An excerpt from

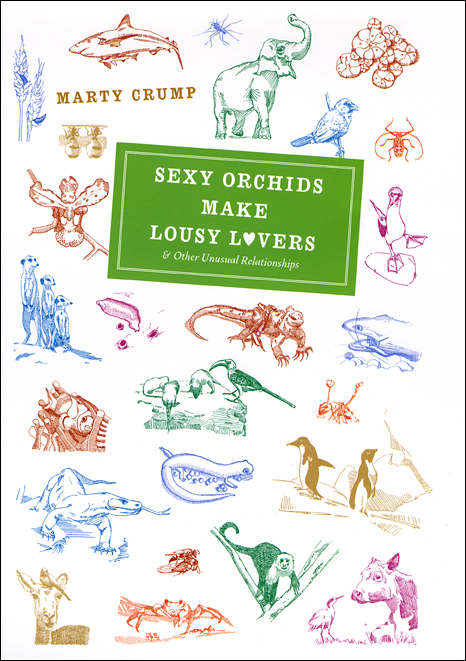

Sexy Orchids Make

Lousy Lovers

& Other Unusual Relationships

Marty Crump

Not Tonight, Honey

Nobody will ever win the battle of the sexes.

There’s too much fraternizing with the enemy.

—Henry Kissinger

We joke that from a reproductive standpoint men are “expendable” because they can contribute to reproduction often and over a long period of time. They’re a dime a dozen. In contrast, females are more “valuable” because they can reproduce only a small number of times in their lives.

Is there any biological basis to the expendable/valuable argument? Yes, and humans aren’t alone in this regard. Bear with me a moment before we get to the stories. One commonly held viewpoint is that sex role is determined largely by initial investment in gametes, or sex cells. Males produce lots of tiny sperm. Females produce few, energy-rich eggs; thus, their initial investment in offspring is much greater than that of males. A male can maximize his paternity potential by mating with as many females as possible. A female, though, often needs only one male per reproductive season to fertilize her eggs. Whereas a female might benefit by choosing her mate carefully, it often pays for a male to sow his wild oats widely. What this means is that males often compete for the limited number of receptive females.

In nature when males try to mate as often as possible and compete with each other for limited encounters while females hold out for the “best” males, the differing goals can lead to conflict between the sexes. Sometimes the conflict involves coercion, manipulation, deceit, and even physical harm by one sex to the other. And the other sex doesn’t just take this lying down. Consider the following non-human examples.

one summer i studied aggressive behavior in variable harlequin frogs (Atelopus varius) in the mountains of Costa Rica. My study site was a forest stream where the frogs congregated on boulders in the water and on the ground nearby. The frogs were active during the day, and as long as I stood or sat quietly, I could watch without disturbing them. Each variable harlequin frog has a unique black-and-yellow color pattern. I took a Polaroid picture of each frog and kept a mug file so that I could recognize individuals.

Like most male frogs, a male variable harlequin climbs onto the larger female and clasps her with his forelimbs in a position called “amplexus.” In most species of frogs, the pair stays in amplexus for a few to 24 hours before the female lays eggs and the male fertilizes them externally. In the variable harlequin, however, the male stays locked in amplexus for days or weeks! Because piggybacking males sit too high off the ground to capture much food, toward the end of the breeding season they become frightfully emaciated. One wonders how these weakened males can still get excited enough to fertilize their mates’ eggs!

Like most male frogs, a male variable harlequin climbs onto the larger female and clasps her with his forelimbs in a position called “amplexus.” In most species of frogs, the pair stays in amplexus for a few to 24 hours before the female lays eggs and the male fertilizes them externally. In the variable harlequin, however, the male stays locked in amplexus for days or weeks! Because piggybacking males sit too high off the ground to capture much food, toward the end of the breeding season they become frightfully emaciated. One wonders how these weakened males can still get excited enough to fertilize their mates’ eggs!

Why might males hang on so long in amplexus? On any given day, the sex ratio of frogs out and about at the stream was strongly skewed toward males. Most of the females were probably hiding in rock crevices. Perhaps once a male encounters a female—during the breeding season, he mounts and hangs on because he might not get another opportunity to mate. But why should a female put up with lugging around a male for days or weeks when there are plenty of males to go around?

One afternoon as I sat on a mossy boulder near the spray zone of a two-foot waterfall, the answer became obvious: Females don’t put up with it. I spotted movement on the rock face: a pair of amplexing harlequin frogs. The female slowly lifted one hind limb, rolled a bit to the opposite side, and tried to dislodge the male. For the next four hours, she worked to shed her piggybacking suitor. She crawled into a crevice and tried to scrape him off by rocking back and forth. When that didn’t work, she crawled back out and bounced up and down like a bucking bronco. The male held tight. A week later I found the same pair on the same rock face. During the 30 minutes I watched them, the pair sat passively. The female might have been too exhausted to fight back, was taking a breather, or was nearly ready to lay eggs.

Over the next few weeks, I watched other females try to dislodge males. In each case where the female was successful, the dislodged male dismounted over the female’s head. Big mistake. Payback time. Each time the female pounced on the male and jumped up and down, pounding his head against the ground or rock with her forelimbs.

Clearly, prolonged amplexus presents a conflict of interest for the sexes. It makes sense that a male should nab a female when he can, but if the female’s eggs are not mature yet, she is stuck lugging around a deadweight for days or weeks. It’s difficult to say who’s winning the battle of the sexes in these harlequin frogs. From what I observed, it was a tie. About half the males hung on. The rest got dumped and stomped on.

So, what does a female gain by attempting to dump a male that has jumped on too soon? One possibility is that by resisting males, females end up with the strongest and most tenacious guys around—great genes to pass on to the kids. Alternatively, male quality might not be involved at all. Perhaps females not yet ready to lay eggs resist amorous males simply to avoid wasting energy lugging them around.

have you ever watched water striders, those long-legged, slender insects that skate on the surface of ponds or slow-moving streams? In many species, males use either their antennae or legs to grasp reluctant females during mating. Once a male grabs a female, he hangs on and she is stuck carrying him—just as in variable harlequin frogs. She skates for the two of them, which costs her 20 percent more energy. Also, because she now skates more slowly and is less agile than when alone, she is both more likely to get eaten and is less efficient hunting for food.

Her defense? Female water striders have antigrasping structures. For example, females of some species have elongated spines that flank their genitalia and discourage unwanted suitors. Females that try to resist grasping males might come out ahead. As with variable harlequin frogs, the females’ eventual partners might be those males strong enough or persistent enough to overcome females’ resistance. Or resisting females might simply live longer and/or find more food.

So, who’s currently winning the arms race in water striders: persistent males or resisting females? In those species where males have exaggerated grasping structures and females have exaggerated antigrasping structures, it may be too close to call. In some species, male grasping structures are stronger than female antigrasping structures, and mating rates are high. Score one for males. In other species where the reverse is true, mating rates are low. Score one for females.

a more extreme example of sexual conflict involves bedbugs. These flat 1/5 - to 1/4-inch-long bugs look remarkably like apple seeds—same color and shape. Unlike most apple seeds, though, human bedbugs make disagreeable houseguests. After dark they crawl out from crevices in bedding and mattresses and gravitate toward warmth and carbon dioxide: sleeping people. They pierce skin and suck blood.

Regardless of how we might feel about the feeding habits of bedbugs, their reproductive habits are fascinating. Males of species with internal fertilization normally insert their reproductive organs into the females’ reproductive tracts during copulation. Not so with bedbugs. They display “traumatic insemination.” Sounds nasty, doesn’t it? It is, from the female’s perspective. A male bedbug mounts the female sideways, grasps her with his legs, curves his abdomen under hers, pierces his dagger-like external genitalia through the underside of her abdominal wall, and ejaculates sperm and fluids into her body cavity. Sperm travel from the female’s blood into storage structures, then on to the ovaries, where the eggs are fertilized. Although the female’s reproductive tract is fully functional, it ends up being used only for laying eggs. You’re probably wondering why. This unusual mating system may have evolved as a way for males to overcome resistant females. It seems that male bedbugs are way ahead of male harlequin frogs and water striders—if you want to look at it that way.

Regardless of how we might feel about the feeding habits of bedbugs, their reproductive habits are fascinating. Males of species with internal fertilization normally insert their reproductive organs into the females’ reproductive tracts during copulation. Not so with bedbugs. They display “traumatic insemination.” Sounds nasty, doesn’t it? It is, from the female’s perspective. A male bedbug mounts the female sideways, grasps her with his legs, curves his abdomen under hers, pierces his dagger-like external genitalia through the underside of her abdominal wall, and ejaculates sperm and fluids into her body cavity. Sperm travel from the female’s blood into storage structures, then on to the ovaries, where the eggs are fertilized. Although the female’s reproductive tract is fully functional, it ends up being used only for laying eggs. You’re probably wondering why. This unusual mating system may have evolved as a way for males to overcome resistant females. It seems that male bedbugs are way ahead of male harlequin frogs and water striders—if you want to look at it that way.

What about the female bedbug’s point of view, though? Can traumatic insemination hurt her? Yes. She might experience blood loss, infection, or an immune reaction to the sperm and fluids introduced into her blood. In addition, wound repair and healing require energy that could be spent on something else, such as foraging for more blood. Females forced to mate repeatedly don’t live as long as less molested females. Is there anything female bedbugs can do to resist males? Like female variable harlequin frogs, females of some kinds of bedbugs vigorously shake males that try to mount them. If successful, the females run away.

Even more remarkable is that females of many advanced species of bedbugs have a secondary reproductive system called the “paragenital system,” which consists of one or both of two parts. The ectospermalege is a region of swollen and often folded tissue centered in the abdominal wall where males would normally try to pierce females. This tissue provides the female with some protection from the stab. The mesospermalege, located underneath the ecotospermalege, is a pocket or sac attached to the inner surface of the abdominal wall. This sac receives the ejaculate if the male succeeds in penetrating. As a point of interest, the human bedbug has both structures. Experiments suggest that these structures reduce the direct costs of piercing trauma and infection by pathogens introduced with the piercing. In an evolutionary sense, females have fought back.

let’s go to some less abusive relationships. Females of some animal species having internal fertilization mate with more than one male to fertilize a cycle of eggs, but some of those presumptive fathers may not sire any of the eggs. In some species, males have a mechanical way of ensuring that their own sperm will indeed hit the jackpot: copulatory (mating) plugs that serve to enforce chastity from then on. In rats, guinea pigs, squirrels, and other rodents, this plug is formed in the female’s vagina by a coagulating substance in the male’s seminal fluid. Males of garter snakes and some other snake species produce copulatory plugs composed of proteins and lipids from their kidneys. They insert these plugs into the females’ cloacae following insemination. Certain insects have ingenious copulatory plugs: their own body parts. After mating, a female biting midge eats her mate, but his genitalia stay lodged in her genital opening and provide a plug that inhibits other males from inseminating her. When a male honeybee catches a virgin queen during her nuptial flight, he too gives his all. His genitalia explode inside the female. Leaving his privates inside to block the queen’s vagina, he falls to the ground and dies.

A copulatory plug might assure paternity for the male, but what good is it for the female? It might prevent her from being hassled by other males, but it might not always be a benefit. What if she were later to come across a “better” mate? Or what if mating with additional males might increase the genetic diversity of her offspring? In species with female promiscuity, there’s often a conflict of interest between the sexes: it’s a male’s advantage to be the only mate, but the gains by engaging in multiple matings—exceptions to the “normal” pattern. In some of these species, females circumvent the copulatory plugs just as amorous medieval maidens might have figured out how to wriggle out of chastity belts.

John Koprowski spied on the sex lives of fox squirrels and eastern gray squirrels on the campus of the University of Kansas. He observed that following copulation, females groomed their genitalia. While cleaning themselves, they often removed copulatory plugs with their incisors. Sometimes the squirrels ate their plugs; sometimes they threw them onto the ground. By removing the plugs, females could later mate with additional males.

It’s to a female honeybee’s advantage to mate multiple times, to store more sperm. But what’s the use of re-mating if she is plugged up with a previous lover’s genitalia? Male honeybees have evolved a way of dislodging their predecessors’ copulatory plugs. This allows a “Johnny-come-lately” male a stab at paternity, but because it also increases the quantity of sperm the female receives, both sexes benefit. Think about it, though. The “Johnny-come-lately” male gains by not having his exploded genitalia removed in turn by a successor, whereas the female gains by having it removed so she can accumulate more sperm. There’s conflict between the sexes again.

So, how does a male honeybee remove another male’s genitalia? If you ever have occasion to examine a male honeybee’s phallus, look for the hairy structure at the tip. That’s what he uses to try to gouge out the previous male’s privates—“try,” because not all attempts are successful. After all, if genitalia-gouging were 100 percent successful, it wouldn’t ever pay for our male to leave behind his own privates unless he could be sure that he was the “Johnny-come-latest!”

The battle of the sexes is a dynamic evolutionary process. At a given point in time, it might appear that one sex is ahead in the running battle. But give the other sex time, and the odds will probably even out. Henry Kissinger was right. Neither males nor females will win the battle of the sexes. We need each other—even though at times the opposite sex might act like a different species.

Women are from Venus; men are from Mars—or so we thought in middle school. Men’s and women’s physiologies and anatomies are regulated by different chemicals. Our brains are wired a little differently. We often view the world—and life itself—from different perspectives. Perhaps we need each other to fill in the gaps, to feel complete. So try to understand when he forgets your anniversary. Or when she spends an hour primping before going out to dinner. Of course, there are many exceptions to these stereotypes. To begin with, not all males are promiscuous and not all females are coy. Once we accept the basic differences between men and women, though, we find beauty and mystery in our relationships. Maybe that’s why we keep fraternizing with the enemy. In humorist Dave Barry’s words:

What Women Want: To be loved, to be listened to, to be desired, to be respected, to be needed, to be trusted, and sometimes, just to be held. What Men Want: Tickets for the World Series.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 2–8 of Sexy Orchids Make Lousy Lovers: & Other Unusual Relationships by Marty Crump, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2009 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Marty Crump

Sexy Orchids Make Lousy Lovers: & Other Unusual Relationships

Illustrations by Alan Crump

©2009, 232 pages, 120 line drawings

Cloth $25.00 ISBN: 9780226121857For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Sexy Orchids Make Lousy Lovers: & Other Unusual Relationships.

See also:

- An excerpt from Marty Crump’s Headless Males Make Great Lovers: And Other Unusual Natural Histories

- An excerpt from Marty Crump’s In Search of the Golden Frog

- Our catalog of books in biology

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog