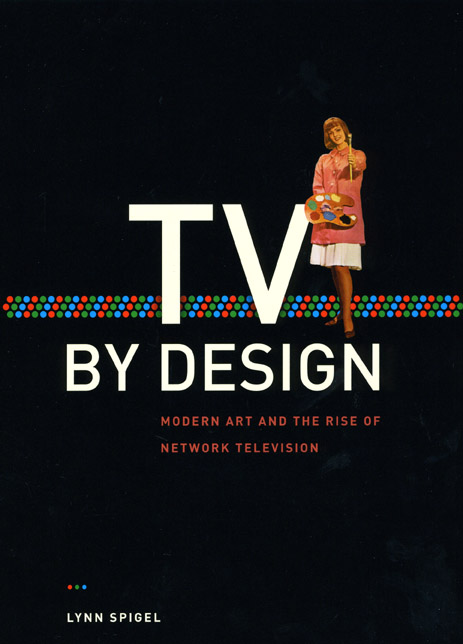

An excerpt from

TV by Design

Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television

Lynn Spigel

From Chapter 2

An Eye for Design: Corporate Modernism at CBS

In 1948, CBS commissioned photographer Paul Strand to illustrate a trade advertisement aimed at prospective sponsors. Accompanied by the caption “It Is Now Tomorrow,” Strand’s photograph depicts television antennas looming over the New York City skyline. The antennas dominate the composition while skyscrapers located at the very bottom of the frame appear dwarfed, as if in miniature, and sinking out of sight. By making television the central attraction in a vanishing city, Strand’s photograph gets to the heart of the CBS sales message: in the postwar marketplace, the new electronic landscape of television will be more important to commerce than offices, shops, or any other physical place in the urban environment. The accompanying ad copy underscores the point by promising sponsors that companies that advertise on CBS television will “make sharp and lasting impressions” on audiences “today and tomorrow.”

Paul Strand, “It Is Now Tomorrow” (1948). Reprinted with permission of CBS. |

|

The use of fine art and art photography in advertising was in itself nothing new, and CBS was certainly not the first corporation to dabble in the arts. As Roland Marchand demonstrates in his history of public relations, over the course of the 1920s and through the 1940s, U.S. corporations often employed fine artists and sponsored museum and fair exhibitions in order to associate their companies with good taste and democratic ideals of enlightenment. For a regulated industry like broadcasting, the use of art in advertising was particularly important for convincing the FCC of the medium’s higher purpose. So too, according to Marchand, art’s ability to give a company a respectable reputation helped alleviate the problems of “scale” for national corporations; in other words, national companies could appeal to local populations by promising to support local cultural institutions and to provide national standards of excellence for people in small towns and big cities alike. This issue of scale was especially important to broadcasting networks whose business depended on providing national programming to local affiliates and markets. Indeed, despite its urbane sensibility, the design ethos at CBS was rooted in the need to create a nationwide standard of excellence that would nevertheless appeal to the indigenous and specific tastes of affiliate station managers and their local audiences (a goal which, as we shall see, was often fraught with tension). Finally, by associating itself with the arts, a corporation could build a forward-looking workforce. In the 1940s, the Container Corporation of America used fine art in corporate ads designed to “attract to their organization young and modern-minded employees and to show that Container Corporation is ahead of its times.” With similar aspirations, CBS and NBC both commissioned artists in the 1940s to promote their radio networks. In the 1930s, CBS’s design ethos was already wedded to its image as an arbiter of progress. Paley’s right-hand “concept man” Paul Kesten (who came to the radio network from a career in advertising) was described by one associate as “vice-president in charge of the future.”

Corporate advertising especially flourished during the 1950s when it merged with the growing field of modern design (both graphic design and architecture). Corporate identity programs were important to the development of multinational corporations that sought to communicate with a universal visual language (trademarks, trade dress) across cultures and through time. In his book, The Corporate Personality, design consultant Wally Olins notes that designers produced identity programs that made their clients appear “modern” and “cool” but also “ordered,” “homogeneous,” and “controlled.” As a modern mass medium bent on selling an image of itself as both a rationalized business and cutting-edge technological marvel, television was particularly suited to this double vision. As television grew in influence, the medium became a central workplace for artists (photographers, typographers, graphic artists, fine artists) who found employment in art departments at networks, broadcast stations, and advertising agencies. These artists gave networks a public face just as much as any single TV program did. Corporate trademarks like the CBS eye and NBC peacock gave the abstract business of networking a tangible visual look that was instantly recognizable to business clients and audiences alike.

This chapter explores how television networks—especially CBS—created a new visual environment for their business operations by turning to the world of modern graphic design. My argument is simple: the rise of television as both a business and cultural form can’t be understood simply through the standard accounts of sales statistics, network-affiliate contracts, ratings, program planning, business deals, and policy decisions. Instead, the rise of the television industry must also be considered—as it was by the business culture of the time—from the point of view of visual design. Television executives were in the business of visual communication; as visual communicators, they had to convince their business clients and the general public that they understood how to make good images. To be sure, as visual communicators themselves, advertisers were intensely interested in how well their products would be displayed on TV. In order to present their best public face (and so attract advertisers and audiences alike), network executives devoted considerable resources to trademarks, corporate advertising, newspaper ads, and on-air graphics. In the field of modern design, CBS served as an example for the other networks and broadcasters, and even more extensively, CBS influenced the larger field of corporate advertising and graphic design. In addition, these forays into modern design helped shape the general public’s perceptions of television as a new and modern media form. When people watched TV or read newspaper promotions for TV programs they inevitably also encountered modern design. Modern design was a crucial part of the television image and the cultural experience of watching TV.

The lack of attention to modern design among broadcast historians has resulted in a number of untested truisms about what the TV experience was for viewers. Most historians assume the TV experience was programs and stars. From this perspective, broadcast historians usually reach back to a “golden age” of vaudevillian variety shows, Broadway-influenced anthology dramas, radio-influenced news and public-affairs shows, and a sprinkling of programs featuring famous personalities, most of whom came from film, vaudeville, radio, and/or newspapers (e.g., Arthur Godfrey, Lucille Ball, Ed Sullivan). Although broadcast historians aren’t wrong—indeed, television programs did evolve from previous entertainment and information forms—the singular focus on programs blinds us to the variety of visual experiences that early TV actually offered. Insofar as television was not just programs but also trademarks, advertisements, credit sequences, and station graphics, the people who watched television (or saw publicity for TV shows), were also witnessing cutting-edge developments in the art of modern graphic design. In this sense, rather than just transporting viewers back to older entertainment forms (like vaudeville or Broadway or radio), television also taught viewers how to see these older forms within a modern visual context. Just as modern stage design revitalized the variety show’s “vaudeo” style, modern graphic design reconfigured the old media for the new.

My aim in this chapter is, then, twofold. First, I consider how television executives of the 1950s used modern design to build their businesses. Second, I examine how corporate advertising created a modern visual look for television as a new media form, different from the forms of the past. As the leader in the field, CBS was a center for all this activity, but, as we shall see, it was not alone.

The Tiffany Network and the Design Context

After WWII, when television began to be a commercial reality, the CBS network made a concerted effort to distinguish itself as the “Tiffany Network,” a prestige organization with quality appeal. As many broadcast historians have noted, it did this in part by hiring star talent away from NBC, by creating a topflight news division, and (as we have already seen) by producing public-affairs programs. But even while CBS was known for its news division and quality showmanship, the bulk of programming on CBS did not really look all that different from that offered on its major competitor, NBC. NBC’s Sylvester “Pat” Weaver also espoused ideals of quality programming and, as his “Operation Frontal Lobes” initiative suggests, he was heavily invested in promoting cultural fare. Rather than opting for high or low per se, both major networks (and to a lesser degree even the more fledging ABC network) offered an eclectic mix of cultural programming and public-affairs shows along with more popular genres like soap operas, sitcoms, and police shows. Moreover, even while CBS continued to promote itself as a prestige organization, over the course of the 1950s the network actually became the bane of TV critics after canceling many of its public-affairs programs (like See It Now) in favor of churning out higher rated but more formulaic westerns, sitcoms, and quiz shows (the latter of which resulted in the famous quiz show scandals).

In this regard, CBS’s reputation as the Tiffany Network was less a function of its programs per se than it was of the way the programs were promoted and packaged. Graphic design and publicity art were especially crucial to CBS’s ability to distinguish itself from other networks and convince elite business clients on Madison Avenue of its quality appeal. In the 1950s CBS television created a unique corporate brand by using modern graphic design and fine art to promote its products and services. So successful was CBS in creating a prestige image and in attracting audiences and sponsors that by 1953 it became the number one network in program ratings and advertising sales, a position it occupied throughout the decade and into the early 1960s. Moreover, by 1954 CBS was not just the leading U.S. television network; it was also the largest advertising medium in the world.

The network’s focus on modern design was in part inspired by the tastes of its leadership. Not only was chairman William S. Paley an art collector with an impressive array of French impressionist and post-impressionist paintings, he also sat on the board of MoMA, and even (dubiously) claimed to be a personal friend of Henri Matisse. His office at CBS was adorned with the works of great European masters, which shared the space with his television set and many broadcast awards. Second in command, CBS president Dr. Frank Stanton was even more knowledgeable about art, and he was also passionately interested in architecture and furniture design. Stanton’s office was notorious for its minimalist modern design complete with Mies Van de Rohe chairs, a marble table (in place of a desk), and modern artworks including a wood relief by Jean Arp, sculptures by Alberto Giacometti and Marino Marini, and an abstract oil painting by Pierre Soulages. Reporters consistently described both Paley and Stanton as sophisticated, urbane men whose tastes in clothing, cars, and even women exhibited their progressive outlook. In 1950, when Time magazine featured a cover story on Stanton, the reporter commented not only on his business expertise but on his five bedroom New York apartment that “glitter[ed] with glass, polished woods, and geometric abstractions” and looked “a little like a wing of the Museum of Modern Art.”

Although Paley and Stanton had a direct impact on the CBS “look,” the network’s investment in modern design wasn’t based solely on the personal tastes of its directors. Instead, like Weaver at NBC, Paley and Stanton were primarily concerned with building their network’s reputation and revenues. In forging a business strategy for television, they used modern art and design as tools for that greater purpose. Paley and Stanton thought that the best way to promote the quality of their products and services was to associate the network with artistic excellence. Modern design especially suited the demands of a television network that needed to exude an aura of technological progress. As Stanton claimed:

I think there are few needs greater for the modern, large-scale corporation than the need for a broad public awareness of its personality—its sense of values.… Everything we produce at the Columbia Broadcasting System, including our own printed advertising, reports, documents, and promotion, is carefully considered from the viewpoint of the image we have of ourselves as a vigorous, public-spirited, profitable, modern enterprise. We give the most careful attention to all aspects of design. We believe that we should not only be progressive but look progressive. We aim at excellence in all the arts, including the art of self-expression.

Given that CBS was advertising to advertisers, the need for artistic excellence was even more critical. As Stanton recalled in 1962, “Distinction in advertising was a quality essential to the growth of CBS. As media ourselves, we could not afford to place in other advertising media less than first-rate art and copy.”

Stanton’s observations were especially germane to the context in which he worked. In 1954, Sponsor conducted a survey of how executives at advertising agencies felt about ads for television stations. According to the findings, most agency executives believed “station advertising lacked imagination and some thought it was downright dull.” Sponsor reported that station advertising often presented factual information (such as ratings) that didn’t necessarily convince sophisticated advertisers to buy advertising time on the channel. In other words, station advertising often took the market research approach over the design orientation. The case of CBS is particularly interesting in this regard because Stanton was not just an art lover; he also had a Ph.D. in psychology, specializing in the subject of audience retention of media messages. In the late 1930s, before coming to CBS, Stanton worked with audience research pioneer Paul Lazarsfeld to create the “Program Analyzer,” one of the first audience research measurement devices. Given his pedigree, Stanton took market research extremely seriously, yet he believed that research alone would not address the challenges faced by a media corporation that needed to persuade other media executives to buy its services. As Stanton knew, the sponsors to whom CBS aimed its corporate ads had their own market research departments, so they could easily see through network advertisements with trumped up claims about program ratings. For this reason, Stanton and his colleagues at CBS thought that advertisers needed to be motivated by something else besides market research data, and that something else was modern design.

“Cheesecake” advertisements like this used women to woo sponsors (Sponsor, 1955). |

|

In the late 1940s Stanton created a brand for CBS by making all visual representation of the network an in-house operation. Rather than the typical practice of hiring an advertising agency to promote the business, CBS created its own advertising and promotions department that fully controlled CBS’s corporate image. In 1951, Stanton appointed William Golden to be creative director of advertising and sales promotion for the CBS Television Network. The title signaled that Golden was more than an advertising art director (the position he already occupied at CBS), but rather in charge of all visual materials—from program advertisements to trademarks to advertising rate cards for the sales department to annual reports for the research department to corporate stationery to aspects of building and studio design. Golden not only controlled all facets of CBS’s visual look, his designs were actually produced in-house by the CBS production department. The only task that CBS farmed out was the placement of ads in print media (in the 1950s this was done by the McCann-Ericsson agency). As CBS’s major competitor, NBC also hired prominent graphic artists (many working in the modern style), but no single art director at NBC controlled the network’s image in the way Golden did at CBS. As a result, NBC’s image was never so visually coordinated. Comparing the two leading networks in 1953, Fortune observed that whereas NBC (under its parent company RCA) had more success securing control over the hardware (for example, RCA had just won the patent for its color system in a bitter war with CBS), CBS was the leader in “showmanship” and “the graphic arts.”

In addition to advertising to business clients, Golden and his staff designed program promotion (including newspaper ads as well as on-air slides and trailers) and sent these promotional materials in readymade publicity kits to CBS’s owned and operated (flagship) stations and to affiliate stations across the country. Flagship and affiliate stations in turn used Golden’s art to promote themselves (and CBS programs) in newspaper ads and on TV itself. This meant that even while Golden’s primary relationships were with business clients, his artwork was widely seen by the general public. Anyone who watched CBS TV or read the TV section of their local paper would have seen at least some of the designs produced by Golden and his staff. As Stanton claimed in 1953, in addition to advertising to advertisers, the art director is also “advertising to the public to persuade them to listen to and view these programs.”

Golden was well seasoned for this complex job. Golden began his career as an advertising artist at the Los Angeles Examiner in 1929, and by 1936 Dr. M. F. Agha, the widely revered art director at Condé Nast publications, invited Golden to join the staff at House & Garden. One year later, Golden left the magazine to take a job at CBS, and in 1940 he was appointed art director of the radio network. Requesting a temporary leave of absence from CBS in 1942, Golden worked in the Office of War Information and served as art director of army training manuals. After the war, in 1946, Golden resumed his work at CBS, and from 1951 until his death in 1959 he and his staff created a distinct visual look for the network. Having worked at House & Garden, Golden had a particular knack for designs that would attract a “mass” audience, and especially the all-important female consumer, but at the same time his clean, modern designs spoke to a “class” sensibility that associated the network with dignified tastes. His ability to speak to a broad public in a visual language that nevertheless articulated class aspirations was essential to the CBS Tiffany brand. By the end of his short life (he died at the age of forty-eight), Golden had received numerous awards from professional organizations and, as the inventor of the CBS eye, was generally recognized as one of the leaders in the field of modern design. As Stanton claimed, “Bill Golden was our relentless master in the pursuit of the first-rate.”

Golden’s rise to prominence at CBS was in part a function of the larger changes taking place in the world of advertising and graphic design. Although many of the leading advertising firms of the 1950s grew profoundly dependent on market research, as we saw in chapter 1, by the mid-1950s modern graphic design was not only routinely used in corporate advertising, it was also becoming centrally important to consumer advertising. In fact, while business historians have often characterized the 1950s as the “dark age” of creativity in advertising, not all advertisers wanted to be the proverbial “man in the gray flannel suit,” as the title of Sloan Wilson’s 1955 bestselling novel about uncreative money-grubbing ad agents suggested. Rather than discounting creativity, trade journals such as Printers’ Ink, Art Direction, Print, and Sponsor ran feature stories on art directors and graphic designers, elevating their status in the field. Most aggressively, professional organizations promoted the field of modern design. Established in 1914 and 1920 respectively, the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) and the Art Director’s Club (ADC) grew in prominence after World War II, and they often collaborated with fine-art venues.

In 1941, when Golden was employed at CBS radio, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened its galleries to advertising artists for the first time by hosting the twenty-first annual exhibition of the New York ADC. Golden’s advertisement won an ADC medal in the category of black-and-white photographs. The event itself marked the growing relationship between the fine and commercial arts, as well as their publics. Museum president William Church Osborne presided over the opening ceremonies for the exhibition, praising the high quality of the advertising art on display. According to the New York Times, he regarded the exhibit to be an important event for the museum and he even “attributed to advertising much of the country’s increased interest in art.”

The Museum of Modern Art also contributed to the prominence of graphic design and commercial art, both in its own museum publications (that were designed by such prominent graphic artists as Will Burtin) and in exhibitions it held for the ADC. For the 1949 ADC exhibit, MoMA displayed the advertising art in tight patterns within gray-framed plaques (mounting the ads as authentic art), and the entire exhibit was televised under the auspices of architect Philip Johnson. In her review of the exhibit, New York Times art critic Aline B. Louchheim singled out a CBS radio advertisement illustrated by renowned Depression Era artist Ben Shahn and executed under Golden’s direction. Titled “No Voice Is Heard Now…” the advertisement was a black-and-white line drawing of empty chairs for the CBS orchestra, evoking radio’s musical presence through the absence of human form. While figural and whimsical, the ad nevertheless had a modern abstract feel; its allusion to the CBS orchestra via the idea of absence was a highly conceptual way to invoke radio’s imaginary presence in the home. Describing this ad, Louchheim compared it to the work of a modern master. “In the line drawings of William Golden… and by Ben Shahn—I see the influence of Paul Klee tempering the conventional cartoon. To this reviewer, the black and white work of this kind was outstanding in the exhibition.” Noting how other ads in the exhibit echoed Miro, Arp, and Mondrian, Louchheim spoke of the “class” vs. “mass” audience attracted to this kind of abstract and conceptual copy.

More generally, during the 1950s, universities and art exhibitions encouraged contacts between graphic design and fine art. In July of 1950, Yale University announced its creation of a new Department of Design with painter/designer Josef Albers as chairman. By 1958, Print reported that there were “approximately 100 schools of art and design in the United States” and that “design schools in America today are attaining and offering a new thinking, a new standard” geared more to “technological advances” and “art theory” than the old courses in decorative arts. Meanwhile, commercial artists often exhibited their work in New York City art galleries after it appeared in print, and these exhibitions were “quite a lively success.” The AIGA mounted small shows that featured, for example, Saul Bass’s film posters and record covers, Paul Rand’s ads and package designs, Boris Artzybasheff’s covers for Time magazine, and Shahn’s posters and advertising illustrations. A member of the AIGA, Golden was chairman of its “Design and Printing for Commerce” exhibition, and in 1954 he inaugurated the “50 Advertisements of the Year Show” that promoted modern design.

The establishment of the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was especially important to America’s stature as a world leader in design. Held in 1951, the inaugural conference was a landmark occasion. Walter Paepke of Container Corporation of America initiated and sponsored the conference along with his company’s art director, Egbert Jacobson. Frank Stanton of CBS was among the numerous prominent business leaders who attended. Other participants included prominent architects such as Eero Saarinen (who went on to build CBS’s Black Rock), graphic artists and typographers such as Herbert Bayer (chairman of design for Container Corporation of America), and art directors and illustrators like Leo Lionni (who took over Will Burtin’s reign as art director at Fortune in 1949 and often worked for CBS). Over the course of the 1950s and 1960s, the IDCA focused on a variety of themes pertinent to the relationship between modern design and business. Speakers came from diverse fields such as fine arts, behavioral science, education, engineering, theater, motion pictures, sociology, economics, history, philosophy, semantics, business, psychology, and architecture.

Through all of these venues, the growing field of modern design created a context for television’s own visual repertoire that had important ramifications for the medium’s rise and the public’s ways of looking at it. Even while many television programs harked back to older entertainment forms, CBS used modern graphic design to promote television’s status as the arbiter of a new progressive and sophisticated postwar culture. Nevertheless, tensions between modern art and mass sensibilities ensued.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 68–79 of TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television by Lynn Spigel, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Lynn Spigel

TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television

©2008, 402 pages, 52 halftones

Cloth $27.50 ISBN: 9780226769684

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for TV by Design.

See also:

- Our catalog of media studies titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog