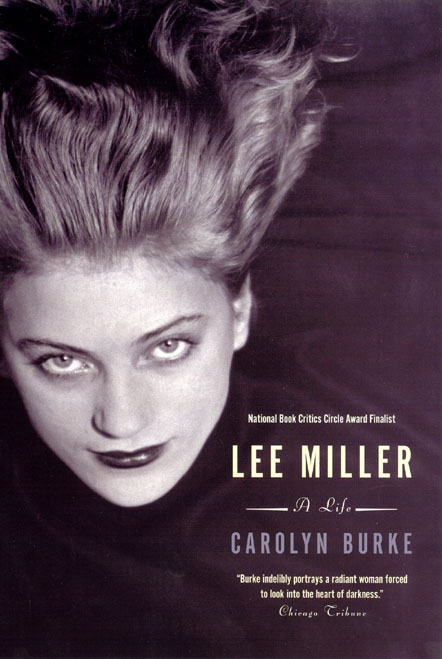

An excerpt from

Lee Miller

A Life

Carolyn Burke

Covering the War in France

On June 6, 1944, D-day, the Allies invaded Normandy. After photographing the onslaught from a U. S. Navy ship, Dave [Scherman, a Life photographer] returned to London twenty-four hours later to find Lee preparing her own invasion. This was the work she wanted. She did not intend to miss her chance.

Nearly sixty years later, it is hard to imagine the constraints under which women journalists operated, even as they were becoming glamorous figures in popular culture. Life publicized the exploits of [Margaret] Bourke-White, who posed like a film star in her flight gear after gaining permission to fly with the air force. Hollywood churned out movies about “girl photographers”—romances in which the heroine’s calling placed her at odds with the promptings of her heart. But newsworthy female journalists knew that they were unlikely to see combat. SHAEF [Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force] protocol did not allow them to travel alone or visit press camps in a theater of operations. Nor were they assigned jeeps and drivers. As if they too belonged to an auxiliary corps, they were to stay behind the lines with the nurses. On D-day, Lee and her women colleagues were told that they must remain in England and file their stories from the invasion bases in the south.

During the next weeks, Lee suffered through several rounds of vaccinations and, with the rest of London, coped with the new German missiles—the pilotless V-1s known as robots, doodlebugs, or buzz bombs. People ducked for cover at the sound of the V-1, which resembled the drone of a badly maintained motorcycle. Since it was hard to tell the start of a raid from its conclusion, nerves soon frayed from the sirens’ constant wail. The weather—cold wind and driving rain—added to the strain. Lee coped by drinking the gin that came in the mail from Roland [Penrose]. “[It] saved my sanity,” she told him on August 2. “See if you can do a deal for further supplies.”

In July, SHAEF ruled that women journalists could report on the battle for France as it unfolded rather than return to London after each trip. Mary Welsh went on an official tour to cover the Medical Corps; on her return to the Dorchester, she related her experience to Hemingway, who was preparing to leave for France as Collier’s war correspondent, [Martha] Gellhorn having flown to Italy to cover the fighting. Iris Carpenter resented being assigned to an Allied hospital, but found that ambulances could be exciting when bombs fell all around her, shattering her eardrums. It was useful to have the backing of a major newspaper, a general, or both: Helen Kirkpatrick, the London bureau chief for the Chicago Daily News convinced Ike to send her to France.

While it was not clear that Brogue [British Vogue] needed a war correspondent, Audrey Withers tried to make each issue topical. “It was all very well encouraging ourselves with the conventional patter about keeping up morale,” she recalled, “but magazines—unlike books—are essentially about the here and now. And this was wartime.” Toward the end of July, as the Allies struggled to take the German strongholds along the Normandy coast , she sent Lee to report on the American nurses’ postinvasion duties.

Lee’s sense of the trip’s strangeness pervades her published account: “As we flew into sight of France I swallowed hard on what were trying to be tears, and remembered a movie actress kissing a handful of earth. My self-conscious analysis was forgotten in greedily studying the soft, gray-skied panorama of nearly a thousand square miles of France—of freed France.… Cherbourg was a misty bend far to the right, and ahead three planes were returning from dropping the bombs which made towering columns of smoke. That was the front.”

The sensuous particularity of this first paragraph would characterize her dispatches, along with her ability to focus the story with her photographer’s eye. She regularly saw what others missed. “When you think that every situation she covered was completely outside her previous experience,” Audrey reflected, “it makes the sheer professionalism of her text even more remarkable.” In some ways Lee was winging it, inspired by Ed Murrow’s seat-of-the pants approach. Yet the many drafts in her archive attest to the care she took to get the story right. Reading these different versions, one is struck by her ability to go to the heart of the matter.

After landing, Lee took quick, painterly notes while her convoy drove to the 44th Evacuation Hospital, near Omaha Beach, and later, to a hospital near the front. France looked familiar—“the trees were the same with little pantaloons like eagles, and the walled farms, the austere Norman architecture.” Yet it was also full of strange juxtapositions. Strands of barbed wire “looped into each other like filigree.” A skull and cross bones on a board in a hedge barred the way to fields of poppies, daisies, and landmines. Signs at crossroads bearing American code names—Missouri Charlie, Mahogany Red, Java Blue—stood beside those of Norman villages.

Camera around her neck and noteboook in hand, she toured the tents where the wounded awaited treatment. Following the same pattern as in photo shoots, she surveyed the scene from a distance, then moved in for close-ups: “In the shock ward they are limp and flat under brown blankets, some with plasma flasks dripping drops of life into an outstretched splintered arm, another sufficiently recovered to smoke or chat to see if he’s real. A doctor and nurse are busy on the next with oxygen and plasma. The rest are sleeping or staring at the dark brown canvas—patient, waiting and gathering strength for multiple operations on unorthodox wounds.”

Lee zeroed in on one of the most unorthodox: a man whose entire body was swathed in bandages, with slits for his eyes, nose, and mouth. “A bad burns case asked me to take his picture as he wanted to see how funny he looked,” she wrote. Complying uneasily with his request (“It was pretty grim and I didn’t focus good”), she showed the man as a grinning white mask. The “grimness” of the case is betrayed in the shot’s blurred focus—a trace of the shock she felt in this first encounter with a badly damaged body.

Moments later, a surgical patient watched her take his picture. “In the chiaroscuro of khaki and white I was reminded of Hieronymus Bosch’s painting 'The Carrying of the Cross,'” she wrote. “I didn’t know that he was already asleep with sodium pentothal when they started on his other arm. I had turned away for fear my face would betray to him what I had seen.” That day, she learned that one could photograph horror, but at a cost.

Arriving at a field hospital closer to the front, she focused instead on technique, the use of “the magic life-savers”—sulfa drugs, penicillin, and blood transfusions. Yet even then, individual cases suggested larger themes. Others felt the need to record the mayhem, she noted: “Without looking up from his snipping a surgeon asked me to write down for him what exposure he should use if he wanted to take a detailed picture of an operation in that contrast of white towels, concentrated light and deep shadows.” The next day, watching a doctor “with a Raphael-like face” treat a badly wounded man, Lee saw the scene in her mind’s eye as an archetype of compassion.

Her response to suffering often troubled her. She sympathized with the hardworking American nurses whom she photographed off-duty. But trying to sleep that night in a tent recently vacated by enemy staff, she recalled, “I entangled myself with distaste in the blankets of the German nurses”—an intimacy that disturbed her as much as the gunfire. Then, watching German and American doctors work side by side, she wrote, “I stiffened every time I saw a German, and… resented my heart softening involuntarily toward German wounded.”

On the road to the collection station, where cases were assigned to treatment, she spotted many odd sights—behind the Utah Beach hospital, “rolypoly balloons with cross-lacing on their stomachs like old-fashioned corsets,” children in pinafores and soldiers’ caps directing traffic,” fields with whole, transplanted trees sharpened into spikes against our landings”—some of which she captured on film. But the bulk of her images from this first trip show the most urgent cases, the “dirty, disheveled, stricken figures” and those who cared for them.

Before returning to London, Lee posed for her own portrait. In it, she stands with her hand at heart level, just below her war correspondent badge, and wears a metal helmet borrowed from Don Sykes, the army photographer who took the picture. (His customized headgear had a striped visor that had been cut away so he could wear it to shoot movies. “Sykes had painted on the stripes for fun,” she noted.) Though Lee’s expression belies thoughts of “fun,” U. S. Vogue ran this portrait in her “U.S.A. Tent Hospital in France” on September 15, along with her shots of medics at work, the bad burn case, and the trees with pantaloons. A helmeted Lee also appeared in ads announcing, “VOGUE has its own reporter with the United States Army in France”—as if the portrait’s mix of decorum and eccentricity conveyed her unique perspective.

This story also appeared in the September Brogue as “Unarmed Warriors.” Publishing Lee’s reportage was “the most exciting journalistic experience of my war, “Audrey declared, and a source of pride for the entire staff: “We were the last people one could conceive having this type of article, it seemed so incongruous in our pages of glossy fashion.” Lee’s article not only thrust the magazine into the here and now; it showed that high gloss and seriousness were not antithetical.

Throughout the summer, V-1s bombarded London. Reports of a crisis in Germany after a failed attempt on Hitler’s life filtered back, but there was little optimism about the war’s ending soon. In August, Lee wrangled an assignment in Brittany—to cover the U.S. Army’s efforts to maintain order in Saint-Malo after its liberation from the Germans, another behind-the-lines job. She crossed the Channel on an LST, one of the large landing ships that had been ferrying troops to France since D-day. During the trip, she beat the captain at poker and talked with the crew about their adventures. Her own began when the LST ran aground at Omaha Beach and a sailor carried her ashore.

On her way to Brittany, Lee saw the devastation at Isigny, Carentan, and Sainte-Mére-Eglise. She reached Saint-Malo on August 13 to learn that, contrary to intelligence reports, the town had not been secured. The 83rd Infantry Division of the Third Army had arrived there a few days earlier to find minefields, antitank devices, and rows of steel gates meant to block their advance. The Germans, under Colonel Von Aulock, still held the heavily fortified citadel at the top of the bay, where they commanded positions around the port. In old Saint-Malo, the infantrymen who came in after the tanks were battling house to house with German snipers.

The head of the division’s Civil Affairs unit (CA) took Lee to a hospital where U.S. medics were spicing their C rations with German herbs, then to their post at the once chic Hôtel des Ambassadeurs . “The wicker furniture tried to look gay and brave under the burden of machine guns and hand grenades,” Lee noted. “Instead of a chattering crowd of brightly-dressed aperitif-drinkers, there were a few tired soldiers.” From a window facing the port, Lee shot views of the old city, the citadel, and the Grand Bey fortress. Amused to find a pair of GIs artillery spotting from a bed in the honeymoon suite, she took their picture—an action shot in which the cold gleam of their guns contrasts with the decorative curves of the window rail.

For the next five days, while the Americans attacked the enemy’s positions, Lee had Saint-Malo to her self. “I had the clothes I was standing in, a couple of dozen films, and an eiderdown blanket roll,” she wrote. “I was the only photographer for miles around and I now owned a private war.” After crowds of panicky French prisoners left the citadel during a truce, she helped the CA keep order: “Kept busy interpreting, consoling and calming people—I forgot mostly to take pictures.” She watched mangy pets escaping, women taking morphine for hysteria, “a tottering old couple with no shoes, an indignant dame in black taffeta … a pair of pixie twins, exactly like the little imps at the bottom of the Sistine Madonna”—whom she photographed picnicking in the midst of chaos.

That night, Lee slept well despite the bed bugs. In the morning, she washed in her helmet and ate K rations. Nothing in this life resembled her old one. The urgency of the tasks at hand drew on her gift for meeting events as they arose; the excitement of combat fired her imagination. Screening female civilians for the CA, she talked to a female collaborator who begged for protection against the patriots who were punishing women like herself by shaving their heads. Another collaborator posed for Lee with her children. They stared at her with “big sullen eyes.… They were neither timid nor tough,” she wrote, “and I felt like vomiting.” There was no way to observe with detachment.

To report the facts, the number of bombs deployed and targets damaged, she needed to get close to the action. Major John Speedie, the 329th Regiment’s hand some commander, took her on a tour of observation posts. In one, the sun streamed through the floor-length windows, making it hard for her not to be seen by the Germans (who were only nine hundred yards away), “especially with such shiny things as binoculars.” At another post, in the Hôtel Victoria, she lay on the floor to watch the artillery, her binoculars in the shadows. The GIs were pleased to see her, she thought, “mostly because I was an American woman, partly because I was a journalist and they wanted to be in the papers.”

That evening, Lee moved to a nearby CA office with a phone connection to military command. “They are cooking up the final assault on the citadel,” she scribbled in a note to Roland. “I’m going down to an OP inside the bomblines—to watch and take pictures,—naturally I’m a bit nervous as it’ll be 200 pounders from the air—ours—I know nothing will happen to me as I know our life is going on together—for ever—I’m not being mystic, I just know—and love you.” Lee’s account of the assault brims with the sort of details that animate her photographs. A company files past, “ready to go into action, grenades hanging on their lapels like Cartier clips.” The next section conveys her excitement as the planes arrive:

We heard them swelling the air like I’ve heard them vibrating over England on some such mission. This time they were bringing their bombs to the crouching stone work 700 yards away. They were on time—bombs away—a sickly death rattle as they straightened themselves out and plunged into the citadel—deadly hit—for a moment I could see where and how—then it was swallowed up in smoke.

Lee photographed this explosion not knowing that she had captured the Americans’ first use of napalm. (Most of her shots were confiscated by the censors.) In one, in which the gaze passes through an inner frame formed by the curtain and railing, theme and composition merge. The contrast between the patterned foreground and the explosion catches the release of energy at the decisive moment.

Lee followed the GIs’ ascent to the fort as if she were one of them. “I projected myself into their struggle,” she wrote, “my arms and legs aching and cramped. The first man scrambled over the sharp edge, went along a bit, and turned back to give a hand in hauling up the others.… It was awesome and marrow freezing.” But Von Aulock wouldn’t surrender. At headquarters, “everyone was sullen, silent, and aching,” including her. Before Saint-Malo, she had been a partisan observer. Now she was experiencing the war viscerally.

Later that day, when taking cover during a burst of gunfire, Lee stepped into one of the town’s underground vaults, which by then “stank with death and sour misery.” What follows gives a precise sense of war’s horror: “I sheltered in a Kraut dugout, squatting under the ramparts. My heel ground into a dead, detached hand, and I cursed the Germans for the sordid ugly destruction they had conjured up in this once beautiful town.… I picked up the hand and hurled it across the street and ran back the way I’d come, bruising my feet and crashing in the unsteady piles of stone and slipping in blood. Christ, it was awful.”

The GIs who rushed up a moment later were a benison. They joked and laughed with her, “asking me to talk American.” Lee’s spirits revived when they unearthed supplies in a nearby wine cellar (“bin after bin of sauterne, vouvray, magnums of champagne, Bordeaux, Burgundy”). She chose sweet wine for the soldiers, then joined Major Speedie and the officers at the hotel: “He opened a bottle of champage, aiming the cork at a helmet about as accurately as the bombers had done on the fort, and we drank from crystal glasses which I had polished on a bed spread.” From this point on the personal and public sides of war would be intertwined in her dispatches.

Dave Scherman turned up in Saint-Malo on August 17. After covering the battle from nearby, he wanted to see the results. Some of the most unexpected were the changes in Lee. She looked like “an unmade, unwashed bed” in her olive drabs and boots, he recalled. He photographed her seated on rubble while displaying her good profile, and beside a steel pillbox, while two soldiers from the 83rd peer at their tired, squinting mascot. Dave and Lee made plans to pool their shots, sending some of hers to John Morris and his shots of her to Audrey Withers.

When they reached the Hôtel de l’Univers, the best vantage point for the next assault, white flags appeared. Von Aulock had surrendered. They rushed to see the Germans emerge from their stronghold. The first to appear, a tall, erect man wearing gray gloves, a camouflage coat, and a monocle, was Von Aulock. As Lee ran to take his picture, he hid his face and cursed—he could not bear to have his defeat witnessed by a woman. “I kept scrambling on in front, turning around to take another shot of him,” she wrote. It was a small victory, but an ambiguous one. She empathized with the man in spite of herself: he “seemed awfully thin under his clothes.”

As Lee moved closer to the Germans with another group of GIs, those who looked carefully were amazed to find a woman among the cameramen. “She looked tired; she was covered with dust and dirt but she kept on taking pictures,” one soldier recalled. (In Lee’s shot of this scene, a German smiles at her, and the GIs watch without hostility, pleased that the battle is over.) When she saw Von Aulock later, his dignity restored after a change into uniform, she photographed him again from a respectful distance.

Her own dignity was deflated a few days later when SHAEF exiled her to Rennes after the news reached headquarters that she had been in the combat zone. (A memorandum dated August 20 recommends that henceforth “No female correspondent be permitted to enter forward area under any circumstances.” ) Lee moved into the Hôtel Nemours, U. S. press headquarters, where Dave joined her. She spent the week “in the doghouse for having scooped my battle,” she told Audrey. “I’m mad about the 83rd Division,” she went on. Her application to be attached to them had been turned down, but soon, she added, “I plan to rejoin them.”

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 221-28 of Lee Miller: A Life by Carolyn Burke, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2005 by Carolyn Burke. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Carolyn Burke

Lee Miller: A Life

©2005, 446 pages, 82 halftones

Paper $18.00 ISBN: 978-0-226-08067-3 (ISBN-10: 0-226-08067-6)

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Lee Miller: A Life.

See also:

- Our catalog of art and photography titles

- Our catalog of biography and autobiography titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog