A story from

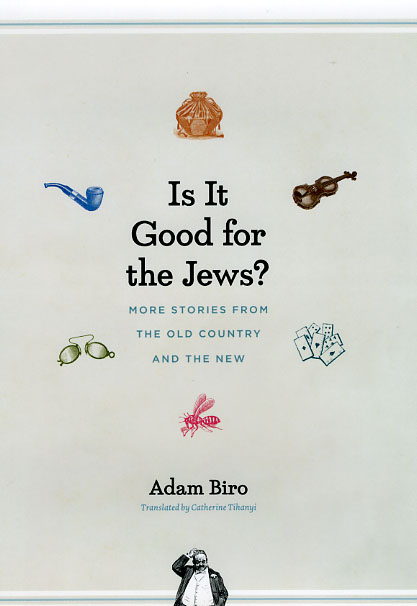

Is It Good for the Jews?

More Stories from the Old Country and the New

Adam Biro

In Praise of Anti-Semites

I am wondering if it wasn’t Doctor Andrée P., who, one day on the phone, first told me the witz that follows. I say witz purposely because my friend Andrée, in spite of her Polish family name, Pi, comes from North Africa and her maiden name is in reality Pe. Yiddish is thus not really her native language, the shtetl isn’t her point of origin, nor can she brag about belonging to the great creative Hollywood family. This hasn’t prevented us from being friends for the last thirty-seven years.

Two Jews are seated a café. Where? Anywhere—the story that follows is universal. You’ll see. So let’s make our life easier and locate it in a place that I’m very familiar with, that you would be interested in knowing if it isn’t already the case, and that I can visualize while telling the story, since it’s where I’m living: Paris, France (warning to readers from Milwaukee, Illinois, or Irvine, California: not to be confused with Paris, Texas, or Paris, Louisiana). I’m speaking here of the City of Lights, that of the Declaration of the Rights of Man (World War II: seventy-five thousand Jews picked up by French police all over France and then deported to the camps by the German… )

On the sidewalk section of a Parisian café, the two Jews are seated in the sun, during this famous and celebrated springtime sun that only Paris can produce. As to Parisian cafés I would tell and retell you about them if it hadn’t been already done and redone and re-redone I am like everybody else, glücklich wie Gott in Frankreich, happy as God in France, happy as a lark, in love with Paris, with the cafés, with lovers.… But you might tell me that the French are anti-Semites, because you’re thinking only of that all the time, even in Paris, you who have the ex-tra-or-dinary luck to live in this city. It’s true, but not for all of them, and they are not just that. And then: they are no more anti-Semitic than, unfortunately I’m assuming, all the other nations in the world. I’m choosing my words carefully here: I do mean all the peoples, without exception. In Japan, where there are no Jews, there is apparently an organization of anti-Semites. There are barely ten thousand Jews left in Poland, which boasts of an anti-Semitic party, anti-Semitic priests, and anti-Semitic ministers of state.

I don’t know if you’re like me (what a hypocritical question, because everywhere and always, you’re only thinking about that): seated as I am in the sun, in a Parisian café, with hopefully a bit a bit of a breeze, I’m already halfway on the road (to happiness, I mean). And, if perchance a friend, and particularly a woman friend, is keeping me company, then there is not much missing for me to say: I was right to come down here (on this earth, I mean).

And yet, our two fellows were not happy. Happiness requires a predisposition for it. Albert Camus used to say that he was gifted at happiness. It’s a gift: you either have it or you don’t. Our two Jews didn’t have it, it was evident; it was engraved on their foreheads. Among other things because they were only thinking about that.

One of them, Moïse Fogelseher, is sipping decaffeinated coffee (it has a chemical taste—but one must be careful with one’s nerves, not to mention insomnia!); the other, Shlomo Talesschmutzer, is enjoying a bottle of Vichy Saint-Yorre water (disgusting—excellent, according to Doctor Zizesbeisser, against uremia, which leads to gout, which, in turn inevitably ends up triggering kidney colic, which, if untreated or not properly treated, lead terrifyingly to death). After swallowing their foul-tasting drinks, they each pull out a newspaper from their pockets. Moïse disappears behind a rag sheet published (undercover, as it is illegal) by the extremest of violently anti-Semitic extreme-right faction. Shlomo is reading Ha’aretz—in Hebrew. They look at each other. Moïse is surprised by what Shlomo is reading.

“What! You’re living in Paris, you speak French, you vote in France, and you’re reading an Israeli daily? I didn’t even know you could read modern Hebrew. I never heard you speak ivrit. Aren’t you a bit snobbish? You don’t even know what is happening around you, in the next street, but you’re interested in Tel-Aviv news.”

“I know only too well what’s happening in the next street. They are burning synagogues, they are drawing swastikas on the walls, so what can I say?”

“They, who?”

“Them. In Ha’aretz, at least I’m reading news about Jews, about people like me.”

“So why are you living here? Why don’t you go live in Israel with people like you? You should be more consistent.”

“I am consistent. I’m French and I live in France. Isn’t this clear? And you, show me what you’re reading. What? I must be hallucinating! You’re reading La France aux Français [France for the French]? Am I seeing right? This rag that I wouldn’t even want to touch with my hands for fear I couldn’t wash out the filth afterward? That’s what you’re reading, you who are reproaching me for reading a Jewish paper? I knew you were a bit meschüge; now I believe that you’ve become totally nuts. I swear you should be locked up!”

Moïse looks calmly at Shlomo, lets him huff, bang on the table, and jump up and down on his seat before answering him: “Not only I’m reading La France aux Français every week, but I have subscribed to it.”

Shlomo jumps up. “I’m leaving. I’ll never see you again. You’re no longer my friend, I don’t ever want to speak to you again. I refuse to be friends with a subscriber to La France aux Français. A paper that wishes for our death, our disappearance, that misses Nazi times, that denies the existence of the gas chambers even while stating that too many Jews came back from the camps. And this is what you’re reading. And besides, you’re giving them money. You know what happened to my family. I don’t wish to remind you of my history. Nor of yours, which you seem to have completely forgotten. Farewell!”

Moïse grabs Shlomo by the sleeve.

“Don’t leave—let me explain.”

“There’s nothing to explain. It’s quite clear. You’ve become insane; you’re dangerous. Unless you’ve become a fascist. It has happened, fascist Jews. You always had weird ideas. You were always weird. I was often warned against you. I was told you were not quite straightforward. I wasn’t listening to gossip. In fact you’re very straightforward. You’re a Nazi. I don’t want to see you again.”

“All right, but before breaking up our friendship forever, listen to me for five minutes. Five, that’s all I’m asking. Five minutes against forever. After that, do what you want.”

Beside himself, Shlomo sits down again. “It’s a mistake to listen to you, but since we’ll never see each other again, I don’t want …”

“OK, show me your Israeli daily. Let’s see the front page. You can read Hebrew but I can’t, so would you please read me the headlines?”

Shlomo grudgingly does as he’s asked. He pulls out the paper from his pocket, carefully unfolds it, and gently with a sort of reverence lays it out on the café table and translates. “Here, on top, is the main headline: ‘16 people dead during an attack against a bus in Jerusalem.’ It’s horrible. Can you imagine, and in the meanwhile, while our people are getting massacred, Monsieur is reading La France aux …”

Moïse interrupts him. “Yes it’s horrible. You need incredibly steady nerves to be able to live there. Every day, or almost every day, there’s an attack. Keep going. Let’s see the other headlines.”

“Down the page a bit: ‘Unemployment went up 3% in Israel. The most recent statistics …’”

Moïse interrupts him again. “No, just the titles. Otherwise we’ll never finish, and before we’re through, you’ll leave forever as you announced. I asked for five minutes, so keep going. Let’s hear the other headlines.”

“Next to this: ‘Israel’s brain drain is increasing. Forty university professors have left for the United States since the beginning of the year.”

Moïse laughs. “Not bad.”

“What do you mean not bad? No, really, I don’t want to have anything to do with you.”

“You promised me five minutes. So read more, on page two.”

“Here the whole page is taken up with an in-depth article dealing with the deterioration of Israel’s image in the world and its consequences for the Jews of the diaspora.”

Moïse laughs again, even more than before. “Excellent, keep going.”

“Anti-Semitic acts are increasing in Europe.”

Moïse: “No comment, and on page three?”

“That’s the page on the economy. You want it?”

“Of course, keep going.”

““Inflation in our country has reached …”

“I’m lapping it up. Keep going. What’s on that page?”

“It’s the sports page. I don’t think you’re interested in it.”

Moïse gesticulates with impatience. “Of course, I’m as interested as can be! I’m interested in everything that has to do with Israel! Of course.”

Shlomo slowly turns the page and reads: “The Maccabees lost 3 to 2 against the Lithuanian team of …”

Moïse can’t stand it anymore. He’s ecstatic. “Against a Lithuanian team. Beaten by the Lithuanians, on top of everything!”

Then suddenly he calms down. He repositions himself comfortably in his bistro chair and says to Shlomo that if he ever had doubts or scruples reading La France aux Français, his scruples have now disappeared and he can see how right he has been. He abruptly opens up his weekly on the table in the place of Ha’aretz, which he sweeps away with the back of his hand, greatly upsetting Shlomo, who rushes to retrieve it and refolds it carefully.

“Okay,” continues Moïse. “Let see. I don’t need to translate, since you read French as well as I do. Since we are both French, from birth even! So, look at the first page, the editorial. Its headline is ‘Jewish France.’ I’ll summarize it for you; I’ve already read it: France is in the hands of the Jews. The president of the republic, the government, the economy, all of the state bureaucracy—in short a monstrous international Jewish conspiracy—is dominating France. Then just pick any headline below and read it.”

Shlomo, disgusted, turns his head away. “I told you you are crazy. You read this and it makes you happy? They have been speaking about this Jewish-Masonic conspiracy for over a century. It’s over a century ago that Drumont’s book was published with the title Jewish France and it provoked scuffles, the breaking of store windows, old people roughed up, hate demonstrations all over France.… And you’re rejoicing! You bastard. I’m calling you a bastard, a fat pig. Forget me. Cross my name and address off your address book and even off your memory.”

“One moment, Just give me one more moment; the five minutes are not over yet. Look at the headlines: ‘Michel Rosenberg just bought our fellow paper Le Clairon du Bas-Lachois.’ And here: ‘We’re learning that the new owner of the movie theaters chain ‘Q-culture’ is called Ariel Baumzweig. No need for comments.’ Then there’s a long article of literary criticism on the last winner of the Anastase prize, Jean Martin. We read in it that one of the great-great grandfathers of this Martin came from Poland and was called Kohn, and this explains his intellectual approach and his style. Can you imagine the time and the energy spent on all this research? Moving on, ‘Behind Bush is the Jewish Texan community which is controlling 30% of Krumply oil company.’ In short, my dear Shlomo, if you read this paper carefully, you’ll discover that we the Jews, we own all the films and movie theaters in the world, all of the good corporations. We are in the background or a part of each government, we’re controlling the Nobel Prize jury, we dominate the academy, we are in charge of publishing and music companies, we are responsible for the bankruptcy of a certain corporation, because it brings us profits, and also of the success of another one for the same reason.… I am reading that we are the kings of the universe, that we are the wealthiest, that we decide war and peace. We have the most beautiful women, everything we touch turns to gold, we are never sick, we live to a very old age, and we succeed at everything—moreover, we are infinitely happy! So I have to tell you, I love this paper. It fills me with happiness and pride to be Jewish. While your newspaper of misfortune, your Ha’aretz, what does it tell us? It writes about unemployment, attacks, deaths, poverty, inflation, brain drain, defeats—and all this happens only to Jews. So, you can understand that if I have to chose between reading one of the two …”

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 14–19 of Is It Good for the Jews?: More Stories from the Old Country and the New by Adam Biro, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2009 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Adam Biro

Is It Good for the Jews?: More Stories from the Old Country and the New

Translated by Catherine Tihanyi

©2009, 152 pages

Cloth $20.00 ISBN: 9780226052175For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Is It Good for the Jews?.

See also:

- An excerpt from Adam Biro’s Two Jews on a Train: Stories from the Old Country and the New

- An excerpt from Adam Biro’s One Must Also Be Hungarian

- Our catalog of books in biography and autobiography

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog