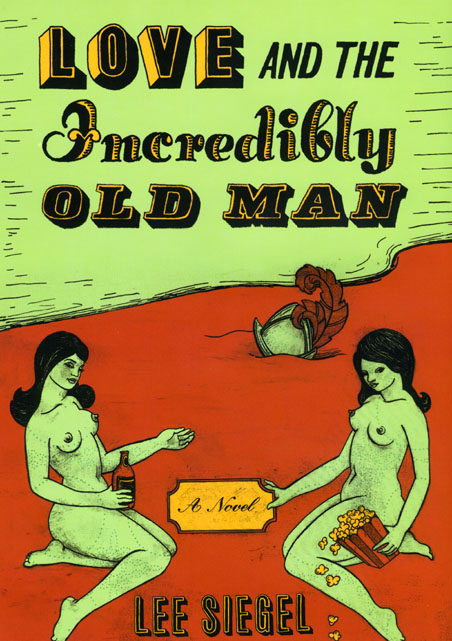

An excerpt from

Love and the Incredibly Old Man

A Novel

Lee Siegel

Preface

2005

an introduction to juan ponce de león

The Fountain of Life in the Garden of Eden truly existed as a real material fountain, and from that Fountain a real river flowed out of Paradise. We should be persuaded to believe that all that is narrated in this book actually happened. But the facts do also have significant figurative meanings.

saint augustine, De genisi ad litteram

(On the literal interpretation of Genesis)

21 June 2005

Dear Mr. Siegel,

I introduce myself here with no expectation that you will believe me, but with some hope that you might be inclined to trust in my sincerity. Incredible as it may seem, I am, in fact, none other than Juan Ponce de León, the Spanish explorer who, at the age of forty-eight, on an Easter Sunday in 1513, discovered the land I christened Pascua de Florida. While duly acknowledging that achievement, historical accounts have ridiculed me for a credulity which, they imagine, encouraged a vain quest for the legendary Fountain of Youth. The fact is, however, that I did, much to my own astonishment, actually unearth a very real artesian wellspring, the miraculous waters of which did indeed, until very recently, have the power to render living beings essentially immune to illness and resistant to the process of aging.

Subsequent to a series of dramatic events that led people to believe that Juan Ponce de León died in Cuba in 1521 and now rests in peace in Puerto Rico, I have, for almost five hundred years, continued to live incognito, perennially healthy and rather consistently happy, at the site of the Fountain of Life in a fertile garden in Eagle Springs, Florida, a place known as Haveelaq to the Zhotee-eloq tribe of Carib Indians who first greeted me here. It is the Gan Eden of the Hebrews and the

hortus deliciarum of the Christian cartographers who had located Paradise rightly in the Indies, but wrongly in the Eastern ones.I am, at this time, rather woefully aware that, alas, after all these years, the end is at hand. The Fountain of Life has run dry. One by one, the eagles in the Garden have disappeared, and the once lush vegetation has begun to wither away. I understand and accept that this is in accordance with an intractable law that all things, inanimate and animate alike, the hardest stones as well as the most delicate blossoms, indeed the entire cosmos no less than you and I, Mr. Siegel, must ultimately deteriorate, disintegrate, and evaporate into oblivion.

Sanguine and enthusiastic as I have always tried to be, however, I do hope to last at least long enough to celebrate my five-hundred-and-fortieth birthday on the twenty-second of July of this year. While I have never allowed myself the fantasy that the Fountain would permit me to live forever, I am, I must concede, somewhat disappointed about having to pass away so soon. Five hundred and forty years may sound like a long time to you, but it is not anywhere even near forever. Isn’t it irksome that the most obvious platitude, the tritest and most trivial truth that “we all have to go someday,” turns out to be the most absolute and profound knowledge, and that all other truths are secondary to, and contingent upon, it?

At this point I find myself hoping to discover some solace and consolation in telling my story and, by so doing, reminding myself that I have, after all, and for the most part, had a very good time for a very long time that only just now seems not nearly long enough. From time to time over the last half millennium, I occasionally imagined that someday I’d be ready and even content to die. Once in a while I’d suppose that death might, at some point, become a tenable alternative to life. But, in fact, the longer I have lived, the more I have longed to live longer and longer.

It both touches and amuses me to know that there are people who declare, and perhaps even imagine it to be true, that it would somehow be a burden to live forever and that death is some sort of deliverance. They make believe that mortality provides an opportunity for redemption and even access to some sort of eternity. I suspect that such farfetched fancies help some people accept an essentially unacceptable reality. All of us, although few will own up to it, even to ourselves, want to be deceived in matters of death no less than in matters of love. But deep down don’t we all know that to die, whether from mishap, violence, disease, or old age, is a pity? And love, contrary to what so many have rhapsodized, only makes death all the more lamentable. I can assure you from my own experience that to stay young and live long is good, very good, and the younger and longer the better. That is, I suppose, why death is so annoying.

Again, I do not imagine that you will be inclined to believe me. But that, at least for the time being, doesn’t really matter. Now that I am aware that I am soon to die, I feel compelled to tell my story and record it for others, not merely for the very few who might be sufficiently gullible to believe it, but also for the more skeptical readers who, mistaking it for fiction, might be engaged and entertained by my life. It is, I realize, ironically more for the latter group than for the former that I am going to tell the truth, since anyone who would actually believe it, true as it truly is, would have to be insane. And, in my experience, there is little gratification in telling things to the insane—they only ever hear themselves. There is even less satisfaction in listening to the things that lunatics have to say—they only ever talk to themselves. I would rather that people presume that I am telling a tale than that I am crazy.

There have, of course, been at least moderately sane people who have, understandably but not rationally, believed far more unbelievable books than the one I aim to compose, preposterous tomes like the Torah, Gospels, and Koran, not to mention all the cockamamie scriptures of the Orient. Is it not substantially more mad to imagine that there could be some sort of life after death, as those religious texts propose, than it is to believe, as my autobiography shall testify, that life might be extended for a very, very long time before death?

Because few can be expected to believe that my book is nonfiction, it must, I realize all too well, seem to be a novel in order to be published and read. And so it will, of course, have to be artfully written. Thus I am contacting you, Mr. Siegel, for I am, alas, not much of a writer myself. After the completion of my last logbook in 1513, I did not write anything beyond the occasionally necessary love letter or business contract until the eighteenth century, when I composed several plays, including two about and starring myself, for the stage. These were, however, written in Spanish, largely plagiarized, and not, I must admit, of a very high literary quality. Although I have been speaking English for some two hundred years, ever since the period when British rule here made a familiarity with that language an asset, it is not my mother tongue. I do not, in all modesty, suppose that I can do justice to myself in your language.

Not only am I not much of a writer, I have never been much of reader either. Curiosity, however, has compelled me to study all that has been written about Juan Ponce de León as recommended to me by Miss Lilian Bell of the Eagle Springs branch of the Santa Almeja County Public Library. It was Miss Bell who gave me your name, Mr. Siegel. Over the years, she has dedicated herself to acquiring for her library’s folklore of Florida collection, among other things, all volumes written about Juan Ponce de León, fiction and nonfiction, juvenile and adult, alike.

Miss Bell informed me that you had written two books in which I am mentioned. Both were purchased by the library, and one of them has been checked out on more than one occasion. Your literary success, Mr. Siegel, seems to have been significant enough to allow me to surmise that you are in a position to get another book published, and yet not so substantial in terms of either fame or fortune that you, upon reading this letter, will not be tempted by the proposal that you collaborate with me on my memoirs. I shall make it well worth your while. In addition to a ten-thousand-dollar cash retainer for coming to Florida to work with me (plus reasonable expenses, of course), I am prepared to pay you one dollar per word for the finished manuscript. And, in order to motivate you to find a publisher for the work, you shall receive twenty percent of the royalties. That I am enclosing half of your retainer herewith should convince you of my sincerity. Consider this letter contractual.

Although I do not, as I have reiterated, believe that you will believe the stories I’m going to tell you, I do hope that you might allow yourself to believe that I believe them, or, at the very least, to write them down as though you do. It will be your job, as my ghostwriter, to edit my reminiscences into a text that is sufficiently entertaining to be published, sold, and read. It will be your responsibility, as a professional author, to make the hero of the book, Juan Ponce de León (b. 1465, Lebrija, Andalucia—d. 2005, Eagle Springs, Florida), convincingly real and as likable as I have always tried to be. I especially want our female readers to find me attractive. You will, of course, also be in charge of grammar, spelling, and punctuation, as well as of the preparation and submission of the final typescript for posthumous publication.

Having read the passages in your books alluding to me, I have faith in you, Mr. Siegel. Although I was a bit disappointed that you didn’t have more to say about me, it was encouraging to discover someone who imagined (albeit without the conviction of imagining that imagination might have been a medium for a revelation of a truth) that Juan Ponce de León might have actually discovered the Fountain of Youth and that he might still be alive. Little did you know that what you had invented was, in fact, a reality.

Since I do not have much time left, I am eager for you to get here as soon as possible. To this end I enclose herein a ticket for a flight leaving Honolulu for Jacksonville on the fourth of July. I hope that this gives you enough time for whatever you might need to do before we begin our work. It will not be difficult for you to get from Jacksonville to Eagle Springs by rental car. Signs along the highway will lead you to the Zodiac Motel where it will be convenient for you to reside while you collaborate with me. From there it will be easy to get directions and find your way here, to the Garden of Eden. I plan to see you on the morning of the sixth of July.

Yours very truly,

Juan Ponce de León

This is, I swear and have ample documentation to substantiate it, absolutely true. I really did receive the above outlandish letter in June 2005. It was handwritten in a barely legible small scrawl and ornately signed. The signature (below left) is, I was soon to discover, almost identical to that of a Juan Ponce de León on a 1513 petition to the Spanish Crown for a title to conquer, colonize, and Christianize lands sighted off the west coast of Florida (below right, as preserved in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain, and as reproduced in Leo Gaviota’s The True Story of Juan Ponce de León and the Fountain of Youth).

|  |

The letter had been folded around five of what appeared to be genuine one thousand-dollar bills, each engraved with the face of Grover Cleveland. Also enclosed was an Avis rental car voucher and a ticket for a confirmed business-class seat on an American Airlines flight from Honolulu to Jacksonville, via Denver, on July 4 (with a return on July 22). Affixed to the envelope, which had been addressed to my university office, were three twenty-two-cent commemorative stamps, each bearing the portrait of Juan Ponce de León.

It was hard to believe.

While there was, according to the long-distance information operator, no listing in Eagle Springs for either a Ponce de León (whether under a P, D, or an L) or a Garden of Eden (under either a G or an E), there was a number for the Zodiac Motel. And the man who answered the phone there assured me both that I did have a prepaid reservation for a room at the Zodiac and that the Garden of Eden really did exist: “But it closed down to the public a couple of months ago.”

I wouldn’t have taken the letter seriously, and I certainly wouldn’t have gone to Florida, if not for the cash. Yes, I confess, I did it mostly for the money. Not only was another five grand supposedly waiting for me there, there was also that promised dollar per word for the finished manuscript. I was confident that if, in fact, the character who wrote the letter really did want me to help him write the story of Ponce de León, I could come up with at least a hundred thousand words, about two hundred and fifty pages. This freelance summer job would bring in a lot more money than I earn in a year as a professor or that I have ever been paid for anything I’ve written.

Assuming as I did that the proposed book, given the absurdity of its premise, would never get published, I was hardly tempted to fantasize about royalties. But maybe, I reflected, heading east at thirty-five thousand feet above the Pacific Ocean, I could write a true story, a journalistic profile of “The Man Who Thought He Was Ponce de León.” The New Yorker might give me a few thousand for it, I imagined, at least if it were amusing enough in a New Yorker sort of way. While being rollickingly hilarious, I promised myself, it would also have something or other serious to say about the ways in which human beings struggle to come to terms with old age and the inevitability of death. Comic but poignant, silly but wise. If not the New Yorker, Esquire or Vanity Fair might bite. And if not them, I told myself as my plane began its descent into the Jacksonville International Airport, maybe I could convince an editor at Modern Maturity to shell out a couple hundred bucks for it.

But it wasn’t only the money that tempted me. The figure of Ponce de León had long been of some interest to me literarily. It was true, as noted in his letter, that I had written two books in which I referred to Ponce de León (Love and Other Games of Chance: A Novelty [New York: Viking Press (2003), 379–386], and Who Wrote the Book of Love? [Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2005), 57–71]). And, ironically, one of the very first things I ever wrote was about him. That was over fifty years ago when, in the fourth grade, I was constrained to learn about “Great Explorers of the New World.” Assigned to do a notebook on the Spanish conquistador who discovered Florida, I plagiarized my biography from the World Book Encyclopedia. It amused me to think that I’d be rewriting that school project after all these years.

Something else in the letter startled me—the man’s mention of his birthday on July 22. While I am aware that the mathematical probability is greater than 50 percent that, in a group of only twenty-three people, at least two will have the same birthday, I was, nevertheless, so intrigued by the happenstance that my own birthday falls on that very same day that, despite a more rational impulse to dismiss the coincidence as mere coincidence, I could not help but sense a kind of significance in it. It was almost as if it established, whether I liked it or not, some sort of magical connection between the writer of the letter and me.

The timing of the invitation was also convenient. It was summer vacation and I wasn’t making any progress on a novel I had been doggedly trying to write for several years. Not only that, the woman with whom I had lived for seven years had left me a month earlier. I was at a loss and lonely, and, in my case, loneliness always fosters restlessness.

And so, believe it or not, I went to Eagle Springs, Florida, checked into the Zodiac Motel, and then, after a long deep sleep, on the morning of July 6, I asked Mr. Wiseman, the motel’s owner and manager, for directions to Ponce de León’s Garden of Eden. I was given more information than I asked for: “Ponce de León! Oi! The guy is meshugeh if there ever was meshugeh. You think you know what meshugeh is? I’ll tell you what meshugeh is—it’s some shmuck who for more years than anyone can remember gets dressed up like a Spanish explorer and tells people that the Garden of Eden isn’t somewhere over in Israel like it’s supposed to be, but that it’s right here in Florida. Not only that, he pretends that he’s got the Fountain of Youth there and that, thanks to it, he’s over five hundred years old. That’s meshugeh. The Fountain of Youth! Oi! Oi! I’ll tell you what the Fountain of Youth is—it’s a kaneh.”

“What,” I had to ask, “is a kaneh?”

“Siegel! Are you a Jew or what?”

I confessed that, yes, I was Jewish.

“You call yourself a Jew and you don’t know from kaneh? A kaseer, a gluystiyah, a cristiyah—we’ve got more words for it in Yiddish than the Eskimos have for snow. It’s an enema, Siegel—yeah, a warm enema every night before you go to bed. I’m telling you, that’s how to stay young. That’s the only real fountain of youth. At least that’s what the Talmud says.”

In order to escape a very loquacious and overly familiar Mr. Wiseman, I insisted that I was late for my appointment with Ponce de León.

All along the roads that took me from the Zodiac Motel to the Garden of Eden that sultry Florida summer morning, there were, among expanses of cypress and cabbage palm, bright clusters of white and pink oleander, orange and purple bougainvillea, and the crimson blaze of flame tree blossoms. I saw a sign: “Ponce de Leon’s Fountain of Youth, Garden of Eden, and Museum of Florida History. 3 Miles Ahead. Children and Senior Citizens free.”

The man who claimed to have unearthed the legendary Fountain of Youth was waiting for me in the empty parking lot in front of the main gate to his Garden of Eden ludicrously dressed for the occasion in a conquistador costume: over a pale blue doublet, there was a high-collared padded plum houppelande, its funneled sleeves ballooned at the shoulders and scalloped at the cuffs; through the slashes in the dark blue puffed breeches, a satin lining that matched the color of his doublet had been decoratively pulled. The soft black leather of his gloves matched that of his silver-buckled knee boots. The crowning touch was a conquistador helmet dramatically festooned with crimson plumage. The uniform blackness of his beard suggested that it had been dyed. Only the dark Ray-Ban sunglasses and cigar were anachronistic. The costume made it difficult to guess his age. The sunglasses kept a distance between us. Given the heat and humidity of the Florida summer, the costume must have been uncomfortable to wear.

“I was expecting someone much younger.” Grandly saluting me with an antique Iberian short sword, he spoke in a noticeably rasping voice.

“And I was expecting someone far older, “ I joked, playing along with the performance. “It’s a pleasure, no less than it is an honor, to make the acquaintance of the illustrious Juan Ponce de León.”

Returning his sword to its filigreed scabbard with a theatrical flourish, he coughed. “Come along, Mr. Siegel. You must be eager to see the Fountain.” Mr. De Leon seemed anxious and in an unnecessary hurry. His nervousness, indeed his strangeness, made me uncomfortable. I was not looking forward to this. But I didn’t feel I had any choice but to follow him as led the way through the gate into a garden that seemed strangely bleak in contrast to the landscape leading up to the estate. There were, so far as I could see, no flowers in the Garden of Eden. There were dead leaves along the path on which we walked, and those that remained on the trees, bushes, and shrubs looked parched. The seemingly unnatural wilting of the vegetation suggested some sort of botanical blight.

Stopping abruptly, and turning to face me, Mr. De Leon asked if I was satisfied with what he was paying me: “Tell me the truth. Let us be honest with one another. If you need more money to do a good job, you must say so. Money doesn’t matter so much to me now, not so long as I am assured that, when I am dead, Isabel will have enough to live in comfort and at least modest luxury for the rest of her life. What’s important to me now, as I explained in my letter, is that you write my story, and that you do it well enough for people to want to read it and, in doing so, find some pleasure in it. You must do your very best, Mr. Siegel, better than you did on those other books you wrote. You’ve got to write this as though you really care, as if you believe it, or at least as though you almost believe it. Can you do that?”

I said I would try. What else could I say?

The tour of the grounds continued: “I do hope you realize, Mr. Siegel, that you are in the actual Garden of Eden. Yes, it’s true—the Paradise of Genesis. Although, as you shall learn, there are many mistakes, if not outright lies, in the first book of Moses, there is some truth in it as well. The biblical story of the Garden of Eden had, until I came here, always seemed to me a poetic allegory written in the past tense to describe a future paradise into which credulous Jews and Christians fantasized they might be admitted after death or after the coming, first or second, of a messiah. No reasonable person, I reasoned, would ever believe in the actual existence of waters that could prevent disease or arrest aging. Just as you naturally don’t believe in the Fountain now, neither did I for the first forty-eight years of my life. Actually, to be perfectly honest with you, I have from time to time over the years been a little uneasy about my belief in such a nonsensical notion. But, alas, Mr. Siegel, I have no choice but to believe in it, since I have, after all, been alive for five hundred and forty years. What could be more convincing than that?”

We came to a clearing in the withering shrubbery where there was a circular, white granite basin about fifteen feet in diameter and about five feet deep. “That’s it!” he exclaimed, “the Fountain of Life.” I would have imagined that Mr. De Leon would have constructed something much more ornate and spectacular as the featured item in his theme park.

“You’ll need to describe it in such a way that my readers can, in envisioning it, feel the mystery of it, the miraculousness. Bring the Fountain to life, Mr. Siegel.”

I didn’t know what, if I stuck to the truth, I would be able to write about it, except to note that it was rather dirty, and that, in the center of its empty tank there was a cracked column supporting four spigots, “one,” I was informed, “for each of the four rivers that flowed out of Eden.” And atop the column there was a tarnished bronze statue of a Spanish conquistador.

“Over the centuries,” my new employer commented, “I have used a variety of statuary to disguise the Fountain which, when I first discovered it, was a bubbling artesian spring and pond with no adornment. This particular statue of me has ornamented the Fountain since 1915 when I first opened the Garden of Eden and Museum of Florida History to the public.”

Mr. De Leon invited me to interrupt him if I had any questions. “You are, Mr. Siegel, perhaps wondering, ‘Where is the Tree of Knowledge with its forbidden fruit?’ That was perhaps the most frequently asked question by visitors to the Garden over the years. I’d explain to them that, contrary to Moses’s version of the story of creation, it was forbidden to eat any of the fruit of any tree in the Garden just as it was forbidden to pick any of the flowers. Since none of the plants in the Garden, being nourished by the waters of the Fountain of Life, were subject to aging or pestilence, none had the need nor, therefore, the capacity, to reproduce. All of the fruit in the Garden was seedless, all of the flowers without pollen. Once picked, the fruit and flowers would not be replenished. They would be gone forever. That was the terrible knowledge—the knowledge of gone-forever-ness—that the first inhabitants of the Garden were to gain when they ate the fruit from the trees of Paradise. Do you understand, Mr. Siegel?”

“Yes,” I said out of politeness.

“Do you have any questions?”

“No,” I dissembled.

He coughed to clear his throat and continued: “In any case, you’ll learn everything you need to know about the Garden of Eden and the Fountain of Life in the coming days. This is just an introduction. Come along. Let’s go to the house.”

The impressively grand whitewashed Spanish colonial plateresque building that turned out to be Mr. De Leon’s Museum of Florida History had been built, I was informed, of tabby, limestone, and coquina as a mission in the sixteenth century.

We entered a cobbled courtyard and I was directed to seat myself in one of two cane chairs beside a weather-warped wooden table in the shade of an arched loggia. Dark, dry vines barely adhered to its stone pillars. Walking away from me to the open doorway into the house, Mr. De Leon called out, “Isabel, mi redactor esta aqui.”

A stunningly pretty young woman appeared with a silver tray. She could not have been much older than twenty. Her immaculate white cotton dress was sleeveless, but her arms were covered by a grass-green shawl upon which bright blue and violet embroidered flowers were in full bloom. There were no cosmetics to enhance the resonant darkness of her alert eyes or the alluring ruddiness of her full lips. A lock of the black hair that had missed being tied into the bun at the nape of her neck played casually across her pale forehead, and a curl lay poised by each delicate ear, the lobes of which were adorned with glistening red gems. Setting the tray on the table, then standing behind my host, she remained silent and was not introduced. I noticed that her feet were bare.

On the tray there were two tumblers and a crystal pitcher of a dark refreshment in which floated ice cubes and slices of lime. “Rum,” Mr. De Leon exclaimed with a cough, “I invented it.” As if that had been a stage cue, the girl filled his glass and then mine. Also on the tray there was an antique cedar cigar humidor, a box of wooden matches, a ceramic bowl of popcorn, and a white envelope.

“Isabel,” he said, “¿Me puedes traer mi morfina por favor?”

After a moment of silence, during which he intently watched the girl walk back to the house, he handed me the envelope. It contained five one-thousand-dollar bills, the balance of my advance. It was hard to believe.

Opening the humidor, he casually claimed to have invented cigars: “Yes, I was the first person to distill rum and the first to roll tobacco in a tobacco leaf. You smoke, I hope, Mr. Siegel. Have one. I buy this brand not so much because they are particularly good, but because they’re named after me—Las Bacueas’ Ponce de León Puerto Rican Maduros. I like that. It assures me that there is some justice in the world. There are, as I am sure you know, those who insist that smoking is bad for you. But I’ve been smoking for almost five hundred years and, until very recently, I’ve been in perfect health. Smoking, I learned long ago from the natives of the Indies, is a salubrious act and a holy one as well.” Mr. De Leon was, I was somewhat startled to notice, inhaling the cigar smoke.

The girl returned with a small silver pillbox. After my host had washed down a tablet with an exuberant gulp of punch, she refilled his glass and returned to the house. He took another sip, pushed the bowl of popcorn toward me, coughed, and resumed: “Let’s get down to business, Mr. Siegel. We have a lot to do, and not much time. I will expect you here each morning, about an hour or so after sunrise. And we’ll work until sundown. You will listen, Mr. Siegel, to what I tell you each day, taking notes if you must, and then, each evening, I want you to write up a draft of whatever story I have told you that day. The next morning, I’ll go over what you have written, making comments to help you rewrite, correct, edit, polish, and whatever else it is that you writers do to come up with a finished book. I am, as I explained in my letter to you, no writer. Otherwise I would not have had to hire you. It’s my responsibility to give you a true account of my life, and it is your job to transform that into something literary, to fashion fine characters out of the people I tell you about, to give my life style, structure, and a plot, to spice it up with felicitous and evocative similes, metaphors, and other figures of speech. Your task is to write, mine is to remember. To remember … ”

With another gulp of rum punch he swallowed another pill, puffed on his cigar, coughed, and told me to help myself to the popcorn. And then, suddenly standing, he grandly announced the theme of the book: “Love. Yes, love. Love and time, love and age, love and death. Love true and false, glorious and foolish, tragic and comic. Yes, I’d like my autobiography to be a love story. It is not that I am so arrogant as to presume to be privy to any particular wisdom about that fantastic sentiment or its terrific powers any more now than I did when I fell in love for the first time some five hundred and twenty-five years ago in Andalucia. No, after all these years I still do not have any control over love or what it does to me, transporting me to the most joyous heights, plunging me into the most dismal depths, and dropping me willy-nilly and dumbfounded at all places in between. But how does one write about it? Being, or having been, in love seems to be an impediment to writing about it, since the true lover always feels that his feelings cannot be put into words. That, once again, is why I have hired you, so that you can do justice in the book to love and to the women with whom I have been in love, that you will make adorable heroines of them, and that with poetic diction you will make vivid the joy of the transport of cardarring them.”

He stopped, sighed, and nodded. “Cardar—that’s the verb I’d use if I were composing my story in my mother tongue, the Andalucian Ladino dialect of my childhood. I would write cardar—a loving, passionate and tender verb—literally: to card, curry, comb, and brush, to groom, clean, set aright, adorn, and restore, to coddle, soothe, please, serve, adore, to explore, enrapture, and beautify, not to mention to make love to and fuck of course—yes, all those things all at once. You must try to find some English equivalent, Mr. Siegel. If you do, I’ll pay you double for the word—two dollars each time you write it. And, I can assure you, it will be used often in my book.”

Mr. De Leon’s long-windedness and overblown grandiloquence might have irritated me if not for the five thousand dollars in the envelope in my hand. As I watched him down another glass of rum punch, I could not but be impressed by how well he held his liquor, not to mention his morphine. No sooner was the pitcher empty than, as though by some clairvoyance, the barefoot girl silently returned with a fresh one, only to immediately leave us alone again.

Topping up our glasses, he enthusiastically started up again, quite apparently enjoying the part he was playing. “I began my life as an actor,” he began. “‘Love,’ according to lines I first recited in a command performance of El Amor y el viejo for Their Majesties Fernando and Ysabel five hundred and thirty-three years ago, and yet remember as if it were yesterday, ‘keeps the young man young, and makes the old man lose his age.’ The old Castilian is sweet on the tongue: ‘El amor mançebo mantiene mucho en mançebez, e al viejo faz perder mucho la vejez.’” He coughed, inhaled cigar smoke, and coughed again. “If that were true, that love keeps us young—and, believe you me, it is not—I wouldn’t have needed the waters from the Fountain of Life to be alive today. I have been in love so many times during the past five hundred and forty years that I can hardly remember all the women who have meant the world to me. Have you ever attempted to do it, Mr. Siegel, to remember all the girls and women you’ve cardarred, each one of them, all of the nakedness you’ve gazed upon, all of the flesh you’ve touched and kissed and tasted, the hair you’ve smelled, the sighs and laughter you’ve heard?”

He didn’t pause to hear an answer. “I’ve been trying to do just that in preparation for our work together, Mr. Siegel. Of course the first one, no less than the last, is easy. I close my eyes and see her, the girl at Casa Susona, number one. Then there’s Celestina, my young bride, number two, Queen Ysabel, tres, Filomena, quatro, then the Taino girl, cinco, and then, right after her, there is, I am certain, someone missing. It vexes me that I can’t, for the life of me, remember her name, face, or figure, the color of her skin, eyes, or hair, not her nationality, not what language she spoke, nothing about her except that she was there. Number six is, I’m very sad to say, lost forever. Continuing to count across the centuries, among the scores of well-recollected women, wholly resurrected in memory, I see just parts of others, floating like jetsam from the wreckage of love on an unfathomable sea of time. Some are vaguely recalled only by a face, a neck, by arms or legs, hips or thighs, by an ear, or even just a fingertip. I remember a mole next to the nipple on a girl’s right breast. There was a matching one on her cheek. I remember women’s lips parting into smiles, others forming the blossom of a kiss, another mouth spraying water, and another breathing out smoke. I remember a certain woman’s eyes, sparkling aquamarine, and can still hear her whispering my name. I see the pearl buttons of a crimson tunic, a tiara of green parrot feathers, a woman’s drinking gourd and smoking pipe, a wine glass broken and the white linen around it reddened with the blood of the virgin grape. I remember cornucopia-shaped earrings of black glass, candlelight flickering on a thigh, and I hear cries of ‘por Dios, por Dios’ over the echoes of a Ladino song: ‘Del amor yo non savía.’ I see a tortoise-shell comb with a single strand of golden hair tangled in its teeth, the large coral beads of a rosary, a crucifix and dagger, and the illegible handwriting of a love letter.” He stopped, sighed, shook his head, relit his cigar, and then continued more slowly: “I’ll tell you all that I can remember about these women, Mr. Siegel. There is among them one with whom, I am certain, I was madly in love and quite intimate for some time, but about whom I remember nothing except her gravestone in St. Augustine’s Huguenot cemetery. Above the roses that I place there from time to time in my attempt at amorous recollection, I see words engraved in marble: ‘In Loving Memory. Rest in Peace. Anna Maria Ulm. 1785–1806.’ I know nothing about Anna Maria except her name, that she died when she was only twenty-one, and that I loved her.”

He paused to pour another drink, cough, and push the bowl of popcorn closer to me. And then he promised that he would do his very best to remember everything he could about his life as accurately as possible so that I could write a true story. “The truth is what we’re after. And we have no choice but to rely on memory for that truth. But, alas, in that dependence we must keep in mind that Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, bond-maiden of Venus Aphrodite and mother of the Muses, was known by the ancients to be a liar.”

Again he paused. “And without the sustenance of the waters of the Fountain, memory fails me more and more each day. We don’t have much time. Are you ready to begin your work, Mr. Siegel?”

Although uneasy about what I was getting myself into, I slipped the envelope into the breast pocket of my jacket, and claimed that, “yes,” I was.

“I must tell you, Mr. Siegel, that I’m worried about something,” Mr. De Leon divulged. “I am concerned that there might be, especially among the female readers of the chronicle of my love affairs, some who will consider me a cruel lover and not forgive me for breaking so many hearts over the years. I will rely on your literary acumen and rhetorical skills to convince them that, because of the Fountain, I had no choice but to end each liaison, and that I, no less than any of the women, suffered great sorrow each time I had to part with one of them. Let’s make it a point to note that I always ended my affairs as lovingly as possible. It’s your job, Mr. Siegel, to make the hero of my autobiography a wonderful lover, the kind of man that any woman would love to cardar and be cardarred by. Do you think you can do that?”

Again I said I’d do my best.

“Good,” he exclaimed with a smile of satisfaction. “Then we’ll get started on chapter one tomorrow morning. It’s the story of my childhood, boyhood, and youth in Spain.” Abruptly he stood, closed his eyes, and whispered, “Tomorrow.”

As I got into my car, he drew his sword from its scabbard to salute me good-bye. And, as I drove off, he, sword aloft, cried out, “¡Vale!”

After lunch in Eagle Springs at the Johnson Family Diner across the street from the town’s branch of the Santa Almeja County Public Library, with nothing better to do, I decided to introduce myself to the woman who had given my name to the man who had hired me as his ghostwriter. I asked her about him.

“Oh, I’ve known him for years,” a gleefully grinning little Miss Bell, obviously elderly but quite spry, told me. “He’s done so much to keep our history alive with that museum of his.” A permed blond wig, cat-eye glasses, and a bright patch of rouge on each cheek made the old librarian appear clownish, but in a sweet sort of way. She spoke of Mr. De Leon with a girlish affection apparent in her voice and smile. “I’m a history buff, you see—Florida history. And, as everyone knows, it all began with Ponce de León. I remember reading about him in grade school, when I was just a little girl in St. Augustine. He looked so dashing in the pictures in our history book, so swashbuckling in that plumed helmet of his, and he had those dreamy eyes and seemed so gentlemanly. And now that I’m older—you probably won’t believe it (nobody does) but I’ll be turning eighty this month—he’s still one of my favorite characters in history. I’ve read practically everything that’s been written about him. And no one, I’m sorry to say, has, in my opinion, really done justice to him yet. You know, it was I who suggested that he hire you to help him write the book.”

I thanked her and said that I was flattered.

“Well,” she continued with a persistent smile, “to be perfectly honest with you, I had advised him to contact Philip Roth, John Updike, Salmon Rushdie, and Dan Brown. It was so discouraging that not one of them answered his letters. That’s when I came up with your name. I’m so pleased that someone is going to help him.”

Miss Bell insisted on issuing me a temporary library card so that I could borrow books about the famed conquistador. She recommended Leo Gaviota’s The True Story of Juan Ponce de León and the Fountain of Youth and Douglas Peck’s Ponce de León and the Discovery of Florida: the Man, the Myth and the Truth. I also checked out Raoul Pipote’s The Rape of Virgin America and the University of Chicago Spanish-English Dictionary.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 1-15 of Love and the Incredibly Old Man: A Novel by Lee Siegel, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Lee Siegel

Love and the Incredibly Old Man: A Novel

©2008, 240 pages

Cloth $22.50 ISBN: 978-0-226-75705-6 (ISBN-10: 0-226-75705-6)For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Love and the Incredibly Old Man.

See also:

- An excerpt from Love in a Dead Language by Lee Siegel

- An excerpt from Who Wrote the Book of Love? by Lee Siegel

- All of our books by Lee Siegel

- Our catalog of fiction

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog