Ten Contested Boundaries

by Mark Monmonier

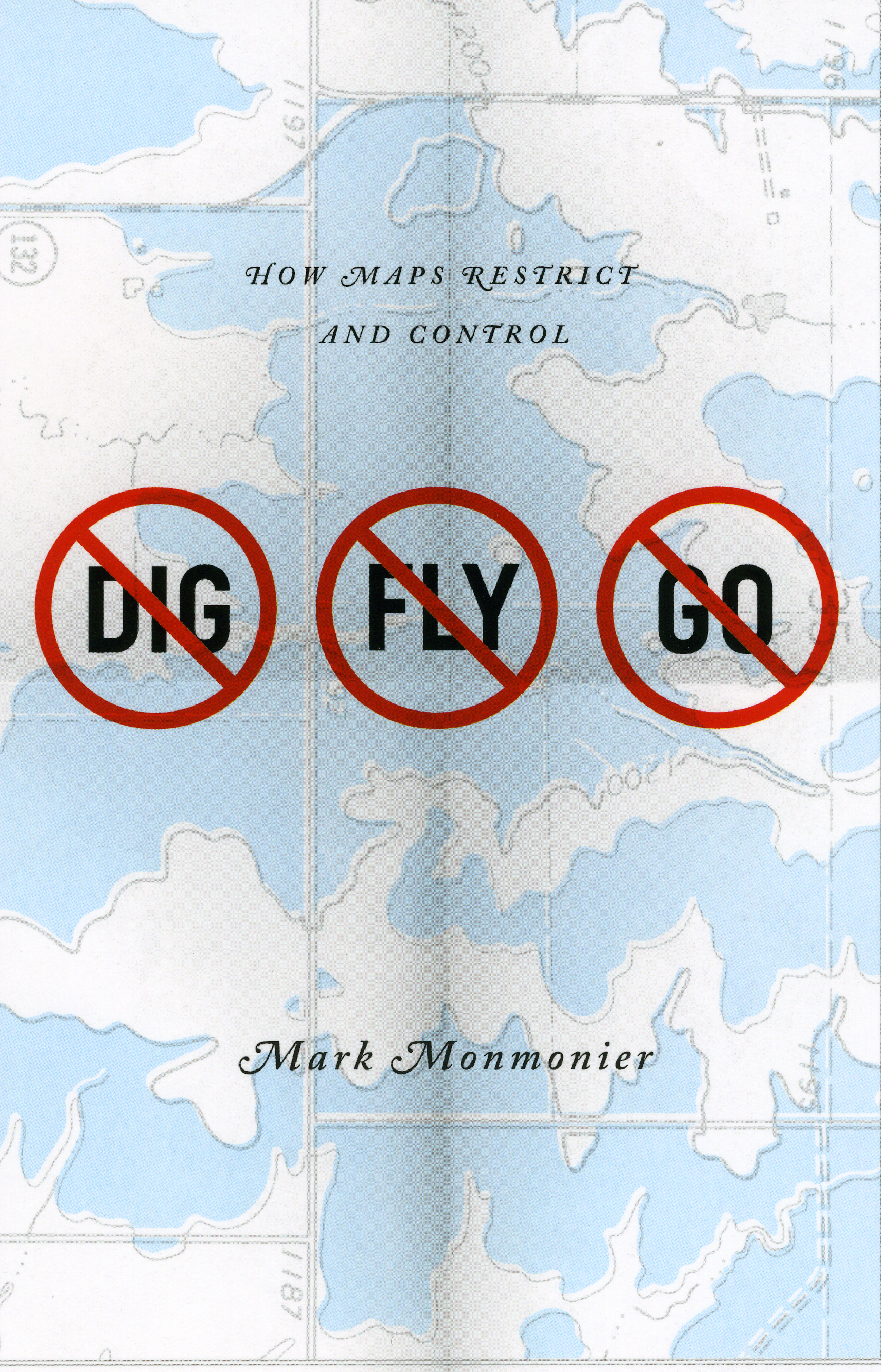

author of No Dig, No Fly, No Go

Boundary lines on maps affect governments and individuals in diverse ways, directly and indirectly. The following list of contentious types of boundaries runs from global to local impacts and notes one example for each type.

- National boundaries. Lines on world or regional political maps raise issues of national sovereignty, including overlapping historical claims, while close analysis highlights the cost of restricting movement and the difficulty of demarcating lines of separation with monuments or physical barriers. Example: Israel – West Bank, including “No Man’s Land,” the “settlements,” Israel’s “security fence,” and the issue of where to draw the line for a “two-state solution.”

- Colonial boundaries. Delineated for the convenience of the colonizers, colonial boundaries persist long after independence, often with tragic results for hostile tribes lumped together within a new national border. Examples include Angola, Nigeria, and the Congo.

- Sector boundaries. Meridians anchored by national territory or colonial outposts and extended toward the South Pole offer a convenient way to claim a slice of Antarctica, and similar boundaries have been proposed in the Arctic as well. Example: Argentina’s persistent claim to an Antarctic sector, which overlaps cartographically similar claims by Britain and Chile, led to a military confrontation with Britain in 1982 over the Falkland Islands / Islas Malvinas.

- EEZs (Exclusive Economic Zones). The twentieth century witnessed increased national encroachment onto the sea floor as coastal territory was extended outward and seabed rights were apportioned into 200-nautical mile EEZs—Japan and the United States are now neighbors. Example: United Nations rules stretched the EEZ concept further to allow claims on the continental shelf, raising questions about the meaning and extent of the continental shelf. Example: Russia’s recent assertion of rights to a large slice of the Arctic seabed—a claim extended even farther, all the way to the North Pole, by sector boundaries.

- Ambulatory boundaries. Temporarily convenient boundaries, used to divide territories ranging in scale from sovereign states to rural property, have been anchored to rivers, some of which shift course, slowly or gradually. Administration and access can suffer significantly unless the boundary is relocated to reflect the river’s new position. Example: the contentious international border separating El Paso, Texas from Juarez, Mexico was reconfigured by treaty, after a lengthy process, to the benefit of both countries.

- State boundaries. In partitioning economically homogeneous regions and large metropolitan areas, state boundaries are often geographic dinosaurs. More rational configurations of state boundaries are often obvious, but constitutional constraints make change unlikely—short of losing a major war, the United States is stuck with its current state boundaries. Example: metropolitan New York, parts of which are administered by Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York State.

Election districts. Subject to change every decennial census, electoral boundaries are often reconfigured to protect a favored incumbent, enhance the leverage of the party in power, and waste the votes of political minorities. Example: New York City’s Bullwinkle District, a highly irregular boundary that invited media scorn and a public backlash in the early 1990s. - Municipal boundaries. City boundaries can offer city services like water and sewer connections, impose added taxes, and give a particular racial or ethnic group a stronger voice in local government. Municipal annexation is easy in some states, difficult in others. Protective incorporation is sometimes used to avoid being swallowed by an aggressively expanding urban neighbor. Example: Tuskegee, AL, where the city boundary was cleverly contracted in the late 1950s—unconstitutionally—to disenfranchise a threateningly assertive racial majority, and expanded decades later to lasso commercial property near a major highway.

- Property boundaries encumbered by a right-of-way, an easement, or an encroachment that a court could sanction as “adverse possession.” A real estate parcel’s complex history might restrict the current owner’s freedom to develop the land. Example: the Munger Right-of-Way, as litigated before the Florida Supreme Court in Enos v. Casey Mountain, Inc.

- Zoning boundaries. Intended to promote aesthetic landscapes and preserve property values, zoning laws not only limit land use but control location, height, and overall appearance of structures erected on a parcel. The courts become involved when zoning laws conflict with other rights, most notably the First Amendment’s protection of “free speech,” which required some jurisdictions to fine-tune their restrictions on strip clubs and adult bookstores. Zoning can be particularly troublesome when a city or town banishes adult-use ones, landfills, or other objectionable activity to its periphery. Example: The adult-use district in the Town of Cicero, New York.

Borrowed boundaries, devised for one purpose but adopted for something else, are a wider reflection of restrictive cartography. Perhaps the best example is the ZIP Code area, intended to expedite mail delivery, but used to set car insurance rates, target advertising, or discriminate against residents of poor neighborhoods.

![]()

Copyright notice: A web feature for No Dig, No Fly, No Go: How Maps Restrict and Control by Mark Monmonier, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2010 by Mark Monmonier. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press.

Mark Monmonier

No Dig, No Fly, No Go

©2010, 242 pages

Cloth $65.00 ISBN: 9780226534688

Paper $18.00 ISBN: 9780226534688

Also available as an e-book

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for No Dig, No Fly, No Go.

See also:

- All books by Mark Monmonier

- Our catalog of cartography and geography titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog