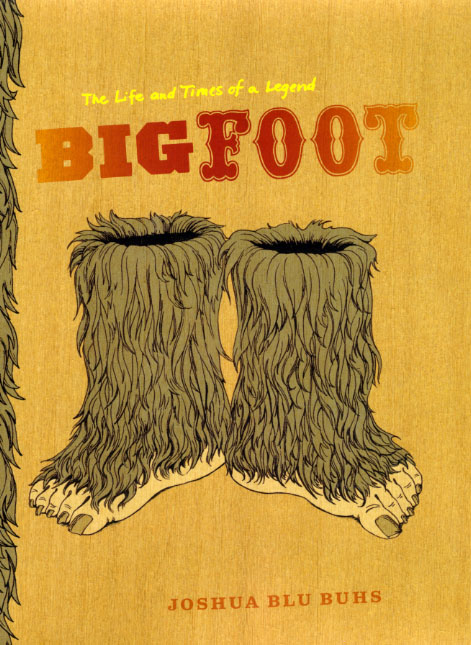

An excerpt from

Bigfoot

The Life and Times of a Legend

Joshua Blu Buhs

Big Foot, 1958

On Monday, August 27, 1958, Jerry Crew left his home in the northern California hamlet of Salyer. Pictures of Crew taken six weeks later show a broad-chested, short-haired man with big glasses, a strong chin, and prominent ears. By all accounts, he was an earnest and sober individual. Crew drove west along California State Highway 299, the chief artery through this montane region, running some 150 miles between Eureka on the Pacific and Redding in the Central Valley. Crew was a catskinner for the Granite Logging Company and the Wallace Brothers Logging Company. The lumber industry employed about one out of every two workers in the county, generating more revenue than the rest of the economy combined.

A few miles on, Highway 299 intersected with Highway 96 at Willow Creek, a gold rush town once known as China Flats and, by 1958, a regional hub that provided services for lumbermen that small towns such as Salyer could not, although by most standards Willow Creek was itself a small town. Like much of the area, Willow Creek was doing fairly well. Since 1949 lumber production in Humboldt County had almost doubled in response to the post–World War II housing boom. Per capita income in the county was on par with the rest of California, and above the national average.

Crew turned north. State Highway 96 followed the Klamath River into the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, crossing into Del Norte County and continuing on to Yreka. Along the highway, strung out between Willow Creek and Yreka like beads on a string, were a number of small towns, Weitchpec and Orleans and Happy Camp. Highway 96 was the main road servicing them, but it was not paved its entire length; Crew’s ride was bumpy and slow. On one side of Highway 96 was a steep drop down to the river, on the other, a rocky cliff face. “Geological maps of the region,” noted nature writer David Raines Wallace, “look … like the results of a jammed conveyor belt…. The ridges [are] not particularly high or craggy, rather a succession of steep, pyramidal shapes” that stretch “almost geometrically into blue distance.” Thick stands of pine, spruce, and fir covered the mountains, ranging down to the water’s edge.

As he drove, Crew passed through the Hoopa Indian Reservation. The bucolic setting and current prosperity masked an ugly history of violence against Native Americans. In February 1860, a group of Eureka men, armed only with hatchets, clubs, and knives, slaughtered the native Wiyots while they were in the midst of a festival, killing women, children, infants, and the elderly. Unapologetic, the Humboldt Times, the local paper, defended the massacre. The U.S. Army gathered the remaining members of the tribe and moved them to the Hoopa reservation, and the region went about trying to forget the horrors of that night.

Just beyond the Weitchpec Bridge, near the confluence of Bluff Creek and the Klamath, Crew turned onto Bluff Creek Road, a timber access route that the Wallace brothers were building on subcontract from the government. Crew had been on this job for two years. About thirty men worked here, whites from surrounding small towns and Hoopa Indians from the reservation. Some women and children were around, too. The commute from Salyer usually took two and a half hours. Many of the other men working on the road moved their families from Happy Camp and Salyer and the other small towns into the forests and lived in trailers during the construction season. Crew, however, returned home each weekend because he was so deeply involved in community and church affairs.

Most of what happened next is recorded only in Marian Place’s On the Trail of Bigfoot. Place was a children’s author and a believer in Bigfoot—sometimes credulously so. She wrote her book almost twenty years after the events of August 27. But she was a diligent researcher and what she reported is as trustworthy as anything else written on Bigfoot—indeed, decidedly more trustworthy than much else. According to Place, Crew saw the foreman, Wilbur “Shorty” Wallace, at the construction site’s main camp and honked his horn lightly. Wallace waved him on. Crew worked at the far end of the road, a quarter mile beyond the camp (about twenty miles from the highway), bulldozing brush and stumps left behind by the loggers who were clearing the path, and roughly grading the land.

Crew parked near his bulldozer, traded his moccasins for work boots, and put on his aluminum hardhat. He noticed a few footprints in the leveled earth but thought nothing of them until he climbed onto his tractor and looked down upon them. The prints were big and manlike. They pressed deeply into the earth. Was someone pulling a prank? he wondered. Crew drove back to tell Shorty what he had seen.

The Folkloric Origins of Bigfoot

Some of the other men working on Bluff Creek Road gathered around and listened to Crew talk with Shorty. They had their own gossip about giant, humanlike tracks to pass on. One man mentioned that similar tracks had been found on another Wallace worksite along the Mad River. Twenty-five workers claimed to have seen those. More tracks had been found in Trinidad, up the coast. It’s unknown whether anyone mentioned it—although it seems likely—but only a few months before the Redding Record-Searchlight had run a story about giant footprints found along a Pacific Gas and Electric Company right-of-way back in 1947.

Shorty suggested that whatever had made the tracks around Crew’s workstation also might be responsible for other … disturbances. The summer before, he said, on a lower section of the road, a 450-pound drum of diesel fuel had gone missing; only its impression and large footprints had been left in the dust. The drum had been found a little while later at the bottom of a gully—into which it must have been tossed, since the foliage on the hillside was unbroken. Not unlike the 700-pound spare tire for the road-grading machine that had somehow found its way into a ditch, Wallace reminded the workers. The men had rescued the tire, and were told that vandals had pushed it. But maybe not. Maybe the tire, like the drum, had been tossed by some thing. Some thing that left immense tracks. Something big and strong. But what?

According to Place, the men debated the possible culprit for a time. There was no consensus about what had made the various tracks, no coherent legend of a mysterious track maker, no Sherpa to tell Crew and the rest what they had seen. Finally, Shorty “winked broadly” and interrupted the debate, telling the men “to be sure to let him know if they saw any apes skedaddling through the timber. Meantime, he’d sure appreciate it if they got to work.”

The men did return to work; they also continued to discuss those tracks and their maker. They called him (and no one doubted that the owner of those large feet was a he) Big Foot, two words. Journalist Betty Allen, who visited the camp in late September, found a bevy of stories about Big Foot. The men accused Big Foot of vandalism, and if something went missing he was the presumed thief. Some of the stories, Allen said, were “hair raisers.” For example, some time in October four dogs were lost, and Big Foot was accused of killing them. Supposedly, a few of the workers and their families did take the tales seriously. Allen reported that some of the men kept “their guns handy at night” because a creature that could toss drums of diesel fuel was something to be feared. But the worriers seem to have been the exception. “A lot” of the tales, Allen said, were “quite fictitious.” They had a “legendary flavor.” When Jess Bemis, another Salyer resident, took a job clearing land on Bluff Creek around this time, he and his wife Coralie joined the fun and, in Coralie’s words, “added fuel to the story by passing on bits of information,” although at the time neither believed Big Foot was real.

Lumberjacks, hunters, trappers, and other working-class men had long told stories of such prodigies. For decades, seasoned veterans had funned greenhorns with tales of sidehill dodgers and mosquitoes so big that they sucked cows dry and by having them fetch the equally legendary left-handed wrench. Or they sent them to hunt snipes. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Eugene Shepard, a Wisconsin lumberjack, raconteur, and prankster, announced that he had caught a hodag, the rhino of America’s north woods. Shepard photographed a group of friends killing the beast with picks and axes. The picture was made into a postcard; hundreds of thousands were sold; tourists flocked to Rhinelander, Wisconsin; reportedly, the Smithsonian even expressed interest. Seeing is believing. But the hodag was just a woodcarving. It was all a humbug. American history is rife with such practical jokes, stories of giant turtles and panthers, jackalopes and sea serpents, agropelters and snow wassetts—an entire bestiary of legendary animals. The tradition continued long after the frontier closed. In 1950, for example, the men’s adventure magazine Saga introduced a feature called “Sowing the Wild Hoax” and encouraged the blue-collar men reading it to send in examples of “particularly fiendish” and “unusually funny” practical jokes.

Figure 11. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Eugene Shepard claimed to have captured a hodag—a legendary beast of the Upper Northwest. This picture was meant as proof, although it was obviously staged. The hodag was part of a long tradition among lumberjacks recounting the exploits of mythical monsters. Tales told about Bigfoot by woodsmen in northern California during the 1950s continued the custom. (Image WHI-36382. Wisconsin Historical Society.)

Over the years, fake footprints have been a favorite hoax and tales of giant wildmen common; this was the folklore—the tales and newspaper reports—that Green and Dahinden discovered and collected. Elgin Heimer, a resident of Myrtle Point, Oregon, probably thought that he was just making a joke, but he expressed an important truth when he suggested to the Humboldt Times that Crew’s mysterious tracks had been left by “Paul Bunyan’s two-year-old boy.” Bigfoot was Paul Bunyan’s heir.

Such joshing, especially among working-class men, served to initiate novices and cement relations on the job. Teasing was a way of testing and proving one’s masculinity—coming up with a joke showed cleverness, withstanding the ribbing (and responding in kind) displayed strength, which was necessary to fitting in. Tales about legendary creatures also helped those who worked far from civilization to manage their anxieties. Inchoate fears about an unknowable nature were congealed into slightly ridiculous forms—the will-am-alone, for instance, was a kind of squirrel that dropped pellets of rolled lichen onto sleeping lumberjacks, causing nightmares—and thus the fear was made to seem absurd, too. In a very real sense, the men and women working and living on Bluff Creek Road told stories about Big Foot to scare themselves silly.

Big Foot Makes the Papers

In the middle of September, a new line of tracks appeared along Bluff Creek road, the first since Crew had found the prints near his bulldozer. A few of the men inspected the tracks and declared that they were neither fake nor the mark of bears. If Crew had once thought that he was the victim of a practical joke, he no longer did. Neither did the Bemises or about a dozen other men. Big Foot, whatever he was, existed. Crew started to hunt it. He also traced one of the giant footprints onto paper and took the rendering to Bob Titmus, a taxidermist in Anderson, not far from Redding.

As Titmus remembered the meeting decades later, he told Crew that the trace lacked too much detail and taught him how to make a plaster cast. Later, Crew called Titmus and said that he had made a cast. It was sixteen inches long. Titmus and a fellow taxidermist, Al Corbett, visiting from Seattle, drove to Salyer and inspected the cast. He was not impressed and suggested—as he said later—“the other workers there at the site had been playing pranks on one another.” Crew insisted that the tracks were real: there were too many, their impressions too deep, their detail too fine. Crew gave Titmus and Corbett a map to his worksite and told them to see for themselves. For one reason or another, the three did not make it to Bluff Creek Road that day.

Around this time, Coralie Bemis sent word of the new tracks to Andrew Genzoli at the Humboldt Times. Genzoli was a Herb Cain-esque columnist who had worked for the Times in the 1930s after graduating from high school, and then set out to see the world. He’d returned in 1948 and had been given the job of writing a column that would be of interest to rural readers. Genzoli named it “RFD.” He was known as an amateur historian—he claimed to have read through most of the paper’s morgue during his first stint with the Times—and peppered his columns with liberal doses of nostalgia for a lost and simpler Humboldt County. Bemis thought that he was the type of person who would be interested in a wildman and might look into the matter; but Genzoli was dismissive, at least at first. He thought that someone was “pulling [his] leg” and set the letter aside. But, when the column that he was writing for September 21 came up short, he decided to print the letter. “Maybe we have a relative of the Abominable Snowman of the Himalayas,” he wrote in his column that day, “our own Wandering Willie of Weitchpec.” It was a fateful moment: like the Yeti and Sasquatch, Big Foot was promoted by the press from local legend to international celebrity.

Genzoli’s column struck a chord. Around dinner tables, in barbershops, at the grocery, people talked about those mysterious tracks. The journalist found himself writing a couple more columns on Big Foot over the next few days, no longer reluctant to publish now that he’d seen there was a lot of enthusiasm for the subject. Big Foot, Genzoli had come to realize, was “good material for a good imaginative writer who is tired of space assignments.” Betty Allen, a resident of Willow Creek, proud grandmother, and correspondent for the Humboldt Times was that writer. Amid the hubbub, she had Al Hodgson, proprietor of Willow Creek’s general store, drive her to the Bluff Creek worksite so that she could investigate the tracks and talk to those who had seen them. She filed a number of articles with the paper about the county’s most mysterious resident.

On the first Saturday of October, Genzoli met Crew; the construction worker had come to Eureka looking for someone who would take his plaster cast track seriously, since Titmus had rebuffed him. Genzoli was impressed by Crew’s demeanor. No longer reluctant to publish, he immediately arranged for Crew to have his picture taken with his trophy for a story, and Crew refused the photographer’s request to smile—“If I did, then someone would accuse me of trickery,” Crew reportedly said. The picture ran the next day, on the front page of the October 6 issue of the Humboldt Times, alongside an article that Genzoli penned (drawing on much of the reporting that Allen had been doing).

Figure 12. Andrew Genzoli (left) and Jerry Crew examine the cast that Crew took of a Big Foot track. Crew’s discovery had the same effect on northern California’s wildman as Shipton’s had on the Abominable Snowman: thrusting the monster into the limelight. This picture accompanied Genzoli’s story in the Humboldt Times. (By permission of Humboldt State University—Special Collections and the Eureka Times-Standard.)

“The men are often convinced that they are being watched,” Genzoli wrote in the article. “However, they believe it is not an ‘unfriendly watching.’ … Nearly every new piece of work … finds tracks on it the next morning, as though the thing had a ‘supervisory interest’ in the project.” Either Genzoli or Allen also interviewed Ray Wallace, Shorty’s brother and one of the Wallaces running the logging company, who claimed to have measured the creature’s stride: fifty inches while at a stately pace, nearly ten feet while running. Someone had also contacted Titmus, who by now had been out to the worksite and revised his previous opinion: these tracks had not been faked, he said. “Who is making the huge 16-inch tracks in the vicinity of Bluff Creek?” Genzoli wondered. “Are the tracks a human hoax? Or, are they the actual marks of a huge but harmless wild-man, traveling through the wilderness? Can this be some legendary sized animal?” Genzoli called the mysterious track maker Bigfoot, one word, which he thought played better in newspapers.

Years later, Genzoli said that he thought that the tale of Crew’s giant plaster cast and rumors about the mountain wildman “made a good Sunday morning story.” But it was more than that. It was a sensation—more so, much more so, than the publication of Bemis’s letter had been. The article was sent over the newswires and, like the tracks that Shipton found on the head of the Menlung Glacier, Crews’s cast caught the world’s imagination. “On Monday, Tuesday, and for the rest of many days,” Genzoli said, “we had reporters from all the wire services pounding on our doors. There were representatives from the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Chronicle and Examiner, San Francisco [sic], and many, many more.” Less than two weeks after the article appeared, the television game show “Truth or Consequences” offered $1,000 to anyone who could explain how the tracks had been made. In the year after Bigfoot’s big debut, Genzoli received more than 2,500 letters. Here was an Abominable Snowman—not inhabiting the frigid, faraway Himalayas, but in California! Here was Bigfoot.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 66–75 of Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend by Joshua Blu Buhs, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2009 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Joshua Blu Buhs

Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend

©2009, 304 pages, 35 halftones

Cloth $29.00 ISBN: 9780226079790

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Bigfoot.

See also:

- An interview with the author

- Our catalog of biology titles

- Our catalog of history titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog