked down. Even after a lifetime of fighting, a boxer has to reinforce and relearn good habits in training. Sitting on one of the banged-up folding chairs arranged at ringside in Holmes’s gym, you could pick up some of those habits—or at least an appreciation of them—by watching him at work.

My education as a ringsider probably began at the first school I ever attended, the Ancona Montessori School. I spent the better part of two years there banging a green plastic Tyrannosaurus rex into a blue plastic Triceratops (and then putting them away where they belonged, which is what Montessori schools and well-run gyms are all about), absorbing the widely applicable groundline truth that styles make fights. The gangly T. rex had to risk being gored in order to bite; the squatty Triceratops had to risk being bitten in order to gore; and T. rex had to force the action like a challenger, rather than the undisputed champion among dinosaurs he was supposed to be: he needed meat, while Triceratops could get by on shrubs. Among nonextinct fighters, I knew who Muhammad Ali was, but he was mostly a face and a voice, like Fred Flintstone. The first boxer I recognized as a boxer was Larry Holmes, who was sizing up and solving one contender after another, some- times on television, when I was in high school. Holmes, part T. rex and part Triceratops, had the first boxing style I could see as such. Circling and jabbing, he wore through the other man’s fight like a toxic solvent. A little more than a decade after leaving high school—having gone on to college and graduate school and a first teaching job at Lafayette College, which overlooks Easton from the steep remove of College Hill—I went for a walk to explore the town and found my way down Canal Street to Holmes’s classroom.

I am not saying, as Ishmael says of a whale ship in Moby-Dick, that a boxing gym was my Yale College and my Harvard. I go there to watch, not to train. I’m inclined by temperament to look blankly at a potential fistfighting opponent until he gets bored and goes away, and I’m built physically to flee predators with bounding strides and sudden shifts of direction. Yale and Harvard and other schools like them have, in fact, been my Yale College and my Harvard. You can get an education at ringside, but you also bring your own education to ringside.

I’m currently in something like the thirtieth grade of a formal education that began at the Ancona Montessori School, and somewhere along the way I picked up the habit of research. Visits to ringside and conversations with fight people inspire visits to the archive to pursue context and understanding. The archive of boxing includes a library of edifying and sometimes elegant writing that reaches from the latest typo-riddled issue of Boxing Digest all the way back to a one-punch KO in book 23 of the Iliad, but it also includes many thousands of fights on film and videotape. Seeing a bout from ringside sends me to the VCR with a stack of tapes to study the styles and stories of the combatants, or to consider analogous fights informed by a similar principle: bomber versus tactician, old head versus young lion, showboat versus plumber. I get the tapes in the mail from Gary, an ascetic in outer Wisconsin, and from Mike, a scholar in Kansas with a good straight left who sounds just like a young Howard Cosell (except that Mike knows what he’s talking about). Gary and Mike trade tapes with a motley network of connoisseur collectors, fistic philosophes, and aggression freaks who convene on the Internet to argue over such arcana as whether John L. Sullivan could have coped with Roy Jones Jr.’s handspeed. If the tape-traders’ network can also provide a copy of a bout I attended (not always possible, since I often cover tank-town cards that escape the notice even of regional cable and video bootleggers), I review it to see what cameras and microphones might have caught that I did not.

Even if it begins in the gym, a ringside education has to reckon with television, which has dominated the fights since it rose to power in the 1950s. That’s when boxing began to become an esoteric electronic spectacle rather than a regular feature of neighborhood life (and that’s when A. J. Liebling was moved to write a definitive and already nostalgic defense of seeing a fight in person, “Boxing with the Naked Eye”). From ringside, you can see the signs of television’s dominance. Bouts begin when the network’s schedule requires them to begin; extra-bright lights make everything appear to be in too sharp focus. Announcers, producers, and technicians have a roped-off section of ringside to themselves. Camera operators with shoulder mounts stand outside the ropes on the ring apron, trailing cables behind them as they follow the action. They interfere with the crowd’s view of the fighters, but the inconvenience makes a sort of sense: a few hundred or a few thousand attendees put up with a partially blocked view so that millions, potentially, can see everything.

Not only does TV money dictate the fight world’s priorities, TV technology also promises to turn your living room into ringside. These days, cameras and microphones can bring spectators at home closer to the action than would a ringside seat. When you watch a fight on television, a corner mike lets you horn in on a trainer’s whispered final instruction to his fighter before the bell, and you can see the fighter’s features distort and ripple in slow motion from three different angles as he gets hit with the combination the trainer warned him about. Some part of me knows that this is all deeply intimate and therefore none of my business, even as I pause the tape and then rewind it so I can write down exactly what the trainer said and note the precise sequence of punches.

But television hides as much as it reveals. For one thing, it tells you what to watch. It does not let you turn around to look at the crowd, whose surging presence you can hear, and smell, and feel on your skin at ringside. It does not allow you to look away from the terrible mismatch in the ring to watch for flashes of shame behind the boxing commissioners’ impassivity. It also muffles the perception of leverage and distance, the sense of consequences, available at ringside. You often can’t tell how hard the punches are; occasionally, you can’t tell what is happening at all. After eleven Zapruderine replays, you still ask, Was that a hard shot or a glancing blow? Did it knock him down or did he stumble? Returning to a fight on tape can fill in or correct my understanding of what I saw in person from ringside, and I’m grateful that the boxing archive on videotape has allowed me to see a century’s worth of fights that I could never have seen in person, but I don’t try to score a fight unless I was there in person. I thought John Ruiz was robbed when judges gave the decision to Evander Holyfield in their first fight, but I only saw it on television, so I can’t be sure. Had I been at ringside, I might have concluded that Holyfield hit so much harder than Ruiz that he deserved to win rounds in which he landed fewer blows.

The apparatus of television is not always equal to the task of connecting action to its meaningful context. Television seems to get you close enough to see almost everything and taste the flying sweat, but its appeal lies primarily in cool distance. There’s a basketball game on one channel, a tragic romance on the next, a ten-round bloodbath on the next, and in each case the camera does the equivalent of following the ball, tracing broad emotions and basic narrative contours. For reasons that have as much to do with business as technology, television can’t or won’t capture the off-the-ball struggle of four against five to create or advantageous angles to the basket, or the nearness of another sleeping body in a bed, or the slight changes in distance a smart defensive fighter constantly makes between himself and his opponent to neutralize the other man’s developing punches.

That leaves it up to the on-air announcers to connect action to meaningful context. Talking from bell to bell, they model and parody the processes of education at the fights. When the HBO crew works a bout, for instance, Jim Lampley divides his time between describing the action and mock-crunching the opaque CompuBox numbers that purport to quantify the bout’s progress. Larry Merchant, the professorial one, offers boxing lore and the occasional historical or literary reference. Mostly, though, he makes a smelling-a-bad-smell face I associate with French public intellectuals and explains that the guy who isn’t winning is the more egregious example of how men are no longer men in this debased age. George Foreman, who used to hurt people for a living, is the most sympathetic to the fighters, but wildly erratic and often plain wrong in his commentary. I’m always in some suspense as to how long he can hold back from expressing his obsessive fear of being touched on the chest: “That’s how you take a man’s power.” When moonlighting active boxers like Roy Jones Jr. or Oscar De La Hoya sit in on a broadcast, they seem to be running their thoughts past an internal Marketing Department before articulating them. By the time the profound and useful things they could be telling us about boxing have made it back from Marketing, thoroughly revised, all that’s left is press-release haiku: “Well, Jim, I think they’re / Both great, great competitors / And very fine men.” I always start out rooting for the announcers to break free of the bonds of the form—they are, after all, offering ways to get something out of boxing, which is what I’m doing in this book—but I soon end up wishing they would shut up so I can hear as well as see the electronic facsimile of the fight.

They don’t shut up, though, and anyway, television is a weak substitute for being there, so I go to the fights. It’s better to sit close, and nobody sits closer than ringsiders (who feel the petty little pleasure of having the big spenders and celebrities seated just behind them), so I cover fights for magazines and newspapers. I pick up my credentials at the press table, hang the laminated badge around my neck, and make my way to ringside. At a local club fight, nobody stops me to check my badge; I find an empty press seat at the long table abutting the ring apron and say hello to other regulars. In Massachusetts, where I live now, that means Charlie Ross, the gentle old-timer who writes for the apoplectic North End paper, the Post-Gazette; Mike Nosky, a mailman who moonlights for RealBoxing.com and briefly managed a cruiserweight out of Worcester named Roy “House of” Payne; and Skeeter McClure, who won a gold medal as a light middleweight in the 1960 Olympics, and who used to head the state boxing commission before a new governor’s cronies squeezed him out. At a casino or a big arena like Madison Square Garden, ushers and security guards look over my badge at checkpoints controlling access to ringside, where several rows of tables and seats have been set up to accommodate a small mob of functionaries, reporters from all over, and television people.

In a club or at the Garden, the prefight scene is always fundamentally the same. The ring girls, in bathing gear and high heels, have draped other people’s jackets around their shoulders to keep warm. Guys in suit and tie from the state commission walk back and forth with great conviction, glad-handing and trying to look busy. The referee for the first bout bounces lightly on the ropes to test the tension, then straightens his bow tie. (My favorite local referee is Eddie Fitzgerald, a smiling gentleman with flowing white hair who breaks fighters out of a clinch as if making room to step between them to order a highball. He taps them briskly on the shoulder as if to say, “Gentlemen, there’s no need to fight.”) The promoter walks by, flush and tight, usually managing to make his priciest clothes look like a forty-dollar rental. He stops to rub important people’s necks and shoulders; he points across the room with a wink or a grin to those who don’t merit a stop; he looks over the crowd filling up the hall, pressing in on ringside from all around. Cornermen and old fighters stand in clusters, talking about the time Bobby D got headbutted by that animal out of Scranton. Photographers check their equipment and load film, like infantry preparing to repel an assault. Print and on-line reporters hang around gossiping. Some of the deadline writers have plugged in their laptops to begin laying down boilerplate. It’s always safe to open with something like this:

They said the old pro from Providence couldn’t take it anymore. They said he had taken too many beatings, too many shots to the head. They said he was old. Tired. Washed up.

All washed up.

All he had left was a heart as big as Federal Hill.

Thump thump. Beating with the will to win. Thump thump. And the pride to carry on.

Thump.

Beating.

If the old pro wins, heart conquers all; if the other guy wins, the hard facts of life KO sentiment again. Either way, the lead works. Soon the sound system will play the ringwalk music for the first bout of the undercard, the first two fighters will make their way through the crowd to the ring, and it will be time for the hitting. Then the writers can finish their stories.

At ringside, you feel yourself to be at the very center of something, but you are actually in a gray borderland between the fights and the world. The action in the raised ring happens far away, even when the clinched fighters are almost on top of you, the ropes bowing outward alarmingly under their weight so that you and the others sitting just below all put up your hands at once, like people getting the spirit at church. But neither are you part of the crowd, exactly. At a major fight, ringside expands to a breadth of fifty feet or more and becomes a populous little district in its own right; the crowd, a largely undifferentiated mass, rises into semidarkness somewhere behind you. The people up there paid for their seats (or were comped by a casino, which means they overpaid for their seats); they expect to be entertained. At least in theory, everybody at ringside has a job to do: staging the fight, governing its conduct, bringing news of it to others.

The distinction can collapse, though. At a local fight, ringside can shrink to a couple of feet wide or less. Once, at the Roxy in downtown Boston, when a union carpenter out of Brockton named Tim “The Hammer” Flamos was fighting Pepe Muniz from Dorchester, an especially enthusiastic supporter of Flamos worked his way forward from his seat down to ringside until he was standing between Charlie Ross and the judge seated to his left, bonking their heads with his elbows as he shouted for Flamos to punch to the body. When Flamos pressed Muniz into the ropes on that side of the ring, the guy reached up with incurved hands and helpfully pointed to the exact places on Muniz’s torso he had in mind, his index fingers nearly touching the straining flesh.

This book pursues a ringside course of study at the fights. It follows the progression of humane inquiry, from mystery to learning to mystery again.

Learning at the fights, following the lessons out through the ropes into the wider world beyond boxing, you regularly arrive at the limits of understanding. All sorts of people wrap all sorts of meaning around the fact of meat and bone hitting meat and bone (until one combatant, parted from his senses, becomes nothing more than meat and bone for the duration of a ten-count). The fight world’s specialized knowledge supplies the inner layers of that wrapping: lessons in craft, parables of fistic virtue rewarded or unrewarded, accounts of paydays and rip-offs. Boxing self-consciously takes form around the impulse to discipline hitting, to govern it with rules, to master it with technique and inure the body to its effect. Fight people like to repeat aphorisms, like “Speed is power” or “Styles make fights,” that domesticate the wild fact of hitting. They have plenty of extra-fistic company in this undertaking because the resonance of hitting extends far beyond the fight world’s boundaries. Scholars and literary writers and even crusaders calling for the abolition of boxing wrap it in more layers: not just the conventions of show business and sport, but also social and artistic and psychological significance. And they keep coming because there’s always more work to do. It takes constant effort to keep the slippery, naked, near-formless fact of hitting swaddled in layers of sense and form. Because hitting wants to shake off all encumbering import and just be hitting, because boxing incompletely frames elemental chaos, the capacity of the fights to mean is rivaled by their incapacity to mean anything at all. There is an education in that, too, since education worthy of the name knows its limitations and does not explain things away.

The book begins with introductory courses in the first three chapters, which feature initiations into the fights and trace the traffic between formal schooling and a fistic education. I’m not sure what it says about me and my day job that they also lead in one way or another to college students getting whacked in the eye. The middle three chapters, advanced electives, extend the line of inquiry deeper into the fight world and the careers of seasoned campaigners, who, just as much as spectators, struggle to make hitting mean something. The last three chapters, senior seminars, arrive at limits imposed by age, frailty, and the stubborn meaninglessness of hitting. Toward the end of the book, many of the fighters and their counterparts outside the ring are older—wiser, maybe, but also more damaged.

I do not set out to be comprehensive or chronological; I treat boxing as I have found it at ringside and as it persists in memory. The effect of persistence, the way a fight lives in me and I make use of it, tends eventually to silt over the original experience. I bury a fight like a bone and dig it up from time to time to gnaw on it. After a while, I’m tasting mostly my memory of the original meal, but the exercise has contemplative value, and it’s good for the teeth. Any sort of bout, not just famous ones, can demand such return visits. Some important fights and fighters appear here, but so do obscure set-tos between journeymen almost nobody has ever heard of. Boxers, whether testing themselves against an opponent or shadowboxing in the mirror, are always reminding me that you can get an education out of whatever you find in front of you, wherever you find it.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 1-15 of Cut Time: An Education at the Fights by Carlo Rotella, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2003 by Carlo Rotella. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Carlo Rotella

Cut Time: An Education at the Fights

©2003, 236 pages

Paper $14.00 ISBN: 0-226-72556-1For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Cut Time.

See also:

- A catalog of books in biography

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects