Madera was heavy. I grabbed him by the armpits and went backwards down the stairs to the laboratory. His feet bounced from tread to tread in a staccato rhythm that matched my own unsteady descent, thumping and banging around the narrow stairwell. Our shadows danced on the walls. Blood was still flowing, all sticky, seeping from the soaking wet towel, rapidly forming drips on the silk lapels, then disappearing into the folds of the jacket, like trails of slightly glinting snot side-tracked by the slightest roughness in the fabric, sometimes accumulating into drops that fell to the floor and exploded into star-shaped stains. I let him slump at the bottom of the stairs, right next to the laboratory door, and then went back up to fetch the razor and to mop up the bloodstains before Otto returned. But Otto came in by the other door at almost the same time as I did. He looked at me uncomprehendingly. I beat a retreat, ran down the stairs, and shut myself in the laboratory. I padlocked the door and jammed the wardrobe up against it. He came down a few minutes later, tried to force the door open, to no avail, then went back upstairs, dragging Madera behind him. I reinforced the door with the easel. He called out to me. He fired at the door twice with his revolver.

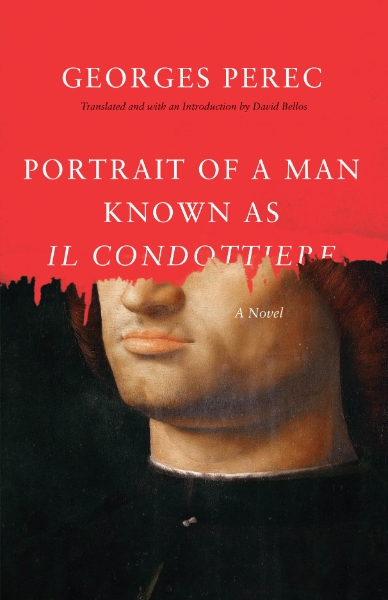

You see, maybe you told yourself it would be easy. Nobody in the house, no-one round and about. If Otto hadn’t come back so soon, where would you be? You don’t know, you’re here. In the same laboratory as ever, and nothing’s changed, or almost nothing. Madera is dead. So what? You are still in the same underground studio, it’s just a bit less tidy and bit less clean. The same light of day seeps through the basement window. The Condottiere, crucified on his easel . . .

He had looked all around. It was the same office—the same glass table-top, the same telephone, the same calendar on its chrome-plated steel base. It still had the stark orderliness and uncluttered iciness of an intentionally cold style, with strictly matching colours—dark green carpet, mauve leather armchairs, light brown wall covering—giving a sense of discreet impersonality with its large metal filing cabinets . . . But all of a sudden the flabby mass of Madera’s body seemed grotesque, like a wrong note, something incoherent, anachronistic . . . He’d slipped off his chair and was lying on his back with his eyes half-closed and his slightly parted lips stuck in an expression of idiotic stupor enhanced by the dull gleam of a gold tooth. Blood streamed from his cut throat in thick spurts and trickled onto the floor, gradually soaking into the carpet, making an ill-defined, blackish stain that grew ever larger around his head, around his face whose whiteness had long seemed rather fishy, a warm, living, animal stain slowly taking possession of the room, as if the walls were already soaked through with it, as if the orderliness and strictness had already been overturned, abolished, pillaged, as if nothing more existed beyond the radiating stain and the obscene and ridiculous heap on the floor, the corpse, fulfilled, multiplied, made infinite . . .

Why? Why had he said that sentence: “I don’t think that’ll be a problem”? He tries to recall the precise tone of Madera’s voice, the timbre that had taken him by surprise the first time he’d heard it, that slight lisp, its faintly hesitant intonation, the almost imperceptible limp in his words, as if he were stumbling— almost tripping—as if he were permanently afraid of making a mistake. I don’t think. What nationality? Spanish? South American? Accent? Put on? Tricky. No. Simpler than that: he rolled his rs in the back of his throat. Or perhaps he was just a bit hoarse? He can see him coming towards him with outstretched hand: “Gaspard—that’s what I should call you, isn’t it?—I’m truly delighted to make your acquaintance.” So what? It didn’t mean much to him. What was he doing here? What did the man want of him? Rufus hadn’t warned him . . .

People always make mistakes. They think things will work out, will go on as per normal. But you never can tell. It’s so easy to delude yourself. What do you want, then? An oil painting? You want a top-of-the-range Renaissance piece? Can do. Why not a Portrait of a Young Man, for instance . . .

A flabby, slightly over-handsome face. His tie. “Rufus has told me a lot about you.” So what? Big deal! You should have paid attention, you should have been wary . . . A man you didn’t know from Adam or Eve . . . But you rushed headlong to accept the opportunity. It was too easy. And now. Well, now . . .

This is where it had got him. He did the sums in his head: all that had been spent setting up the laboratory, including the cost of materials and reproductions—photographs, enlargements, X-ray images, images seen through Wood’s lamp and with sideillumination—and the spotlights, the tour of European art galleries, upkeep . . . a fantastic outlay for a farcical conclusion . . . But what was comical about his idiotic incarceration? He was at his desk as if nothing had happened . . . That was yesterday . . . But upstairs there was Madera’s corpse in a puddle of blood . . . and Otto’s heavy footsteps as he paced up and down keeping guard. All that to get to this! Where would he be now if . . . He thinks of the sunny Balearic Islands—it would have taken just a wave of his hand a year and half before—Geneviève would be at his side . . . the beach, the setting sun . . . a picture postcard scene . . . Is this where it all comes to a full stop?

Now he recalled every move he’d made. He’d just lit a cigarette, he was standing with one hand on the table, with his weight on one hip. He was looking at the Portrait of a Man. Then he’d stubbed out his cigarette quickly and his left hand had swept over the table, stopped, gripped a piece of cloth, and crumpled it tight—an old handkerchief used as a brush-rag. Everything was hazy. He was putting ever more of his weight onto the table without letting the Condottiere out of his sight. Days and days of useless effort? It was as if his weariness had given way to the anger rising in him, step by certain step. He was crushing the fabric in his hand and his nails had scored the wooden table-top. He had pulled himself up, gone to his work bench, rummaged among his tools . . .

A black sheath made of hardened leather. An ebony handle. A shining blade. He had raised it to the light and checked the cutting edge. What had he been thinking of? He’d felt as if there was nothing in the world apart from that anger and that weariness . . . He’d flopped into the armchair, put his head in his hands, with the razor scarcely a few inches from his eyes, set off clearly and sharply by the dangerously smooth surface of the Condottiere’s doublet. A single movement and then curtains . . . One thrust would be enough . . . His arm raised, the glint of the blade . . . a single movement . . . he would approach slowly and the carpet would muffle the sound of his steps, he would steal up on Madera from behind . . .

A quarter of an hour had gone by, maybe. Why did he have an impression of distant gestures? Had he forgotten? Where was he? He’d been upstairs. He’d come back down. Madera was dead. Otto was keeping guard. What now? Otto was going to phone Rufus, Rufus would come. And then? What if Otto couldn’t get hold of Rufus? Where was Rufus? That’s what it all hung on. On this stupid what-if. If Rufus came, he would die, and if Otto didn’t get hold of Rufus, he would live. How much longer? Otto had a weapon. The skylight was too high and too small. Would Otto fall asleep? Does a man on guard need to sleep? . . .

He was going to die. The thought of it comforted him like a promise. He was alive, he was going to be dead. Then what?

Leonardo is dead, Antonello is dead, and I’m not feeling too well myself. A stupid death. A victim of circumstance. Struck down by bad luck, a wrong move, a mistake. Convicted in absentia. By unanimous decision with one abstention—which one?—he was sentenced to die like a rat in a cellar, under a dozen unfeeling eyes—the side lights and X-ray lamps purchased at outrageous prices from the laboratory at the Louvre—sentenced to death for murder by virtue of that good old moral legend of the eye, the tooth and the turn of the wheel—Achilles’ wheel—death is the beginning of the life of the mind—sentenced to die because of a combination of circumstances, an incoherent conjunction of trivial events . . . Across the globe there were wires and submarine cables . . . Hello, Paris, this is Dreux, hold the line, we’re connecting to Dampierre. Hello, Dampierre, Paris calling. You can talk now. Who could have imagined those peaceable operators with their earpieces becoming implacable executioners . . . Hello, Monsieur Koenig, Otto speaking, Madera has just died . . .

In the dark of night the Porsche will leap forward with its headlights spitting fire like dragons. There will be no accident. In the middle of the night they will come and get him . . .

And then? What the hell does it matter to you? They’ll come and get you. Next? Slump into an armchair and stare long and hard until death overtakes into the eyes of the tall joker with the shiv, the ineffable Condottiere. Responsible or not responsible? Guilty or not guilty? I’m not guilty, you’ll scream when they drag you up to the guillotine. We’ll soon see about that, says the executioner. And down the blade comes with a clunk. Curtains. Self-evident justice. Isn’t that obvious? Isn’t it normal? Why should there be any other way out?

Copyright notice: An excerpt from Portrait of a Man Known as Il Condottiere by Georges Perec, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2015 by University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)