An excerpt from

Patty’s Got a Gun

Patricia Hearst in 1970s America

William Graebner

Introduction

Patty Hearst’s life changed abruptly at 9 p.m., February 4, 1974, when her fiancé, philosophy graduate student Steven Weed, opened the front door of their Berkeley, California, apartment. Two armed men and a woman, members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, pushed their way in. “Bitch,” one of them said to Patty, “better be quiet, or we’ll blow your head off.” In less than three minutes, Patty, wearing only a blue bathrobe, had been gagged, blindfolded, and, her hands bound, dragged through the living room, struck in the face with a rifle butt, and forced into the trunk of a car. She had been kidnapped.

For more than three months following her abduction, Patty Hearst—the nineteen-year-old daughter of Randolph Hearst, son of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst and chairman of the board of directors of the Hearst Corporation—held the attention of the American media, competing for front-page space with the final stages of the Watergate scandal. The SLA released a series of recordings, containing demands and eventually statements by Patty indicating that she now embraced the group’s revolutionary agenda. In April, ten weeks after her abduction, she was photographed taking part in the armed robbery of a San Francisco bank. In May the SLA resurfaced in Los Angeles, where six of its members died in a fire following a police standoff. Then Patty and her surviving captors—or comrades—disappeared.

Arrested in San Francisco in September 1975, after more than a year on the lam, Patty again found herself in the spotlight. In January 1976 journalists jammed the U.S. District Court for the opening of her trial for the bank robbery, and her subsequent conviction was, of course, front-page news and the subject of editorial comment in newspapers across the country. Between February 1974 and March 1976, Patty Hearst was on the cover of Newsweek seven times.

Given Patty’s position as an “heiress” (the noun most frequently used to describe her), her kidnappers’ flair for publicity, and some of the bizarre things she did while with the SLA, it was inevitable that she would achieve celebrity status. But one facet of her fame was odd, even discomfiting: Patty was dull. Not dull to a fault, and not dull as in stupid. Just ordinary. Short, moderately attractive, living a “quiet life” of middle-class domesticity in a modest, five-room duplex in a building called “the Townhouse” on Berkeley’s Benvenue Avenue, engaged to be married at nineteen. Weed described their lives as “pleasantly routinized with our studies, movies on weekends, laundromat and grocery runs.” In summer 1972, at age sixteen, Patty had dutifully set off on a cultural tour of Greece and Italy, only to abandon it halfway through. “I hate to admit it,” she wrote Steven, “but I’m terribly homesick.… Venice is nice, but smelly. Rome is really beautiful, but I’m afraid to go out of the hotel alone—men don’t just whistle here, they run at you and try to grab you! I am even getting tired of looking at all the uncircumcised penises on the statues around here!… I may never open another art book again.” “The only thing in the world she wanted then,” said Weed, “was to have two kids, a collie, and a station wagon.”

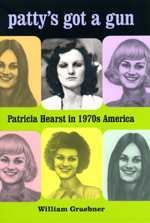

Patricia Hearst with beret and sawed-off M-1 rifle, April 1974. (Color version of b/w photo in the book.) |

|

The problem of the mutable self is an old one, a product of modernity’s disruption of a premodern round of life built on community, tradition, and bedrock expectations about one’s life and what one could expect from it. The erosion of those comfortable arrangements brought distress and consternation but also opportunity, perhaps best captured in the nineteenth-century celebration of the “self-made man.” A century later, the social upheavals of the 1960s and early 1970s opened up an even greater range of possibilities, all of which were available to an unsuspecting Patty Hearst. In Berkeley, a city symbolic of personal and political change, being an urban guerrilla was a lifestyle option. Race, gender, class, age, sexuality, sexual preference, political commitment, personal appearance, lifestyle—by 1970 all had been unmoored from limits and boundaries and transformed into a smorgasboard of choices. The idea of the “loosening of the self” not only underpinned specific 1970s enthusiasms—for jogging, natural foods, voluntary communities, and the geodesic dome—but also authorized the active search for a new, more “authentic” self, indeed, the very idea of choice. “To be loose,” writes sociologist Sam Binkley, “was to choose oneself.” By the mid-1970s, the San Francisco Bay Area was home to new movements and organizations offering a variety of nonmainstream ways to “choose oneself”: the Peoples Temple, a religious organization that would become infamous for the 1978 mass suicide of its members in Jonestown, Guyana; a powerful lesbian and gay community that in 1977 elected the city’s first openly gay supervisor, Harvey Milk; Redstockings West and other radical feminist groups; and radical, New Left splinter groups such as Venceremos—and the SLA.

During her trial, images of Patty as an active agent in the creation of her new self came up against her courtroom demeanor, which was passive in the extreme. Anyone’s Daughter, journalist Shana Alexander’s account of the trial, regularly comments on Patty’s pasty, gray, “fish’s belly” complexion, notes her “copybook plain” handwriting (“as controlled and uninflected as her voice”), and summarizes the court-ordered report on Patty’s mental state as describing “a person of åflat affect’ and shallow mind,” unusually “concerned with proper hostesslike behavior,” a person “living only in the moment, without past or future.” The word “zombie” appears frequently in Alexander’s account: Patty is “looking totally zombielike once more”; Wendy Yoshimura, her roommate during her year as a fugitive, “saw her as almost a zombie: depressed, withdrawn, subservient”; Dr. Margaret Thaler Singer, one of several court-appointed psychiatrists, labeled the Patty Hearst she observed in October 1975 as “a low-IQ, low-affect zombie”; and a juror later described his confusion in trying to square Patty’s dynamic public image with her colorless courtroom visage, “one of them animated, one a zombie.” “At the time,” this juror recalled, “I couldn’t figure out what the hell was going on.”

Nor could most Americans. Who was this young woman whose colorless life had been punctuated with nineteen months as captive, bank robber, gunfighter, radical revolutionary, feminist, and fugitive? Was there something extraordinary in Patty’s background or makeup that could explain the variety of roles she had taken on in so short a time? Or was this protean Patty a sort of mirror image of the ordinary Patty? And, if that were true, were all ordinary people vulnerable, or open, to such dramatic transformations?

A darker, more threatening explanation for Patty’s conduct surfaced frequently during the trial, although, in the end, it did not carry the day. Perhaps the SLA’s treatment of Patty—the violent kidnapping, the sexual abuse, the constant threats, the program of indoctrination—had changed something inside her, made her compliant, willing to do anything. Reduced to this state, she resembled others who had been “broken” by their captors and made to do and say things contrary to conscience and character: pilots captured during the Korean War, concentration camp prisoners, and Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty, a Hungarian prelate who in 1948 penned a “confession” after thirty-nine days of abuse in a Communist prison. In this scenario, Patty hadn’t chosen anything, except, perhaps, to stay alive; rather, she was the helpless victim of a powerful new system of mental and physical manipulation.

Was Patty a victim, of duress or fear or what the defense labeled “coercive persuasion,” or had she taken up with the SLA willingly, decided to be a different person, chosen a new life? Did Patty’s engagement with the SLA have a historical or social cause (the “sixties” and growing “permissiveness” were among the favorites), or was her interior life—that is, her “free will”—sufficient to explain her conduct? If Patty had in some sense been taken over, if she had been brainwashed, turned into a zombie, converted under duress, or otherwise deprived of free will and full consciousness, were other, ordinary Americans, regardless of race, class, gender, and circumstance, just as vulnerable? Should they understand themselves, deep down, as potential victims or as free agents?

At one level these questions were about Patty, about her personality, her identity, and her social being. At another, more fundamental level, they probed the qualities and dimensions of what social scientists called, in the 1950s, the “American character” and, in the 1970s, “human nature.” They were also, in the broadest sense, political questions, questions asked of Patty Hearst concerning what had happened to her, but also pertinent to a variety of issues that lay just beneath the surface (and sometimes breached the surface) of everyday affairs—among them the meaning of the 1960s, standards of criminal responsibility, the role of women, and the idea of the welfare state.

These questions had deep resonance for a society caught in a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate climate of malaise, midway between the liberal zeitgeist of the 1960s and the emerging conservatism of the 1980s, between a culture that valued the endurance of the survivor and had compassion for the victim and one that longed for the transcendence of the hero. Patty’s ordeal received the attention it did not only because her story was unique and fascinating but because, at the moment of her trial, the most basic issues affecting her guilt or innocence, issues of philosophy and ideology, were unresolved. Had Patty been tried in 1965, she would surely have been acquitted, judged to be nothing more, and nothing less, than the unfortunate victim of kidnapping, rape, and physical and mental torture. Had she been tried in 1985, she would surely have been convicted, steamrolled by the Reagan revolution, judged to be just another person who had failed to take personal responsibility for her acts. The moment of her conviction, in March 1976, was somewhere in between, participating at once in a culture of the victim, grounded in experience and deeply felt, and an incipient culture of personal responsibility. Through most of the trial, attorney F. Lee Bailey presented Patty as victim, gambling that the past would hold, that the future would take its time in arriving. He was wrong.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 1–8 of Patty’s Got a Gun: Patricia Hearst in 1970s America by William Graebner, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

William Graebner

Patty’s Got a Gun: Patricia Hearst in 1970s America

©2008, 228 pages, 16 halftones

Cloth $20.00 ISBN: 9780226305226

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Patty’s Got a Gun.

See also:

- Our catalog of American studies titles

- Our catalog of history titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog