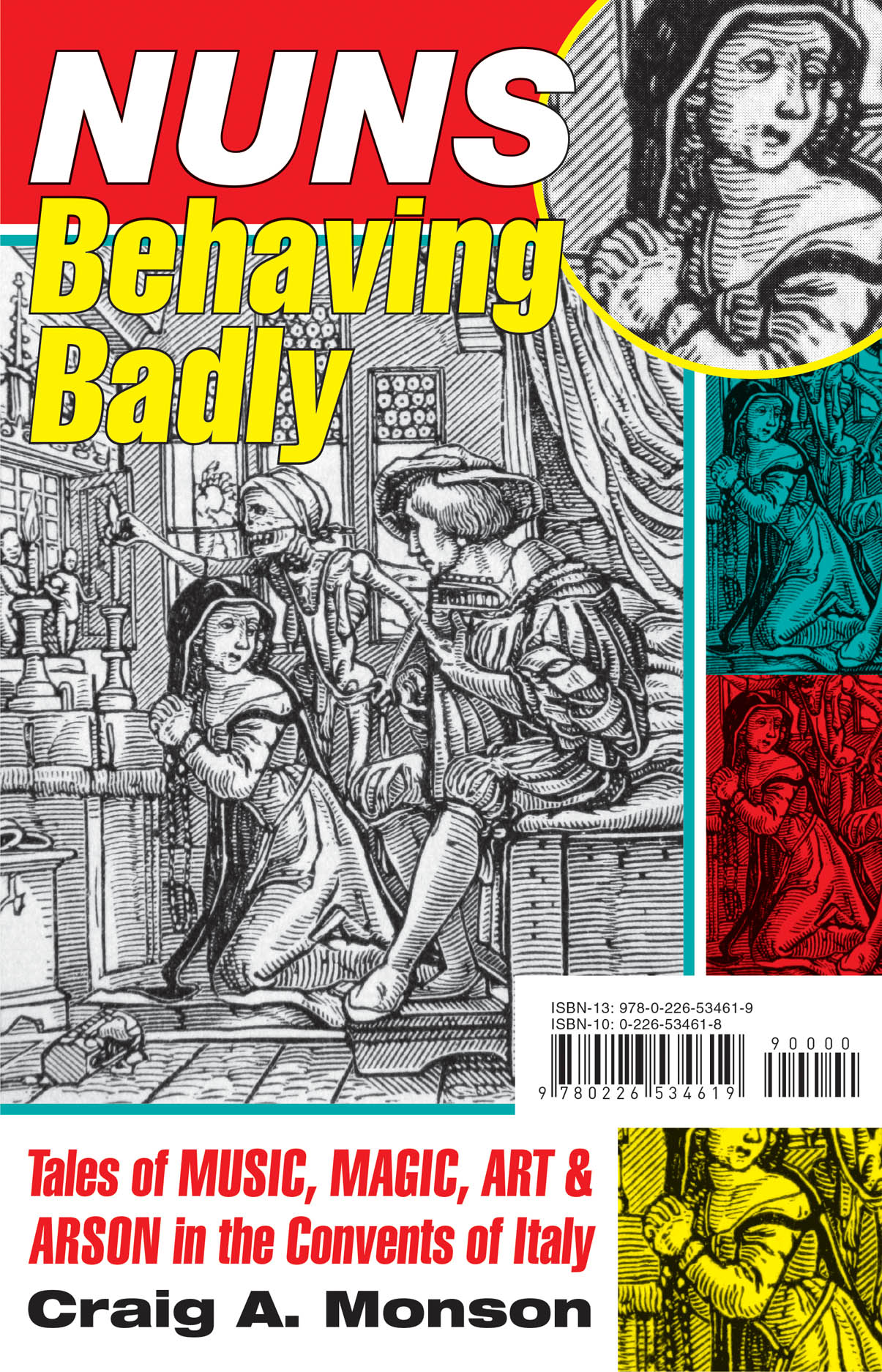

An excerpt from

Nuns Behaving Badly

Tales of Music, Magic, Art, and Arson in the Convents of Italy

Craig A. Monson

PROLOGUE

Topo d’Archivio

I became a topo d’archivio (an archive mouse—or rat) by accident.

In 1986 I returned to Florence after a twenty-year absence. In the hodgepodge collections of the Museo Bardini, off the well-beaten tourist track, I happened upon a Renaissance music manuscript. Lavishly bound, elegantly hand copied, as thick as the phone book of some midwestern city, it looked significant but forgotten. I recognized an academic article waiting to be written, so I returned the following summer for a closer look.

Dusting off a few tools from the musicological toolbox (a bit rusty by then, their cutting edges dull), I studied watermarks on the paper, the musical notation, the pieces it contained, the style of the tooled and gilded leather binding, a coat of arms on the front, and an inscription on the back:

.s.

.lena.

malve

ci

a.

These clues led not to Florence but to Bologna, and to Sister Elena Malvezzi at the convent of Sant’Agnese. Suor Elena had taken her vows there in the 1520s and had died, as prioress or subprioress, in 1563.

This was a surprise, because the manuscript chiefly contained French chansons and Italian madrigals. Now, in 1986 I didn’t know much about nuns, but I certainly didn’t expect them to be singing secular songs of this sort. I especially didn’t think they’d sing one that began:

Vu ch’ave quella cosetta

Che dilletta e piase tanto

Ah lasse che una man ve metta

Sotto la sottana e[’]l vostro manto.

[You who’ve got that little trinket,

So delightful and so pleasing,

Might I take my hand and sink it

Neath petticoat and cassock, squeezing.]

Despite my brief acquaintance at this point, sixteenth-century convent music and musicians looked a lot more interesting than their twentieth-century musical equivalents—Soeur Sourire (the singing nun of the 1960s) or Maria from The Sound of Music. Deloris Van Cartier (Whoopi Goldberg’s character) from Sister Act would have seemed quite another matter, but that film wouldn’t be released for another five years. Why did Renaissance nuns perform such elaborate music whereas their counterparts in modern times lead such seemingly bland lives? In the 1980s most musicologists associated nuns with chant, if they thought about nuns at all. What were these sisters doing singing this music? I turned my back on Elizabethan England, and on “note-centered” research, and became the topo d’archivio this subject required.

My discoveries confirmed what the Malvezzi manuscript had suggested. Convent singing was a contested issue. It provoked delight and fascination (from some—but not all—nun musicians and from their audiences), but also anxiety and conflict (from the church hierarchy). Initial research in Florence and Bologna revealed that convent music required even more careful control by the Catholic bureaucracy than other aspects of its performers’ cloistered lives.

So a chief place to continue searching for nuns’ music would have to be the Vatican, the center of that bureaucracy, and especially the records of the Sacred Congregation of Bishops and Regulars. This Sacred Congregation, consisting of various cardinals, had been created in 1572 to oversee every facet of monastic discipline throughout the Catholic world. Because nuns’ music of the sixteenth century to the eighteenth remained a “problem,” the Congregation’s archive should contain complaints, requests, judgments, and decrees about music.

Most such complaints and queries came from a local bishop or from his second-in-command, the diocesan vicar-general, acting in his name. In large dioceses, a specially deputized vicar of nuns (another step down in the priestly pecking order) might contact the Congregation. Sometimes it was the nuns themselves who lodged initial objections or tendered requests, though they frequently went right to the top, naively assuming that the pope himself would take an interest in their concerns. Their petitions also landed in the pile at the Bishops and Regulars. Whoever initiated the conversation, from that point on the nuns were commonly left out of subsequent dialogues, which involved prelates from their dioceses and other prelates in Rome. Much of the time the women religious who were the subject of investigation had little direct voice in discussions and deliberations about them.

Of course, one would expect any such deliberations about convent music to be buried amid hundreds of thousands of other documents treating diverse monastic matters, all tied up in some two thousand buste (“envelopes”—though in this case “bales” would be more accurate). Organized year by year and by months within each year, and anywhere from six to sixteen inches thick, these buste sit on block after block of shelving in the Vatican Secret Archive.

I made my way to Rome in 1989, and, after a friendly nod from a Swiss Guard at the gate, I passed through the wall into Vatican City. Diffidently proffering credentials and an elaborately signed and sealed American university letter of introduction, I negotiated the bureaucratic hurdles and landed, later that morning, in the Secret Archive’s reading room. Some reading rooms—the Duke Humphrey Room of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, the old British Library’s central reading room, or Bologna’s Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio, for example—add inspiring elements of aesthetic pleasure to the other joys of scholarship. The Vatican Archive reading room, by contrast, seemed all business to me, sternly utilitarian and largely unmemorable.

I don’t remember admiring it much during waits for my three daily manuscript requests to be filled at appointed times. I recall little about the room at all, in fact, except for a bank of tall windows to the east, plus the inevitable color photograph of a familiar preeminent prelate, keeping watch from high on the wall. Several years later I ran across an old photograph of the reading room, showing a couple of neoclassical statues in shallow niches and a few other decorative touches. They had been there along, but they seem never to have tempered my memory’s impression of the room’s severity. I whiled away the wait by discreetly watching others at work.

A perpetually jovial, scratchy brown Capuchin friar, resembling an extra in some crowd behind Charlton Heston in The Agony and the Ecstasy, was there every day for months. He often sat in splendid isolation (at least on warm summer days), a smile on his face and a glint in his eye, too caught up in chronicling the history of his order to give much thought to bathing.

There was the young archival careerist who, rumor said, had married well into some secular branch of the Vatican bureaucracy. He came and went as he pleased, apparently on no fixed research schedule. Often he cruised around the room restlessly. Some readers allegedly never left their manuscripts open if they temporarily left their desks, imagining he might snap up an important unattended discovery of theirs as he glided past.

One young female researcher assumed a faintly defensive posture whenever a manuscript delivery clerk went by. She would apologize that she did nothing to encourage their attentions. It was just that summertime was open season on attractive young foreign women—particularly for delivery clerks in the throes of midlife crisis.

Often in residence, usually down front and happily in view, sat a tall, distinguished aging gentleman in a dated double-breasted suit, his preternaturally black hair slicked straight back, 1930s style. Apart from his impressive bulk, he resembled the Sesame Street character who had taught many Americans in the room to count. Nicknamed “the count” by American admirers, he actually was a count who held court on the mornings when he showed up. How he had managed to write an unremitting stream of books and articles was a mystery. He never sat for more than half an hour and hardly untied a bundle of documents before someone, anywhere from twenty-five to eighty-five, walked up and shook hands. Then off they went to the Vatican bar.

The Vatican bar, the archive’s chief concession to creature comforts, occupies a tiny cleft in the back wall of a bright, pleasant courtyard between the Vatican Archive and the Vatican Library. The bar serves up deeply discounted fare to Vatican employees. But it does not discriminate against scholars, who take carefully timed breaks within its lively, smoky haze.

The count always seemed delighted to share coffee, decades of archival experience, and batches of offprints. Any American who made the requisite self-introduction was promptly told of the count’s ottocentoancestor who had served in Washington during President Lincoln’s administration. The count even offered an occasional invitation, if not to his house on the Adriatic or a second in the north, at least to his pied-à-terre, not far from the Pantheon. I remember it as a caricature of a scholar’s study. Dusty, dry, close, as if nobody lived there. Dimly lit by shafts of light through gaps in the heavy curtains, everything in a subtly varied palette of cappuccino, caffe latte, espresso, every surface piled with papers and stacks of the inevitable offprints. The desk, under a precarious pyramid of books, had its top drawers wide open, twin towers of volumes rising two feet or more from inside. A scholar of a decidedly old school, untroubled by deconstruction, cultural studies, and Foucault, the count had crafted a balance of affable generosity and his own brand of scholarly productivity.

Back at the archive reading room, the general anxiety level spiked around any new arrival. Tentatively wandering around the reference room, pocket dictionary in hand, submitting request forms, rebuffed if they exceeded the daily quota, reprimanded if the collocation number failed to fit the paradigm, most novices sat tensely awaiting the first items. Eyes shifted from the keeper’s desk to other readers, attempting to divine the modus operandi in the absence of much official guidance.

It had always been this way. When the archive began officially to admit outsiders in the 1880s, one confused novice researcher’s request for a word or two of advice drew exactly that. The comparatively benign second custodian Pietro Wenzel responded with a smile, “Bisogna pescare”— “You have to go fishing.”

The “hands off” administrative attitude grew more severe by 1927: “Whoever for his own convenience needlessly avoids carrying out normal research work in the indices and habitually troubles archivists, scriptors, and ushers will render himself unwelcome.” In the late 1960s Maria Luisa Ambrosini summed up the archive’s daunting reputation in a book whose reprint from the 1990s included her discouraging remark on its back cover: “The difficulties of research are so great that sometimes a student, having enthusiastically gone through the complicated procedures of getting permission to work in the Archives, disappears after a few days’ work and never shows up again. But for persons with greater frustration tolerance, work there is rather pleasant.”

Little wonder, then, that a new arrival might feel anxious. In addition, some American scholars had only a couple of weeks or so before their prebooked cheap return flights. And to top it off, the archive closes for the day at lunchtime. Hence they were first in line at opening and last to leave before lunch, with no time for coffee in the Vatican bar.

Nobody in the Vatican employ was likely to tell novices in basic training that while the archive officially closes at lunchtime, it reopens unofficially in the afternoon and remains open another three hours. Researchers from out of town need only request a permesso pomeridiano (afternoon pass). Then they can return after lunch and continue to work in the largely empty and much less frenetic reading room until early evening. But back in the 1980s, you had somehow to learn about the existence of this permesso. Nobody who worked there was likely to tell you—though they would issue one if you asked.

I was lucky. From day one, I benefitted from the experienced guidance of a former student, by then a veteran of several Vatican tours of duty. She had revealed the secret of the permesso pomeridiano even before my first day, as well as other essential Roman and Vatican survival tips. How to navigate the number 64 bus, which plies the route from Central Station through town to the Vatican. Tourists trapped on bus 64 draw pickpockets, who find the crush of standees easy pickings. Her most prized secret: how to visit the Sistine Chapel, even during high season, and still have the place virtually to yourself.

The archive’s American veterans generally made sure other new arrivals experienced similar kindness. No need for them to squander their afternoons visiting churches, museums, and Roman ruins, lingering outdoors over a late lunch, or sipping coffee in Piazza Navona. After all, they could be slogging through a few more buste in the archive, thanks to a permesso pomeridiano of their own.

I found a seat among the music veterans, picking their way through fourteenth- and fifteenth-century papal supplications registers. They searched for the great (Du Fay, Josquin, Busnoys) and the not so great but nonetheless significant. I began sifting for nun musicians in the buste of the Bishops and Regulars. Most researchers sat in intense concentration, negotiating page after page of impenetrable text, going as fast as they dared. Silence was the rule, except for the memorable time when “Holy shit!” scorched the ears of scandalized Vatican clerks. The room waited for the color portrait to tumble from the wall. The late fifteenth century’s most important composer had just emerged from hiding in my veteran friend’s latest volume of papal supplications.

Such Little Jack Horner moments (pulling out a music historical plum) hardly ever happened. More commonly, all endured prolonged fallow periods, a reality of archival research. One musicologist on an especially specific hunt once spent the whole summer slowly turning pages and finding nothing at all. But as I flipped documents, waiting for the odd detail of musical information to surface, I uncovered a wealth of alternative detail about sixteenth- and seventeenth-century convent life.

With pleasant regularity, something appeared that was diverting or eye-opening. Often just an amusing anecdote to relate during breaks in the Vatican bar. Nuns from Fabriano in 1650, for example, complaining about sweating youths (“most of them half naked”) so bold as to play soccer right outside the convent gate. “With nothing but dirty and indecent words and execrable blasphemies, they offend their chaste ears” (though apparently the gaggle of late-blooming soccer fans who overheard the youths while discreetly peering around the convent gate to watch willingly risked such aural damage). After a day or two, whenever I chuckled, my veteran deskmate began to ask, “All right. What did you find now?”

These nuns’ adventures and misadventures didn’t fit my 1980s musicological agenda, but they were too compelling to consign back to archival oblivion. Who knew how long it might be before someone else requested that busta? Many buste appeared never to have been opened since the secretary of the Sacred Congregation sent them off to the archive. Before the end of that first Vatican tour, my deskmate suggested that someday I should write a book retelling some of those forgotten tales.

This book offers five of the most interesting of these histories. Each relates a singular response to the cloistered life. All touch off major crises. They disrupt the convent status quo, provoking aftershocks that might continue for generations. They reveal the incapacities of hierarchically imposed systems of external oversight and control. Given these realities, they sometimes even destroy their communities.

“Aut Virum Aut Murum Oportet Mulierem Habere”

“A woman should have a husband or a wall.” This late medieval aphorism remained equally apt in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italy. A respectable woman’s choice—actually, her father’s, uncle’s, or brother’s choice for her—was either marriage or the convent. Italy had not seen such a boom in female monasticism since the late 1200s. But the old proverb might need updating for 1575: “Only one daughter should have a husband, and the rest should have a wall.”

The wealth of Renaissance aristocratic families had to be kept intact. Husbands wanted bigger dowries, and too many dowries drained the family coffers. Convents wanted dowries too, and genteel families recognized them as a necessary evil. Otherwise any sort of girl might get in. But convents settled for a fraction of what a husband demanded.

So while one daughter was commonly groomed for the marriage market, the rest were regularly bound over to the cloister. Often not on their own, however. To soften the transition, aristocratic sisters went off together, usually in twos, though sometimes in threes or even fours. Rome tried to keep the lid on it by limiting sisters to a single pair per convent. This discouraged strong family ties and convent factions. Exceptions frequently proved the rule, however, especially for the powerful. The Chigi family from Siena, who sent three cardinals off to Rome after 1650 (one to become Pope Alexander VII), deposited no fewer than seven sisters at San Girolamo in Campansi. Nothing quite this extreme appears in subsequent chapters of this book. But sisterhood is an important issue at San Lorenzo in chapter 2; sibling dynamics loom notably larger at Santa Maria Nuova in chapter 4; and they are an overweening factor at San Niccolò di Strozzi in chapter 3. There the cloistered community consisted entirely of sisters, aunts, and cousins from a single family.

In terms of numbers, nuns could not be called marginalized. In Bologna around 1630, nuns made up 14 percent of the population. For those who really mattered—the nobility—the percentages ran much higher. In seventeenth-century Milan, no fewer than 75 percent of genteel women lived behind convent walls. Their families might contain more nuns than wives. Visiting the family could mean an afternoon before the grated windows of some convent parlatorio (visiting room or parlor).

The convent constituted the expected, unquestioned life option for many girls. Parents’ strategies of encouragement and persuasion disguised where enticement ended and coercion began. Since cloistered aunties were delighted to see baby nieces, girls often learned about the cloister in earliest childhood. Occasionally they were even stuffed into the convent ruota, or “turn”—a rotating, barrel-shaped device with a pie-shaped wedge cut out, used to transfer goods from the world to the cloister without face-to-face contact—for a spin and a quick cuddle with a doting relative. This meant, technically, that they were automatically excommunicated for violating clausura (monastic enclosure). But it was the grown-ups who paid the price and dealt with subsequent hassles. Little girls might even become keen to join favorite relatives inside the convent. If a pair of sisters joined a pair of aunts (and sometimes also a pair of great-aunts), so much the better.

It helped if potential postulants arrived early, before experiencing life’s meager alternatives for women. The church set a minimum age of seven, with the additional stipulation that monastic profession must follow by age twenty-five. Exceptions to both minimum and maximum were regularly given the blind eye. A girl’s entry at the exceedingly tender age of two may have been exceptional, but it happened occasionally. Extenuating circumstances and the open arms of a childless cloistered aunt were commonly involved, when the convent became a haven in times of family crisis. The death of the girl’s mother or the absence of a female guardian at home was the most common cause. Even an outspoken Bolognese opponent of forcing girls into convents recognized an unpleasant reality of sixteenth-century Italy. “Cloistering women may be necessary, so that young girls aren’t left alone in their paternal home, at risk of losing their honor—not only to outsiders, but also to the servants. Or, what is worse, even to their own brothers or perhaps to their own fathers.”

Families also softened the transition from the world by making the convent as much like home as possible. Genteel monastic houses, especially those that did not practice the “common life” (in which everything was meant to be shared), allowed girls to bring opulent convent trousseaus. Since their monastic rule forbade nuns to own property, they would simply sign everything over to the abbess, who would then hand it all right back on loan. Several inventories from such reciprocal agreements survive from aristocratic Bolognese convents. What they record is a far cry from pallets, sackcloth, and ashes: bedsteads of hardwood, with feather mattresses, comforters, and different coverlets for summer and winter; walnut chests, chairs, and the occasional armoire; elaborate curtains, often embroidered, for windows, beds, and doorways; copper, brass, and pewter vessels; the occasional birdcage with a finch inside; paintings with gilded frames; and, for the musical, the occasional harpsichord, lute, harp, viol, violin, bass viol, or trombone (often outlawed, but useful for the bass part in convent polyphony).

Where a private chapel might have been uncommon at home, a nun’s own altar might rival that of modest churches, with a painting over it, sometimes with an elaborate cover as well as a frame, candlesticks, a crucifix, a choice of altar frontals and altar cloths. Other refinements included silver and ivory thimbles, silver boxes, silver pens, silver cups, silver and ivory toothpicks. In some cases, a bedroom at home could not have been much grander.

On rare occasions, wealthy fathers provided not only furnishings but even the rooms to hold them. A daughter’s new convent quarters might be built from the foundation up or reconfigured within existing buildings at family expense. Such family quarters were sometimes handed along to the next generation: a discreet form of female inheritance, usefully preserving another, less widely recognized line of the family’s patrimony (or matrimony).

Commonly, after several years as an educanda or resident student, the would-be nun’s formal acceptance was voted on by the professed nuns. The Council of Trent had stipulated this should not happen before age fifteen, though convents and parents found creative ways to secure the girl’s place much earlier. A “loan” of the girl’s dowry, subsequently canceled at the appropriate time, worked nicely. Ultimately, at whatever time it happened, the girl received her novice’s habit and her religious name as part of a formal clothing ceremony attended by family and friends.

During her novitiate year, she was to live apart from the professed nuns while she learned the religious life according to the rule of her particular order. Then the nuns formally voted a second time, to accept her as a “choir” nun. The novice received the black veil of a professed nun and promised to live in perpetual poverty, chastity, and obedience. Nuns and their male superiors seem often to have differed in their interpretation of the first and last of these. Lavish rituals of profession came to rival secular weddings in opulence, though the church hierarchy fought a losing battle to simplify them.

With the reimposition of strict monastic enclosure after the Council of Trent, even some in the church hierarchy recognized the importance of making nuns’ confined, interior world pleasant and attractive. A Milanese convent architect of the late 1500s observed, “They should have agreeable places—gardens, fields, loggias, workrooms, windows that catch the light—but all situated inside. They shouldn’t be locked up like slaves. Enclosed in their convents and churches, they may appropriately enjoy large, comfortable quarters, spacious cloisters, fair gardens, and other necessities of a decent, human life.”

The covered arcades of a central cloister most aptly fit the architect’s requirements. Enclosing a large interior space, open to air and light but cut off from the world, often with gardens and a well at the center, the cloister offered the most convenient place for fresh air and exercise, even in inclement weather.

At the other extreme, contrasting with the cloister’s seclusion, the parlatorio offered more suspect recreation. Nuns visited their families there, seated before large, grilled windows that separated the nuns’ inner chamber from the public’s outer room. The parlatorio was contested territory, the site of worldly distractions that threatened a nun’s interior life, at least in her superiors’ view. A signed license from the local nuns’ vicar could be required for admission (though laxity about this requirement seems to have been endemic). Some bishops attempted to close down the parlatorio on church holidays. They fought a losing battle to control parlatorio shenanigans during carnival, as chapter 6 clearly demonstrates. Chapter 2 reveals the parlatorio at San Lorenzo in Bologna as an eye-opening, lively center of secularized convent culture year-round—even including cloister romance—which sent the church hierarchy to red alert.

The convent chapel was the second most significant meeting place of the cloister and the world. Its central feature was its double church: an inner chapel for the nuns, shut off from an outer public chapel, which often served as the parish church. (A floor plan of Santa Maria Nuova’s inner and outer churches appears as figure 4.4.) A solid wall usually divided the two so emphatically that visitors to the public church might not even realize there were nuns close by. The barrier was pierced by a grilled window above the public church’s high altar. When a priest celebrating Mass there elevated the host at the consecration, it became visible to the nuns, following the Mass invisibly in their inner chapel, whose altar backed up to the same window.

Even the priest could not enter the nuns’ chapel without special license. For necessary, unavoidable contacts with the nuns, there were other breaks in the chapel wall. A smaller, curtained (inevitably) grilled window gave the nuns access to communion. Another small window might also provide a place for their confessions to be heard. A ruota was embedded in the wall of the sacristy nearby. Items such as Mass vestments could be placed in the ruota by the sacristan on the nuns’ side; it could then be rotated and the items removed by the priest in the public church. A second, larger ruota, often situated in the parlatorio, was used for bulkier convent supplies. This was where visiting small children might incur excommunication by going for a ride to see their cloistered relatives face-to-face. On rare occasions a particularly diminutive nun prone to wanderlust might even stuff herself in the ruota and go AWOL.

The organ window or the grilled windows of nuns’ choir lofts in the inner church also penetrated the chapel walls. For the church hierarchy, these were as dangerous as the grilles of the parlatorio. They lured audiences to convent churches merely to hear the nuns sing. They tempted the nuns to sing to the world and not to heaven. Choir lofts therefore were second only to parlatorios as convent battlegrounds where musical nuns opposed their bishops.

Churchmen were responding to a rising tide of enthusiasm for nuns’ singing—on both sides of the convent wall. It would crest by the 1650s, notably in such cities as Milan, Bologna, and Rome, then gradually ebb during the later 1600s and on into the late 1700s.

Nuns had been singing since the beginning, of course. In fact the primary job, the so-called opus Dei (work of God), of professed, “choir” nuns, had always been to sing the daily round of chapel services. One wonders, however, if anyone but God chose to listen much before 1550. Before then, convent music seems to have been primarily Gregorian chant. Some of it was artfully florid. But much Gregorian chant was extremely simple, and it involved only one melodic line—no harmony. Hence its other name, plainchant.

Judging by surviving archival and musical sources, the 1500s witnessed a striking expansion of convent singing into the realm of polyphony—choral singing in parts, similar to what men had been performing in cathedrals for centuries. This richer, more immediately attractive music, the kind associated with Josquin des Prez or Palestrina, contrasted markedly with sober plainchant.

What distinguished nuns’ choral singing from that in other Catholic churches (whose choirs included no women—ever) was the character of the voices, particularly the highest voices. Sopranos, altos, tenors—all were women. Though a convent in Ferrara boasted a “singular and stupendous bass,” the bass viol or (when they could get away with it) a trombone often took the bottom part in convent choirs.

In the convent there were no choirboys, who had to be trained for years and really knew what they were doing for only a year or two before their voices changed. In the meantime, the boys’ lack of expertise was often apparent. Convent choirs also contained no adult male “falsettists,” or countertenors, specially trained to sing the higher parts, artfully at the best of times, but hooting, straining, and “false” at the worst. There were also none of those curious novelties, castrati, who thanks to anatomical modifications before puberty combined a boy’s larynx with a man’s chest and lungs. Castrati began to appear in Catholic Church choirs about the same time choral singing was on the rise in convent choirs; the first castrato joined the Sistine Chapel in 1562. Yet too often parents’ anatomical gamble with their musical sons’ future did not quite pay off. Many altered offspring landed not in the Sistine Chapel but in some provincial cathedral, and that assuming their soprano voice range survived the change. Well after 1750 the touring English music historian Charles Burney found little good to say of them: “Indeed all the musici [castrati] in the churches at present are made up of the refuse of the opera houses, and it is very rare to meet with a tolerable voice upon the establishment in any church throughout Italy.”

So convent choral singing offered a novel, exciting sonority. When the nuns were in top form, theirs could be among the best sacred singing available, sometimes even better than in the local cathedral. No wonder convent choirs were soon among Italian cities’ top musical attractions, both for locals and for foreigners on grand tours. In 1602, for example, Philip Julius, Duke of Stettin-Pomerania, suggested that Milanese singing nuns rivaled Queen Elizabeth I’s choirboys. And 150 years later, Charles Burney willingly risked offending his Milanese hosts by skipping out before the second course at dinner, lest he miss even the beginning of services and any of the fine singing at the Convent of Santa Maria Maddalena.

For an aspiring female musician, the convent choir offered the only realistic opportunity for stardom that did not bear the stigma associated with public performance and the public stage. Any respectable girl, and certainly any respectable parent, knew that whenever a woman willingly lifted her voice in public song, she must have other, disreputable skills on offer too. As the early seventeenth-century English tourist Thomas Coryat put it when describing music’s place in the amorous arsenal of Venice’s notorious courtesans, “Shee will endevour to enchaunt thee partly with her melodious notes that shee warbles out upon her lute, and partly with that heart-tempting harmony of her voice.”

With public singing clearly off-limits for women of any quality, there were few options. Only the rarest supremely talented but also ultra-respectable female singer might hope to find employment in certain elite female ensembles at such courts as Ferrara, Mantua, and Florence. These were vigilantly and jealously guarded under the watchful eyes of their dukes. Such elite singers’ performances were so closely protected, respectable, and emphatically private that they became known as musica secreta. Young Laura Bovia in chapter 2, after being snubbed by the court of Mantua, eventually abandoned the convent of San Lorenzo in Bologna to join just such a group at the Florentine court.

The convent choir was also respectably “private,” since after all the nuns were singing behind the wall, in their own inner church. But their alluring voices echoed through the windows in the wall to music-loving audiences in their public church. These women may have been heard much more widely than any court songstress. All in all, then, the convent proved an attractive career option for the respectable girl with musical talent. Her parents—let’s face it—were unlikely to find her a husband in the world anyway, if another sister seemed riper for the marriage market.

When the professed “choir” nuns were not singing and praying in chapel several times during the day, they occupied themselves with useful work and recreation. The nature of it depended on the social standing of the house, but it was not of the ruder, manual sort. Refined houses (e.g., San Lorenzo, Santa Cristina, and Santa Maria Nuova in Bologna) concentrated on edible delicacies, realistic artificial flowers, or artificial fruit. Less socially exalted, more observant houses (Bologna’s San Gabriele or Santa Maria degli Angeli, for example) might sew religious habits or altar furnishings. Near the bottom of the pecking order, Bologna’s Convertite (reformed prostitutes) did fancy laundry (starching and pressing collars, ruffs, and fancy cuffs).

Lofty aristocrats—two generations from the Malvezzi family in chapter 4, for example—excelled at the most refined silk embroidery (not for sale, of course, but as their charitable chapel adornments). The aristocrats at San Niccolò di Strozzi (chapter 3) also kept indolence at bay by working in silk—but on the other end of production: raising the silkworms.

The nuns’ superiors might praise these various activities as laudable work. Not so music. One week an archbishop praised the good works of the Malvezzi nuns’ obsessive embroidering (chapter 4), with no suggestion that it might ever distract them from their prayers; the next, he might condemn, even punish, the singing nuns of Santa Cristina (chapter 6) for the fruits of their own dedicated chapel labors. Such suspicion and disapproval remained an abiding, fascinating incongruity of convent “work.”

A separate class of nuns, so-called converse, freed professed nuns for their chapel duties and for these more refined pursuits. Converse came from respectable lower-class families (“of honest parents,” as their convent obituaries commonly put it). They paid much smaller dowries and had no chapel responsibilities (except, of course, to keep it clean and take communion as required) and no voice in convent government. Their labors, involving all the menial work in the kitchen, chapel, fields, and gardens, made possible their superiors’ artistic, creative, and spiritual preoccupations. Each conversa also looked after three or four nuns’ day-to-day personal needs.

Converse have tended to be eclipsed by professe in convent historical studies, but the convent way of life absolutely could not have gone on without them. Several of these tales reveal that converse were at the center of convent life, though often invisible to those around them. The kitchen conversa Anna, at San Lorenzo (chapter 2), crops up repeatedly, and embarrassingly, because of her successful love magic. Another kitchen conversa, the generous but uppity Terentia Pulica (chapter 4), demonstrates the great divide between conversa and professa when she incurs the wrath of Maria Vinciguerra Malvezzi for her upstart behavior. The converse at San Niccolò di Strozzi (chapter 3) become key witnesses in the archbishop’s case against their betters, the nun arsonists.

True religious vocations, while by no means uncommon, were not the norm in the religious environments of several of these tales. Only one of the four aristocratic Malvezzi nuns at Santa Maria Nuova (chapter 4), for example, was remembered for outstanding religious devotion. It appears unlikely that any sister at San Niccolò di Strozzi (chapter 3) felt much sense of religious vocation. But many convent women seemed to construct lives for themselves that were tolerable, sometimes pleasant, and occasionally clearly “fulfilling.” Such fulfilling lives often did not fit the Vatican paradigm of single-minded spirituality, separation, and subordination. They might follow intellectual, creative, or imaginative paths—paths that would have remained closed to their sisters in the world or would have been harder to navigate there. Convent necrologies (which, admittedly, tend to say something good or nothing at all) suggest that cloistered communities found ways to recognize, accept, and make the best of such individual paths, so long as they did not exceed the bounds of convent culture as currently and internally defined by the nuns themselves. For the male church hierarchy, on the other hand, responses to such exceptional life paths were often quite another matter. The collisions between the two responses account for much of our present story.

Telling Tales Out of Archives

It is difficult to imagine a group of nun musicians conjuring up the devil, or a haughty nun philanthropist tearing down, ripping apart, and burning another nun’s chapel donation—not to mention an entire community of nuns deciding to burn down their convent. But documents in the Vatican Secret Archive and other Italian ecclesiastical and state archives show that these and the other extraordinary tales in following chapters “really happened.”

The first hints of these stories were revealed to the Sacred Congregation of Bishops and Regulars in Rome in much the same way as they emerge for a modern-day archival researcher. A provincial prelate’s initial, often arresting communication, which first appeared on the desk of the Congregation’s secretary, resurfaces centuries later in a bundle of documents on the archivist’s desk. It first calls attention to a crisis and may briefly describe it. The Sacred Congregation followed up by requesting additional information from the relevant bishop; latter-day researchers go searching for such information on their own. Both investigators wait for additional facts to surface, often for a good long time. The piecing together of the resultant story, whether in the sixteenth century or today, invariably requires investigation into the history that preceded and precipitated the crisis and prompted that first tantalizing document. Subsequent history of the crisis may continue to unfold long after that first document appeared on a Vatican bureaucrat’s desk—for months, years, even decades. Aftershocks of a singular event may continue for centuries. The same may be true of the paper trail the crisis left behind, which the archival sleuth tries to uncover, often for months, years, even decades.

I could not resist telling these tales in the way I recovered and experienced them myself. Judging by my sources, this often also reflected how cardinals in Rome or churchmen in the dioceses dealt with them. The resulting histories rarely lead down a clear linear path. Many intriguing cases vanish without further archival traces; others peter out after yielding only the odd additional detail in the buste of the Sacred Congregation. Sometimes additional documents that should appear in records for a particular month and year aren’t there. Cardinals in the Sacred Congregation were not immune to similar frustrations. Minutes of meetings occasionally complain about their own inability to recover records from previous deliberations, lost somewhere in previous decades’ voluminous paperwork.

The five tales told here were, of course, among the most interesting, but they also happily left perhaps the most complete paper trails. I hope my narratives convey more of the suspense I experienced in searching out and picking my way through their details, sidetracks, and dead ends and less of the confusion they frequently provoked along the way.

To lessen the confusion somewhat, I have limited the dizzying profusion of similar Italian names when they seemed likely to befuddle modern readers. Rather than relegate minor, unnamed players in these dramas to the same anonymity they experienced in their own day, however, I have included their names in the notes when they are quoted directly, but anonymously, in the text. In the interest of clarity, a list of dramatis personae cataloging the chief players in each chapter appears at the beginning of the book.

The singular stories often emerge in vivid detail, with extensive “eyewitness testimony” and firsthand accounts. Their events are “true” to the extent that the sources document their details. Whether everything “really happened” as I tell it is difficult to say. These tales were largely filtered through male clerics. That had long been true for the voices of religious women, of course, both the paradigmatically holy ones and the sort who populate these pages.

In some of the following chapters, the effect of a prelate’s own point of view about the story becomes immediately obvious. The archbishop of Reggio Calabria in chapter 3 carefully chose his witnesses to create the most damning impression of the nun arsonists, whom he silences totally, for reasons I try to tease out from between the lines. Angela Aurelia Mogna, whose flight from Santa Maria degli Angeli in Pavia initiates the saga in chapter 5, may have been interviewed briefly at the beginning of the vicar-general’s investigation of her misadventure, but then she virtually disappears. We never hear directly from her again, by contrast with all the other chief protagonists in her story, many of whom quote her alleged remarks. The haughty and impatient Donna Maria Vinciguerra Malvezzi of chapter 4 exceptionally takes some initiative by writing to Rome in her own defense, but we nevertheless hear her side chiefly from the Bolognese archbishop. He seems most interested, however, in justifying his own possible negligence. The opera-loving Christina Cavazza of chapter 6 has no voice of her own for the first several years of her misadventures. We know her through a Bolognese archbishop with whom she already had a “history” and through her female superiors who, I suggest, were following agendas of their own. When Donna Christina eventually takes the bold step of speaking up for herself, the offended Archbishop Boncompagni washes his hands of her. During the last two decades of her story, however, her own voice grows louder, more independent, and quite eloquent as she negotiates her life journey among and around several powerful priests.

It may surprise some readers that Maestro Eliseo Capis, the Bolognese master inquisitor in chapter 2, should convey most directly the voices of the women whose devilish conjuring he was obliged to investigate. Does that mean that what his scribe recorded was closer to the “truth”? Some witnesses may simply have believed things happened as they later recounted. Others may have bent their truths to suit the circumstances. Episcopal visitors or inquisitors of the Holy Office chose their questions carefully to fit their own objectives, as several chapters illustrate. Witnesses called before them might be only as candid as they dared, or as their quick wits counseled them to be. They may have helpfully embroidered their responses, picking up threads dropped encouragingly by their priestly interrogators.

On the other hand, convent chroniclers, composing their narratives in less constrained circumstances, nevertheless had vested interests in showing their houses in the best possible light. If my own extremely well-churched spinster great-aunt was willing in her records of our family to shift an occasional younger relation’s marriage date back a few months to accommodate a respectable nine months before the inevitable “blessed event,” I wouldn’t really expect convent chroniclers to resist making similar historical improvements on what “really happened.”

In recounting these stories, I suspect I have indulged in less embroidery than some of my historical witnesses. The original sources can be extraordinarily vivid without additional help from me. For example, all the soggy details of Sister Angela Aurelia Mogna’s escape from Santa Maria degli Angeli (chapter 5), hand in hand with the young Giovanna Balcona, and the sorry condition of their bedridden lower-class nosy next-door neighbors come from primary sources. On rare occasions when, admittedly, I may sail dangerously into less clearly charted waters, I take readers into my confidence in the notes. No source documents the Bolognese master inquisitor’s early morning visit to the external church at the convent of San Lorenzo (chapter 2) before beginning his (documented) investigation in the parlatorio, for example. But various sources do document the appearance of the convent, its chapel and altars, the probable character of its organ, and its altarpiece, which he observes in that (undocumented) brief side trip I send him on.

Since these women have been forgotten and silent for so long, I have let them speak at length, as often and for as long as I thought modern readers’ patience would tolerate. Language that seems charming when heard in Masterpiece Theater costume dramas may turn tedious rather more quickly on the page. It is also important to recognize that the constrained circumstances in which the nuns speak, whether in formal written petitions to their male superiors or in testimony before interrogators of the church hierarchy, affect what they say and how they say it. They tend to join clause after clause for page after page with few breaks. I have separated these unremitting run-on sentences into more clearly comprehensible units, trimmed reiterations and repetitive phrases, and omitted text that did not seem absolutely essential to the narrative. In the resulting translated quotations, I have suppressed the ellipses that would have peppered similar extracts in the most scholarly discourse. In some cases a moderate-length paragraph in my quoted extract might have stretched over a page or two of the original manuscript. I have often simplified syntax (avoiding the strings of gerunds so popular in the original documents, for example). Successions of such regularly repeated formulas as “Your Most Reverend and Illustrious Lordship” have sometimes been simplified or replaced with “you.” In the interests of clarity, I have occasionally sorted successions of confusing third-person pronouns into their equivalent proper names.

In re-creating dialogue or scenes involving direct quotation, I have had to modify the originals in other significant ways. Scribes recorded the words and comments of inquisitors of the Holy Office in the third person, for example, with witnesses’ responses in the first person. In my translations, I have reconstructed both sides in normal dialogue form, closer to what happened on the spot. Where witnesses described another person’s words, I have occasionally reinstituted first person and quotation marks (which my sources never include, even when quoting directly) in my telling.

For serious poetry, as well as for frivolous verses such as “Vu ch’ave quella cosetta” quoted above (where my translations may reflect the spirit as much as the letter of the original), the Italian original precedes my translation. Scholars will also find citations of my original sources for my other translations in the notes, should they be concerned that my own ventriloquism might rival that of the priests who are rarely far removed from the surface of these narratives.

Nuns Behaving Badly was inspired in part by the writings of Carlo Ginzburg and Natalie Davis, whose The Cheese and the Worms and The Return of Martin Guerre, in the subdiscipline of “new history” dubbed “microhistory,” have captured the imagination of readers well beyond the academy. But the present narratives may call to mind much older traditions of telling tales, most familiar from Chaucer and Boccaccio. The book’s its episodic character is perhaps more akin to that approach than to the more focused, penetrating view of most microhistory. I confess to having been keen to reconstruct and retell stories from a little-known corner of Italian history in a comparatively uncomplicated way. If the rhythms of the little book’s organization and its less theoretical approach encourage it to be deposited on bedside tables, atop toilet tanks, or, particularly, inside a travel bag on an overnight flight to Milan or Rome, it will perhaps have found an appropriate berth.

And with that word we ryden forth oure weye,

And he bigan with right a myrie cheere

His tale anon, and seyde as ye may here.

—Prologue, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from chapter 1 of Nuns Behaving Badly: Tales of Music, Magic, Art, and Arson in the Convents of Italy by Craig A. Monson, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2010 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Daiva Markelis

Nuns Behaving Badly: Tales of Music, Magic, Art, and Arson in the Convents of Italy

©2010, 264 pages, 25 halftones

Cloth $35.00 ISBN: 9780226534619

E-book $35.00 ISBN: 9780226534626

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Nuns Behaving Badly.

See also:

- Moremedieval studies titles

- More religion titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog