An excerpt from

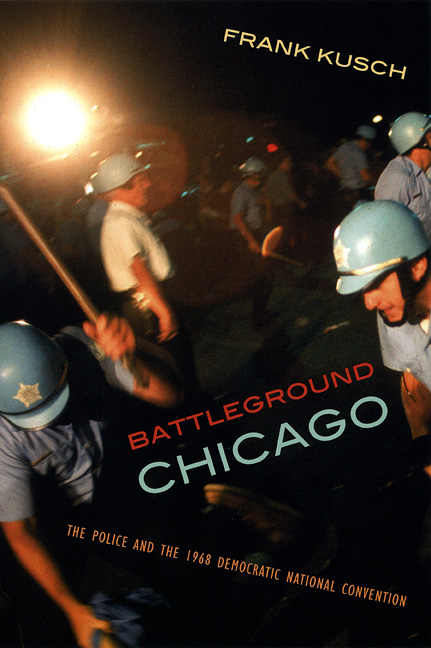

Battleground Chicago

The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention

Frank Kusch

“A Longhair Was a Longhair”

By early 1967, police officers admitted that they had difficulty separating radicals from counterculture enthusiasts. Cop Ray Mihalicz remembers that each day his job became increasingly difficult. “I remember the years before—the radicals used to wear black all over or turtlenecks when it was hot enough to fry an egg on the hood of your car and sunglasses on cloudy days. By the time the war heated up, mid-decade, I suppose, the bad ones and the normal kids—if you can call them normal—all looked the same. It was like they wore this uniform that said, ‘I don’t belong in this society, look out for me.’ They might as well put a bull’s eye on their back.”

Other officers suggest it was as simple as “a longhair was a longhair.” Says Ernie Bellows, “I’m not sure how people think that we should have been able to tell these people apart; they didn’t look any different, they didn’t speak any different, dress any different, their signs said the same thing; they were trouble—we read about them, and they spoke of causing trouble in our city for the convention. Poisoning things, having sex on the streets, and hurting delegates. It was all bad, and we could hear it coming down the pike, and smell it, too.” Other officers agree. “There was no distinguishing hippies, Yippies, Diggies, SDSers, and all of those radical groups,” recalls former cop Mel Latanzio. “They went under different names, but we kept our eyes on all of them. I think they were pretending that they were different at times, but that was just a ploy, because when they got on the street, they all behaved the same way. Your regular patrolman was not going to be able to tell these people apart, and they didn’t seem to care what we thought, anyway; even if they weren’t trouble, they wanted to look the part.”

Considering the Yippie efforts to blur the line between flower children and political activists, such police attitudes are not surprising. Indeed, Hoffman had no illusions about himself. In a letter to Stokely Carmichael, he made light of his peace and love credentials. “We are working on a huge Youth Festival in Chicago at the time of the Democratic Convention. I hope to get to participate. I’m currently on trial for supposedly hitting a cop with a bottle in a demonstration. I can’t imagine what they are talking about, me being a flower child and all that.”

Many in the movement knew that they were getting under the skin of those in authority. “Yippies are voluntary Niggers,” observed Realist editor Paul Krassner. “We live outside the system, and those inside it despise and fear us.” Krassner was more right than perhaps he even knew. Hoffman had gotten his way, making police believe that hippies were unpredictable and dangerous, and therefore would more likely bring about a crisis mentality on Chicago streets as the convention neared. Police officer Grant Brown was one of many cops who didn’t know what to expect. “The problem for all of us was that we didn’t know what or where the hit was going to come from. We worried about the delegates, we worried about the infrastructure, the power, the water, and worried about them putting acid in the water—we didn’t know what was going to happen, and there was fear, all right, as silly as some of that fear may seem now.”

At issue was the belief that anyone donning counterculture dress was a threat. There were no more “innocent flower children.” Former cop Norm Nelson, for example, viewed the Yippies as what the hippies had become, having now abandoned all pretense of flower power and peace. Nelson had read about them in the local papers. “We knew who they were—they had metamorphosed into the real thing. Yippie was the myth. It was the coming of war; from ’67 on it was a battle, and they were showing their true colors in the weeks and months leading up to the convention in our city.… Let’s put it this way, we were ready for those SOBs.”

Though less strident in their opinion, other former cops, such as Len Colsky, tend to agree with the basic sentiment. Colsky recalls that even though police tried to distinguish between peaceful protesters and troublemakers, the process had be come increasingly difficult. “We were not branding everyone the same. There were peaceniks that a lot of us knew would not hurt a fly. You moved in on them and arrested them and they went like Raggedy Ann dolls in your arms; and [there were] others who were holding protests. And in America, if you don’t do damage to private property, you’re okay, and we could tell them apart often.” Colsky recalls, though, that situations became more difficult to interpret as the decade wore on. “Things became very confusing. I remember well in 1968 where it was hard to distinguish the hippies from the criminals; they all looked the same. And the ones who were causing trouble and promising to do damage looked and dressed like hippies.”

Other cops admit, however, that there may have been a desire to see hippies and the counterculture as the same—radicals looking to do harm. Says former officer Warren MacAulay, “I know people who wore a uniform who really didn’t care—they hated the entire generation and they used any excuse they could find to go after them and teach them a lesson. These Yipps with their tough talk were making that very easy for some of the members.”

Indeed, Yippie actions during the March Grand Central Station incident in New York City had made its way to members of the Chicago Police Department. Evidence of specific communications between departments came following the arrest of Jerry Rubin by New York police in June. Rubin filed a charge of police brutality against officers at the Ninth Precinct following the incident where police allegedly kicked him during his arrest. Abbie Hoffman also accused three of the arresting officers of making “verbal and physical attacks” against him “for political reasons.” During a press conference, Rubin complained, “all their questions centered on my politics.” He made it clear that the officers asked specific questions on Yippie plans for a major demonstration in Chicago that August.

Some Chicago police officers recall colleagues having conversations with other jurisdictions beginning in 1967 after the march on the Pentagon. What increased communications was the radical Yippies. Officer Marlin Rowden recalls that some in his district had friends in other cities with whom they had regular correspondence. “I don’t think that is too difficult to believe, especially when things began to get out of control. Guys would talk shop, sometimes with some of their brothers they had in the academy, cousins, friends, hunting buddies. It was all kind of informal, but it picked up after what happened at the Pentagon and with some of the members in Oakland. We wanted to know what was going on with some of these extremist groups. So, there was some talk back-and-forth, but all of that increased prior to the Democrat’s convention. We wanted to find out what was happening with some of these fringe groups, such as the Yippies. If we could scare them from coming in the first place, so be it.”

There are indications that discussions were much more formal. “I think that it was tactical,” recalls Kelly Frederickson.“ We exchanged intelligence and information all the time. Especially between district commanders. What was important filtered down to us, the rest, and the volume of traffic, I don’t know, but remember, this is just part of good police procedures. It’s not a conspiracy.” Indeed such practices were part of the routine work of police intelligence divisions, such as Chicago’s infamous subversive unit dubbed the Red Squad that worked to infiltrate radical groups to discern first hand the plans of “radical elements.”

In the weeks and months leading to the August convention, paranoia and hatred were fueled by pronouncements emanating from the fringes of the movement. Fringe material became fodder for police with an ear to the ground or an eye on the local paper. “The press loved these crazies,” writes historian Allen Matusow. “Frightened officials took their wildest fantasies literally; and the myth of the Yippie grew.” The most telling reaction was how Mayor Richard Daley seized on the threats to restrict permits for marches and ordered curfews for city parks. These threats, which included the absurd Yippie boast to place LSD into the city’s water supply, had predictable results. Daley placed police officers at the city’s filtration plants twenty-four hours a day. Police were ordered to guard every pumping station and filtration plant starting the Saturday before the convention.

Chicago quickly became an inhospitable place for would-be demonstrators, as Daley refused all permits for marches and parades. Rennie Davis enlisted the help of the Justice Department, arguing with good reason that permits would lower the threats of violence between protesters and police. Although justice official Roger Wilkins met with Daley and city officials, he got nowhere. With one week before the start of the convention, Mobe organizers went to federal court to gain permits for the convention, but they were denied there as well. Organizers also learned that police would enforce a strict 11 P.M. curfew.

There was no doubt that Hoffman and Rubin had succeeded by not only worsening an already tense situation but by helping to create a showdown between protesters and city officials over marches and gatherings. Bowing to fatalism, Hoffman admitted that from the start he knew Chicago was going to result in a fight. “My feeling that Chicago was in a total state of anarchy as far as the police mentality worked.” Hoffman admitted later while on trial for conspiracy. “I said that we were going to have to fight for every single thing, we were going to have to fight for the electricity, we were going to have to fight to have the stage come in, we were going to have to fight for every rock musician to play, that the whole week was going to be like that. I said that we should proceed with the festival as planned, we should try to do everything that we had come to Chicago to do even though the police and the city officials were standing in our way.”

All of this made planning for Chicago next to impossible. Hayden and Davis even failed in their last-ditch efforts to allow protesters to sleep in the parks. They knew that allowing protestors to camp overnight would keep the kids off the streets and avoid a housing shortage for visitors. Daley, however, did not intend to make concessions to demonstrators. Since April, he made it clear with his public statements that police would deal harshly with dissenters. The cantankerous mayor instead denied all permits and transformed the city into an armed camp.

“Fort Daley”

A week before the convention, the city of Chicago mobilized for combat. The special Chicago Police Department Task Force prepared for battle with 300 members patrolling in cars, armed with service revolvers, helmets, batons, mace, tear gas, gas masks, and one shotgun per car. Five hundred of these masks were delivered to the CPD one week prior to the convention. “No one is going to take over the streets,” blasted Daley. His cops were to be stationed on every street corner and the middle of every block in the downtown area. At the Conrad Hilton Hotel, which served as campaign headquarters and hosted Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Senator Eugene McCarthy, federal agents were to patrol the rooftops and the corridors, as well as the kitchen and service areas. Agents were to guard the candidates’ suites around the clock, checking everyone entering and exiting elevators. Police afforded similar protection to the Sheraton Blackstone across the street, where Senator George McGovern was to stay. The police warned the media not to take pictures through open windows in the area for fear of being mistaken for snipers.

It was no different at the amphitheater. The police sealed all the entrances on Halsted Street, while the owners of nearby buildings were ordered to close their windows during the convention. The department placed 1,500 uniformed officers outside the amphitheater, including snipers atop with binoculars and walkie-talkies. Telephones would connect officers to their counterparts inside, who were installed on catwalks overlooking the convention floor with binoculars.50 Security also included a cyclone fence topped with barbed wire (at the request of the Democratic National Committee) and sealed manhole covers. The streets surrounding the amphitheater were barred except for VIP vehicles. The readiness of Chicago’s fire department was also stepped up as Daley ordered the city’s 4,865 firefighters to work extra shifts beginning on the Sunday before the convention. The men would only have twenty-four hours off between shifts instead of the usual forty-eight, increasing the on-duty force by 600. One hundred and seventy-five men from the Fire Prevention Bureau were to be on duty inside the amphitheater, with twelve others at the hotels that were housing delegates.

For the president’s safety, the Secret Service planned to take Johnson to the amphitheater by helicopter. The surrounding airspace was turned into a no-fly zone for an altitude of 2,500 feet, except official convention business and police helicopters equipped with high-intensity lights to scan the tops of buildings near the amphitheater. This wall of security was not confined to the outside, as inside, delegates were to be joined by several hundred security personnel, some mingling among the delegates, while others watched from catwalks; female security personnel were stationed in the ladies’ washrooms. The security measures extended to protect the delegates traveling to and from the convention site. Delegates would travel in busses escorted by police motorcycles, followed by unmarked squad cars, with a police helicopter scanning the route from overhead. Even though the city spent $500,000 to beautify the area around the convention site, it could not hide the reality that the city encased the amphitheater in barbed wire. Making the site even less hospitable was its unfortunate location right next to the city’s stockyards. Two blocks away stood a pile of manure, seventy-feet wide and ten-feet high. The smell in the area was often overpowering.

Also overpowering was the amount of firepower assembled for the weeklong convention. The usual police contingent of 6,000 officers on the streets grew to 11,900 on twelve-hour shifts, up from the usual eight. The city requested the mobilization of 5,649 Illinois National Guardsmen, with an additional 5,000 on alert, bolstered by up to 1,000 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) officers and military intelligence officers. Waiting for signs of trouble in the suburbs would be 6,000 army troops, including members of the elite 101st Airborne Division. The men were to be equipped with bazookas and flamethrowers. While the military protected the suburbs, an unspoken fear was that black militants would try to disrupt the convention by firing on delegates from the decrepit high-rise public housing projects that overlooked portions of the Dan Ryan Expressway. Police helicopters patrolled the stretch looking for any sign of trouble.

Although the mayor’s office did not speak openly about this fear, there were concerns of rioting in the black neighborhoods, with the possibility of it spreading to the center of the city. This was especially true since significant police resources were to be pulled away from those areas of the city to protect the convention sites and the downtown parks. In the days leading to the convention, there were threats to attack police if they moved into black areas in force. Most black groups, however, did not intend to become involved in convention-week demonstrations. Calvin Lockeridge, who led the Black Consortium, an amalgamation of thirty-nine national and local black groups, made it clear that the convention was not for them. “We feel basically that this is a white folks’ thing.”

Most of the security precautions were not secret but highly publicized efforts to intimidate would-be travelers to Chicago. The precautions sent shockwaves through the movement. David Dellinger recalls the trepidation. “The two questions I was always asked were: (1) is there any chance that the police won’t create a bloodbath? (2) Are you sure that Tom and Rennie don’t want one?” Indeed, Daley’s saber-rattling dampened much of the earlier expectations for a huge influx of protesters into Chicago. Even two weeks prior to the convention J. Anthony Lukas wrote in the New York Times that a “conservative” estimate of protesters was 50,000 while the prediction of more than a million was “seemingly inflated.” Dellinger and the other Mobe leaders, however, had already abandoned their desire to bring large numbers of protesters to the convention. Racked by dissension and lack of direction, Daley’s tactics of stalling on permits and “shoot to kill” orders made the prospect of going to Chicago unattractive for other than the most ardent in the movement.

About 500 SDS members—a fraction of their number—planned to travel to Chicago, along with members of the Chicago Peace Council, the Communist Party, the Fifth Avenue Peace Parade Committee, and the Cleveland Area Peace Action Council. One group that planned to stay away was the Chicago Area Draft Resisters. Founder Richard Boardman said the decision to stay away reflected the organization’s attitude toward major protests. SDS had feared a bloodbath on the streets of Chicago and was reluctant to travel to the Windy City. For a while, this fear had strained relations between the organization and its former head, Tom Hayden, who believed that the convention was an important stand. SDS wanted highly organized, small groups of demonstrators, or “squad action.” The Chicago Seed, however, advised people to avoid the city. When it became apparent that the Yippies were not going to secure a permit for the Festival of Life in Lincoln Park, the Seed issued a statement urging people to stay away. “Don’t come to Chicago if you expect a five-day festival of life, music, and love. The word is out. Chicago may host a festival of blood.”

Awareness also grew of a rift within the Yippie leadership, including Jerry Rubin and Paul Krassner, who were thought to want to provoke violence with police, and the Chicago-based Yippies, who wanted to keep the festival peaceful and “life affirming.” However, as the convention neared, it looked as though there was little prospect for peace, with rumors within the movement that Rubin and Hoffman hoped police would turn the convention into a riot. Indeed, Rennie Davis admitted that the aim was “to force the police state to become more and more visible, yet somehow survive it.” Todd Gitlin knew that a hardcore element of the movement was ready for a fight. “Part of the New Left wanted a riot, then, but the streetfighters could not by themselves have brought it about,” wrote Gitlin. “For that, they needed the police. The sleeping dogs sat bolt upright, howled, bared their teeth, bit.”

News of how Daley’s police had treated peace marchers in April also had a negative impact on those willing to travel to Chicago. The belief was that if Daley felt that marchers had no right to express their views during a seemingly harmless peace march comprised of local Chicagoans in April, how would they react to thousands of out-of-town demonstrators during a national party convention with the eyes of the nation warching? In the days leading up to the convention, Daley tried to strike a more conciliatory tone, suggesting that protests would be permissible as long as they were done “peacefully and legally and rationally.” Two days later, the mayor made a point of welcoming all to Chicago.

It is only fitting that during this dynamic democratic process, there is present in our city a cross-section of representation of the voices of America—liberal, moderate, conservative, and radical, young and old, hawk and dove, hippy and square … and this is the way it should be because this is America.

Few bought Daley’s egalitarian prose such as when in July, speaking before the Amencan Legion, Daley promised, “as long as I am Mayor of this city, there will be law and order in the streets.” Daley knew he had the support of the citizens of Chicago. As Allen Matusow has deftly pointed out, “Daley knew that if push came to shove, the great mass of white Chicagoans who bathed prayed and pledged allegiance to the flag would have backed him all the way.” The mayor’s tough stance also had the support of the press. A week before the delegates arrival, the Sun-Times praised Daley’s “forthright” manner in establishing tough “ground rules.” The editorial said Daley was correct to eliminate any “irresponsible activites” on the part of demonstrators during convention week.

The veteran mayor also knew that the people of Chicago expected nothing less. On convention eve, citizens in the mayor’s neighborhood warned Yippies to stay away. Even minors were issumg warnings. “They better not come down here” a thirteen-year-old boy told a reporter for the New York Times. “We’ll get scissors and cut all their hair off.” A ten-year-old added “We'11 take their hippie chains and strangle them.” A neighborhood woman predicted ominously, “There will be slaughter. Just slaughter. On both sides, I guess. They better not come where they’re not wanted.” Another man who lived across the street from the mayor's house believed that the city would let police handle demonstrators. “I’m Polish and I don’t have much use for these people who sympathize with the Communists. [But] most people will just sit on their porch and watch.”

The veteran mayor was acutely aware that massive disturbances would damage his city’s reputation; losing control of protestors during the convention, he believed, would tarnish his Democratic Party and hurt its chances in the November election. Daley feared relenting and turning the streets over to the movement. Moreover, says Milton Viorst, little eclipsed Daley’s “loathing for young, white radicals.” To mitigate any possible damage, Daley also set out to restrict the media’s ability to cover the convention. He not only limited the numbers of press passes to the convention floor, but he restricted the press’s ability to cover street disturbances; Daley refused to let the netwoks run the cables necessary to operate the portable generators for their color cameras on the streets in front of the downtown hotels. Although the Mayor hoped to control the action on the streets, there was little he could do to forestall the growing split within the Democratic Party.

“Dump the Hump”

Few believed that the national convention would pass without incident either inside or outside the amphitheater. With Humphrey as the likely candidate, there was little hope that the ruling Democrats would be able to silence the antiwar crowds. A week before the convention, Senator George McGovern, head of the convention’s platform committee and a candidate for the party’s leadership, said that he didn’t think Humphrey could move away from Johnson’s policy even if he had wished. McGovern believed that the only way he could dislodge Humphrey from Johnson was by giving him a plank he could embrace. Although McGovern stated that the plank could not contain “any implication that we’ve been on the right course for the last four years,” he did not believe it was necessary to have one that would constitute a denunciation of the administration, thereby making it easier for Humphrey to accept.

The plank proposed by Senator Eugene McCarthy a week before the convention, however, left the front-runner with little room to maneuver. McCarthy’s plank declared, “The war in Vietnam has been an enormous cost in human life and in material resources. It has diverted our energies from pressing domestic problems and impaired our prestige in the world.” As McCarthy believed that neither side could win the war, his plank called for a negotiated settlement. He insisted that a new Democratic administration must immediately halt the bombing of North Vietnam, as well as all other attacks on its territory. Such a plank he said was “fully consistent with the expressed ideas of the late Senator Robert F. Kennedy.”

For his part, Humphrey tried to make the case that prior to the senator’s assassination, he and Kennedy held similar views on Vietnam. Richard Goodwin, McCarthy’s campaign coordinator for the presidency, who also worked for Kennedy at the time, said that if it were in fact true that Humphrey agreed with Kennedy, then the vice president should accept McCarthy’s plank. As the convention neared, it appeared that McCarthy wanted to exploit the issue for his own advantage. Humphrey was in a no-win position on the war, a looming issue threatening to divide the party, and one that the vice president was at pains to avoid. Humphrey’s aims were to deliver a war plank that was broad enough to bring together the party’s dissident factions, yet ambiguous enough to discreetly separate him from the polices of his soon-to-be-former boss. It was, for many reasons, a difficult proposition. “There is no difference of opinion on whether the objective is to get out of Vietnam,” stated a Humphrey adviser. “No one favors a strong hawkish position. The only problem is how to phrase a plank that looks ahead, emphasizes peace and does not gratuitously stab the Johnson administration.”

Humphrey, however, was associated not only with the administration’s polices of the previous four years, but with the decade’s failings, particularly the racial divisions and riots that racked numerous cities. With the charismatic Kennedy gone, McCarthy was seen as the last best hope in the Democratic Party to redress the racial divide. This division was especially acute in Chicago, still one of the most racially segregated of the bigger northem cities. One week prior to the convention, crowds cheered McCarthy during an appearance in a black Chicago neighborhood. Speaking in the city’s South Side, McCarthy drew warm applause as he endorsed black power. “No people,” McCarthy told a crowd at the Tabernacle Baptist Church, “have more reason and more right to organize politically.… I’m not really asking [for] your endorsement, but I hope you will consider my candidacy with a sound, harsh judgment.” Aware of Humphrey's vulnerability, McCarthy recieved the most enthusiastic applause when he stated that the system of party bosses made it difficult to challenge incumbents. Democrats, McCarthy explained, are “afraid to change the system. We tried to change it and whether we changed it or not we gave it one or two shakes and kept it alive.” He told the all-black crowd that if the Democrats select Humphrey to run against Nixon, the nation will be faced with choosing “between two echoes.”

By convention time, the antiwar movement reviled Humphrey more than anyone in the party. Sans Johnson, protestor wrath turned on the vice president. Protestors dogged his appearances, waiting for him following speaking engagements or in receiving lines. When Humphrey arrived to speak to a Liberal Party forum on August 17 in New York City, a hundred protestors confronted him on the street. When his motorcade appeared, they shrieked, “Killer!” and “Murderer!” while chanting “Dump the Hump.” At Stanford, an antiwar mob attacked his car yelling, “War Criminal!” and “Murderer!” Demeaning placards, gestures, and being spit in the face characterized much of his carmpaign. Despite the animosity, the veteran politician refused to turn his back on policies that he had followed (in public at least) so loyally for the previous four years. Such an act would be akin to admitting that he had been wrong on the war all along. Prior to arriving in Chicago, Humphrey made an appearance on Meet the Press and told a national television audience that there was no reason to disavow the president’s “basically sound” polices. The vice president naturally found little agreement in the antiwar movement that readied for battle in the Windy City.

“My Hand Twitched on My Nightstick”

Police helicopters hovered over Lincoln Park on convention eve as the tension rose and sides postured for position. From the view point of the police, the arriving antiwar crowds looked and acted like those Daley had been warning about for months. With helicopters circling, groups of long-haired young men practiced karate and judo in Lincoln Park, a mere three miles from the delegates’ hotels. Although much of the action was wash-oi (a series of protective maneuvers designed to ward off attacks inline with David Dellinger's practice of nonviolence), many of those practicing in the park were expecting and even welcoming violence. David Baker, a Mobe leader from Detroit, said that passivity in Chicago would get them nowhere. “To remain passive in the face of escalating police brutality is foolish and degrading. The advice used to be that you should give police a flower and say, ‘Hello brother.’ But it didn’t stop the brutality, and people continued to get hurt.” Finding unique ways to avoid injury was on the mind of some of those in the park that afternoon. A young graduate student there to help train Mobe’s marshals for convention week told the New York Times, “We’re still dedicated to peaceful methods, but I can tell you there are some doubts in the movement these days about the old-time nonviolent stance—you know, rolling yourself up in a little ball on your side and getting clubbed. Some of the guys who’ve done that have been very badly hurt. Let’s just say we’re planning more active and mobile forms of self-defense.”

While the park activity continued, a phalanx of uniformed officers, some on motorcycles, watched from nearby. Former cop Eddie Kelso clearly remembers the arrival of the first crowds of protestors. “They actually seemed to appear out of nowhere. I don’t think we were monitoring the bus station, and most probably came in by car, but there they were in the park, sitting in circles, smoking, and I remember them going through their fight sequences; it didn’t look too harmless to me; it looked like they were preparing for a riot and meant to do some harm.”

The sight must have appeared at least a bit ominous as about seventy-five young men and women wash-oi snake-danced in formation across the baseball field with news cameras filming the display. Sun-Times reporter Brian Boyer thought the kids looked like a “football team going through summer practice.” As plainclothes officers moved about the perimeter snapping photographs, Boyer’s colleague Hugh Hough sensed that the young demonstrators meant business. “It was immediately evident that they planned something more than fun and games during next week’s Democratic National Convention. The silent policemen looking on were not amused. Former cop Dennis Pierson recalls, “We were about seventy-five yards away and they were doing those flying kung fu kicks, and we could overhear them as well, saying what they were going to do to us if we tried to arrest them. 'These pigs were going to squeal,' I heard more than once. When I heard that, my hand twitched on my nightstick.”

Adding to the trepidation for police and city officials was the extremely violent Republican National Convention that had just ended in Miami. Snipers had fired on policemen, armored personal carriers were on the streets, and three people lost their lives. “We watched the news reports on TV and it looked bad,” says Orrest Hupka. “The guys were expecting even worse here as the Democrats were the ones in power and were the ones the radicals blamed for the war. The Miami stuff put the force on edge.” Indeed, deputy superintendent of police James Rochford had traveled to Miami to observe security measures and learn how to prepare for convention week in Chicago. Some officers recall that Rochford returned with more than just an insight of convention security techniques. Says Reg Novak, “I heard that he was scared as hell, and that made people nervous for what was going to happen here, because nothing scared that man; so we knew we were in for hell.”

The reports from across the nation were also making police apprehensive. The August 9 edition of the Sun-Times reported that in the previous five weeks, eight of their fellow police officers had been killed and forty-seven wounded in disturbances nationally. Commentators blamed much of the violence during the Miami convention on “outsiders” set on making trouble for the Republican convention. Adding to the mood were ominous reports that outside groups were plotting assassinations. Grand jurors probed rumors of an alleged assassination plot against Democratic candidates, subpoenaing sixteen people, including members of the Youth International Party. Letters to the editor in the Sun-Times warned of violence from the so-called peace demonstrators suggesting that they were little more than “dupes” for “infiltrated Communists.”

There was also reason to be nervous when on the night of Thursday, August 22, Jerome Johnson a seventeen-year-old Native American from Sioux Falls, South Dakota, dressed in hippie garb, was shot and killed by police near Lincoln Park. A pair of detectives had stopped Johnson and another man, eighteen-year-old Bobby Joe Maxwell of Columbia, Tennessee, for possible curfew violations on North Avenue near LaSalle in Old Town. Johnson drew a .32 caliber revolver from a flight bag and fired a shot, narrowly missing one of the officers. “We we’re passing North and LaSalle and stopped to question these two because they might be curfew violators. Maxwell showed us a draft card. The other youngster reached in his flight bag, pulled a pistol and fired one shot,” reported detective John Manley, who, along with fellow officer Frank Szwedo, returned fire on the fleeing Johnson after he “turned around with his gun raised again.” The officers fired three times, striking Johnson; one bullet passed through his heart. Manley was treated in the hospital for powder burns between his chest and left arm from Johnson’s bullet. Officers arrested Maxwell on a weapons charge after police found a ten-inch hunting knife strapped to his chest. For police, the shooting was an unsettling incident only four days before the beginning of the national convention. The force was on edge with the influx of new faces, veteran protestors, and rumors of trouble.

Movement leaders made a last-minute attempt to secure march permits as Mobe, the Yippies, and political activist Allard Lowenstein sued the city in U.S. District Court. On Friday before the convention was to begin, federal Judge William J. Lynch (Daley’s former law partner) ruled that there would be no permits. The only permit that was allowed at all for convention week was granted to Mobe for a rally at the Grant Park band shell for the afternoon of Wednesday, August 28, and that was only granted on Tuesday the 27th, after the convention was already under way. Antiwar leaders including David Dellinger were defiant in the face of the judge’s ruling. “We’ll march with or without a permit,” Dellinger told members of the media. “When those 1,000 persons come here, they will constitute a permit. They are people who are determined to be at the Amphitheater.” The Mobe leader was not interested in holding an alternative rally in Grant Park. Dellinger said that the park was suitable only as a “staging area for the march.”

Police knew that violence with demonstrators was inevitable. “We understood there would be violence and showdowns,” says Carl Moore. “Even though there wasn’t the crowds we expected, a few thousand people congregated where they were not going to be allowed to be after dark, well, hell, it didn’t take a brain surgeon to predict violence.” Most police officers, indeed, expected trouble, as they knew that protestors would not heed the curfew and would try to march on the convention site. Several officers recalled that their district units were nervous on convention eve. Tim Markosky recalls, “We didn’t know what to expect except trouble. You could feel the tenseness among the members, less laughter, or too much laughter; it was not this ’just wait so we can crack some hippie head.‘ It was nothing like that. Nobody was looking forward to a riot.” Officer Frank Froese agrees, but like most officers, he knew that they would be out in force and would do what they had to do for their superiors. “We had our orders. We knew what we were going to do. There were no permits for marches. No one was allowed to be in the parks after 11 P.M. and they were not going to be allowed to march on the convention site and wreck the thing, so we were ready and we mixed it up with them before the convention even started. That’s when we knew it was going to be a long week.”

The same day, Brigadier General Richard T. Dunn told a news conference that the 5,500 members of the Illinois National Guard set to move into Chicago had been given orders to “shoot to kill” if disturbances got out of hand with looting and arson, or because of attacks on police or firemen. Dunn, however, said he hoped his troops would have a “boring week.” The first incident with police took place three days before the start ofthe Convention. On Friday the 23, the Yippies, showing their complete contempt for the political system, nominated their own Democratic candidate: a 145-pound black and white pig dubbed “Pigasus.” The Yippie candidate for president was “released to the public” at the Civic Center Plaza and was promptly “arrested” by police as he was being “interviewed” by waiting journalists. Editor Abe Peck of the underground Chicago paper the Seed told a reporter for the New York Times that after the nomination, they were “going to roast him and eat him. For years, the Democrats have been nominating a pig and then letting the pig devour them. We plan to reverse the process.”

A Yippie calling himself Wrap Sirhan stated that the group had sent President Johnson a telegram requesting Secret Service protection for their four-legged candidate.“ Five Yippies were taken to jail, including Jerry Rubin and Phil Ochs, while the pig for president’s new official residence became the Chicago Humane Society. The Yippies were released after they each posted a $25 bond. ”The only moment of levity between Chicago policemen and the Yippies that week occurred after we were arrested and were in jail and went in to be booked,“ said Rubin, following the convention. ”One of the Chicago policemen came in and shouted out all of our names and then said, ‘You guys are all going to jail for the rest of your lives—the pig squealed on you.’ “ The department had already put Hoffman, Rubin, Krassner, and some of their associates on 24-hour surveillance, sometimes uttering warnings that sounded to Yippie leaders like threats.”

The only real incident of violence on Friday occurred in the evening when a Vietnam veteran assaulted two members of the group Joe and the Fish in a downtown hotel. Those watching national television, however, were seeing the political rhetoric reach an acute level. With Soviet tanks crushing protestors in Prague, Czechoslovakia, some members of the media found the comparisons to the mood in Chicago irresistible. On the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite, commentator Eric Sevareid voiced his frustrations with Daley’s media restrictions. “The city of Chicago runs the city of Prague a close second right now as the world’s least attractive tourist attraction. The Russian soldiers in Prague may feel slightly more frustrated than the Democratic Party delegates, the reporters, and hangers-on in Chicago, but the Russians, at least, have tanks in which to travel from A to B.” The comments prompted Daley’s director of special events, Colonel Jack Riley, to ask, “Who’s Eric Sevareid?” Executive producer for NBC’s convention coverage, George Murray, was even more direct than Sevareid in affixing blame. “Things are getting impossible. There’s no question that the police are obstructing our coverage.” The comments of Sevareid and Murray did not sit well with police or their families. “Those son-of-a-bitches had no right to compare us to the fucking commies,” blasts former cop Jerry Melton. “That’s the way it was even before the convention began; they were against us, so there was no reason to treat them like independent observers.”

All three major networks had complained loudly for days that Daley and his administration were enforcing restrictions that would make it impossible for them to provide adequate convention coverage. On Friday, the issue came to a head when police ordered the network’s mobile units and vans equipped for onsite taping of events away from the convention site and off the streets. CBS News president Richard S. Salant was outraged. “This is one more shocking barrier in the way of an open convention. Open in the sense that the public, the people of America, have every right to see and hear what is newsworthy as close in time to the event as possible.” Police spokesperson Frank Sullivan said that security not censorship was their main concern. “Our first responsibility is to the delegates. The TV trucks would impede the orderly transportation of delegates to and from the hotels.”

By the next afternoon, Saturday, August 24, the first real indication of the trouble that lay ahead appeared. At Lincoln Park, as the first crowds began to assemble, a young college student asked one of the officers where the Yippies were. “Over there,” said the officer. “You can smell them.” The gathering was peaceful, with police watching from the periphery. Poet Allen Ginsberg was holding court in the center of the crowd, encouraging the gathering to join him in chanting “Om, om, om.” The chant, Ginsberg said, had the twin effect of calming and connecting people, enabling them to transcend present circumstances. While the chants went on, plainclothes police officers roamed the grounds looking for trouble, monitoring Yippie leaders, and trying to look inconspicuous. Patrolman Cal Noonan recalls their appearance: “The plainclothes guys were a hoot. They were just cops in casual clothes and there was no way they were fooling anyone. But we were watching them [demonstrators] as closely as we could, we wanted to be everywhere they were, and we were.”

With the realization that gatherers did not have a permit to remain in the park after 11 P.M., tension began to build as afternoon turned to evening. Ginsberg and his group continued chanting until about 10:40 P.M. before rising to lead people out of the park in the hopes of avoiding a confrontation with police. Approximately 1,000 people had already left the area by that time. Ginsberg led all but a couple of hundred out of the park. Encouraged by Yippie leaders and others not to make a stand before the convention even began, the majority of the crowd dissipated prior to the 11 P.M . curfew leaving only about 200 hardcore gatherers. Police soon moved in. With motorcycles in the lead, they cleared the park, and in the process they arrested eleven people for failing to disperse. Although there was little trouble in the park that night, a more surprising development occurred on the streets outside. The bulk of the crowd that had alread moved several blocks away from the park, without provocation, suddenly began to run toward Wells Street—the main street in Old Town-yelling “Peace now! Peace now! Peace now!” Some of the Saturday night throngs, mostly young Chicagoans with both long and short hair-soon joined them. Drivers in their cars honked their horns and displayed the peace sign out their windows. Even with the large crowd in the middle of the street, the assemblage did not rock cars or break windows. Indeed observers described the spontaneous demonstration as a peaceful march of citizens in their own city or a “joyful and exuberant release from the tension of the day.” The crowd moved unmolested by police for ten blocks down the middle ofthe street until officers, apparently caught offguard, caught up to the end ofthe parade to make a small number of arrests. When the bulk of the crowd realized that they had gained the attention of police, some yelled, “Get back on the sidewalk! Don’t give the pigs a chance to bust you! This is only the beginning.” Marchers quickly blended into the evening and into the regular crowds on the sidewalks. The march evaporated as quickly as it began.

The spontaneous march, however, reverberated throughout police ranks. Officer Ronald Lardo remembers it well. “We caught major shit for that, let me tell you. That Old Town shit, well, we heard about that that night and the next day before our shifts began. We were reamed out. The word was that there was not going to be any people marching down the middle of the street anywhere stopping traffic, peaceful or not. Word was it didn’t matter. Disperse everyone, no matter who they were, quick and sure, no screwing around. No Mr.NiceGuy.” Other cops such as Milt Brower, said that the Old Town episode sent shock waves through the department. “We had been hearing for weeks how crowd control was everything, and then before the convention even began, while we were napping on that nice Saturday night, a damn march began right there in the main street, stopping traffic, and the press is there taking photos. I think that the reason shit hit the fan was that one of those photos made its way to someone at city hall, or Daley’s desk, and someone had a fucking conniption, and it went down the food chain. From then on, we were going to be there before they were and if they stepped onto the street we were going to knock them all the way back on or else. We were not going to wait for the crowds to pour in and overwhelm us.”

Given Daley’s extreme precautions, the numbers of protestors in Chicago on convention eve were far from overwhelming. Although Yippie organizers had estimated attracting 10,000 to 15,000 followers to their five-day Festival of Life in Lincoln Park, the numbers averaged only between 8,000 and 10,000 and never eclipsed 10,000 in total. Movement leaders had repeatedly warned people to stay away. Todd Gitlin recalled “Just before the convention opened, I wrote a front-page headline for an eleventh-hour Express Times advance piece on Chicago: ‘If you’re going to Chicago, be sure to wear some armor in your hair.’ Hayden was unhappy about the public foreboding, mine among them, but the warnings piled up.… Most of the movement stayed away.” Indeed, a disbelieving Hayden realized how much Daley’s saber-rattling had set back their efforts. On the Saturday before the convention, Hayden exclaimed, “My God, there’s nobody here.” Given the increase in the numbers of police, army troops, and National Guard units, it had become clear that the forces amassed against demonstrators were somewhat dispro portional. As columnist Mike Royko dryly observed, “Never before had so many feared so much from so few.”

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 49–63 of Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention by Frank Kusch, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2004 by Frank Kusch. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Frank Kusch

Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention

©2004, 224 pages, 11 halftones, 3 maps

Paper $16.00 ISBN: 978-0-226-46503-6 (ISBN-10: 0-226-46503-9)

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Battleground Chicago.

See also:

- An excerpt from Chicago '68 by David Farber

- An excerpt from No One Was Killed: The Democratic National Convention, August 1968 by John Schultz

- An excerpt from The Chicago Conspiracy Trial by John Schultz

- Our catalog of history titles

- Our catalog of books about Chicago

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog