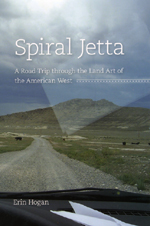

An Interview with

Erin Hogan

author of Spiral Jetta: A Road Trip through the Land Art of the American West

Question: Spiral Jetta is as much a book about solo travel as it is about the Land Art that you visited. You contemplated this 3,000-mile excursion vaguely for a long time—was there a single moment when you finally thought, “Yes, I'm going to do this!”? If so, what triggered it?

Erin Hogan: There wasn’t a single moment that I decided to do this. In fact, I always knew if I ever had an epiphany about my trip, it would be a resounding “No! There is absolutely no way I am going to do this!” So, to make it impossible for me to back out of my own trip, I told everyone I knew that I was going to do it. It was like an insurance policy. Once I told people I was doing it, I more or less had to go, because people were asking “When are you going to take that trip?” Thus I was forced to come up with an answer and then leave at whatever made-up time I had said I would.

Q: All these monumental works tend to get grouped together under the name of Land Art. Do you think that is a sensible way of thinking about them, or does the variation within the group require a more nuanced approach to categorization?

Hogan: I am a fan of categories. There are exceptions and variations in every category, of course, but to organize large thoughts, categories can’t be beat. All of these works were artistic manipulations of very large landscapes, and that’s good enough to make a category as far as I’m concerned.

Q: More than most art forms, Land Art is subject to the the batterings and erosion of nature. In the book you write about the question of impermanence, which most of these artists have dealt with explicitly in instructions to their descendants or trustees. Do you have a personal preference—preservation or natural decay—or do you approach the question artwork by artwork?

Hogan: For me it breaks down into what the materials of the work are. If you make a work solely out of natural materials—like Spiral Jetty or Double Negative—you are doing a disservice to the laws of the universe if you think it shouldn’t, or won’t, change. But if you incorporate man-made materials—like Lightning Field and its highly polished steel poles—there’s a different assumption about the continuity and permanence of the work. One of the most tragic things to imagine in terms of the works that I saw is an untended future for the Lightning Field, a future in which these stark and lovely sentinels piercing the clear air become rusted, warped, listing sticks. I don’t see an aesthetic point or lesson to that sort of decay in the same way I might expect it from the natural materials that make up Spiral Jetty or Double Negative.

Q: Land Art essentially demands that the viewer see it in person; no reproduction can possibly replicate the whole of that experience. But to a lesser degree, that is true of all one-of-a-kind works of art. Aside from Land Art, are there specific artworks you've traveled to see? Does any one stand out as having affected you more or less powerfully in person than you had expected?

Hogan: Yes, it’s true that virtually all traditional (i.e., painting, sculpture, etc.) forms of art are meant to be seen in person. Most of them were made before it was even possible to see them any other way, through reproductions. I’ve done the usual things—gone to the museums, gone to the cathedrals—to see what people go there to see. On those trips the work that stands out for me is Manet’s Olympia. There’s a tone, a color to that painting that transforms it when you see it in person. It’s impossible to reproduce, and it shifts the painting from a defiant nude into a manifesto on and weird celebration of social sickness. Most of Manet’s works that I’ve seen in person, come to think about it, are very different from their reproductions. There’s a velvety quality to them, a depth and soft opacity that is mesmerizing. I have been more surprised by paintings in person than I have been by cathedrals or other monumental works.

Q: Where was the best place you stayed on the roadtrip? The worst?

Hogan: I admit to special affection for that Motel 6 in Salt Lake City. It wasn’t particularly nice, but it felt like home. And the campground in Moab, which was just fun and adventurous for an apartment dweller like me. The worst? Well, nothing felt particularly dangerous or disgustingly seedy. But I had some low moments in a random motel in St. George, Utah. I had to change rooms three times because every room smelled too much like stale smoke, or mildew, or whatever. I wound up in the handicapped room, which turned out to be filled with bugs because it was rarely used or cleaned. But at that point I had asked to change rooms three times and thought they’d do something horrible to me if I asked again. There were a lot of vacationing families on that trip, and kids played outside in the parking lot—backed up against unhitched trailers—which also sort of depressed me, sitting there in my handicapped room.

Q: Every roadtrip needs a soundtrack. Best music of the trip? Worst?

Hogan: Most of the time I had my iPod on shuffle, and it was amazing how much music “fit” into wherever I was. I could go from Bach to Guns n’ Roses to the Cure to industrial house to Dylan, and it all worked. I guess you can fill physical expansiveness with anything, if you’re in the right mood. I also very specifically remember driving from El Paso to Marfa at night and listening to Josh Rouse’s “1972.” That reverie was broken by a wailing train that seemed to barrel in from nowhere. That’s the musical moment that sticks out. Otherwise it was a lot of miles, a lot of music, and all of it good.

Q: If you could have one of these works in your (imaginary, giant) backyard, which would it be?

Hogan: This may sound strange, especially since I had such a wonderful experience at Lightning Field, but I wouldn’t want any one of them in my (imaginary, giant) backyard. I think the point of these works is to provide visitors with a truly singular experience that somehow becomes absorbed into the brain, treasured and remembered and appearing at odd places in everyday existence. If I had one of these works in my (imaginary, giant) backyard, it wouldn’t offer me a singular experience, seared into my consciousness. Instead it would become yet another part of my landscape that I overlook on a pathetic, daily basis. I’m not proud of it, but I am still in the habit of tuning out—my drive to work, my walk to lunch, my trip to the drycleaners. This trip helped me tune in a bit more, but I still have a long way to go. And until I’m there I want these works to function as they did for me when I took the trip—potent reminders of attentiveness, a break in the daily fold. Maybe I should take up Buddhism.

![]()

Copyright notice: ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press.

Erin Hogan

Spiral Jetta: A Road Trip through the Land Art of the American West

©2008, 190 pages, 26 halftones, 1 map

Cloth $20.00 ISBN: 978-0-226-34845-2 (ISBN-10: 0-226-34845-8)

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Spiral Jetta.

See also:

- Read an excerpt from the book

- Other books in the Culture Trails series

- Our catalog of art titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog