A chapter from

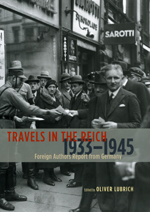

Travels in the Reich, 1933-45

Foreign Authors Report from Germany

Edited by Oliver Lubrich

Hitler Needs a Woman

by Martha Dodd

Martha Dodd had studied at the University of Chicago, had already worked for the Chicago Tribune, and had married for the first time when, in 1933, her father, the historian William Edward Dodd (1869–1940), was appointed United States ambassador in Berlin. She decided to accompany him to Germany. As a twenty-four-year-old, she arrived in Europe in the summer of 1933 with her parents and her brother. In 1939, after her return, and still before the beginning of World War II, she published her book on the four and a half years that she spent there. In Britain the book was entitled My Years in Germany, and in the United States, Through Embassy Eyes. After her father’s death, Dodd, with her brother Edward Dodd Jr. (1905–52), published Ambassador Dodd’s Diary (1941). Besides her political works, Dodd wrote some fiction, including a roman à clef entitled Sowing the Wind (1944/45) about the fighter pilot and armaments organizer Ernst Udet (1896–1941).

The following extracts from My Years in Germany narrate the arrival of the Dodd family in July 1933 (they travel to Berlin via Hamburg), a tour in August 1933 (to Southern Germany, Austria, and the Rhineland), and a meeting with Adolf Hitler. The young American was invited by Hitler’s foreign press chief, Ernst (known as “Putzi”) Hanfstaengl (1887– 1975), with the words, “Hitler needs a woman.” (Hanfstaengl, who had grown up in the United States, fled to England in 1937; during the war he was an adviser to the U.S. government.)

We had a slow sail up the Elbe and finally docked at Hamburg. Germany was here at last, with all of its profound meaning, the new future only guessed at and begun, to which my father gave all the idealism of his deeply emotional and disciplined life, with which he expected to co-operate and [from] which he hoped to benefit. I was moved by the eagerness, which he unconsciously expressed in returning in one of the highest positions our country can offer to its citizens, to the country he had so well loved, understood, and defended. For us, his children, here was a new adventure breaking into our middle youth, not sought after, not really fully appreciated; it was not an end or a beginning for us—or so we thought—but an episode occurring in the security of circumstance and love. It was not recklessness for us; it was our parents’ gift of an experience which could open or close or mean nothing in our lives. We greeted Germany with excited hearts, taking the future in our stride with the uncapturable nonchalance of youth, ready for anything or for nothing.

We must have presented one of the most amazing spectacles in the history of diplomatic arrivals, though, of course, we were completely unconscious of it at the time. My father had misread a telegram sent by the counsellor of the Embassy. He thought that the tickets to Berlin, the private car, etc., had all been arranged, so we didn’t bother about arranging for them on board, and in the confusion of disembarking forgot to get our necessary cards. Until the last moment he was busy with interviewers and newspapermen. One of the journalists was a correspondent of a Jewish newspaper in Hamburg. He wrote an article saying that my father had been sent over to solve the Jewish problem. Later we heard about it, and realized how badly garbled the account was. The German papers were very polite to us, but took the occasion to point out that this was the way of Jews.

My brother had planned to drive our Chevrolet to Berlin, but had done nothing about the red tape of getting it off the ship, with the permits and licences, and so on, that it involved.

The Counsellor, the adviser to the Ambassador and next in rank to him, a gentleman of the most extreme Protocol (we hadn’t yet heard this word) school, with grey-white hair and moustache which looked curled, elegant dress, gloves, stick and proper hat, a complexion of flaming hue, clipped, polite, and definitely condescending accent, was so horrified at our informality that his rage almost—not quite—transcended the bounds allowed by his rigid code of behaviour. We had no pretentious car, we had no chauffeur; valets, secretaries, and personal maids were ominously missing—in fact, we looked like simple ordinary human beings the like of which he had not permitted himself to mingle with for perhaps most of his adult life.

Finally, everything was put in order, my brother driving the modest car and the rest of us going by a regular train to Berlin (we should have at least taken the “Flying Hamburger,” the fastest and most expensive special). My father sat in one compartment talking over the political developments of Germany with the Counsellor, who was attempting in the most polished manner he could summon, to hint that my father was no longer a simple professor, but a great diplomat, and his habits and ways of life should be altered accordingly. But the honest and subtle, gentle and slightly nervous scholar was to remain as firm in his integrity of character as if there had been no change in his environment or position. I didn’t realize how futile all admonitions were, and I am sure my father was as supremely indifferent to them then as he was to be later when great pressure from all sources was applied to effect the desired transformation.

My mother and I were in another compartment, she uneasy and heavy of heart at the thought of the duties and change in life-patterns confronting her; and I sound asleep on her shoulder, both of us shrouded in expensive flowers.

The train stopped suddenly and I had just time enough to rub my eyes, jam on my hat and step onto the platform, a little dazed and very embarrassed. Before me was a large gathering of excited people; newspapermen crowding around us, and the ever-watchful Counsellor attempting to keep them away; Foreign Office representatives, other diplomats, and many Americans, come to look over the strange Ambassador and his family. The flashlights were a steady stream of blinding light and somehow or other I found myself grinning stupidly into the camera with bunches of orchids and other flowers up to my ears. My father took the newspapermen aside and gave them a prepared statement of greeting and we were hustled away.

I was put into a car with a young man who, I soon learned, was our Protocol secretary. I finally got the definition. He was pointing out the sights of Berlin to me. We drove around the Reichstag building, which he duly named. I exclaimed: “Oh, I thought it was burned down! It looks all right to me. Tell me what happened.” He leaned over to me, after several such natural but indiscreet questions, and said, “Shssh! Young lady, you must learn to be seen and not heard. You mustn’t say so much and ask so many questions. This isn’t America and you can’t say all the things you think.” I was astonished, but subdued for the time being. This was my first contact with the reality of Germany under a dictatorship and it took me a long time to take his advice seriously. Long habits of life are hard to change overnight.

We arrived at the Esplanade Hotel and were ushered into the Imperial suite. We gasped at its magnificence and also at what we thought the bill would be. Again the rooms were so filled with flowers that there was scarcely space to move in—orchids and rare scented lilies, flowers of all colours and descriptions. We had two huge high-ceilinged reception rooms lined with satin brocades, decorated with gilt and tapestried furniture and marble tables. Our welcoming friends finally left us to our own devices and my father went to bed with a book. Mother and I sat around, small and awed by the glamour of being the Ambassador’s family, receiving cards that began coming in and more baskets of flowers, wondering desperately how all this was to be paid for without mortgaging our souls. We did not know then that the hotel has special rates for visiting “potentates,” and had been even more considerate in our case. The Adlon hotel manager had wired us to accept a suite in his hotel free of charge, or at such a low rate that it seemed free, but Ambassadors had had the habit of residing at the Esplanade and we were not allowed to break the precedent.

My father was in magnificent humour at dinner-time. We all went down to the hotel dining-room to order the meal. My father was pouring out his German, teasing the waiters, and asking them questions—most undignified behaviour for an Ambassador. I never heard so many “Dankeschoens” and “Bitteschoens” in my life in one single evening, and it was my first introduction to the almost obsequious courtesy of German waiters. We had a good but heavy German dinner and I tasted my first German beer.

After we had finished, we decided to walk around a bit near the hotel before going to bed. We walked the length of the Sieges Allee lined on each side with rather ugly and pretentious statues of former rulers of Germany. My father would stop before each one and give us a short historical sketch of his time and character. He was in his element here as he knew German history almost by heart and if he missed out on something, he made a mental note for future study. I am sure this was one of the happiest evenings we spent in Germany. All of us were full of joy and peace. We liked Germany, and I was enchanted by the kindness and simplicity of the people, as far as I had seen them. The streets were dully lit, almost like a small American town late at night; there were no soldiers on the streets; everything was peaceful, romantic, strange, nostalgic. I felt the press had badly maligned the country and I wanted to proclaim the warmth and friendliness of the people, the soft summer night with its fragrance of trees and flowers, the serenity of the streets.

I was laid up in bed for the next few days with a bad cold. Sigrid Schultz came to see me. She is the correspondent for the Chicago Tribune and has been in Germany for over ten years. Small, a little pudgy, with blue eyes and an abundance of golden hair, she was very friendly and intelligent, with a mind alert if not always accurate, and a great news-hound. She had known the Germany of the past and she was sick at heart now. She told me many stories about the Nazis and their brutalities, the Secret Police before whom she was regularly summoned for the critical reports she wrote. I didn’t believe all her stories. I thought she was exaggerating and a bit hysterical, but I liked her personally and was interested to get a line on some of the people I was going to be associated with—diplomats and journalists.

I had a letter to the already quite famous American newspaperman H. R. Knickerbocker from Alexander Woollcott which I soon sent by post. He called up and asked me for a tea date. He was a small, slender man with red hair and warm, bright brown eyes, and a mobile mouth. We danced—which he does beautifully—and he asked me if I knew German or Germany, or anything about the Nazis. After revealing to him what must have seemed like appalling ignorance, he talked a bit about the Nazi leaders and soon shifted to other things. I wasn’t interested in politics or economics and was mainly concerned in getting the “feel” of the people. I was delighted by them and still remember my joy that afternoon at the Eden Hotel, watching their funny stiff dancing, listening to their incomprehensible and guttural tongue, and watching their simple gestures, natural behaviour and childlike eagerness for life.

During this first month we were receiving calls from Germans and Americans, listening to all sorts of points of view to which I did not respond very deeply, being so utterly absorbed in understanding the temper and heart of a foreign people. Unconsciously, I began to compare them, as we went around to reasonable or cheap restaurants—not at all in the accepted fashion of diplomats—to the French. The Germans seemed much more genuine and honest, even in the merchant class. I was pleased that they did not try to cheat us when it was so clear that we were foreigners, that they were very solemn and sympathetic when we first started to speak our pathetic German. They weren’t thieves, they weren’t selfish, they weren’t impatient or cold and hard; qualities I began to find stood out in my mind as characteristic of the French. We joked a lot, and I think only my father took seriously the warnings that the servants were apt to be spies and that dictaphones and eavesdroppers were encircling us.

Among the various newspapermen I met at this time was Quentin Reynolds, the Hearst correspondent. He was a big hulk of a man, with curly hair, humorous eyes and a broad beaming face. Sharp and tough and unsentimental, I thought him an excellent newspaperman. He had been in Germany a few months and was picking up the language rapidly. He knew intimately such legendary figures as Ernst (“Putzi”) Hanfstaengl, and arranged for us to meet at a party given by an English journalist. It was a lavish and fairly drunken affair with an interesting mixture of Germans and foreigners. Putzi came in late in a sensational manner, a huge man in height and build, towering over everyone present. His face was heavy and dark, rather underslung and concave in shape. He had a soft, ingratiating manner, a beautiful voice which he used with conscious artistry, sometimes whispering low and soft, the next minute bellowing and shattering the room. He was supposed to be the artist among the Nazis, erratic and interesting, the personal clown and musician to Hitler himself. He usually dominated every group he was in by the commanding quality of his powerful physical presence, or by the tirelessness of his indomitable energy and never-ending talk. He could exhaust anyone and, from sheer perseverance, out-shout or outwhisper the strongest man in Berlin. I was fascinated and intrigued by my first contact with a Nazi high up in official circles, so blatantly proclaiming his charm and talent. Bavarian and American blood produced this strange phenomenon. He could never have been a Prussian and he was proud of it.

First Impressions of Germany

Quentin Reynolds suggested to my brother and me that we take our Chevrolet and make a trip with him through Southern Germany and Austria. With a little persuasion my parents thought it would be a good way for us to study Germany.

So the three of us set out in August, a little over a month after our arrival, and made for the south. It was an exciting trip and the lack of German gave us some amusing moments in asking directions and ordering food. We stopped off at Wittenberg and saw the ninety-seven theses of Luther nailed, in bronze, on the church door, and went on to Leipzig, my father’s old university town. There, of course, we drank many steins of beer in the old Auerbach Keller in honour of the meeting of Faust and Mephistopheles. All along the roads and in the towns we saw the Nazi banner, with the red background, the white circle in the centre emblazoned with the mystic crooked cross. Driving in and out of towns we saw large banners strung across the road on which I recognized the word “Jude.” We realized this was anti-Semitic propaganda, but we didn’t—at least I didn’t—take it too seriously. Furthermore, I couldn’t read the German well enough to have a full understanding of the words, and I must confess the Nazi spirit of intolerance had not yet dawned on me in its complete significance.

Enthusiasm was wild—or so it seemed on the surface. When people looked at our car and saw the low number, they “Heiled” energetically, probably thinking we were an official family from the great capital. We saw a lot of marching men, in brown uniforms, singing and shouting and waving their flags. These were the now-famous Brown-Shirt Storm Troopers, through whose loyalty and terroristic methods Hitler seized power. The excitement of the people was contagious, and I “Heiled” as vigorously as any Nazi. Quentin and my brother frowned on me and made sarcastic remarks about my adolescence, but I was enjoying everything fully and it was difficult for me to restrain my natural sympathy for the Germans. I felt like a child, ebullient and careless, the intoxication of the new regime working like wine in me.

We stopped in Nürnberg for the night and, after having reserved attractive and cheap rooms, went out to roam over the town and get a bite to eat. As we were coming out of the hotel we saw a crowd gathering and gesticulating in the middle of the street. We stopped to find out what it was all about. There was a street-car in the centre of the road from which a young girl was being brutally pushed and shoved. We moved closer and saw the tragic and tortured face, the colour of diluted absinthe. She looked ghastly. Her head had been shaved clean of hair and she was wearing a placard across her breast. We followed her for a moment, watching the crowd insult and jibe and drive her. Quentin and my brother asked several people around us, what was the matter. We understood from their German that she was a Gentile who had been consorting with a Jew. The placard said: “I Have Offered Myself to a Jew.” I wanted to follow but my two companions were so repelled that they pulled me away. Quentin, I remember, unfeeling and hard-boiled as I thought he was, was so shaken by the whole scene that he said the only thing he could do was to get drunk, to forget it—which we all did on red champagne.

I felt nervous and cold, the mood of exhilaration vanished completely. I tried in a self-conscious way to justify the action of the Nazis, to insist that we should not condemn without knowing the whole story. But here was something that darkened my picture of a happy, carefree Germany. The ugly, bared brutality I thought would make only a superficial impression on me, but as time went on I thought more and more of the pitiful, broken creature, a victim of mass-insanity.

I urged Quentin not to write up the story. It would make a sensation because of our presence—the new Ambassador’s children. It was an isolated case. It was not really important, would create a bad impression, did not reveal actually what was going on in Germany, overshadowed the constructive work they were doing. I presented many foolish and contradictory arguments. He decided not to cable the story, but only because he said there had been so many atrocity stories lately that people were no longer interested in them; he would write it as a news-story when he returned. But when we got back to Berlin we discovered that another journalist had been in the town and had cabled the story immediately and that all the press everywhere had headlined it, and also commented on our being witnesses.

The next morning we headed south. My brother was trying to make Innsbruck to see a girl of his, so we sped through the country, stopping only long enough to get food and gasoline and have a drink or two. We drove to Bayreuth but we were too late for the opera so we only visited the opera-house for a moment and in the dark, and hurried on. Quentin took the wheel and we sped over mountains and hills and curves at a mad rate. Little south-German villages, beautiful solid white houses, flying by us on each side, looking ancient and ghostly and lonely as our headlights flashed over them for a second.

We finally got to Innsbruck, tired but miraculously alive, and soon went to bed. The next morning we looked around the town, one of the most beautiful spots in Europe. The scenery was magnificent and the people even more helpful and friendly than in other places—but, of course, it was not a Nazi town. [ . . . ]

We finally left Austria, with its grace and charm, softened careless speech, and went back to Germany, having only once received a Nazi salute as we were nearing the border. It was strange returning to Germany, the music and poetry we had been so full of seemed ominously absent. Again as we travelled north along the Rhine, we saw the flags and the marching men, the brown uniforms, the martial character of the nation beginning to impress itself. It didn’t seem as spontaneous in the Rhine country as in other parts and we were wondering as we drove along and tried to talk with the people, what reservations they were making. The Nazi emblems and symbolism seemed grafted on to this dark and vivacious people.

We stared, in the usual fashion of tourists, at the famous Lorelei Rock, dark and mysterious above the murky, slow-moving Rhine, stared in wonder at the ancient ruins, evocative and beautiful, isolated and majestic on the tops of wild mountains. We drank more than the usual portion of golden wine, like liquid sun caught in a glass. Finally, the time was up and we drove quickly towards Berlin, passing through the dark and deeply-wooded Harz, memories of the myths, legends, and fairy stories in our minds.

Back in Berlin again, feeling already as if it were home, and rested and fresh from the exhilaration of travel, we began to open our eyes to things about us, to contrast the Germany we had been travelling through with the Prussia we resided in.

Quentin called to say that his home office was annoyed that he had missed the story in Nürnberg. The Foreign Office called at our home, seemingly very much perturbed; regretted and apologized for the incident of isolated brutality which they assured me was rare and would be punished.

Hanfstaengl had been calling up and wanting to arrange for me to meet Hitler. Hanfstaengl spluttered and ranted grandiosely: “Hitler needs a woman. Hitler should have an American woman—a lovely woman could change the whole destiny of Europe. Martha, you are the woman!”

As a matter of fact, though this sounded like inflated horse play as did most of Putzi’s schemes, I am convinced he knew the violence and danger of Hitler’s personality and ambitions, and deceived himself, at least partially, and wished frantically that something could be done about it.

So, for some months, when he was not telling assembled guests that he would like to throw a hand-grenade into the house of the little doctor which was below his apartment, he was trying to find a woman for Hitler. However, I was quite satisfied by the role so generously passed on to me and rather excited by the opportunity that presented itself, to meet this strange leader of men. In fact, I was still at this time, though growing critical of the men around Hitler, their methods and perhaps the system itself, convinced that Hitler was a glamorous and brilliant personality, who must have great power and charm. I looked forward to the meeting Putzi told me he had arranged.

Since I was appointed to change the history of Europe, I decided to dress in my most demure and intriguing best—which always appeals to the Germans: they want their women to be seen and not heard, and then seen only as appendages of the splendid male they accompany—with a veil and a flower and a pair of very cold hands. We went to the Kaiserhof and met the young Polish singer, Jan Kiepura. The three of us sat talking and drinking tea for a time. Hitler came in with several men, bodyguards and his well-loved chauffeur (who was given almost a State funeral when he died recently). He sat down unostentatiously at the table next to us. After a few minutes Jan Kiepura was taken over to Hitler to talk music to him, and then Putzi left me for a moment, leaned over the Leader’s ear, and returned in a great state of nervous agitation. He had consented to be introduced to me. I went over and remained standing as he stood up and took my hand. He kissed it very politely and murmured a few words. I knew very little German, as I have indicated, at the time, so I didn’t linger long. I shook hands again and he kissed my hand again, and I went back to the adjoining table with Putzi and stayed for some time listening to the conversation of the two music-lovers and receiving curious, embarrassed stares from time to time from the leader.

This first glance left me with a picture of a weak, soft face with pouches under the eyes, full lips and very little bony facial structure. The moustache didn’t seem as ridiculous as it appeared in pictures—in fact, I scarcely noticed it; but I imagine that is because I was pretty well conditioned to such things by that time. As has often been said, Hitler’s eyes were startling and unforgettable—they seemed pale blue in colour, were intense, unwavering, hypnotic.

Certainly the eyes were his only distinctive feature. They could contain fury and fanaticism and cruelty; they could be mystic and tearful and challenging. This particular afternoon he was excessively gentle and modest in his manners. Unobtrusive, communicative, informal, he had a certain quiet charm, almost a tenderness of speech and glance. He talked soberly to Kiepura and seemed very interested and absorbed in meeting both of us. The curious embarrassment he showed in meeting me, his somewhat apologetic, nervous manner, my father tells me—and other diplomats as well—are always present when he meets the diplomatic corps en masse. This self-consciousness has created in him a shyness and distaste for meeting people above him in station or wealth. As time went on, Hitler’s face and bearing changed noticeably—he began to look and walk more and more like Mussolini. But this peculiar shy strain of character has to this day remained.

When I left the Kaiserhof with the ecstatic and towering jitterbug Putzi, I could lend only half an ear to his extravagant, senseless talk. I was thinking of the meeting with Hitler. It was hard to believe that this man was one of the most powerful men in Europe—even at this time, other nations were afraid of him and his growing “New Germany.” He seemed modest, middle class, rather dull and self-conscious—yet with this strange tenderness and appealing helplessness. Only in the mad burning eyes could one see the terrible future of Germany.

When I came home to dinner I described my impression of the “great leader” to my father. He, of course, was greatly amused at my impressionableness, but admitted with indifference that Hitler was not an unattractive man personally. He teased me and urged me not to wash my hands for weeks thereafter—I would certainly want to retain as long as was hygienically possible, the benediction of Hitler’s kiss. He said I should remember the exact spot and perhaps, if I must wash, could wash carefully round it. I was a little angry and peeved at his irony, but tried to be a good sport about it.

That night I had a small party at my house. Young Stresemann, whom I had met shortly after I arrived in Germany, the musically talented eldest son of the famous statesman, came, as did the Frenchman of whom I was very fond despite my conflict with his political views, and a man named Hans Thomsen, who was in the Kanzlei of the Fuehrer and supposed to be very close to him. Of Danish descent, and with the suavest and gentlest manner I had met among Germans, he was both charming and interesting to me. As time went on he frequented our house with his friend, Miss Rangabe, with clock-like regularity—and never missed a party of mine or my parents for a year to two. He seemed to be an ardent Nazi, approaching the whole problem, I thought, from a reserved and intellectual point of view. There was very little hysteria about him; I thought, as many did who met him, that he might have private and personal reservations, but that on the whole he was one of the best representatives they could have. He was extremely popular with the diplomatic corps as a whole, and his soft, restrained manner made more friends for his party than almost any man in our circle. Diplomats, including my father, would take him aside and consult fairly confidentially with him, describing what they considered were terrible mistakes in policy, internal and foreign; and would make friends with the blond-haired, soft-spoken, subtle and mature diplomat, so that Thomsen enjoyed an “inside” track with the corps, freely and frankly offered, and perhaps as freely made use of by the Germans.

Hanfstaengl came late, as usual, that night and when he arrived was in jubilant spirits. He carried on an animated conversation with young Stresemann about music, and both agreed that Schubert’s Unfinished was one of the most glorious bits of music ever written. Judge a German by his musical tastes and you have a pretty definite clue to his intellectual position in general. I went to the victrola and put on the Horst Wessel Lied which someone had given me. It is fairly good marching music and when sung by large throngs can be quite stirring—and is the double National Anthem of the Germans. Hanfstaengl was enjoying it, not entirely without humour. Thomsen suddenly got up, went to the victrola, and turned it off abruptly. There was a strange tenseness on his face. I asked innocently why he didn’t like it. He answered, very sternly: “That is not the sort of music to be played for mixed gatherings and in a flippant manner. I won’t have you play our anthem, with its significance, at a social party.” I was startled and annoyed.

Hanfstaengl gave Thomsen a vivid look of amusement tinged with contempt and shrugged his shoulders. He said later: “Yes, there are some people like that among us. People who have blind spots and are humourless—one must be careful not to offend their sensitive souls.”

Somehow the evening was spoiled. The guests kept up their lively conversation and discussion, but most of them, not being fanatic Nazis and some definitely anti-Nazi, now knew that Thomsen was not a gay, intelligent, lighthearted, or reasonable friend, but a passionate partisan. They reacted to this in their individual ways and they were all a little self-conscious in his presence.

Unconsciously this may have been the turning-point of my reactions of a simple and more social nature to Nazi dictatorship. Accustomed all my life to the free exchange of views, the atmosphere of this evening shocked me and struck me as a sort of violation of the decencies of human relationship.

![]()

Copyright notice: A chapter from Travels in the Reich, 1933-1945 by Oliver Lubrich, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2010 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Edited by Oliver Lubrich

Travels in the Reich, 1933-1945: Foreign Authors Report from Germany

©2010, 336 pages

Cloth $30.00 ISBN: 9780226496290

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Travels in the Reich, 1933-1945.

See also:

- Our catalog of history titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog